If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

IBM Failures: Work at Home and Colocation

|

|

Date Published: July 29, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

IBM's sales force had been working from home for most of the 20th Century. Implementing a work-at-home business strategy should not have been a problem for the corporation . . . but flattening and then falling sales productivity indicates that it was.

Why?

Why?

Why IBM Failed in its Implementations of Work at Home and Colocation

- The Imprint of the Financial Mind on IBM

- The Wrong Goal: Cutting Costs Rather than Improving Productivity

- IBM's History of Work at Home

- IBM's Sales Productivity Hits a Wall in 1995

- A Failed Implementation of Work at Home

- A Fact of Capitalism: Productivity Improvements Drive Profits and Benefits

- Did Colocation Improve Employee Productivity

The Imprint of the Financial Mind on IBM

IBM's initial implementation of work at home failed because it was done for the wrong reason: it was a financial strategy intended to maximize the flow of short-term savings to the corporation’s bottom line. Instead, work-at-home should be a productivity strategy that increases an employee’s availability through job flexibility, and improves an employee's performance through increased loyalty.

If IBM had prioritized productivity, greater savings would have flowed to its bottom line over a longer-term.

But IBM’s twenty-first-century strategic decisions have been focused, for more than two decades, on maximizing the saving of a short-term, tangible penny at the expense of long-term, intangible, productivity dollars.

If IBM had prioritized productivity, greater savings would have flowed to its bottom line over a longer-term.

But IBM’s twenty-first-century strategic decisions have been focused, for more than two decades, on maximizing the saving of a short-term, tangible penny at the expense of long-term, intangible, productivity dollars.

The Wrong Goal: Cutting Costs Rather than Improving Productivity

In a layman’s terms, IBM implemented a work-at-home strategy to minimize real estate costs, but the resulting work-at-home implementation—or really, its anarchistic implementation of work at home—negatively impacted employee productivity. To fix the problem, IBM’s twenty-first-century executive leadership believed a new colocation strategy would improve productivity.

So, after twenty years of moving workloads away from its, formerly, highly-productive, highly-motivated and therefore highly-paid employees (workforce rebalancing), it reversed course to move its employees back to the workloads (colocation).

So, after twenty years of moving workloads away from its, formerly, highly-productive, highly-motivated and therefore highly-paid employees (workforce rebalancing), it reversed course to move its employees back to the workloads (colocation).

|

Unfortunately, this didn't work either because the problem at IBM has never been so much who is doing the work and where; but (1) the motivation of the person doing the work, the (2) proper tools to get the job done, and (3) the competence of the person in charge.

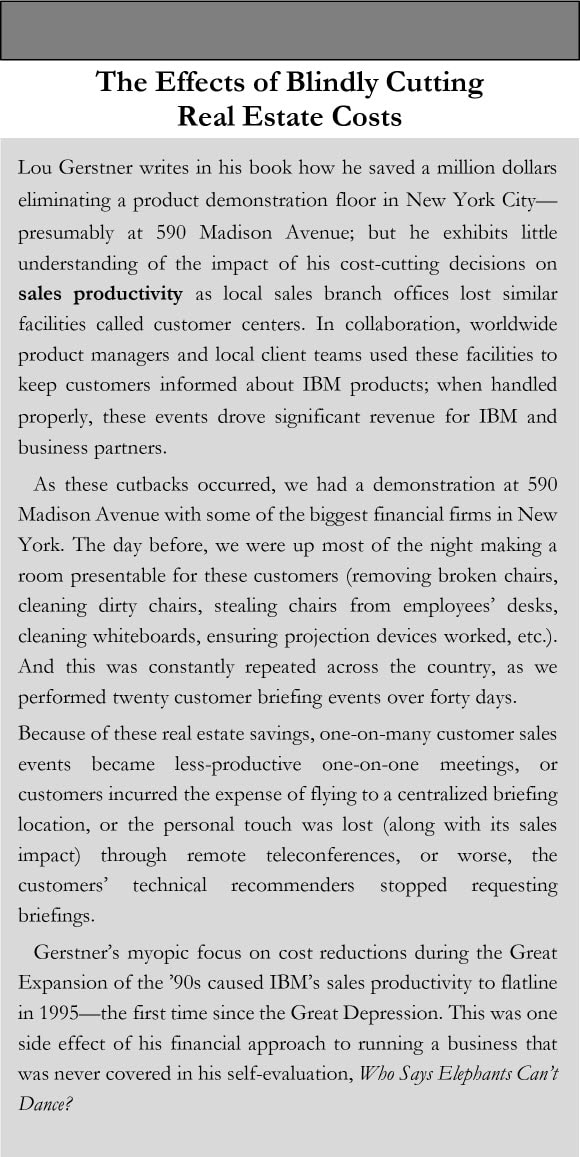

IBM's History of Work at Home In the mid-’90s IBM became a financially controlled corporation. Although financial controls were necessary for a time, many of the continuing reductions negatively impacted the sales force as the corporation stopped making long-term investments to improve employee productivity. The work-at-home movement coincided with the decision to sell off IBM’s massive real estate interests around the world for a quick financial gain (the sidebar captures one instance how these cuts affected the sales productivity of the author and his sales team).

The financial mind is best seen in Louis V. Gerstner’s Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? when he wrote, “From 1994 to 1998, the total savings from these reengineering projects [which included selling IBM’s real estate holdings] was $9.5 billion.” Sales productivity in Mr. Gerstner’s reengineering projects was not a priority (in fact, the word productivity is only used three times in his book and it is never used in the context of improving sales productivity).

|

It is interesting to note that during the same period (1995 to 1998), while he saved $9.5 billion, Lou Gerstner spent $25 billion, or two and one-half times more, on stock repurchases. As he cashed in IBM’s tangible real estate assets to purportedly save the business, he bought paper (share buybacks or share "repurchases" in IBM's annual reports) by the boatload even as IBM’s printing presses churned out stock certificates with two, 2-for-1 stock splits in 1997 and 1999.

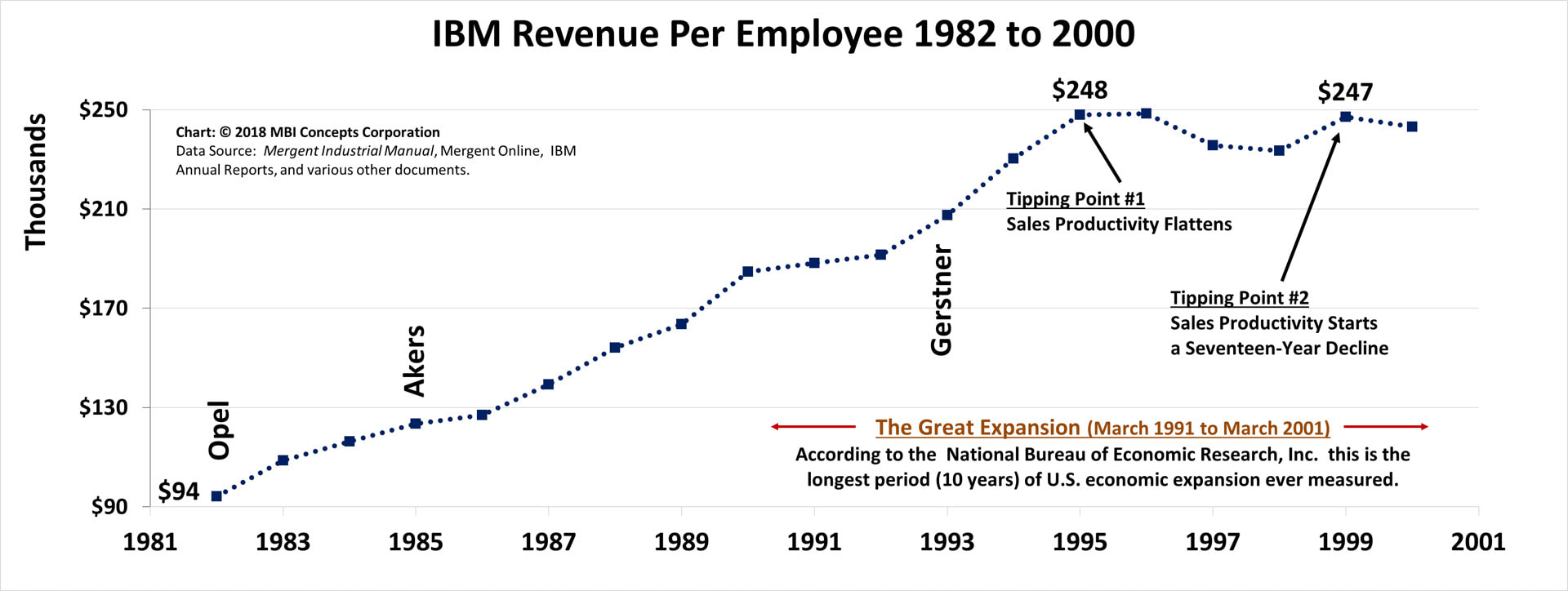

IBM's Sales Productivity Hits a Wall in 1995

After six decades of never-ending productivity growth since the trough of the Great Depression, IBM’s sales productivity flattened in 1995—not during a recession or a depression, but in the middle of the longest economic expansion in U.S. history (A non-economist, like myself, must wonder why there has been a “Great Depression” and a “Great Recession” but this ten-year period of unmatched economic growth isn’t known as the “Great Expansion.”).

As I wrote in THINK Again: The Rometty Edition, there are many reasons why sales productivity hit this wall, but there is one common thread running through all of IBM’s twenty-first-century decisions: its chief executives have maintained a myopic focus on cost savings at the expense of employee productivity.

As I wrote in THINK Again: The Rometty Edition, there are many reasons why sales productivity hit this wall, but there is one common thread running through all of IBM’s twenty-first-century decisions: its chief executives have maintained a myopic focus on cost savings at the expense of employee productivity.

There is no doubt that work at home will be an on-going requirement for most technology corporations. With the growing presence of the women alongside men in decision making roles, the rising requirement for a two-income family to maintain a middle-class standard of living, and the expanding acceptance that couples should share equally in parental responsibilities, this was predetermined years ago.

There is no going back. It is only a question of how work at home should be uniquely implemented within each corporation (within its industry) to maintain, improve or maximize productivity; and it is in the “how” that IBM’s twenty-first-century executives have been getting most everything wrong for the last two decades.

There is no going back. It is only a question of how work at home should be uniquely implemented within each corporation (within its industry) to maintain, improve or maximize productivity; and it is in the “how” that IBM’s twenty-first-century executives have been getting most everything wrong for the last two decades.

A Failed Implementation of Work at Home

IBM’s work-at-home implementation was anarchistic—it was every man and woman for themselves. Once the real estate cost savings were realized, interest was lost in funding work-at-home as a strategy to improve productivity. The local management teams were not offered the opportunity to determine where, how, or the degree to which work at home should be implemented; (1) there was little discussion with first-line managers on how to maintain close working relationships with and between their now-remote employees; (2) some managers who were fully competent with a face-to-face workforce failed utterly at maintaining long-distance relationships—these relationships are more difficult to maintain; (3) there was no discussion of how to replace IBM’s lost face-to-face sales and technical-sales mentoring system for new employees; and (4) there was no input taken on how to enhance IBM’s leading-edge, quality sales and management education for the work-at-home environment.

Little of the $9.5 billion dollars in savings found its way back to the first-line management teams for local team building, or local sales and technical education events, as any savings was siphoned off to fund stock buybacks, not improve productivity. Such implementations would have required a tangible investment of dollars. And the reengineering “cuts” continued everywhere including back-end sales support, back-end technical-sales support, and front-line sales applications: many commented during this time, “At least after I hit ‘Enter,’ I can now relax with a cup of coffee in the comfort of my home waiting on the application to respond.”

Non-production is unproductive whether it is at home or in the office, but in the home office it is dangerously opaque. Ineffectual work-at-home processes, if not tracked closely, may only reveal their positive or negative effects on a corporation’s bottom line after many years; therefore, an accurate analysis of Lou Gerstner’s reengineering projects requires the perspective of decades to evaluate their long-term impact.

Even then, work at home was only one failed implementation of many that has destroyed decades of employee productivity.

Colocation failed too.

Little of the $9.5 billion dollars in savings found its way back to the first-line management teams for local team building, or local sales and technical education events, as any savings was siphoned off to fund stock buybacks, not improve productivity. Such implementations would have required a tangible investment of dollars. And the reengineering “cuts” continued everywhere including back-end sales support, back-end technical-sales support, and front-line sales applications: many commented during this time, “At least after I hit ‘Enter,’ I can now relax with a cup of coffee in the comfort of my home waiting on the application to respond.”

Non-production is unproductive whether it is at home or in the office, but in the home office it is dangerously opaque. Ineffectual work-at-home processes, if not tracked closely, may only reveal their positive or negative effects on a corporation’s bottom line after many years; therefore, an accurate analysis of Lou Gerstner’s reengineering projects requires the perspective of decades to evaluate their long-term impact.

Even then, work at home was only one failed implementation of many that has destroyed decades of employee productivity.

Colocation failed too.

Did Colocation Improve Employee Productivity?

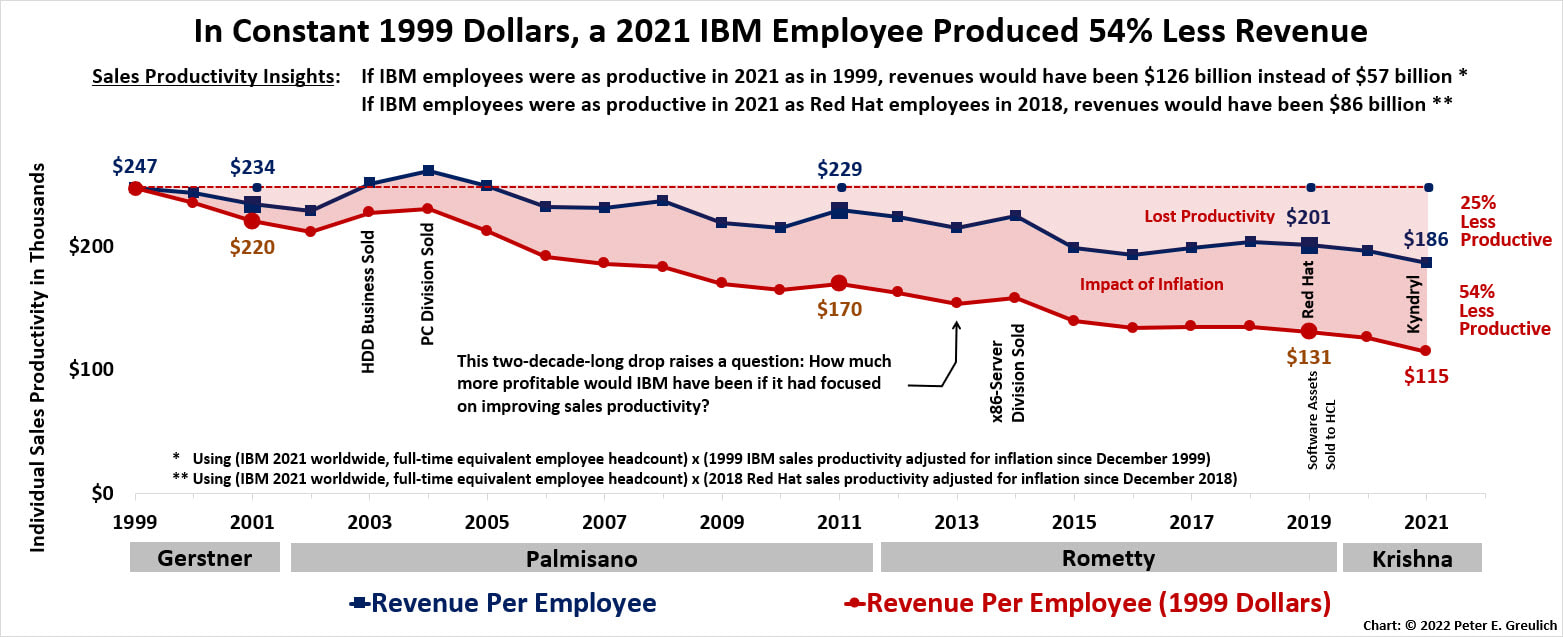

This chart answers the question. In relation to inflation, whether it is work at home or colocation (2017–19 timeframe) both strategies have contributed to an overall fall in sales productivity in the twenty-first century.

IBM’s executive decision to reverse this work-at-home strategy—called colocation—faced the same hurdles as work at home because it was hindered by the same wrong-headed financial motivations. Both implementations are emblematic of the biggest problem the corporation exhibits in this century: it has lost sight of the fact that an enthusiastic, engaged and passionate employee is a productive employee.

IBM’s CFOs gambled that individuals would leave IBM rather than leave their families and homes. From talking with some of the employees—friends—who left the corporation, the financial minds were right. This enabled the financial team to show Wall Street further quarters of rising earnings per share by again lowering labor costs. Unfortunately, earnings once again came at expense of sales productivity because many employees refused to move. Colocation further weakened IBM’s once-deep bench of sales and technical expertise in front of the customer, and transfered more of its sales and technical knowledge to business partners and competitors.

Colocation brought the remaining balance of the employees—that are not the source of the problem—intimately closer to those who are the source of the problem: executives who don’t understand that an enthusiastic employee is a productive employee.

Work at home, when properly implemented, can cut costs and improve productivity but it depends to a great degree on the self-discipline and motivation of the individual. Although a business is not responsible for an individual’s motivation, it is responsible for: (1) maintaining a work environment that encourages, not discourages, enthusiasm; (2) hiring individuals who are inherently self-motivated; (3) and retaining those individuals by recognizing and rewarding performance. This demands a first-rate, first-line management team that is empowered to reinforce that performance matters.

Unfortunately, both work at home and colocation were just financially-driven, cost-reduction strategies that invited further negative consequences for a corporation that could not afford to see its sales productivity drop further, since it had already been dropping—almost nonstop—for two decades.

IBM’s CFOs gambled that individuals would leave IBM rather than leave their families and homes. From talking with some of the employees—friends—who left the corporation, the financial minds were right. This enabled the financial team to show Wall Street further quarters of rising earnings per share by again lowering labor costs. Unfortunately, earnings once again came at expense of sales productivity because many employees refused to move. Colocation further weakened IBM’s once-deep bench of sales and technical expertise in front of the customer, and transfered more of its sales and technical knowledge to business partners and competitors.

Colocation brought the remaining balance of the employees—that are not the source of the problem—intimately closer to those who are the source of the problem: executives who don’t understand that an enthusiastic employee is a productive employee.

Work at home, when properly implemented, can cut costs and improve productivity but it depends to a great degree on the self-discipline and motivation of the individual. Although a business is not responsible for an individual’s motivation, it is responsible for: (1) maintaining a work environment that encourages, not discourages, enthusiasm; (2) hiring individuals who are inherently self-motivated; (3) and retaining those individuals by recognizing and rewarding performance. This demands a first-rate, first-line management team that is empowered to reinforce that performance matters.

Unfortunately, both work at home and colocation were just financially-driven, cost-reduction strategies that invited further negative consequences for a corporation that could not afford to see its sales productivity drop further, since it had already been dropping—almost nonstop—for two decades.

A Fact of Capitalism: Productivity Improvements Drive Profits and Benefits

Today, many business analysts (and even IBM employees) believe that it was a twentieth-century monopoly position that allowed IBM to provide generous employee benefits. The anecdote has been repeated so often as to be accepted as fact. In fact, IBM was constantly in competitive battles; but, especially during the ’70s, the company faced three simultaneous Category 5 storms: (1) on the competitive front from minicomputers and plug-compatible peripherals, (2) on the economic front from stagflation, and (3) on the political and legal fronts from a plethora of monopoly lawsuits. [These are covered in-depth in THINK Again: The Rometty Edition.]

|

Instead of depending on a monopoly position, IBM’s leadership invested in modernizing its plants, and making its employees more productive, processes more effective, and products more valuable. It was the return on these investments by Frank T. Cary, not a market monopoly, that simultaneously maintained leading-edge employee benefits and shareholder returns.

It seems that too many twenty-first-century employers (and employees) have forgotten the lesson that so many early twentieth-century industrialists learned. |

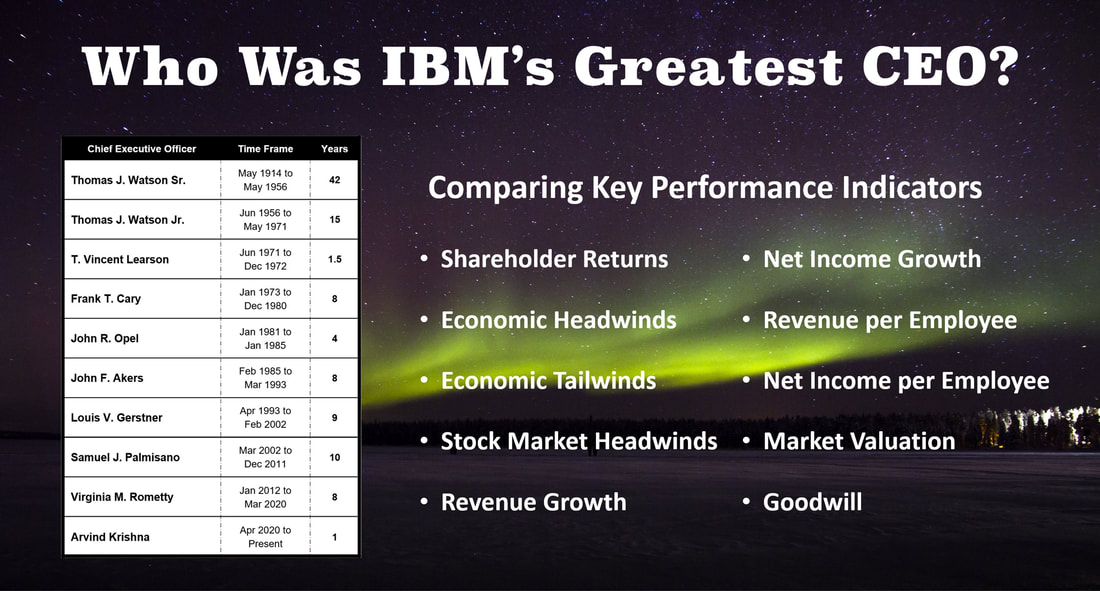

Read and compare the records of IBM's CEOs.

|

Revenue growth comes from management’s ability to improve production—lower costs, improve quality and achieve higher employee productivity. Employee benefits are not available for the asking. They must be earned or justified through a return on investment analysis and macro-level productivity improvements. And, yes, this is as much a management responsibility as it is the individual employees'. It takes a team effort.

Work at home, properly implemented by industry, does withstand the rigors of an investment analysis. In the technology industry, work at home should have paid productivity and shareholder dividends for IBM.

Work at home didn’t fail IBM; IBM failed in its implementation of work at home.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

Work at home, properly implemented by industry, does withstand the rigors of an investment analysis. In the technology industry, work at home should have paid productivity and shareholder dividends for IBM.

Work at home didn’t fail IBM; IBM failed in its implementation of work at home.

Cheers,

- Peter E.