A Review of "True Steel: The Story of George M. Verity"

|

|

Date Published: June 18, 2020

Date Modified: January 9, 2024 |

This is the story of the life of George M. Verity, of the building of an American, industry-leading corporation called American Rolling Mill Company (Armco) and, ultimately, of the human side of the making of steel. But it is a different kind of story—a story of the compassion of one man and his chosen associates for their fellow human beings. As the author, Christy Borth, wrote in his acknowledgements, he found the “Armco Spirit.” It was a “very real and lively force,” and his “sometimes impolite skepticism,” “blunt questions,” and “doubts” were met with open records, and light instead of heat.

In many ways, the record of Armco followed the same path as IBM: massive investments in research and development, a corner office’s trust in his men to deliver—no matter what, investing through recessions when others were pulling back resources, and a tremendous corporate family spirit, all of which were at the foundations of both companies.

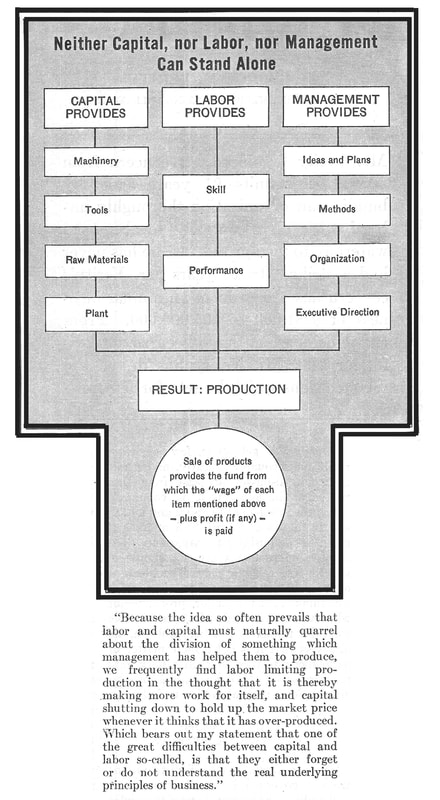

"Our only hope for survival in competition with our large and well-financed competitors, as I see it, lies in our ability to build up a real spirit of cooperation between our management and our men. We cannot afford the wasteful hire‑and‑fire labor policies common to the industry. We must consider our men as co-workers, keep them fully informed of our problems and our policies and provide them with every sound incentive we possibly can.

If we can do these things, we will not only hold our place in the industry but do a better job for our customers than any other mill in the country.”

In many ways, the record of Armco followed the same path as IBM: massive investments in research and development, a corner office’s trust in his men to deliver—no matter what, investing through recessions when others were pulling back resources, and a tremendous corporate family spirit, all of which were at the foundations of both companies.

"Our only hope for survival in competition with our large and well-financed competitors, as I see it, lies in our ability to build up a real spirit of cooperation between our management and our men. We cannot afford the wasteful hire‑and‑fire labor policies common to the industry. We must consider our men as co-workers, keep them fully informed of our problems and our policies and provide them with every sound incentive we possibly can.

If we can do these things, we will not only hold our place in the industry but do a better job for our customers than any other mill in the country.”

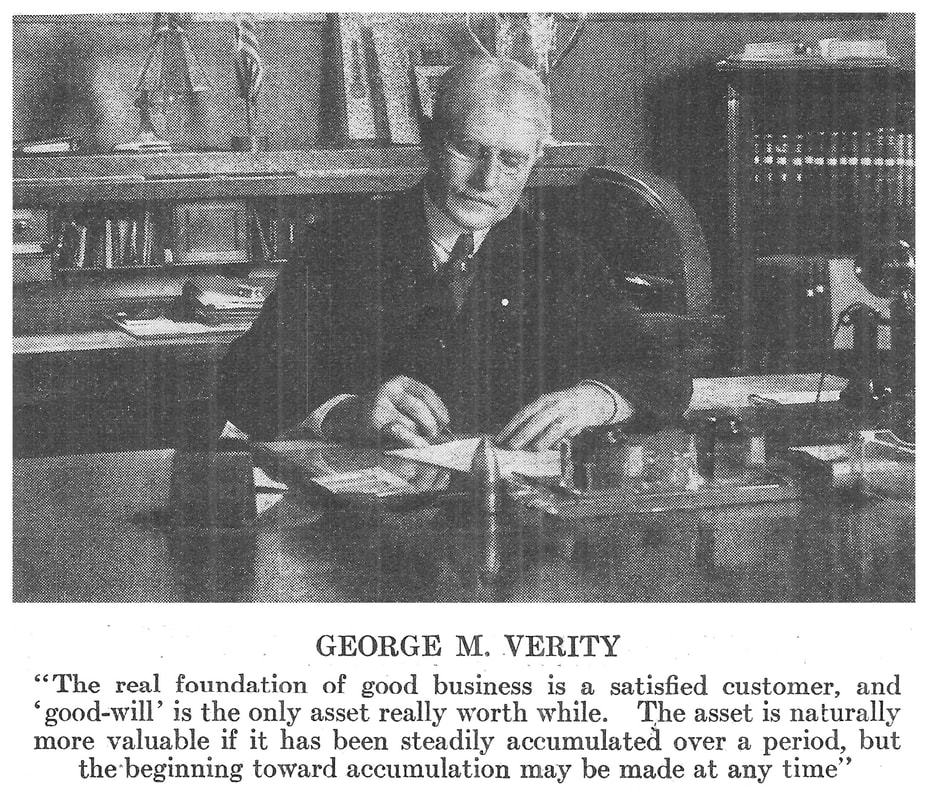

George M. Verity, True Steel: The Story of George M. Verity and his Associates

A Review of "True Steel: The Story of George Matthew Verity and Associates"

- Reviews of the Day: 1941

- Selected Quotes from "True Steel"

- This Author’s Perspective on "True Steel"

Reviews of the Day: 1941

|

“This is the biography of an industrial democracy—the American Rolling Mill Company—and of its creator, George M. Verity, who with his associates not only revolutionized the manufacture and fabrication of sheet steel, but placed employer-employee relations on a new plane of justice, equity, and humanity. … From the top to bottom, the men were given a free hand to make suggestions and improvements. Along with this experimental attitude was carried Verity’s belief that he and his workers were partners. … Armco’s labor policy has been a model of industrial democracy.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 30, 1941

“This is Verity’s story, and no one will deny its epic nature, or the deep humanitarianism of his relations with the men who helped to make the name of Armco great, and the traditions of Middletown a bright torch held high above the murk of bitter injustice that ravaged the ranks of steel labor in the days of the twelve-hour day and the seven-day week.”

Robert L. Perry, The Detroit Free Press, August 31, 1941

|

Reviews Focused on the Humanity of George Verity

“Metallurgically, there may not be such a thing as true steel. Humanly, these associates have demonstrated the long-time wisdom of a policy tempered by truth, justice, service, square, fair and considerate dealing, loyalty and faith toward employees."

The Times Recorder, September 23, 1941

“True Steel is the drama of American enterprise at its courageous best. … One of the most genuinely interesting non-fiction books I’ve read in many months.”

John O. Chappell, Jr., The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 30, 1941

“Men as Mr. Verity have been all too rare in industry. It is well that his life has been chronicled.”

Merab Eberle, The Sunday Journal-Herald Spotlight, September 7, 1941

Selected Quotes from "True Steel"

George M. Verity should speak for himself (and in this case those near him concerning him):

- First, employees speaking of their employer:

|

The wages weren’t so high and the prospects [for the company] didn’t look so good, but a man was treated like a human being instead of a stock pile or a machine, and the president wasn’t too important to stop his buggy and give a guy a lift when he saw him walking to work.

A returning employee after seeking work elsewhere

It wouldn’t be truthful to say there was never any trouble in the mill. There was plenty of it! But it never went beyond the conference table. At that table we learned to look upon Mr. Verity and Charlie Hook as friends rather than as part of any opposition. I never heard Mr. Verity criticized at any labor convention I ever attended, and I attended a lot of them.

Dennis Lauderback, Official of Amalgamated Association of Workers

- Now, a few beliefs and ideas from George Verity

|

Verity's take on "Success and Character"

|

It takes many men of many minds and all sorts of hearts to make up a business world, but of all others give me the man who treats his fellow men with honesty, courtesy and consideration, and I’ll take chances on all his other characteristics.

George Verity

How foolish it is to expect an indifferent workman—a man who looks upon his employer as his enemy—to take an active interest in his employer’s machinery, materials or products! If a man lives in a dirty, unsanitary house, if he is only a day or so ahead of the bill collectors, if he knows that when he dies his widow and children will be helpless, is it unnatural that he should blame his employer? Feeling that way, what real motive has he for being anything but indifferent, if not worse, to his employer’s property and profits.

George M. Verity on the Employer's Responsibility

|

I should be foolish did I even intimate that we have found a ‘golden key’ that will unlock the puzzle of human differences and labor disputes. No such key will ever be discovered, I fancy, until all men are made over. But I can justly say we have found a way of living and working happily together. Our rate of labor turnover is low. Employees are slow to leave us. And we gather together and keep a high quality of men.

George M. Verity on the "Golden Key" to Human Relations

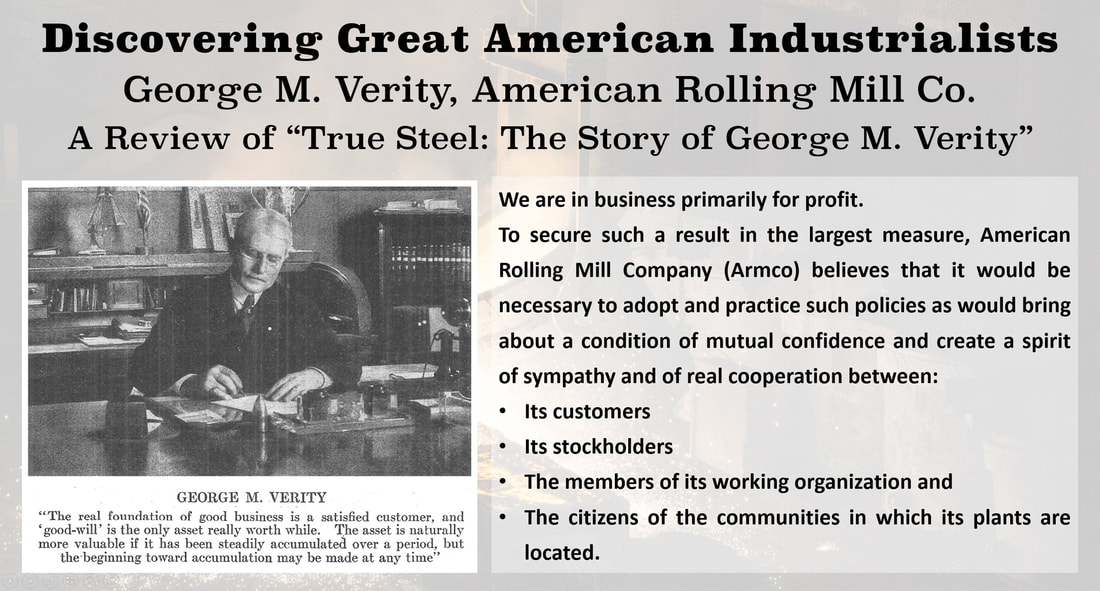

We are in business primarily for profit. To secure such a result in the largest measure, its (Armco) organizers believe that it would be necessary to adopt and practice such policies as would bring about a condition of mutual confidence and create a spirit of sympathy and of real cooperation between the (1) members of its working organization, (2) its customers, (3) its stockholders, and (4) the citizens of the communities in which its plants would be located.

Armco Policies, 1919

To rest is to rust.

George M. Verity

This last quote seems particularly insightful coming from a man made of “true steel" and whose organization developed "rust-less iron."

This seems to be a good thought, upon which, to start the review of this book. |

George Verity chart used to explain relationship between capital and labor

|

This Author's Thoughts and Perceptions

|

The "good will" mentioned here is not the goodwill resulting from an acquisition, but true, valid, customer good will.

|

I particularly appreciated Christy Borth’s comments about the difficult job of research.

In his acknowledgements he thanked those he interviewed, “who tolerated my sometimes impolite skepticism, answered my blunt questions with light when they must have been tempted often to apply heat, and opened records to me when I demanded information or expressed doubts.” How true, and how truly human! Too many times researchers are skeptical of good men and women who carry an admiration for their employers. We worry about the power of personality. This is dispelled with candor, openness and access to information. Borth, in this regard, puts himself on display when he writes, “What is civilization but the task of humanizing humanity.” |

Every author brings their perceptions into their writings, and I appreciated this book because Borth brings to light what was accomplished at Armco: humanizing humanity.

In his research, he found a company and a man who he learned to respect.

In this work he transfers that respect for George M. Verity to me.

In his research, he found a company and a man who he learned to respect.

In this work he transfers that respect for George M. Verity to me.

George M. Verity's Focus on Research and Development, Employees and Community

American Rolling Mill Company (Armco) under George M. Verity had a three-part policy:

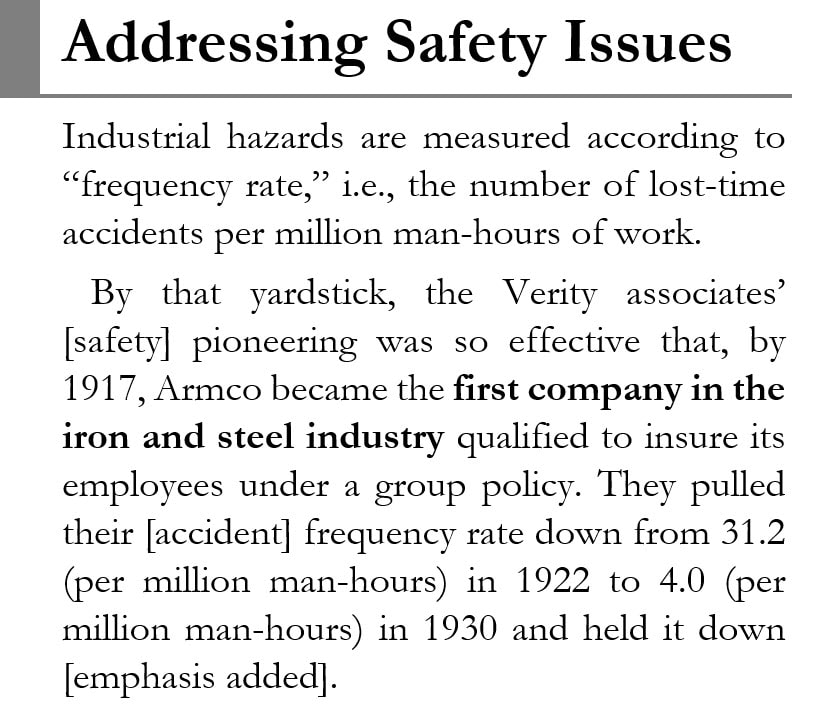

- It believed and invested in technological research. No opportunity was treated as too small if it held out the promise of new technological advances in the steel industry. Suggesting to Armco’s engineers that something that was needed couldn’t be done, like rust-less iron, set its engineers off to prove that it could be done, and the company backed the investments. As a result Armco technicians were responsible for spectacular achievements and the corporation’s constant investment in research and development is one of the consistent themes of this book.

|

There was one insight from 1914 that seems appropriate to highlight this focus on community. Too many believe that early American industrialists didn’t care for their communities, the disadvantaged or the plight of minorities, but many did—especially in the great, memorable corporations of the past.

Many did work for the overall betterment of mankind, and for George M. Verity this included helping blacks as well as Kentucky and Tennessee “hill folk.”

This excerpt from the book proved insightful and memorable:

Many did work for the overall betterment of mankind, and for George M. Verity this included helping blacks as well as Kentucky and Tennessee “hill folk.”

This excerpt from the book proved insightful and memorable:

When the influx of foreign labor was shut off in 1914 [World War I] and negroes came north to fill the gap, the personal service department housed the men until shelter could be provided for their families, and set up schools to overcome their illiteracy and help them become good citizens.

At a cost of $60,000, the company built Booker T. Washington School for their children and presented it to the Middletown Board of Education. In addition, it hired negro social workers, provided playgrounds for the children and sponsored formation of negro clubs.

Similar social work was done to weld into the community the large numbers of Kentucky and Tennessee hill folk attracted to the plant during and after the war.

Particularly fascinating are the tales of early days, before the introduction of labor-saving machinery, when these men, working in blistering temperatures, swathed themselves in wet burlap and tossed strange materials into molten steel as they searched frantically for the ever-elusive “perfect heat.” Sometimes the roof blew off the building; sometimes the molten metal “froze” and had to be chiseled out by hand.

One wants to say that these were “real men.”

One wants to say that these were “real men.”

Comparing Early American Industrialists

- George M. Verity and Henry Ford

George Verity offers a contrast to Henry Ford. Although both men built homes for their employees, cleaned up local communities, provided recreation facilities and wanted what was “best” for their employees, Mr. Verity did not consider it proper to impress his personal views onto the personal lives of his employees because of such corporate sponsored programs, while Henry Ford tried to control the “morality” of his employees.

This was not allowed in a Verity run organization.

This was not allowed in a Verity run organization.

The personal service department does not try to interfere in the lives of the men. It merely applies the Verity doctrine: “People are helped best who help one another most. … You can’t force improvement on people, no matter how necessary or desirable it may be. They will resent it if you try.”

The contrast between the long-term reactions of the employees at Ford and Armco support the wisdom contained in the statement above of George Verity: even though a corporation may invest in changing a worker’s environment to provide an atmosphere for positive change, character improvements must come from within, not without. Individuals must still want to change, otherwise change is opposed.

This is not offered in any way to question the motives of Henry Ford. He, like George M. Verity, was an early pioneer of industrial relations and his personality was much stronger and much, much more published in the press. Although the history of Armco and its growth was attributed to the growth of the automobile industry, I have yet to find anything that would indicate George Verity and Henry Ford ever had a sharing of ideas: they should have.

Speaking humbly of course, I believe that Ford would have been the better for it.

This is not offered in any way to question the motives of Henry Ford. He, like George M. Verity, was an early pioneer of industrial relations and his personality was much stronger and much, much more published in the press. Although the history of Armco and its growth was attributed to the growth of the automobile industry, I have yet to find anything that would indicate George Verity and Henry Ford ever had a sharing of ideas: they should have.

Speaking humbly of course, I believe that Ford would have been the better for it.

- George M. Verity and John H. Patterson

Neither George M. Verity’s nor John H. Patterson’s biographies (or Tom Watson Sr.’s The Lengthening Shadow) connect any dots between these men. Yet, their corporations were almost neighbors (Middletown being approximately 20 miles downstream from Dayton), and each man worked at the same time towards better working conditions for their employees. Probably the most interesting overlap is how they both saved their local communities in the Great Miami River flood of March 1913.

They both saved “their” cities from destruction and invested heavily in the recovery of their communities after the devastating floods in Ohio. Terrible times can bring out the best in humanity and especially in leadership, but these two leaders acted simultaneously at two different points on the same river in the same time showing early America at its best: corporations that understood their dependence upon and responsibility for their communities.

Patterson’s efforts are written in a picturesque manner in The Lengthening Shadow:

They both saved “their” cities from destruction and invested heavily in the recovery of their communities after the devastating floods in Ohio. Terrible times can bring out the best in humanity and especially in leadership, but these two leaders acted simultaneously at two different points on the same river in the same time showing early America at its best: corporations that understood their dependence upon and responsibility for their communities.

Patterson’s efforts are written in a picturesque manner in The Lengthening Shadow:

As the waters slowly began to recede, the dominant structure that came into view was John H. Patterson. … Patterson was behaving magnificently. The factory—its power, heat, electric, and water plants intact—became the center of rescue operations, the ark that was to carry the city through its greatest trial.

Patterson turned over the complete facilities of the NCR to the people of the city, setting his workers to making boats, sending them out to bring people to safety and patrol accessible areas to prevent looting and violence.

Meanwhile twenty miles downstream, George M. Verity and his men were working side-by-side with the people of Middletown. The city was in much more danger as the flood waters came ever closer to the factory’s roaring furnaces. Explosions could have leveled much of the city. Men worked feverishly to prevent this from happening and succeeded but fires broke out—company men died in the effort.

By nightfall, when the oil fires were extinguished and the worst dangers were lessened, the last of the men were ferried to safety on higher ground, leaving on rafts made of planks lashed to empty steel drums. … Since the entire downtown area had been flooded, hundreds of people lacked shelter, dry clothing, food, drinking water and medical attention. Mud, filth and sewage lay ankle-deep upon the streets, sidewalks and the floors of homes and stores, menacing the health of survivors. The stench was nauseating. The water supply was polluted. An epidemic threatened.

Marshaling his [George M. Verity’s] associates, mobilizing all Armco employees and turning out all the company’s railroad dump-cars and construction equipment, he offered the full force of men and machines to the town in the drive to clean up the mess. The company brought in food, clothing and medical supplies, and lent its employees to help police the city against the looting that invariably follows disaster.

“Middletown became a community in the slime left by the flood,” said Harlan (an associate of George Verity’s). “We worked side by side, common laborer rubbing elbows with business executive. Men worked until they reeled with nausea. In that reeking mire we learned to understand one another.”

The disaster had its effect: “It took a flood to wash away our class prejudices.”

After the flood, the community came together in a way it had never done before. A hospital that had been seen as unnecessary before the flood now had the support of the entire city and was built.

A Corporate Pioneer in Advertising

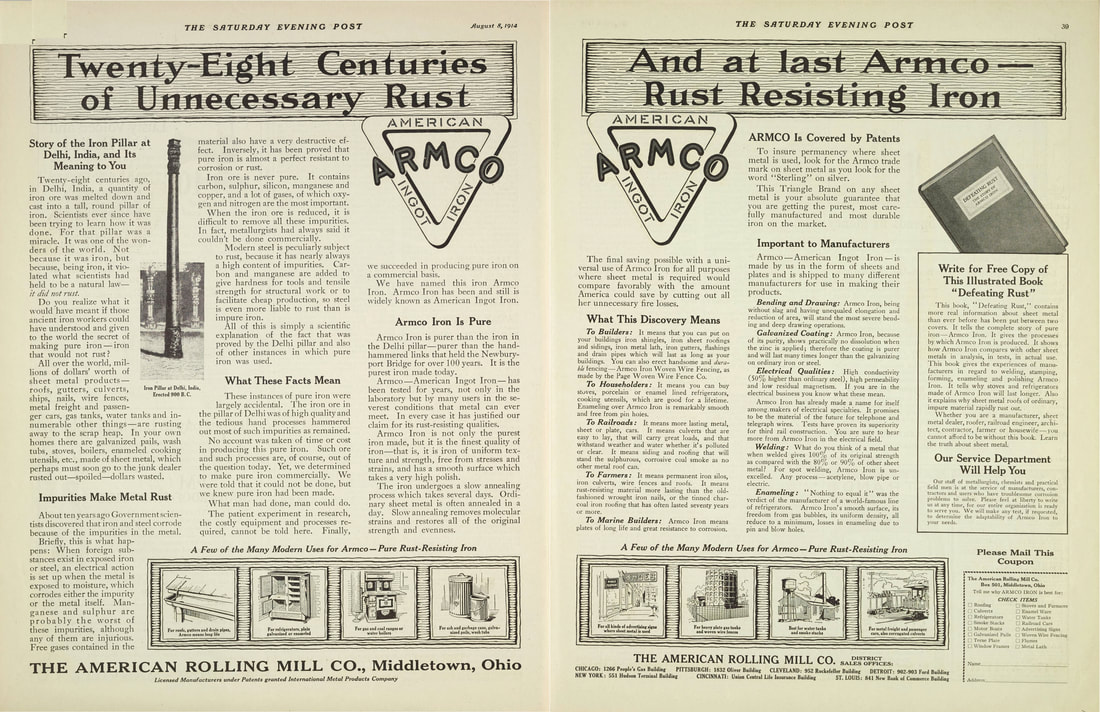

Armco, under the lead of George M. Verity, would become not only an early advertiser, but one of the first companies to advertise a non-consumer product directly to the individual consumer—the home-owner and the housewife. Although their product was only a “base material” in these products, the organization decided they could raise the brand awareness of their product and have consumers ask for it by name: Armco Iron.

They were right. Below is the very first, double-page spread advertisement from a consumer magazine, the Saturday Evening Post from 1914. It showed all the places that a “rust-resisting iron” would improve the standard of living of the individual consumer in gutters, water tanks, containers, trash cans, refrigerators, gas ranges and water boilers.

They were right. Below is the very first, double-page spread advertisement from a consumer magazine, the Saturday Evening Post from 1914. It showed all the places that a “rust-resisting iron” would improve the standard of living of the individual consumer in gutters, water tanks, containers, trash cans, refrigerators, gas ranges and water boilers.

Investing During Down Times and Expecting the Best

In one way, George Verity got his start by investing the way that Tom Watson Sr. did after the Recession of 1920-21. He invested when others were walking away from their industries or closing down their mills. For George Verity it was the Panic of 1897.

He raised capital to get his start and incorporated the American Rolling Mill Company on December 2, 1899. Just like Watson Sr. collected salesmen, George Verity collected the best when they were available.

He raised capital to get his start and incorporated the American Rolling Mill Company on December 2, 1899. Just like Watson Sr. collected salesmen, George Verity collected the best when they were available.

Many men in the industry were then restless with a deep dissatisfaction arising from the widespread mergers and the resultant closing of mills. In every steel-mill town were excellent craftsmen, nursing grouches and ready to leap at a chance to work for an honorable independent employer.

Verity met this need and opportunity by sending a representative to the steel towns to interview men who had lost their jobs through mergers. He offered employment to such men as he felt would best meet the need of the new company. Soon, the industry’s best men, coming from many places, converged on Middletown.

Work for an honorable independent employer? I don't think that has changed in the last 100 years.

Do you?

Cheers,

- Pete

Do you?

Cheers,

- Pete