If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

IBM's $35 Billion Acquisition Gamble: Red Hat

|

|

Date Published: July 28, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

Numbers that are in the billions and trillions seem all too unreal to the human mind. So, let’s add some business perspective to IBM’s $35.1 billion acquisition by breaking it down into digestible numbers and historical risks.

Some Business Thoughts on IBM's Red Hat Acquisition

- This Acquisition's Greatest Risk

- This Acquisition is about Wall Street-First

- Executive Experience with High-Visibility Acquisitions

- Red Hat and the Rise of Not-So-Good Goodwill

- The Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

This Acquisition’s Biggest Business Risk Is IBM’s Greatest Weakness

The following statements from Red Hat’s pre-acquisition 2018 Annual Report expose this acquisition’s human-risk factors:

It is understandable why IBM’s Human Relations organization no longer publishes its employee satisfaction numbers. Instead, it publishes what it does for its employees, not if what it is doing is actually effective. This is the equivalent of appraising an employee on hard work rather than effectiveness: kudos, but it misses the point.

Despite the nice picture that IBM’s Chief Human Resource Officer paints of her tenure for Forbes, the corporation’s human relation practices have been a two-decade-long drag on sales and profit productivity and – as a result – earnings per share.

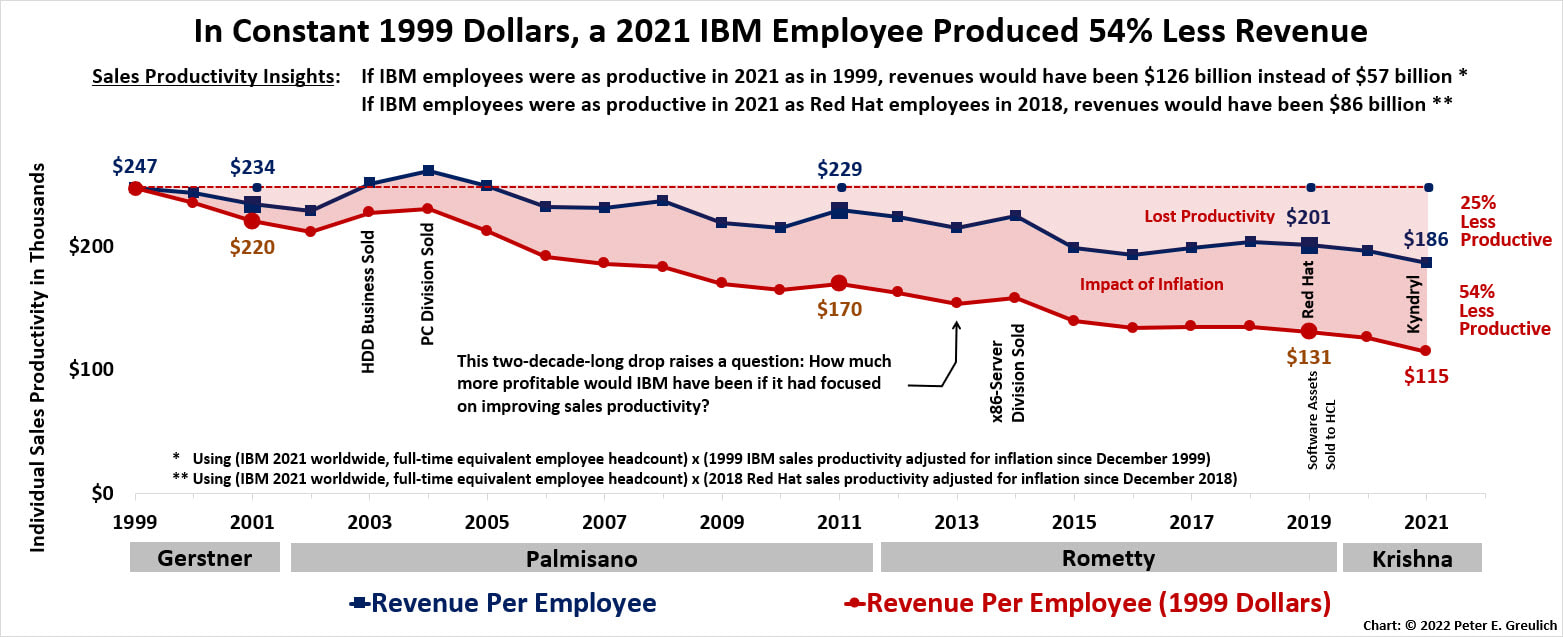

Here is IBM's twenty-first-century sales productivity as an example:

- Our corporate culture has contributed to our success, and if we cannot maintain this culture as we grow, we could lose the innovation, creativity and collaboration fostered by our culture, and our business may be adversely affected.

- We depend on our key employees, and our inability to attract and retain such employees could adversely affect our business or diminish our brands.

- We may not be able to continue to attract and retain capable management.

It is understandable why IBM’s Human Relations organization no longer publishes its employee satisfaction numbers. Instead, it publishes what it does for its employees, not if what it is doing is actually effective. This is the equivalent of appraising an employee on hard work rather than effectiveness: kudos, but it misses the point.

Despite the nice picture that IBM’s Chief Human Resource Officer paints of her tenure for Forbes, the corporation’s human relation practices have been a two-decade-long drag on sales and profit productivity and – as a result – earnings per share.

Here is IBM's twenty-first-century sales productivity as an example:

IBM’s Achilles’ heel is its human relations. If Gallup did an in-depth study of the corporation, it would find that its employees are not engaged; Deloitte would quickly discover that they aren’t passionate; and Tom Watson Sr., if he were alive today, would make it a priority—as he did in 1914—to improve employee enthusiasm. Why is this important?

Red Hat’s employee sales productivity at the end of 2017 was 20% higher than IBM’s, and its profit productivity was 34% higher (IBM’s profit productivity has been dropping significantly since 2013 and hit 21st Century lows in both 2017 and 2020). Red Hat’s employees, it would appear, were engaged, passionate and enthusiastic before the acquisition. Are they still?

The answer is noted in the chart above:

It seems that Big Blue is already impacting Big Red's productivity numbers. This should be an embarrassment since IBM paid approximately $3,000,000 per person ($35.1 billion for 11,870 employees as of February 28, 2018). This is an important number to remember as each Red Hat employee leaves, is resourced, or is picked off by the competition because Red Hat’s value to IBM is its people and their "innovation, creativity and collaboration."

The value of this acquisition deteriorates with each employee lost, not to mention the merger's loss of Red Hat's dynamic Chief Executive Officer: James Whitehurst.

Red Hat’s employee sales productivity at the end of 2017 was 20% higher than IBM’s, and its profit productivity was 34% higher (IBM’s profit productivity has been dropping significantly since 2013 and hit 21st Century lows in both 2017 and 2020). Red Hat’s employees, it would appear, were engaged, passionate and enthusiastic before the acquisition. Are they still?

The answer is noted in the chart above:

- If IBM employees were as productive in 2021 as Red Hat employees were in 2018, revenues would have been $86 billion, not $57 billion.

- If IBM employees were as productive in 2021 as Red Hat employees in 2018, profits would have been $11.3 billion, not $5.7 billion.

It seems that Big Blue is already impacting Big Red's productivity numbers. This should be an embarrassment since IBM paid approximately $3,000,000 per person ($35.1 billion for 11,870 employees as of February 28, 2018). This is an important number to remember as each Red Hat employee leaves, is resourced, or is picked off by the competition because Red Hat’s value to IBM is its people and their "innovation, creativity and collaboration."

The value of this acquisition deteriorates with each employee lost, not to mention the merger's loss of Red Hat's dynamic Chief Executive Officer: James Whitehurst.

IBM’s Acquisition and Divestiture Strategy Is about Wall Street-First

|

Is it time to sell?

|

Most analysts have been focusing on IBM’s $190 per share purchase price or the market’s reaction to the announcement, but only Wall Street speculators and side-show commentators care about the short-term price of paper and speculative news or rumors.

The real question is how long will it take to pay off this acquisition? Is it a rational expenditure of greenbacks? Would the company be better served spending the money elsewhere? Should it have paid less? After spending $201 billion on share buybacks since 1995, why didn't the executive team ask for some of that money back with a stock offering to fund the acquisition, similar to what Thomas J. Watson Jr. did in 1965? |

Were they afraid no one would buy into the offering? [See Footnote]

Red Hat’s average net income over its last ten years had been $164 million and its latest net income was $258 million (Red Hat’s 2018-19 Annual Report). The purchase price was one hundred thirty-five times Red Hat’s highest yearly net income and more than two hundred times its ten-year average. Wouldn’t it be hard for a small business man or woman to justify a $500,000 business loan to purchase a competitor that had a yearly net income of less than $5,000 and a ten-year, average net income of half that number?

Even decisions that are measured in billions should be subject to an economic justification. If this acquisition doesn’t meet expectations, it is reasonable to expect IBM’s Chief Executive Officer to spin off the company, its products, and its customers like the company has other acquisitions and whole divisions whose products were of strategic value to the corporation's customers but not necessarily to IBM's corner office.

IBM’s decades of acquisitions and divestitures demonstrate that the chief executives have prioritized their earnings-per-share strategy over their own customers’ strategic investments in the company’s products. It has never been a good, long-term business strategy to alienate customers.

These are bad, short-term, stock-price manipulations that have been going on for too long.

One does get the feeling that this acquisition was a Hail Mary acquisition.

Red Hat’s average net income over its last ten years had been $164 million and its latest net income was $258 million (Red Hat’s 2018-19 Annual Report). The purchase price was one hundred thirty-five times Red Hat’s highest yearly net income and more than two hundred times its ten-year average. Wouldn’t it be hard for a small business man or woman to justify a $500,000 business loan to purchase a competitor that had a yearly net income of less than $5,000 and a ten-year, average net income of half that number?

Even decisions that are measured in billions should be subject to an economic justification. If this acquisition doesn’t meet expectations, it is reasonable to expect IBM’s Chief Executive Officer to spin off the company, its products, and its customers like the company has other acquisitions and whole divisions whose products were of strategic value to the corporation's customers but not necessarily to IBM's corner office.

IBM’s decades of acquisitions and divestitures demonstrate that the chief executives have prioritized their earnings-per-share strategy over their own customers’ strategic investments in the company’s products. It has never been a good, long-term business strategy to alienate customers.

These are bad, short-term, stock-price manipulations that have been going on for too long.

One does get the feeling that this acquisition was a Hail Mary acquisition.

IBM Has Little Proven Expertise with Acquisitions of this Visibility

|

From 2001 through 2018, IBM had acquired 184 companies—an average of ten per year or almost one a month—at a total purchase price of $52 billion. Its largest acquisition was Cognos at $5 billion and the average acquisition size was $283 million. IBM’s 184 acquisitions were so numerous, came so fast, and were monetarily, so individually insignificant that few received any attention beyond the initial acquisition’s press release.

This purchase dwarfed the corporation’s largest twenty-first-century acquisition by seven times and was an astronomical one hundred and twenty times larger than its average acquisition. This acquisition is being watched. There will be press’ and analysts’ bullseyes focused on how well IBM wears its Red Hat. |

This begs the question as to who at IBM has the experience to successfully integrate the talents of such a visible acquisition. James Whitehurst would have been a logical choice, but he is out of the picture. IBM, as a corporation of 400,000 (reduced to 300,000 in 2021) with all its arcane polices and human resource problems, can easily overwhelm a corporation of 12,000 causing drops in sales and profit productivity. If growth numbers disappoint, or if the company attempts to obfuscate these numbers (as it has its strategic imperative numbers), we should hope that the "free" press and "competent" analysts will call its bluff on an acquisition of this size. This could force a goodwill impairment of significant magnitude.

With the wrong executive leadership, this acquisition could easily become IBM’s equivalent of HP’s Autonomy or Microsoft’s Nokia, as IBM's financial organization doesn't understand the difference between talking about a vision and providing the necessary funds to train people and improve processes to deliver profitable, competitive products to market.

This twenty-first-century corporation is led by jettison-now management, not managed by turn-around leadership. It will be interesting to see if Arvind Krishna—without James Whitehurst—can or has the will to rein in the financial organization.

With the wrong executive leadership, this acquisition could easily become IBM’s equivalent of HP’s Autonomy or Microsoft’s Nokia, as IBM's financial organization doesn't understand the difference between talking about a vision and providing the necessary funds to train people and improve processes to deliver profitable, competitive products to market.

This twenty-first-century corporation is led by jettison-now management, not managed by turn-around leadership. It will be interesting to see if Arvind Krishna—without James Whitehurst—can or has the will to rein in the financial organization.

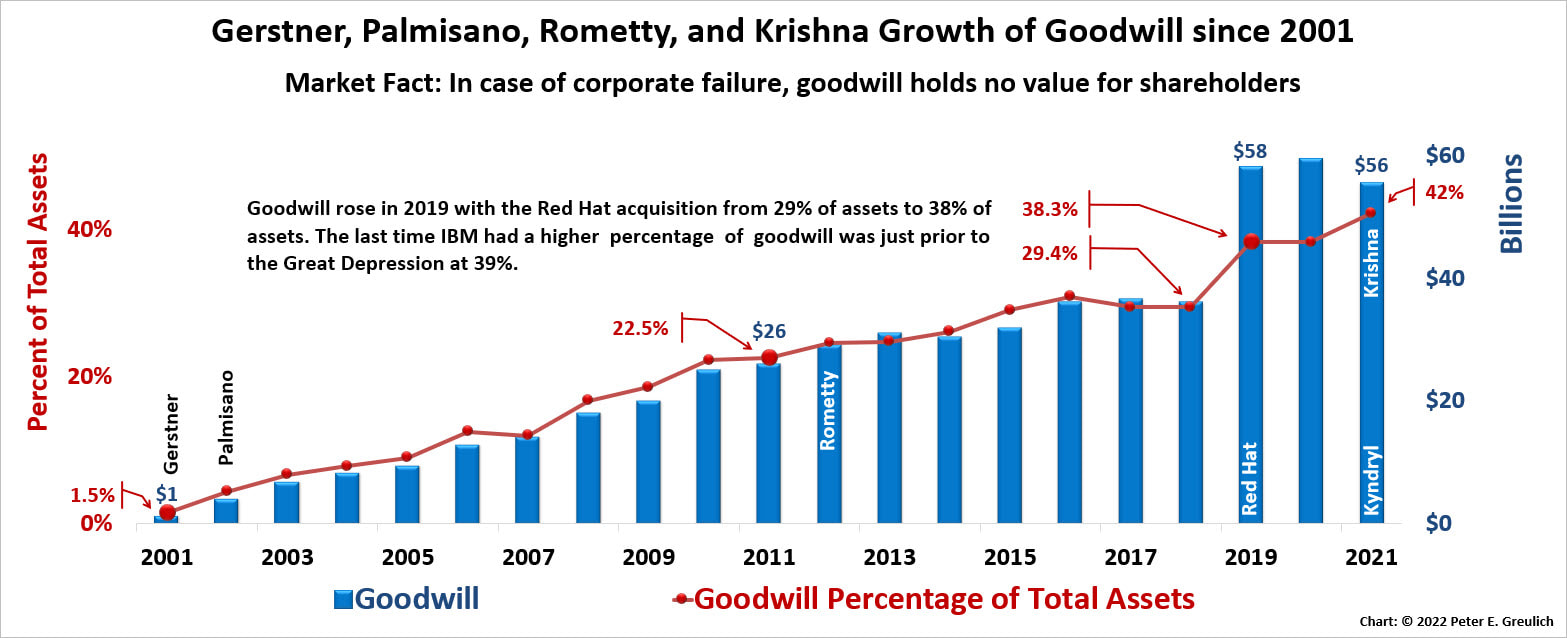

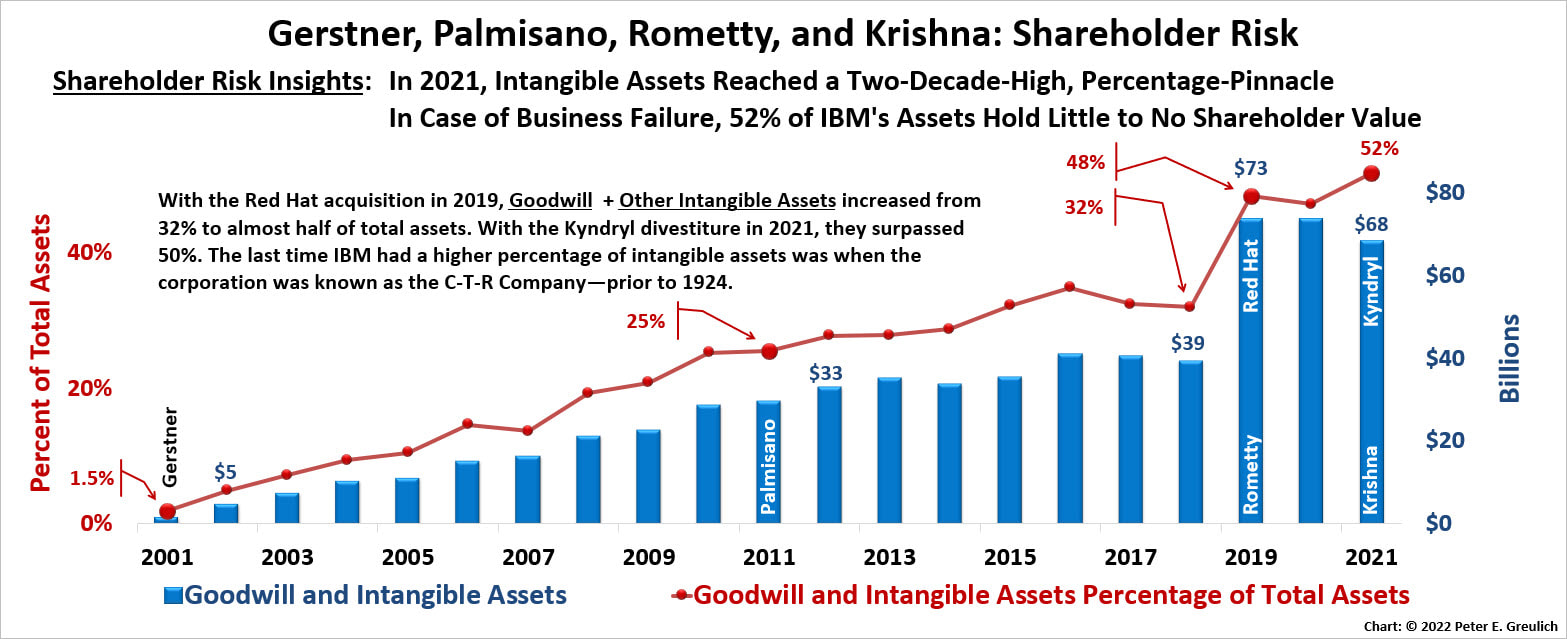

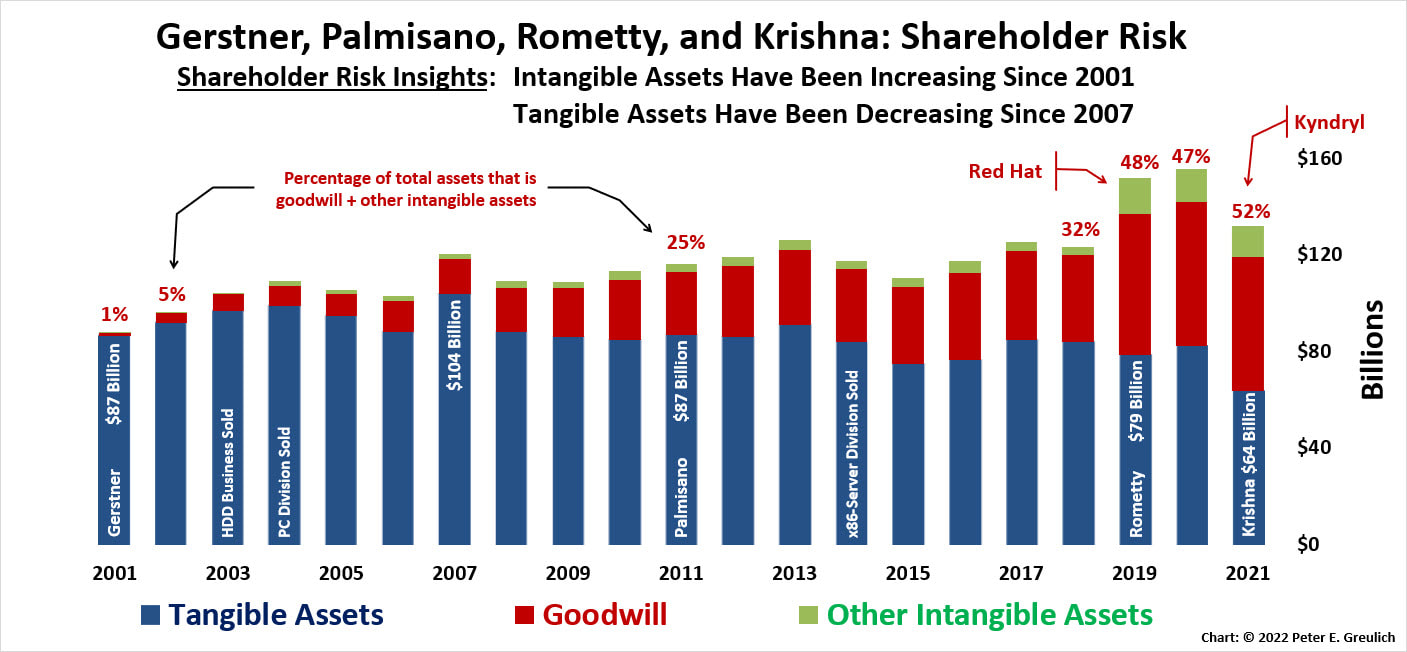

Red Hat and the Continuing Rise of Not-So-Good Goodwill at IBM

IBM is carrying on its books 71% of all its acquisition dollars since 2001 as an intangible asset called goodwill. Its acquisitions have not been in tangible assets such as manufacturing facilities or office buildings but in that “intangible” gray matter located between its acquired assets’ two ears. This human asset can lose his or her value slowly as productivity melts away in disillusionment, or it can be lost quickly to a competitor if the new work environment proves too toxic to bear. With bad management, investors should remember that human – intangible – assets are subject to the saying, "Here today, gone tomorrow"—physically, mentally or emotionally.

The IBM 2019 Annual Report reflected the one-year's growth in goodwill and all intangible assets with the acquisition of Red Hat: (1) goodwill of $23.125 billion, (2) client relationships valued at $7.215 billion, (3) technology of $4.571 billion, and (4) trademarks of $1.686 billion. Out of all the "assets" acquired, only $4.125 billion (10% of all assets) were in cash, cash equivalents, property, plant, and equipment.

The charts below have been updated with information from IBM's 2020 and 2021 Annual Reports:

The IBM 2019 Annual Report reflected the one-year's growth in goodwill and all intangible assets with the acquisition of Red Hat: (1) goodwill of $23.125 billion, (2) client relationships valued at $7.215 billion, (3) technology of $4.571 billion, and (4) trademarks of $1.686 billion. Out of all the "assets" acquired, only $4.125 billion (10% of all assets) were in cash, cash equivalents, property, plant, and equipment.

The charts below have been updated with information from IBM's 2020 and 2021 Annual Reports:

- The Growth of Goodwill since 2001

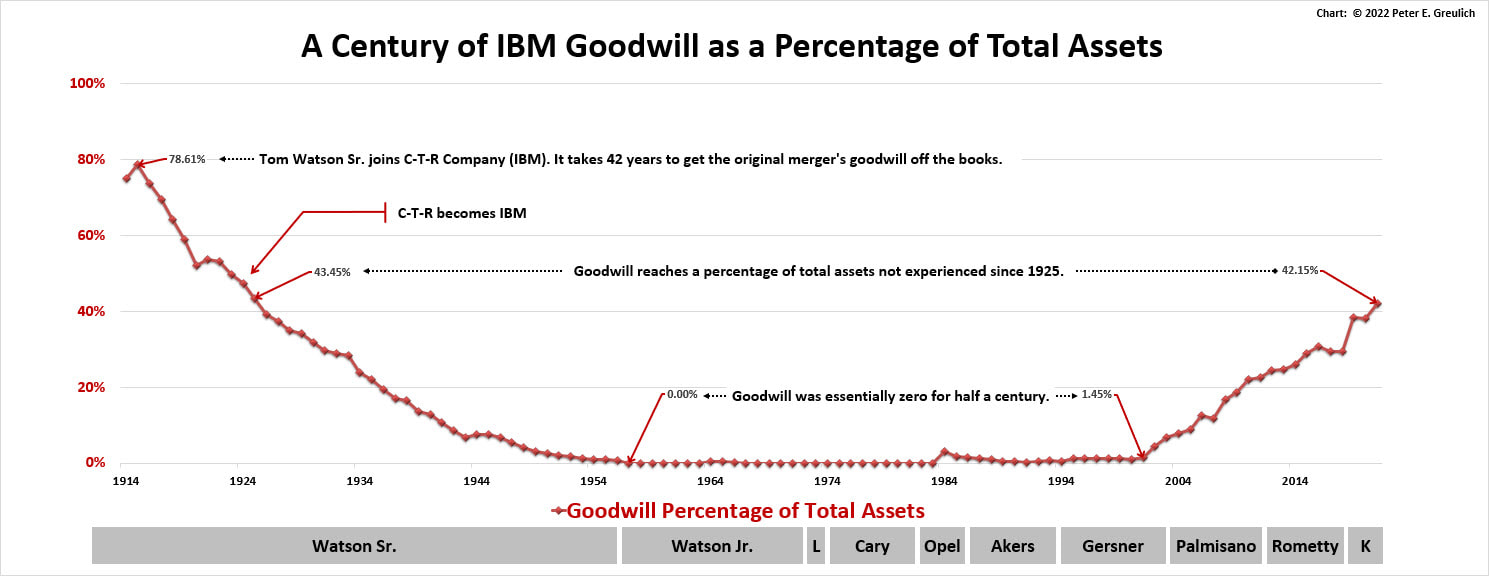

- IBM's 2021 Percentage of Goodwill Hasn't Been this High since the Corporation Was Known as the C-T-R Company

- The Growth of Goodwill + Intangible Assets since 2001

- A Total Assets Mirage: Tangible Assets Are Declining while Goodwill and Intangible Assets Are Growing

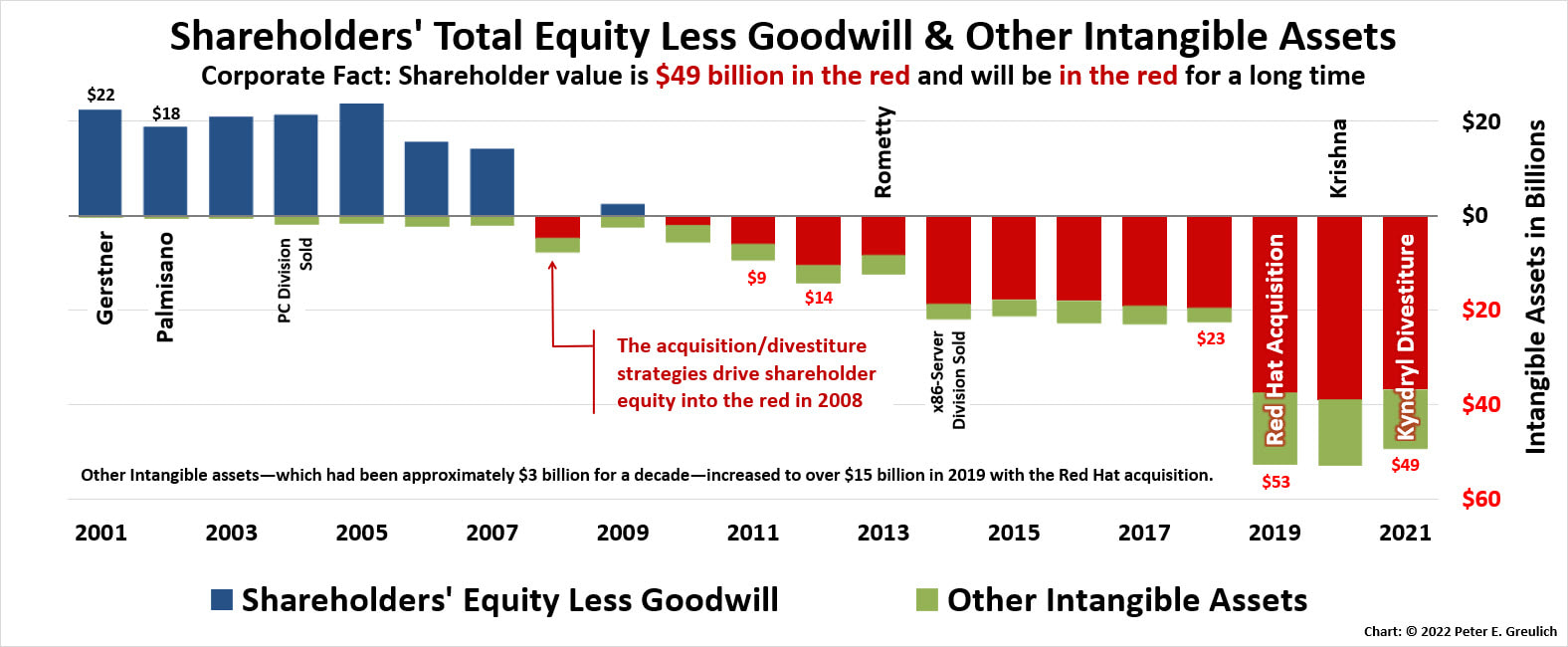

IBM justifies this goodwill every year – as it has since 2006 – with its normal cut-and-paste into its annual report: “The primary drivers that generate goodwill are the value of synergies between … the company and the acquired assembled workforce.” Unfortunately, the synergies of its previous 184 workforce acquisitions (207 acquisitions as of the end of 2021) have failed to materialize, as IBM’s sales and profit productivity continues to fall. Total shareholder equity less goodwill reflects the overriding importance of these acquired human assets—the human synergies upon which this goodwill is based.

This Red Hat acquisition might finally cause a few of the larger, more powerful shareholders to start asking questions as shareholder equity less goodwill has fallen significantly further into the red, and shareholder equity less all intangibles reached scary amounts and a significant percentage of total assets.

This Red Hat acquisition might finally cause a few of the larger, more powerful shareholders to start asking questions as shareholder equity less goodwill has fallen significantly further into the red, and shareholder equity less all intangibles reached scary amounts and a significant percentage of total assets.

- Shareholders' Equity Less Goodwill and Intangible Assets

Shareholders may soon awaken to the realization that the only way to maximize shareholder value is to maximize stakeholder value through an equitable distribution of profits between shareholders, customers, employees and society—the corporation's four investors. As the three charts above show, IBM's human assets - synergies of acquired workforces - have reached half of total assets.

Just as a piece of machinery needs maintenance or it breaks down, the human being needs investments to maximize its efficiency in the workplace.

Just as a piece of machinery needs maintenance or it breaks down, the human being needs investments to maximize its efficiency in the workplace.

This Author's Thoughts and Perceptions

After some study, it is apparent why Red Hat’s shareholders approved this acquisition. They cashed out. It is hard, though, to see how this acquisition is proving to be of any benefit to IBM’s long-term shareholders other than in short-term marketing hype. It is not the type of acquisition that will shake the corporation out of its two-decade-long, shareholder-return slump. This is more of the same: a two-decade-long, wrong-headed, dual strategy of investing in paper and acquisitions instead of making the corporation's people more productive, its processes more effective, and producing products of higher value through long-term, customer-focused, internal research investments.

IBM needs to invest in game-changing, bet-the-business initiatives within its industry or march in place, marshal its resources and put its top distinguished engineers to work calculating where to make profitable micro-investments until the next market shift happens – and then lead. Historically, IBM has used such strategies to take market share from its competitors during down economies. (see IBM’s Crises, Recoveries and Lessons Learned)

With this acquisition, IBM is following the herd into a territory in which it has little expertise: low-priced, highly-commoditized, and extremely competitive markets. It has rarely been successful in being the short-term, low-price, producer of anything. Its success has always been in selling the highest-priced but long-term, lowest-cost, solution that sticks—such as the System/360 (mainframe) or AS/400. This acquisition doesn’t fit the later model and any transformation that takes IBM in the direction of the former, is a mistake of the greatest magnitude.

As always, a humble opinion – derived from on-going research – that is expressed with great passion and concern for the corporation, its people and my friends who depend on the company for their pensions, dividends and paychecks.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

IBM needs to invest in game-changing, bet-the-business initiatives within its industry or march in place, marshal its resources and put its top distinguished engineers to work calculating where to make profitable micro-investments until the next market shift happens – and then lead. Historically, IBM has used such strategies to take market share from its competitors during down economies. (see IBM’s Crises, Recoveries and Lessons Learned)

With this acquisition, IBM is following the herd into a territory in which it has little expertise: low-priced, highly-commoditized, and extremely competitive markets. It has rarely been successful in being the short-term, low-price, producer of anything. Its success has always been in selling the highest-priced but long-term, lowest-cost, solution that sticks—such as the System/360 (mainframe) or AS/400. This acquisition doesn’t fit the later model and any transformation that takes IBM in the direction of the former, is a mistake of the greatest magnitude.

As always, a humble opinion – derived from on-going research – that is expressed with great passion and concern for the corporation, its people and my friends who depend on the company for their pensions, dividends and paychecks.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

Footnote: Watson Jr. wrote in his book Father, Son and Company about the increased competition as he was making the shift from tabulating machines to computers in the early '60s. It appears the market saw this competition too. He would write in his book that in the autumn of 1965, after announcing the System/360 in April of 1964, everything looked "black, black, black" as the company clung to "its production schedule" but "morale was going down." The company came within weeks of needing to borrow money to meet its payroll obligations. He "surprised" the market with a new stock offering to cover the costs of building the new hardware platform. The shareholders kept their faith in his leadership and the company's ability to deliver. The new stock offering was fully subscribed.