Capitalism Needs Industrialist-Minded CEOs

|

|

Date Published: June 9, 2021

Date Modified: October 18, 2023 |

The purpose of this article is to make the words "capitalist" and "industrialist" be born again and live for the reader.

May these words smile as the reader understands their true meanings within the context of American history.

Words like people have gender: some are masculine, some feminine, others neuter. English is one of the few languages which does not make a differentiation; but even in English we sometimes give a definite gender to things, as: "Look at that ship isn't she beautiful?" This animism of languages [The belief that objects have souls that may exist apart from their material bodies.] does not stop at genders!

Words may also be hurt or be sad, as when they are mutilated . . . or when their meanings are used incorrectly; but they smile when we use them correctly and with elegance.

When we look up the meaning of a new word, that word comes to life that day for us. It is born and it lives.

Ferdinando D. Marino, "The Tragedy of Words," 1947

Capitalism Needs Industrialist-Minded Chief Executive Officers

- What is the Difference between a Capitalist and an Industrialist?

- Here a Capitalist, there a Capitalist, everywhere a Capitalist - Capitalist

- Capitalism’s Foundation is a Strong Stakeholder Ecosystem

- The Author’s Perspective

What is the Difference between a Capitalist and an Industrialist?

|

If anyone had used the term “capitalist” in reference to Henry Ford of Ford Motor Company, Tom Watson Sr. of IBM, Harvey S. Firestone of Firestone Tire Company, Alfred P. Sloan of General Motors, Elbert H. Gary of U.S. Steel Corporation, Edward A Filene of the William Filene’s Sons Company, George F. Johnson of Endicott Johnson Company, William C. Procter of Procter & Gamble, or Charles A. Coffin, Gerard Swope and Owen D. Young of General Electric, one of these men would have been offended to the point of apoplexy, most would have wondered at the individual’s ignorant usage of the term, but all of them would have quickly corrected the person with a simple statement:

" I am not a capitalist. I'm an industrialist. I am building something to last.” The long-term business goal of industrialists was at times as different from a capitalist’s as an architect’s vision could be from a developer’s in the design of a residential skyscraper: Is maximum long-term profits found in designing a superlative living environment or for maximum occupancy per square foot? |

Yet, without a doubt, the majority of Americans think of these men as exemplary "capitalists." Although exemplary, they did not think of themselves as capitalists – far from it.

These individuals preferred the term and classification of "industrialist." Even though they are no longer around to guide today’s leaders, their spirit and their insights live in their biographies, autobiographies, speeches and press interviews. Even as their words have become more electronically accessible, their thoughts are the internet equivalent of little-referenced manuscripts gathering dust on a bookshelf [Here are a few recommended industrialist biographies with reviews].

These individuals preferred the term and classification of "industrialist." Even though they are no longer around to guide today’s leaders, their spirit and their insights live in their biographies, autobiographies, speeches and press interviews. Even as their words have become more electronically accessible, their thoughts are the internet equivalent of little-referenced manuscripts gathering dust on a bookshelf [Here are a few recommended industrialist biographies with reviews].

Industrialists within a System of Capitalism

Much of the fallacy of thought concerning industrialists and capitalists is hidden in the evolving definition of the word capitalist. The word’s meaning has been extended, and these new extensions have been applied retroactively to these individuals. Today, capitalist is used in at least three ways: (1) a person who has capital invested in business enterprises—usually an extensive amount of capital, (2) a very wealthy person or (3) an advocate of capitalism.

Let’s deal with these in reverse order.

Capitalists love capitalism but being an advocate of capitalism, in the past, did not make a person a capitalist. These industrialists were all proponents of the economic system of capitalism but did not consider themselves capitalists. Secondly, capitalists in the early 20th Century were wealthier than the masses. The wealthy had cash in enough abundance to fund growing businesses, but to these early business founders, a wealthy person was not necessarily a capitalist—one who provides investment capital. Although when they desperately needed funds, they probably wished that every wealthy person was a capitalist.

Let’s deal with these in reverse order.

Capitalists love capitalism but being an advocate of capitalism, in the past, did not make a person a capitalist. These industrialists were all proponents of the economic system of capitalism but did not consider themselves capitalists. Secondly, capitalists in the early 20th Century were wealthier than the masses. The wealthy had cash in enough abundance to fund growing businesses, but to these early business founders, a wealthy person was not necessarily a capitalist—one who provides investment capital. Although when they desperately needed funds, they probably wished that every wealthy person was a capitalist.

|

America’s economic forefathers restricted their definition of capitalists to the first of these three definitions. Capitalists were individuals who invested money—usually significant amounts of money—in business enterprises. “Capitalists,” one of these industrialists said facetiously, “are individuals who put their money to work so they don’t have to.”

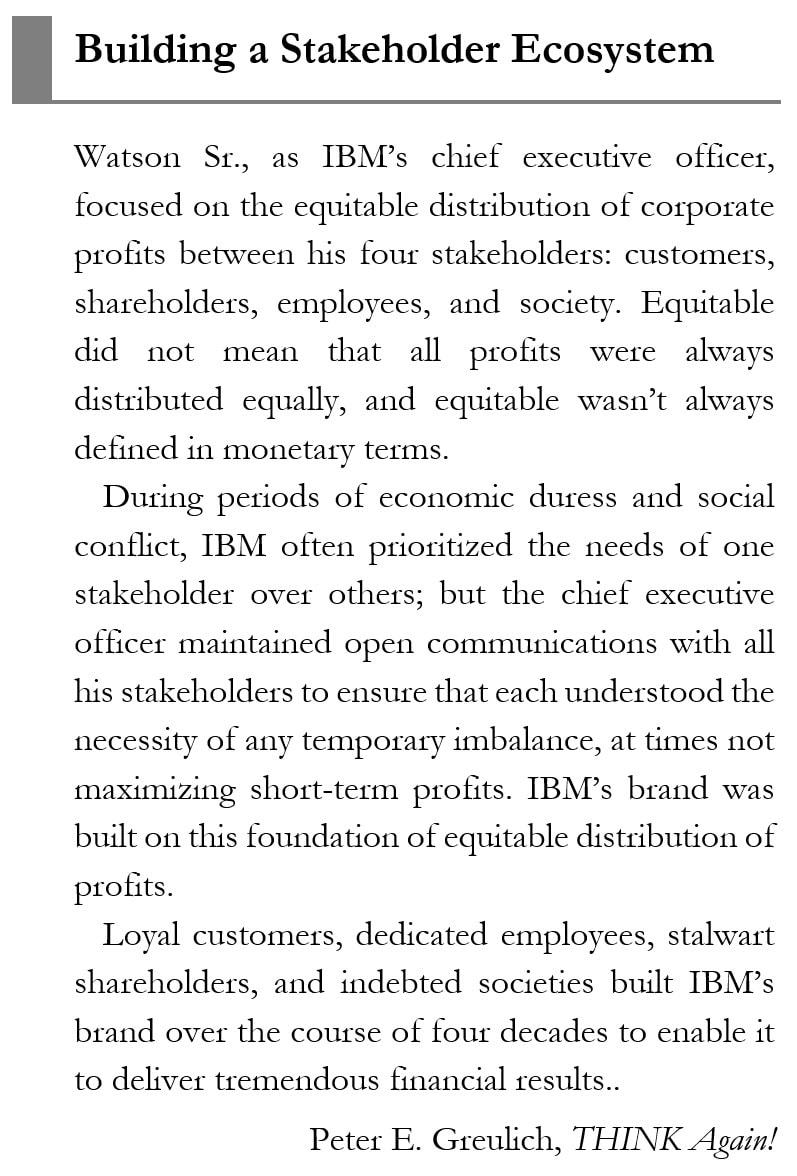

More practically, most of these industrialists viewed a capitalist as an individual whose money they put to work to provide a service to customers and jobs for others. Capitalists were the monetary engine of capitalism without which growth would have been more difficult and in many cases impossible. These industrialists understood the necessity of capitalists in their economic system and understood that one of their chief executive roles was to provide an adequate return on capital’s investment—adequate enough to keep them invested while being held at arm’s length. [see sidebar] |

George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak Company

kept his shareholders at arms length |

The returns of capitalists were considered in making decisions but when there was a strong chief executive in place, capitalists were rarely able to influence long-term, strategic business decisions. Harvey S. Firestone did not look kindly on chief executives who acted like capitalists.

"The moment that officers or directors of a company begin to speculate in its stock, the ruin of the company is not far away, for it is impossible to serve both the company and the stock market."

Harvey S. Firestone, Men and Rubber: The Story of Business

|

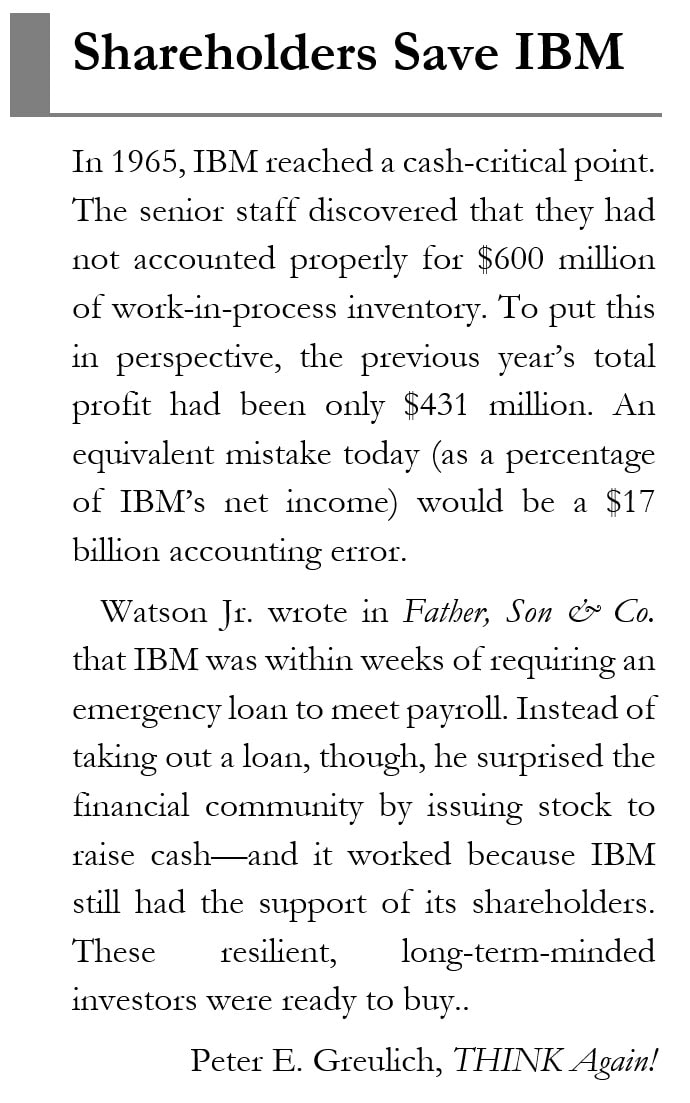

These industrialists balanced the needs of the business with their obligations to all their stakeholders, one of which was their shareholders. Watson Jr. wrote in his “Management Principles” (an extension to The Basic Beliefs) that the company had an obligation to provide an attractive return on invested capital. Attractive is the most subjective of adjectives – especially when it concerns money – and it requires a courageous and communicative CEO to set proper shareholder expectations around such a word.

Generally, it appears that most industrialists defined “attractive” as enough of a return to ensure that the existing shareholders retained their current investments and were ready to provide additional investments as needed. Tom Watson Sr. and his son found this balance successfully at IBM [see sidebar]. In 1922, even Henry Ford understood the necessity of cooperation between the stakeholders in a corporation. In his normal blunt manner, he put it this way: "No man is independent as long as he has to depend on another man to help him. It is a reciprocal relation—the boss is the partner of his worker, and the worker is partner of his boss. And such being the case, it is useless for one group or the other to assume that it is the one indispensable unit. Both are indispensable. The one can become unduly assertive only at the expense of the other—and eventually at its own expense as well. |

"It is utterly foolish for capital [capitalists] or for labor [employees] to think of themselves as groups. They are partners. When they pull and haul against each other—they simply injure the organization in which they are partners and from which both draw support. …

"There are short-sighted men who cannot see that business is bigger than any one man’s interests. Business is a process of give and take, live and let live. It is cooperation among many forces and interests. Whenever you find a man who believes that business is a river whose beneficial flow ought to stop as soon as it reaches him you find a man who thinks he can keep business alive by stopping its circulation.

"He would produce wealth by stopping the production of wealth."

"There are short-sighted men who cannot see that business is bigger than any one man’s interests. Business is a process of give and take, live and let live. It is cooperation among many forces and interests. Whenever you find a man who believes that business is a river whose beneficial flow ought to stop as soon as it reaches him you find a man who thinks he can keep business alive by stopping its circulation.

"He would produce wealth by stopping the production of wealth."

Here a Capitalist, there a Capitalist, everywhere a Capitalist - Capitalist

“Business exists to provide a service to MAN — service to consumer man, to worker man, to investor man, and to the community of man.”

THINK Magazine , July1956 [See Footnote]

Today, more so than any time in the history of capitalism, we embody in ourselves every aspect of these four stakeholders: consumers, employees, shareholders and society. With the advent of mutual funds, IRAs, 401(k)s in the private sector, and 403(b)s in the public sector, excess capital is being put to work to grow businesses through these instruments. The main difference is that these individuals are “closet capitalists.”

So, the definition of the 20th Century capitalists should be modified to reflect the new state of affairs: A capitalist is a person who has money invested in business enterprises—which may be an extensive amount of capital or minimal amounts accumulated into extensive amounts through mutual funds and retirement accounts such as a IRAs, 401(k)s or 403(b)s. Because of this shift in ownership, it is critical that there is a sustainable shareholder ecosystem which is balanced in its distribution of profits. More so today than ever before in the history of capitalism, it is deleterious to short shrift one stakeholder at the expense of another, such as labor for the perceived benefit of capital. In fact, it may be impossible!

So, the definition of the 20th Century capitalists should be modified to reflect the new state of affairs: A capitalist is a person who has money invested in business enterprises—which may be an extensive amount of capital or minimal amounts accumulated into extensive amounts through mutual funds and retirement accounts such as a IRAs, 401(k)s or 403(b)s. Because of this shift in ownership, it is critical that there is a sustainable shareholder ecosystem which is balanced in its distribution of profits. More so today than ever before in the history of capitalism, it is deleterious to short shrift one stakeholder at the expense of another, such as labor for the perceived benefit of capital. In fact, it may be impossible!

|

This is from the book, THINK Again! IBM CAN Maximize Shareholder Value.

"With the arrival of the twenty-first century, human nature still hasn’t changed, but stakeholders are, once again, more alike than they are distinct categories of men with might, money, or muscle. They have, in fact, returned to being one and the same. "Every individual, as they go through daily life, swaps out the mantles of different stakeholder personas. They are a consumer dropping off their children at a local day care; they are a worker assembling a new marketing campaign; they are an investor checking on their 401(k) retirement savings; and they are a member of a society that expects traffic signals — built by corporations and properly positioned by government entities — to keep them and their children safe on the communal roads home after work. "All individuals are consumers, workers, and investors; and all corporations are vested in the success or failure of their societies. "To say otherwise is ludicrous." |

Select image to read the Introduction to THINK Again!

|

If employees feel insecure in their jobs they will opt out of risky investments in stocks, and businesses will feel the effect of falling stock prices as workers withdraw their money (or quit investing) in such accounts.

Capitalism requires a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem.

Capitalism requires a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem.

Capitalism’s Foundation is a Strong Stakeholder Ecosystem

There is a natural tension between the four stakeholders in a corporation. It takes a strong chief executive officer to take the profits of a corporation and equitably distribute those gains between his or her stakeholders in such a manner as to strengthen these relationships and not weaken them. This is what great chief executive officers of the 20th Century did. They understood that their first job was to make their business profitable, but that their job also required a strong sense of fairness supported by even stronger communication skills to openly discuss the needs of each stakeholder. Their intent was to build a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem which would—in turn—protect the profitability of their corporations.

|

This can be seen in the 19th Century America. William Cooper Procter, who established one of the country’s first employee, profit sharing programs at Procter and Gamble in 1887 used balanced, rational words as he spoke to his employees about the needs of another corporate stakeholder: customers.

"The first job we have is to turn out quality merchandise that consumers will buy and keep on buying. If we produce it efficiently and economically, we will earn a profit, in which you will share. But profits can’t be distributed unless they are earned. And if the company is to take care of its equipment, expand normally, and remain in a sound financial position, part of the earnings must be plowed back into the business. That will safeguard your future, as well as the company’s." “Cooper” was all about business first, but IBM’s 21st Century chief executive officers, instead of plowing profits back into their business, have plowed $200 billion into paper—its stock. In so doing, they have fractured the stakeholder foundation of one of the strongest corporations in the United States of America. Their actions have set a standard despised by Henry Ford and most every industrialist who built this country. Their actions have forced a belief that capitalism stands for “every man for himself” in which every stakeholder pulls and hauls against the other.

This is greed's distortion of an honorable economic system. |

P&G was an early implementer of profit sharing, pensions, sick, death and disability benefits, and guaranteed employment.

|

It is an economic sickness.

The Author’s Perspective

As written above, Henry Ford understood the necessity of a sustainable stakeholder ecosystem. At Ford Motor Company, he maximized shareholder value, maximized customer value, maximized employee value and supported the economic and political societies they shared. As an example, his shareholders were rewarded beyond their wildest dreams: an investment of $10,000 in 1903 had, in thirteen years, delivered $6.6 million in dividends and was worth $35 million. This is a compounded annual rate of return of – wait for it – 89.8%.

|

Henry Ford wanted to reduce dividends to expand the River Rouge plant

|

Unfortunately, when Ford wanted to invest in one of the most massive industrial projects in the history of the United States, his shareholders weren’t satisfied with their booty. His shareholders sued him and sought to place his corporation in receivership to ensure their dividends would continue unabated.

This is an extreme of shareholder maximization which is better called shareholder‑first and ‑foremost. In Ford’s opinion this was not the way to maximize shareholder value and his shareholders were threatening the core value proposition of his business—providing a new, higher-quality, lower-priced product to his customers. |

This story is one of the most dramatic examples of shareholder-first and -foremost in the history of capitalism. In a very public manner, industrialist and capitalist (the shareholders) went to war. After the shareholders won a major battle in court, Henry won the war by staging an executive coup through the press. He took back control of his company [read the whole story here].

In this case, the chief executive stood tall for his company and his customers. This is not the case with many chief executives today. In this new century, instead of investing in a monumental project equivalent to building a River Rouge plant or shipping an industry-changing product like the System/360, the first three chief executives of IBM have invested in their own stock to construct a $200 billion paper pyramid. If a recession similar to the one a hundred years ago occurs—the Recession of 1920-21, it will burn this pyramid to the ground. Our economy and our country need stronger and more balanced chief executive officers.

What are the qualities a director should look for in a chief executive officer?

A corporation needs a business leader whose management style drives corporate-wide, interlocking, enlightened self-interests; a business leader who invests properly to ensure cooperation within a corporation; a business leader who produces wealth by increasing the production of wealth; a business leader who provides attractive returns to acquire and retain new capital but who also keeps these investors at arm’s length; and finally, a business leader who ensures a business flows corporate profits equitably between all its stakeholders with the communication skills to bind stakeholders together—so they do not pull and haul against each other.

As long as a corporation's board of directors finds and hires these qualities, the following words of Thomas J. Watson Sr. spoken at the Boston Jubilee on May 18, 1950 will continue to ring true:

In this case, the chief executive stood tall for his company and his customers. This is not the case with many chief executives today. In this new century, instead of investing in a monumental project equivalent to building a River Rouge plant or shipping an industry-changing product like the System/360, the first three chief executives of IBM have invested in their own stock to construct a $200 billion paper pyramid. If a recession similar to the one a hundred years ago occurs—the Recession of 1920-21, it will burn this pyramid to the ground. Our economy and our country need stronger and more balanced chief executive officers.

What are the qualities a director should look for in a chief executive officer?

A corporation needs a business leader whose management style drives corporate-wide, interlocking, enlightened self-interests; a business leader who invests properly to ensure cooperation within a corporation; a business leader who produces wealth by increasing the production of wealth; a business leader who provides attractive returns to acquire and retain new capital but who also keeps these investors at arm’s length; and finally, a business leader who ensures a business flows corporate profits equitably between all its stakeholders with the communication skills to bind stakeholders together—so they do not pull and haul against each other.

As long as a corporation's board of directors finds and hires these qualities, the following words of Thomas J. Watson Sr. spoken at the Boston Jubilee on May 18, 1950 will continue to ring true:

As I look into the future I see better things out there than I've ever seen before. We've built a capitalist system that nothing can ever shatter.

Thomas J. Watson Sr., May 18, 1950, The Salt Lake City Deseret News

We need men and women who build businesses to last:

Industrialist-minded chief executive officers.

Industrialist-minded chief executive officers.

Footnote: "A World Citizen Cited by Many Governments,” THINK Magazine, (IBM, New York, July 1956), p. 29.