How Much Is a Great CEO Worth?

- Politicians Try to Make Executive Pay Transparent but Fail

- Headlines Embarrass Two Great Chief Executives

- Stakeholders Define Executive Greatness

- So, How much Is a Great Chief Executive Worth?

Politicians Pass A Law to Make Executive Pay Transparent but Fail

|

An executive shakedown

|

The Revenue Act of 1934 required the United States Treasury to publish the names of corporate officials making more than $15,000 in salaries, commissions and bonuses. Published during the time of tabulating machines, the eleven-hundred-page report listed almost fifty thousand individuals from more than eight thousand corporations.

It was a chaotic scene when the report was initially released, as reporters fought to be the first in line for what was a guaranteed top story: revealing to the world that year’s highest paid individual, or industrialist, movie mogul, entertainer or woman. After seeing the commotion with the release of the report in January 1936, Chairman Doughton of the House Ways and Means Committee suspended access, commenting that the list might get “disarranged or possibly lost.” |

The highest paid individual could also be very fluid as the Treasury updated the report as corporations closed out their fiscal years. A business-section headline of the New York Post on May 6, 1936, read, “Watson’s Pay of $303,813 Tops ’35 List.” Less than thirty days later, a business-section headline of the same paper read, “Sloan Highest Paid Executive with $374,505.” By the end of the year, Watson Sr. ended up rather far down the list as the final winner was William Randolph Hearst at $500,000 and Mae West, “the throaty-voiced siren of the screen” running a close second at $450,833 topping such men of fame as Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers and Fred Astaire.

The report also had its flaws. Not included were incomes from dividends, proprietorships, partnerships, rents or royalties; neither did the act consolidate salaries received from multiple corporations. Many Hollywood stars formed corporations to produce their movies and then received their earnings as dividends. The report also did not measure wealth, as incomes from the capital investments of the nation’s richest families—the Du Ponts, Rockefellers, Fords or Morgans—escaped scrutiny.

The report also had its flaws. Not included were incomes from dividends, proprietorships, partnerships, rents or royalties; neither did the act consolidate salaries received from multiple corporations. Many Hollywood stars formed corporations to produce their movies and then received their earnings as dividends. The report also did not measure wealth, as incomes from the capital investments of the nation’s richest families—the Du Ponts, Rockefellers, Fords or Morgans—escaped scrutiny.

|

In 1940, Congress reduced the list of executives from the top-paid 50,000 to the top-paid 400 by sharpening the act’s focus on those earning $75,000 or more, but they failed to fix its other obvious shortcomings.

So, with the advent of World War II, an individual earning a $75,000+ salary but leading an industrial charge to produce vital war materials for democracy would constantly be in the public eye while another individual receiving $1,000,000 from investments but paying comparatively little in taxes to support the war effort did not even register as a blip on the modified act’s radar screen. |

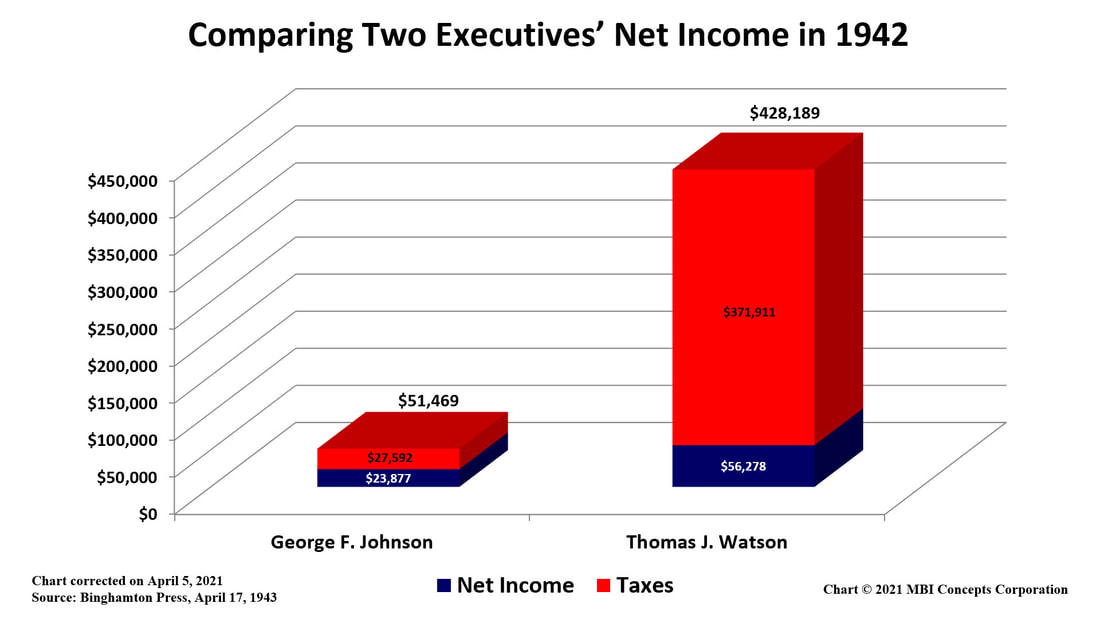

The effect of federal taxes on executive pay in 1942

|

Not fair? Surely, but factual. Only a few good newspapers, reporters and editorialists acknowledged these shortcomings or examined the minimal difference between corporate executives’ high salaries in after-tax dollars—tax payments ranged over seventy percent on these high earners.

For more than a decade, most papers just repeated the sensational headlines without context.

For more than a decade, most papers just repeated the sensational headlines without context.

Headlines Embarrass Two Great Chief Executives

In 1934, Thomas J. Watson Sr. earned $365,358 in salary, commissions and director’s fees. It was an unfortunate number because it was a natural headline maker. He became “The $1,000-A-Day Man.”

To wrap a modern context around what a worker might have felt when reading this headline, an early 1930’s information technology worker—a tabulating machine operator—earned from $1,000 to $1,500 a year. IBM’s Chief Executive matched their yearly earnings in a day. If Watson were alive today and earned in a day what an average IT operator earned last year, he would be making $85,000 a day or $31 million a year. It is understandable why this sound-bite made headlines: During the Great Depression it was newsworthy, and it sold papers.

Of the thousands of articles published, though, not a single article covered the history of Watson Sr.’s long-term compensation package. His overall earnings were significant, but his pay was directly linked to the corporation’s performance. In 1914, he started at a salary of $25,000 a year and, with profit sharing, averaged $80,000 a year through the end of the decade. After the corporation survived the Recession of 1920-21, his salary increased to $60,000 a year and his commissions were broadened in scope—presumably reaching the level of 5% on all corporate profits after paying $6.00 in annual dividends. As the Great Depression bottomed out in the years of 1933-34, his salary peaked at $100,000 per year, but because of IBM’s performance, commissions were the lion’s share of his total pay—in 1934, $264,432 of the $365,358. He was always, as Charles R. Flint put it when he hired him, getting a “part of the ice he cut.”

The hallmark characteristic of Tom Watson’s time as IBM’s chief executive was the equitable distribution of corporate profits between all his stakeholders; and his open communication of the value of these investments in employee benefits, shareholder dividends and customer products, that created a like-minded, sustainable stakeholder community. If anyone thinks that these stakeholders were overly concerned with Watson Sr.’s pay as their chief executive officer, their response to the federal act’s salary disclosures settles this question.

It was less than a year after the trough of the Great Depression, that the press started publishing the salaries of the chief executives in the United States. It was dark economic times for the country. The front-page headlines embarrassed many of the better executives. George F. Johnson, Chairman of the Board of the Endicott-Johnson Corporation, wrote in his factories’ hometown newspaper in Binghamton, New York:

"Some people would feel honored to see their names in a list of American citizens reported as having ‘a million dollars a year income.’ The effect of such a publication, to me, is disgusting. I am ashamed and mortified. … Any man who dies rich, dies disgraced especially in times like the present, when so many men, women and children are suffering for the common necessities of life."

He goes on to explain how he has been investing in the business during the depression and shared the profits from the corporation with his employees, shareholders and the local tri-cities community: “in the neighborhood of twenty-six to twenty-eight million dollars in cash and stock.”

To wrap a modern context around what a worker might have felt when reading this headline, an early 1930’s information technology worker—a tabulating machine operator—earned from $1,000 to $1,500 a year. IBM’s Chief Executive matched their yearly earnings in a day. If Watson were alive today and earned in a day what an average IT operator earned last year, he would be making $85,000 a day or $31 million a year. It is understandable why this sound-bite made headlines: During the Great Depression it was newsworthy, and it sold papers.

Of the thousands of articles published, though, not a single article covered the history of Watson Sr.’s long-term compensation package. His overall earnings were significant, but his pay was directly linked to the corporation’s performance. In 1914, he started at a salary of $25,000 a year and, with profit sharing, averaged $80,000 a year through the end of the decade. After the corporation survived the Recession of 1920-21, his salary increased to $60,000 a year and his commissions were broadened in scope—presumably reaching the level of 5% on all corporate profits after paying $6.00 in annual dividends. As the Great Depression bottomed out in the years of 1933-34, his salary peaked at $100,000 per year, but because of IBM’s performance, commissions were the lion’s share of his total pay—in 1934, $264,432 of the $365,358. He was always, as Charles R. Flint put it when he hired him, getting a “part of the ice he cut.”

The hallmark characteristic of Tom Watson’s time as IBM’s chief executive was the equitable distribution of corporate profits between all his stakeholders; and his open communication of the value of these investments in employee benefits, shareholder dividends and customer products, that created a like-minded, sustainable stakeholder community. If anyone thinks that these stakeholders were overly concerned with Watson Sr.’s pay as their chief executive officer, their response to the federal act’s salary disclosures settles this question.

It was less than a year after the trough of the Great Depression, that the press started publishing the salaries of the chief executives in the United States. It was dark economic times for the country. The front-page headlines embarrassed many of the better executives. George F. Johnson, Chairman of the Board of the Endicott-Johnson Corporation, wrote in his factories’ hometown newspaper in Binghamton, New York:

"Some people would feel honored to see their names in a list of American citizens reported as having ‘a million dollars a year income.’ The effect of such a publication, to me, is disgusting. I am ashamed and mortified. … Any man who dies rich, dies disgraced especially in times like the present, when so many men, women and children are suffering for the common necessities of life."

He goes on to explain how he has been investing in the business during the depression and shared the profits from the corporation with his employees, shareholders and the local tri-cities community: “in the neighborhood of twenty-six to twenty-eight million dollars in cash and stock.”

The Stakeholders Define Executive Greatness

Tom Watson explained his salary and commission structure while standing in front of his annual shareholder meetings. He also explained to shareholders the value of continuing to invest in the corporation’s human assets—its employees. Then he explained to employees why the shareholders—the owners of the corporation—were due a fair return on their investments. In essence, he was explaining how all of them were sharing equitably in the ice "they all cut."

In 1934, at his twentieth annual meeting with shareholders—with more than seventy-seven percent of the stock represented in the audience, and at that time, the second largest percentage of stock representation in the history of the company—the shareholders passed the following resolution:

"The stockholders here present at the annual meeting of the International Business Machines Corporation do hereby express their appreciation to Thomas J. Watson, their president, for his matchless achievements as their president during a long term of years, and for his honesty, integrity and worth as its executive officer. The manner in which he carried our corporation through the depression has been masterful. We express our supreme confidence in him."

In 1934, at his twentieth annual meeting with shareholders—with more than seventy-seven percent of the stock represented in the audience, and at that time, the second largest percentage of stock representation in the history of the company—the shareholders passed the following resolution:

"The stockholders here present at the annual meeting of the International Business Machines Corporation do hereby express their appreciation to Thomas J. Watson, their president, for his matchless achievements as their president during a long term of years, and for his honesty, integrity and worth as its executive officer. The manner in which he carried our corporation through the depression has been masterful. We express our supreme confidence in him."

|

The shareholders’ appreciation is probably best understood by evaluating the returns of the stockholders in IBM’s top competitor during this time: Remington Rand. The Rand Corporation had stopped dividend payments in 1931 and didn’t announce their resumption until April 1936.

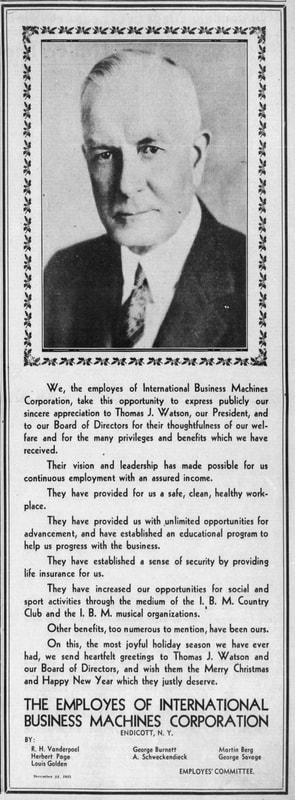

In 1935, the employees of IBM Endicott took out an advertisement in The Binghamton Press to express their support. In the newspaper insert, they clearly articulate their perception of the critical benefits accrued under his leadership:

IBM’s customers, employees and shareholders—just like IBM’s chief executive—believed in paying for performance. B. C. Forbes wrote about the on-going controversy over executive payments in his editorials. He highlighted several shareholder communities that had supported their chief executives as well as one Senator who, while attacking the executives, was avoiding paying his own share of federal taxes. Forbes ended the article with, “It would be a sad, tragic day for America were everybody to reach the conclusion all business men, all employers, all executives were conscienceless grasping crooks, intent only upon self-aggrandizement.” It would have been a sad day then – and it would be a tragic day now. |

Especially, when the country needs new turn-around corporate leadership not jettison-now management—just like during the Depression.

So, How Much Is a Great Chief Executive Worth?

"When one serves for the sake of service—for the satisfaction of doing that which one believes to be right—then money abundantly takes care of itself. Money comes naturally as the result of service."

Henry Ford, My Life and Work

A study of IBM’s history of successes and failures substantiates Henry Ford’s perspective that a chief executive’s overall performance is directly associated with their personal priorities: (1) if an executive’s primary motivation is a self-serving, short-term monetary gain, stakeholders should expect a lackluster, long-term performance—usually coming at the expense of one – or all – of the members within their community; (2) if an executive’s primary motivation is to grow long-term corporate wealth by building a sustainable, supportive stakeholder community, then strong, long-term, balanced returns can be anticipated.

|

In a word, the worth of the latter of these chief executive officers is priceless. Such chief executives know that corporate survival and long-term adaptability is about business-first: maintaining a long-term investment strategy to make people more productive, processes more effective, products more valuable, and then to clearly articulate this strategy to customers, employees, shareholders and their common societies to ensure a knowledgeable, unified and supportive stakeholder community.

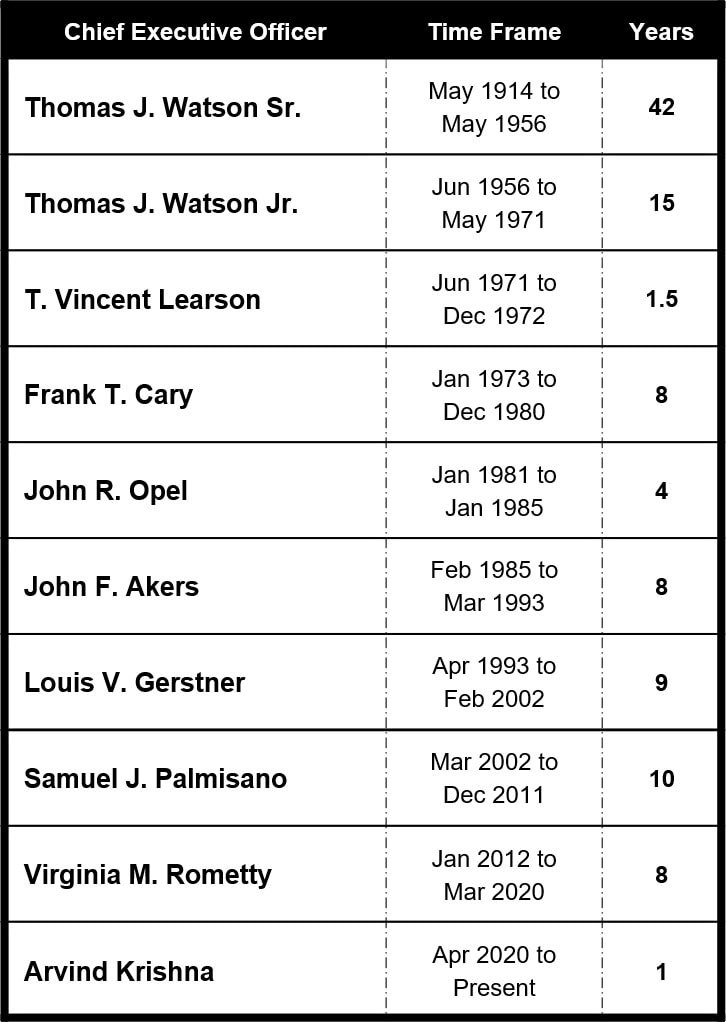

For almost seven decades, this was IBM’s corporate direction and a driving purpose of its first four chief executives: Watson Sr., Watson Jr., T. Vincent Learson, and Frank T. Cary. These chief executives invested in the business first and had the desire and ability to set realistic stakeholder expectations through constant open communications.

Again, how much is a great corporate executive worth? As with Watson Sr. in the 1930s, to the corporation’s customers, employees and shareholders—no matter what a great chief executive earns—it will seem superficial compared to the service they provide within their common societies. Such individuals are rewarded with both stakeholder loyalty and money. |

IBM’s Greatest Chief Executive Officers placed more value on loyalty, and the money came to them naturally as a result of their service.