"William Guggenheim: The Story of an Adventurous Career" by Gatenby Williams

- Reviews of the Day: 1934

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

Reviews of the Day: 1934

|

"Written in the manner of a novel, but not fictionalized, it is an entertaining and interesting account of the economic problems of the times and an unusual record of the colorful, tragic, and amusing life of one of America's most famous families."

The Cincinnati Enquirer, February 1934

"One of the best of recent biographies. . . . In it is told the story of how members of a Philadelphia firm of embroidery importers attained domination over the mineral wealth of two continents."

The Pittsburgh Press, News and Reviews, February 1934

|

This Author's Thoughts and Perceptions

This is an autobiography of William Guggenheim written by the industrialist and capitalist under the pseudonym of Gatenby Williams. The “author” does not reveal this fact. The reader should therefore be more than a little apprehensive as the author describes himself in sometimes superlative terms without many supportive facts. Personal memories, even without any self-serving or self-indulgent motivations, are subject to the vagaries of time. Personal observations need third-party validation. In this work of non-fiction, the reader at times expects Mr. Guggenheim to leap tall buildings in a single bound.

William Guggenheim’s—aka Gatenby Williams’—success may have been the result of hard work, but his story is not a rags-to-riches Horatio Alger story. It is more along the lines of Horatio Alger’s son played by William using his father’s (Meyer Guggenheim’s) riches to become even more wealthy. Of course, there is nothing wrong with this, as long as the individual understands the powerful, supporting hand they were dealt in the game of life.

I am not convinced after reading this autobiography that William Guggenheim understood the winning hand he was dealt as humble and empathetic are two words I would not use to describe him.

William Guggenheim’s—aka Gatenby Williams’—success may have been the result of hard work, but his story is not a rags-to-riches Horatio Alger story. It is more along the lines of Horatio Alger’s son played by William using his father’s (Meyer Guggenheim’s) riches to become even more wealthy. Of course, there is nothing wrong with this, as long as the individual understands the powerful, supporting hand they were dealt in the game of life.

I am not convinced after reading this autobiography that William Guggenheim understood the winning hand he was dealt as humble and empathetic are two words I would not use to describe him.

Why I read this book

I read this work because of my on-going research on Watson Sr. This was a truly tangential read. I found the book quite uninteresting. When I start a book, I usually finish it. I have found in almost every book I have ever read, that no matter how dull or divergent the path, one chapter can usually be dog-eared that makes a book worth the effort. This book failed to even meet this minimal criteria.

Maybe one day, as I reflect back on all the biographies of America’s greatest business leaders, industrialists and capitalists, I will find a categorization for this book. Right now, I am at a loss but at least the book contained the one paragraph that satisfied the reason I bought it.

Maybe one day, as I reflect back on all the biographies of America’s greatest business leaders, industrialists and capitalists, I will find a categorization for this book. Right now, I am at a loss but at least the book contained the one paragraph that satisfied the reason I bought it.

|

The Two Men Who Very Publicly Returned their "Fascist" Medals |

|

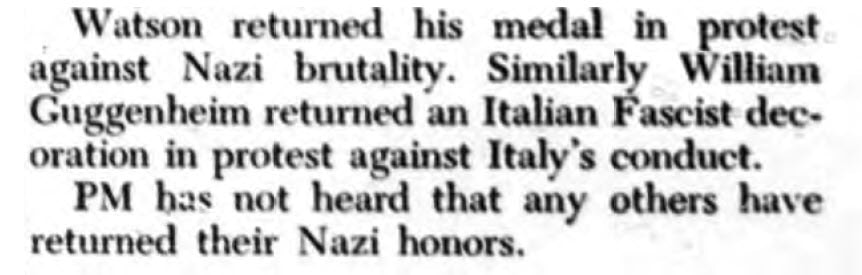

In 1937, Thomas J. Watson Sr. and F. H. Fentener van Vlissingen were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross of the Order of the German Eagle as the incoming and outgoing presidents of the International Chamber of Commerce by Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, president of the Reichsbank. In 1940 Watson very publicly returned his medal. I wondered if anyone else had returned their medals from the fascists leadership composed of Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito and Stalin?

|

New York PM Daily. August 9, 1940

|

Medals were given away quite liberally by this foursome and, sometimes, with much notoriety. The presentation of the German Medal to Henry Ford at his 75th birthday party in Detroit was unexpected. He made no formal response at the time other than to accept the medal. Charles Lindbergh was also handed his medal unexpectedly by Goering at an informal gathering at the American Embassy.

Scott Berg in Lindbergh wrote that Mr. Lindbergh was surprised and accepted the decoration “as unceremoniously as it had been presented.” It would seem that part of the modus operandi of handing out these medals was to surprise the “victim.” Of course, the Ford and Lindbergh medals were never returned. So far, only one other person than Watson appears to have publicly returned a fascist award. This was William Guggenheim. [See Footnote #1]

The returning of his medal was noted in the press of the day as Mr. Guggenheim stated that the declaration of “war by Italy against the democracies of Great Britain and France was a profound shock to me. Not only will Christianity suffer, but every civilized human, regardless of creed.” The press noted in August 1940 that besides Watson and Guggenheim they “had not heard that any others have returned their … honors.” Although most individuals probably threw their fascist medals into the nearest dumpster, according to the press, only two returned them with enough fanfare to drive publicity over the event.

In this book, William Guggenheim describes the circumstances surrounding the presentation of his award. The medal he received wasn’t from Germany it was from Italy. And it wasn’t awarded during a time of Italian fascism but rather two decades earlier, in 1920, after the end of World War I by a grateful Italian government to recognize “his [William Guggenheim’s] patriotic services … wherein he had been such a stanch supporter of the Allies.” In response, Mr. Guggenheim “reaffirmed” his friendship with the then United States ally and praised her part in World War I.

Tom Watson returned his German medal on June 6, 1940. On June 10, Italy officially entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers by declaring war on France and Great Britain. One day later, on June 11, William Guggenheim announced he was returning his medal.

The book review above stands but the necessary tidbit of information surrounding the medal was uncovered in his work. I won’t be going back, though, to read this book a second time. This is about as critical as I care to be about the work of any author.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

Scott Berg in Lindbergh wrote that Mr. Lindbergh was surprised and accepted the decoration “as unceremoniously as it had been presented.” It would seem that part of the modus operandi of handing out these medals was to surprise the “victim.” Of course, the Ford and Lindbergh medals were never returned. So far, only one other person than Watson appears to have publicly returned a fascist award. This was William Guggenheim. [See Footnote #1]

The returning of his medal was noted in the press of the day as Mr. Guggenheim stated that the declaration of “war by Italy against the democracies of Great Britain and France was a profound shock to me. Not only will Christianity suffer, but every civilized human, regardless of creed.” The press noted in August 1940 that besides Watson and Guggenheim they “had not heard that any others have returned their … honors.” Although most individuals probably threw their fascist medals into the nearest dumpster, according to the press, only two returned them with enough fanfare to drive publicity over the event.

In this book, William Guggenheim describes the circumstances surrounding the presentation of his award. The medal he received wasn’t from Germany it was from Italy. And it wasn’t awarded during a time of Italian fascism but rather two decades earlier, in 1920, after the end of World War I by a grateful Italian government to recognize “his [William Guggenheim’s] patriotic services … wherein he had been such a stanch supporter of the Allies.” In response, Mr. Guggenheim “reaffirmed” his friendship with the then United States ally and praised her part in World War I.

Tom Watson returned his German medal on June 6, 1940. On June 10, Italy officially entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers by declaring war on France and Great Britain. One day later, on June 11, William Guggenheim announced he was returning his medal.

The book review above stands but the necessary tidbit of information surrounding the medal was uncovered in his work. I won’t be going back, though, to read this book a second time. This is about as critical as I care to be about the work of any author.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

Footnote #1: A Scott Berg also wrote that the press of the day, “which had grown to resent Lindbergh’s uncooperative attitude, instantly revised history. In December, for example, Liberty Magazine reported Lindbergh’s having flown to Berlin especially to receive the medal; The New York Times wrote of his proudly wearing the medal 'all evening,' when it had been left unceremoniously in the box it was presented in."