If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

An IBM Case Study: Do Share Buybacks Work?

|

|

Date Published: July 27, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

In 2019, Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty stopped IBM's share buybacks after a twenty-five year run: 1995 through 2019. The IBM 2020 Annual Report states that, "At 2020 year end, we had $2.0 billion remaining in share repurchase authorization." So the share buybacks could resume at a moments notice.

Let's hope not as there are better investments a technology company can make than buying paper.

Let's hope not as there are better investments a technology company can make than buying paper.

IBM Shareholders Have Always Struck Out with Stock Buybacks

- But Share Buybacks Seem so … Logical!

- Three Buyback Failures and an Anomaly Explained

- Stock Buyback #1: Frank T. Cary 1978–79

- Stock Buyback #2: John F. Akers and Louis V. Gerstner 1986–1998

- Stock Buyback #3: Louis V. Gerstner, Samuel J. Palmisano and Virginia M. Rometty 1999–2019

- The Way Forward: Focus on Sales Productivity not Share Buybacks

But Share Buybacks Seem so … Logical!

It is hard to convince shareholders that share buybacks don’t work. The logic just seems so darn rational: reduce the supply of something and demand will drive the price of that something up. One investor on Seeking Alpha, a financial markets forum, commented that “I want to be the last person holding that last share worth $100+ billion dollars!"

Trying to respond to such an individual is reminiscent of what Dale Carnegie wrote decades ago that a man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still. The individual’s comment completely overlooks the demand side of the supply-and-demand equation. The market today doesn’t consider IBM worth much over $140 a share despite its spending $201 billion on its shares since 1995—seventy percent more than its market value at the end of 2021.

Still, some insist that if the corporation buys back enough shares the scarcity will increase shareholder value.

Trying to respond to such an individual is reminiscent of what Dale Carnegie wrote decades ago that a man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still. The individual’s comment completely overlooks the demand side of the supply-and-demand equation. The market today doesn’t consider IBM worth much over $140 a share despite its spending $201 billion on its shares since 1995—seventy percent more than its market value at the end of 2021.

Still, some insist that if the corporation buys back enough shares the scarcity will increase shareholder value.

|

Walt Rostow was the National Security Advisor to President Johnson.

|

In the late 70s, Walt Rostow offered a timeless insight into the current stock buyback phenomenon.

Standing in front of a University of Texas Economics 101 class with several hundred students, he took a single dollar bill out of his wallet, held it up and asked, “How much is this dollar worth?” After all the give-and-take, tongue-in-cheek comments, he proposed that, “If no one has confidence in the government that backs this dollar bill, its only value is as recycled paper and ink.” IBM’s four-decade-long experiment with stock buybacks suggests that as it is with a government and its money, so it is with a business and its stock. |

IBM’s attempts to increase shareholder value through multiple, on-going stock buybacks has proven one undeniable fact: market "trust and confidence" means more to long-term shareholder value than repurchasing any amount of a corporation’s “paper and ink.”

The history of IBM's three stock buybacks (stock repurchases) supports a premise that buybacks will fail the corporation (and its shareholders) during bad times, and, during good times, it appears they add no additional, long-term positive value and, in fact, cause the stock to underperform in the short- and long-terms.

The history of IBM's three stock buybacks (stock repurchases) supports a premise that buybacks will fail the corporation (and its shareholders) during bad times, and, during good times, it appears they add no additional, long-term positive value and, in fact, cause the stock to underperform in the short- and long-terms.

Three Buyback Failures and an Anomaly Explained

On three ever larger and longer occasions, the chief executives of IBM have tried to influence the price of their stock with share buybacks: (1) Cary for two years in 1978 and 1979, (2) Akers-Gerstner for thirteen years from 1986 to 1998, and (3) Gerstner-Palmisano-Rometty for two decades from 1999 to 2018. To determine if shareholder value is actually being generated, Morningstar’s SBBI Large Company Stocks Index is used as a consistent, historical benchmark that spans these periods.

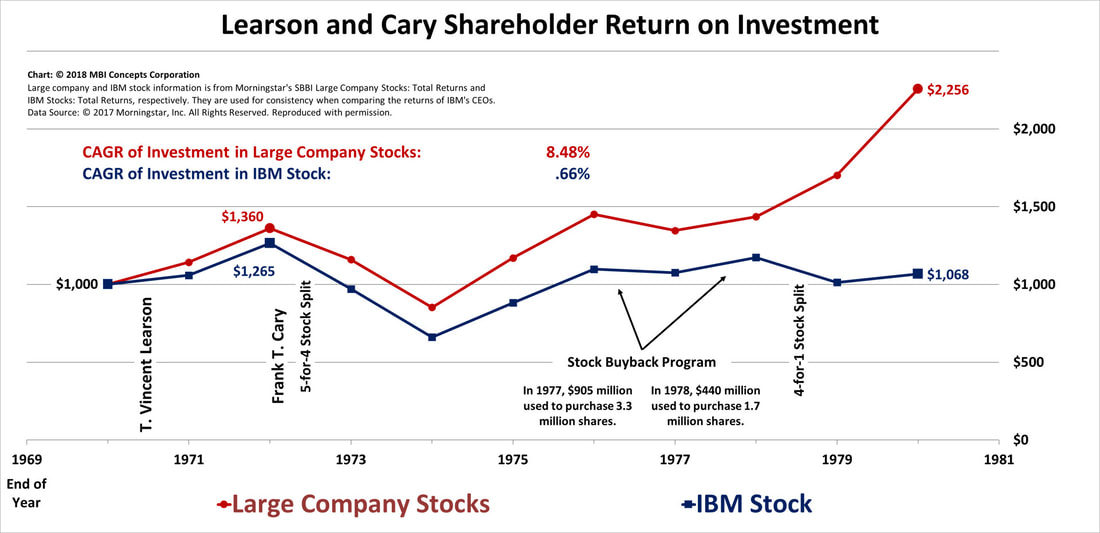

Stock Buyback #1: Frank T. Cary 1978–79

The decade of the seventies was a decade of three Category 5 storms: economic, competitive, and political. Economically, a decade of both high inflation and high unemployment (the combination of which economists previously thought impossible) brought demand to a standstill. Competitively, minicomputers and plug-compatible alternatives threatened the profitability forecasts of the System/370 (the successor of the System/360) and its peripherals. Politically, the success of the mainframe brought an onslaught of government and corporate antitrust suits that spanned the decade.

During such tough times, it is easy to understand why Frank Cary after spending billions to retool manufacturing plants would attempt stock buybacks—for the first time in IBM history—to reward his shareholders. He even tried a 4-for-1 stock split in the hope that lowering the stock price under $100 a share would attract smaller investors.

Unfortunately, as the chart shows below, the returns from the share buybacks only mimicked the benchmark index. If there was any effect, it was minimal and short lived as the benchmark significantly outperformed the corporation’s flat stock performance through 1980.

Unfortunately, as the chart shows below, the returns from the share buybacks only mimicked the benchmark index. If there was any effect, it was minimal and short lived as the benchmark significantly outperformed the corporation’s flat stock performance through 1980.

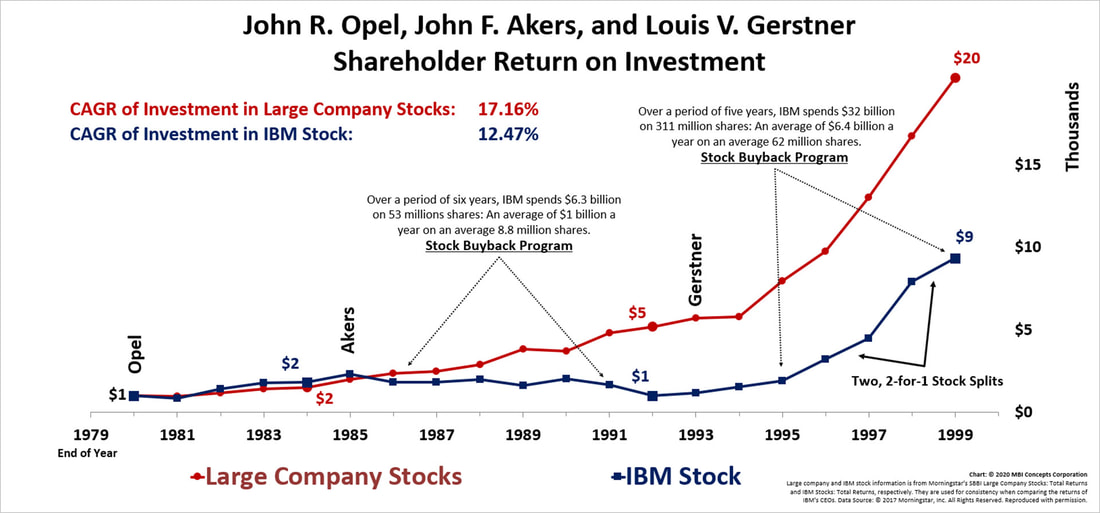

In June 1985, John Akers told analysts that the corporation would not meet the unrealistic growth expectations set by his predecessor: achieving a $100 Billion IBM by 1990 and a $180 Billion IBM by 1994. Even though the Internet did not exist to spread the news, the stock tanked within hours of his meeting and took the market down with it.

But now, because the stock was obviously undervalued, the chief executive started share buybacks.

But now, because the stock was obviously undervalued, the chief executive started share buybacks.

Stock Buyback #2: John F. Akers and Louis V. Gerstner 1986–1998

In IBM’s 1989 Annual Report, John Akers wrote how three years of stock repurchases had enhanced “shareholder value” (the first usage of the term in the corporation’s annual reports). He wrote that the on-going buybacks were “a continuing reflection of the company’s confidence in its prospects, and … its stock as an attractive investment.” Unfortunately, as the chart reflects below, the chief executive’s confidence was misplaced, and the data failed to support his outlook. The market considered the shares overvalued, and shareholder returns fell as the benchmark index, once again, moved significantly upward.

Even the board of directors must have had second thoughts on these share buybacks, because after authorizing $5 billion in repurchases in late 1989, $4.3 billion went unspent. Evidently, they decided to not throw more good money after bad, and it was a wise decision as the company faced several disastrous earnings years.

Even the board of directors must have had second thoughts on these share buybacks, because after authorizing $5 billion in repurchases in late 1989, $4.3 billion went unspent. Evidently, they decided to not throw more good money after bad, and it was a wise decision as the company faced several disastrous earnings years.

But the replacement chief executive, Lou Gerstner, and his board of directors on January 31, 1995 restarted the share buybacks and decided to up the ante. Instead of averaging one billion dollars per year, the chief executive averaged over $6 billion. Did he think his predecessors didn’t reduce the supply of paper enough? Maybe, except that he quadrupled the number of shares in the market with two, 2-for-1 stock splits. Again, this chief executive just like Frank Cary, sent confusing messages to the market. What was the actual strategy for increasing shareholder value: more or less supply? His results though are the only positive anomaly covering four decades of stock manipulation, because it appears that IBM shareholders benefited in the mid-to-late 90s from all this activity.

Realistically, though, Lou Gerstner’s tenure maps directly to the rise of technology stocks and the longest U.S. economic expansion ever measured by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. (NBER). Mr. Gerstner became chief executive three months after the NBER announced the beginning of this record-setting, economic expansion, and he declared his retirement – a bit earlier than analysts expected – two months after the research organization announced the expansion’s end and the start of the first recession in a decade. This isn’t in his book, Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?

After all, it would take a humble chief executive officer to admit that a record-breaking, rising, economic tide had lifted not only his shareholders’ skiffs but all investors’ boats.

And technology stocks still outperformed IBM.

Realistically, though, Lou Gerstner’s tenure maps directly to the rise of technology stocks and the longest U.S. economic expansion ever measured by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. (NBER). Mr. Gerstner became chief executive three months after the NBER announced the beginning of this record-setting, economic expansion, and he declared his retirement – a bit earlier than analysts expected – two months after the research organization announced the expansion’s end and the start of the first recession in a decade. This isn’t in his book, Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?

After all, it would take a humble chief executive officer to admit that a record-breaking, rising, economic tide had lifted not only his shareholders’ skiffs but all investors’ boats.

And technology stocks still outperformed IBM.

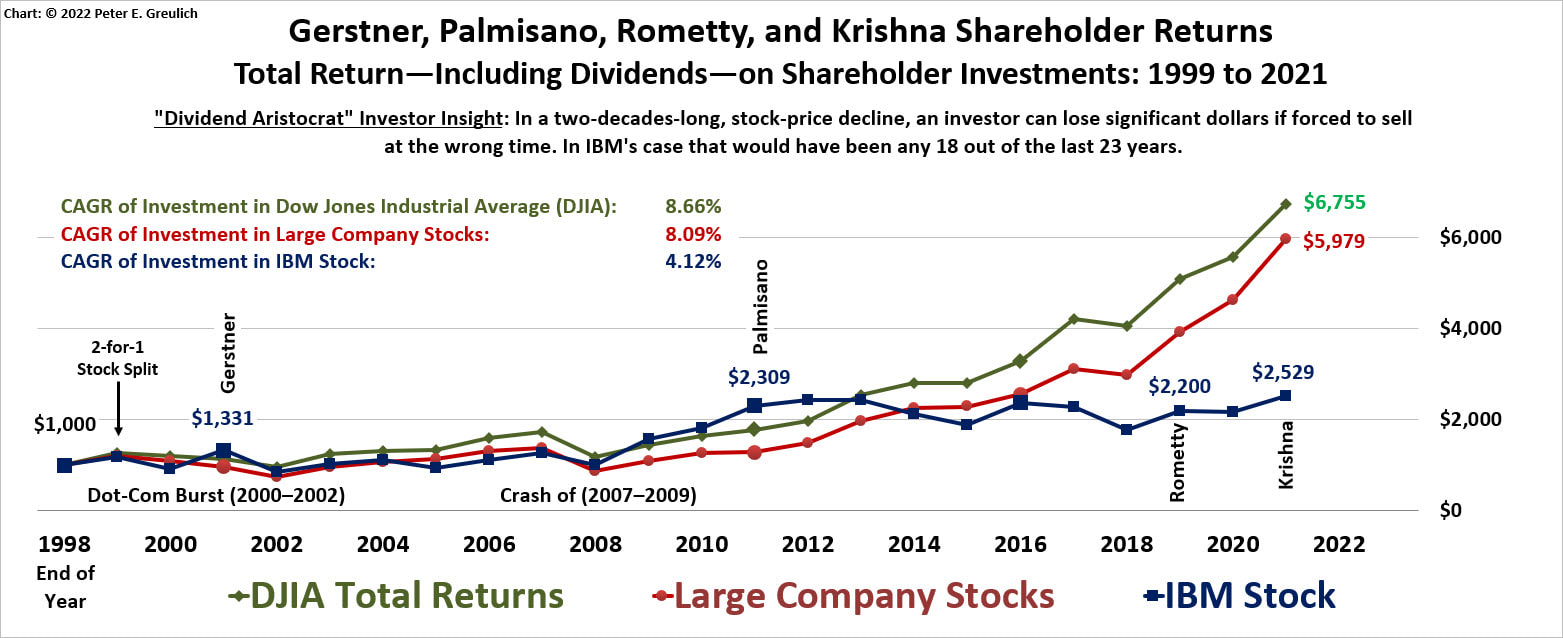

Stock Buyback #3: Louis V. Gerstner, Samuel J. Palmisano and Virginia M. Rometty 1999–2019

Starting in 1999, IBM once again raised the stakes by spending an average $9 billion dollars per year with a peak-year investment in 2007 of almost $19 billion—a twenty year total of $176 billion. These dollars were spent under the premise of increasing shareholder value. Unfortunately for IBM’s shareholders, any investor in a simple index fund that tracked large company stocks has achieved higher returns with significantly less risk. When measured against the Dow Jones Industrial Average, IBM’s long-term shareholders would have ended each year better off in only five out of the last twenty years.

The following chart shows shareholder returns through 2021. IBM cannot avoid the long-term consequences of prioritizing over two decades of investment in paper instead of people, processes and products. So, this chart has been updated to reflect what Arvind Krishna inherited from his predecessors: a hobbled corporation.

The following chart shows shareholder returns through 2021. IBM cannot avoid the long-term consequences of prioritizing over two decades of investment in paper instead of people, processes and products. So, this chart has been updated to reflect what Arvind Krishna inherited from his predecessors: a hobbled corporation.

In its 2020 Annual Report, IBM stated: "We suspended our share repurchase program at the time of the Red Hat closing to focus on debt repayment." Hopefully, this brought to an end one of the worst-performing, longest-term, share buyback schemes in American corporate history.

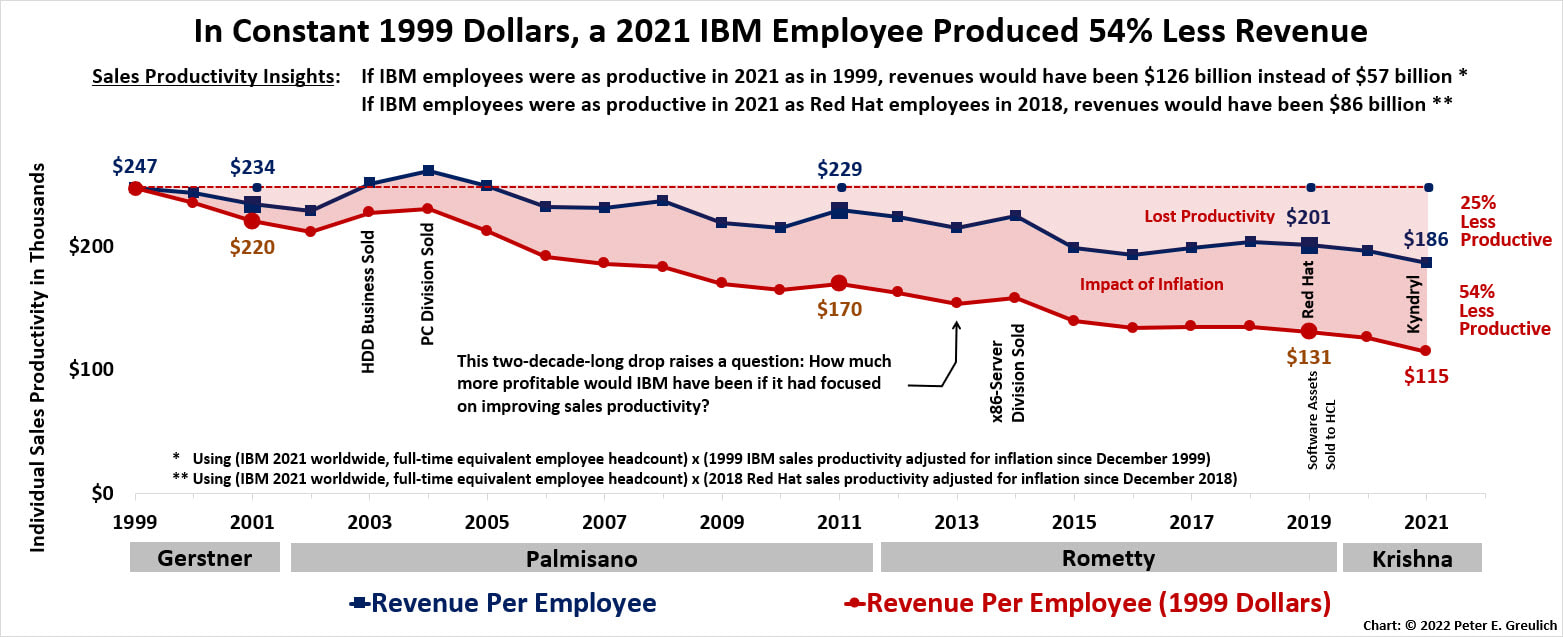

The Way Forward: Focus on Sales Productivity not Share Buybacks

For eight decades, IBM created societal wealth by investing in business-first: people, processes, and products. It drove down costs; it improved quality; it successfully expanded and extended into new markets; and it then distributed its ever-increasing profits equitably with all its stakeholders—who were its stabilizing foundation during tough times. The 21st Century IBM has abandoned this successful formula and its stakeholder foundation is crumbling. One symptom of a company suffering from this insidious form of corporate consumption—an economic wasting disease caused by an obsessive focus on stock buybacks—is falling sales productivity.

As a result, the following chart is the biggest obstacle that Arvind Krishna faces: reversing a two-decade-long free fall in sales productivity.

As a result, the following chart is the biggest obstacle that Arvind Krishna faces: reversing a two-decade-long free fall in sales productivity.

IBM's chief executives have not maintained sales productivity or kept it in line with inflation

Share buybacks have failed IBM’s shareholders three out of three times with one explainable anomaly. Five chief executive officers at one of America’s finest corporations failed in these three attempts to maximize shareholder value.

The corporation’s track record confirms some common-sense notions about stock repurchases:

To maximize long-term profits a business cannot focus on shareholder-first and -foremost, or labor-first and -foremost, or society-first and -foremost. IBM’s history demonstrates that business-first investments are decisions that build and maintain a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem of customers, employees, shareholders and society; and it is the long-term, equitable distribution of business-first profits—considering the economic, social and political environments of the time—that maintains a healthy stakeholder foundation for bad economic times.

A great chief executive officer who can achieve this balance and communicate the why behind his or her decisions is worth their weight in gold. Unfortunately, in these two respects, IBM’s 21st Century chief executives have so far been lightweights. IBM needs a heavyweight leader to survive another century and keep its stock from becoming recycled paper and ink.

It will be seen if Arvind Krishna will learn from his corporation's own history and focus first, on restoring the market’s trust and confidence in the company’s business strategy and then shift the corporation’s priority from investing in paper to people, processes, and products.

This is the way to maximize shareholder value.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

The corporation’s track record confirms some common-sense notions about stock repurchases:

- Stock buybacks that attempt to fix market corrections, fail.

- Stock buybacks can’t compensate for a bad business strategy.

- Stock buybacks, even when done with the best of intentions, still fail.

- Trying to time the market with share repurchases is a gambler’s game not a business man’s.

- Chief executives, with stock compensation plans, are more emotionally and financially vested in their corporate stock than other investors; therefore, their stock buyback decisions should be thoroughly reviewed.

- Stock buyback strategies that cover decades should be called what they are: Corporate dollar-cost averaging—buying a stock, not when it is undervalued, but through all its ups and downs.

- Corporate dollar-cost averaging—such as IBM’s twenty-first-century, two-decade-long share buyback—competes directly with long-term investments that should be making people more productive, products more valuable, and processes more effective.

To maximize long-term profits a business cannot focus on shareholder-first and -foremost, or labor-first and -foremost, or society-first and -foremost. IBM’s history demonstrates that business-first investments are decisions that build and maintain a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem of customers, employees, shareholders and society; and it is the long-term, equitable distribution of business-first profits—considering the economic, social and political environments of the time—that maintains a healthy stakeholder foundation for bad economic times.

A great chief executive officer who can achieve this balance and communicate the why behind his or her decisions is worth their weight in gold. Unfortunately, in these two respects, IBM’s 21st Century chief executives have so far been lightweights. IBM needs a heavyweight leader to survive another century and keep its stock from becoming recycled paper and ink.

It will be seen if Arvind Krishna will learn from his corporation's own history and focus first, on restoring the market’s trust and confidence in the company’s business strategy and then shift the corporation’s priority from investing in paper to people, processes, and products.

This is the way to maximize shareholder value.

Cheers,

- Peter E.