If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

IBM First-Year (2019) Red Hat Revenue

|

|

Date Published: January 31, 2020

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

This chart is purposely scaled so that the reader may see the change in Red Hat's revenue over time and, specifically, 2018-2019—the first year of the acquisition. Without this scale the Red Hat revenue would be such a miniscule part of IBM's total revenue that it would not be visible.

An Evaluation of IBM's Red Hat Acquisition and its 2019 Financial Results

- The Wall Street Perspective in Print

- The Revenue Facts: Charting Virginia M. Rometty's Performance

- How Has IBM Historically Produced Stable, Growing Revenue?

- What Is the Revenue Big Picture?

- IBM Isn't Firing on all Cylinders

- Three Decades Ago, IBM Fell in a Hurry

- Author's Opinion: Falling Revenue is a Symptom of Bigger Issues

The Wall Street Perspective in Print

Depending on what publication you read, it have may sounded like IBM turned a corner in its January 21, 2020 earnings announcement:

For the most part, Wall Street analysts found excitement in IBM’s latest quarter: the company raised revenue in the fourth quarter of 2019 over 2018 by .078125%. Yes, the decimal point is in the right place: $21,777 billion in the fourth quarter of 2019 vs. $21,760 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018. (To remove the vagueness of billions, this is the equivalent of a thousand-dollar-a-quarter company doing an additional .78 cents, or a million-dollar-a-quarter company doing an additional $780.)

It would take more than this to excite a true business analyst, eh?

- Seeking Alpha wrote:

- Business Insider wrote:

- Motley Fool wrote:

- WRAL TechWire went all out:

- The Wall Street Journal joined the parade … cautiously:

- Forbes added a literal “but” to its title, while the Financial Times suggested one:

For the most part, Wall Street analysts found excitement in IBM’s latest quarter: the company raised revenue in the fourth quarter of 2019 over 2018 by .078125%. Yes, the decimal point is in the right place: $21,777 billion in the fourth quarter of 2019 vs. $21,760 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018. (To remove the vagueness of billions, this is the equivalent of a thousand-dollar-a-quarter company doing an additional .78 cents, or a million-dollar-a-quarter company doing an additional $780.)

It would take more than this to excite a true business analyst, eh?

The Revenue Facts: Charting Virginia M. Rometty’s Performance

IBM’s problems started in 1995, and they have been on-going for more than two decades. Its sales and profit productivity flattened in 1995 and started their decline in 1999. This is a first in IBM’s 100+ year history and a sign of the cultural mess the company has become.

Virginia M. Rometty inherited this fiasco from Gerstner and Palmisano, but her actions, similar to theirs, exacerbated the problem. It will take more than a .078125% improvement in quarterly revenue—especially after paying $34 billion for Red Hat—to claim the problems are fixed.

Virginia M. Rometty inherited this fiasco from Gerstner and Palmisano, but her actions, similar to theirs, exacerbated the problem. It will take more than a .078125% improvement in quarterly revenue—especially after paying $34 billion for Red Hat—to claim the problems are fixed.

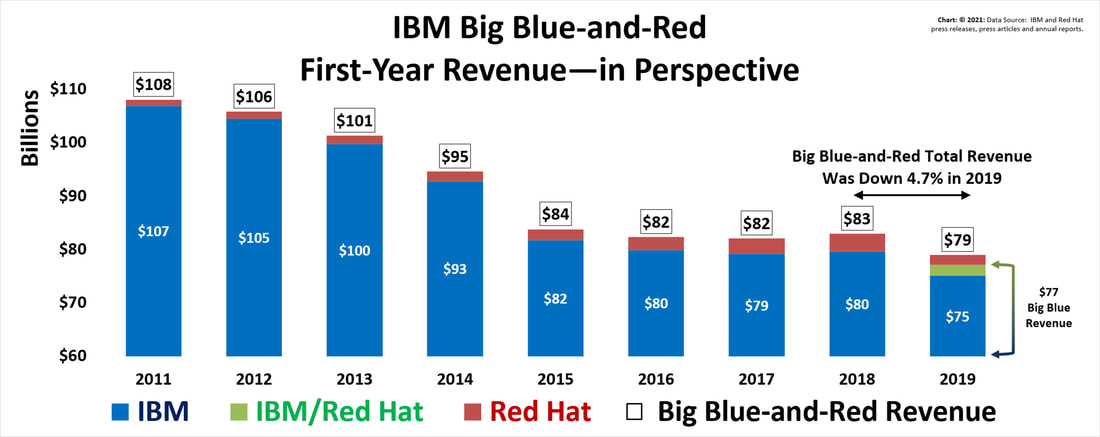

Even with Red Hat, last year’s revenue fell by 3.1%, and since Ginni took charge in 2012, revenue is down by 27.8%. (Remember that fictional million-dollar-a-quarter company that generated an additional $780 last quarterly? Well, 2018’s full-year sales of $4 million would have dropped by $124,000, and since the end of 2012, yearly sales would have dropped from $5,540,000. This makes it hard to get excited about $780, doesn’t it?)

With this perspective, here is Virginia M. Rometty's revenue record.

With this perspective, here is Virginia M. Rometty's revenue record.

Revenue has declined from $107 billion to $77 billion. This is a catastrophic revenue drop of almost 28%—despite sixty-three acquisitions in her first eighty-four months (Red Hat was number 64).

Obviously, sales didn't profit from these small acquisitions.

Obviously, sales didn't profit from these small acquisitions.

How Has IBM Historically Produced Stable, Growing Revenue?

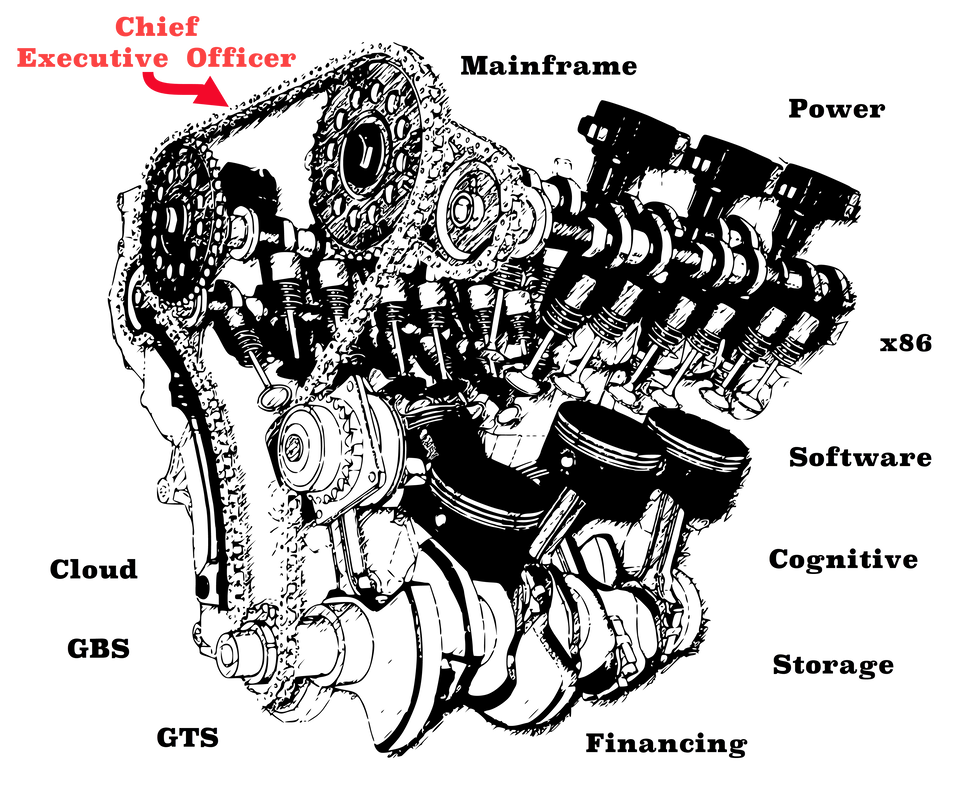

Reading the chief financial officer’s comments and the questions of the analysts, I thought how easy it is to get lost in all of IBM’s moving parts, and the chief financial officer was all about reviewing the revenue engine’s piece parts: Systems (mainframe, power and storage), Cloud & Cognitive, Global Business Services, and Global Technology Services. The whole discussion failed to answer a simple question: “Overall, how is the corporation doing?”

|

IBM has always been a multitude of linked, dependent, development organizations. They must work together like the pistons in the engine of a car in order to provide stable, growing revenue and profitability. Individual development organizations, along with their supportive sales organizations, like a piston, take “breathers.” On a “down stroke” they pull in a new charge of gas mixed with air and then compress the mixture awaiting a timely ignition.

Each organization takes in its customers’ requirements (gas), combines it with competitive development ingenuity (air) and then releases a product update for marketing and sales to ignite (ignition) … all of this looks pretty ugly in operation across multiple organizations, but when coordinated and working in cooperation with each other, they accomplish an amazing task: they transfer continuous, on-going power (revenue) to a transmission which can then be geared to drive slow or fast given the economic terrain to maintain a sustained movement in a strategic direction. |

The chief executive officer is the "timing chain" that ensures a balanced performance between independent, cooperative organizations: coordinated decentralization.

|

IBM over its 100+ year history has been, figuratively speaking, three-, four-, six- and eight-cylinder engines. Today, it is in a worse position than being a one-cylinder engine. It is a multi-cylinder engine which is misfiring. Not only are the organizations not helping each other, but they impede the corporations overall growth because finance—although it has abandoned the long-term, earnings per share roadmaps—is now focused on short-term, earnings-per-share targets. This constantly throttles back the amount of investment dollars available to all organizations. Starved for investment dollars, they misfire at the most inopportune times. All of this works against the efficiency of the revenue engine.

IBM misfires because its financial autocracy is starving the entire organization of investment funds, and its right arm—the human resources organization—is either demotivating and driving its best people out of the organization or failing to retain them. In fact, a Master Inventor left the corporation on the day of the analysts' call [here].

This makes the corporation inefficient, ineffective and unpredictable in revenue production; and there is no easy fix that will be found in one quarter’s microscopic revenue growth.

So, understanding this, how is the IBM revenue engine performing?

IBM misfires because its financial autocracy is starving the entire organization of investment funds, and its right arm—the human resources organization—is either demotivating and driving its best people out of the organization or failing to retain them. In fact, a Master Inventor left the corporation on the day of the analysts' call [here].

This makes the corporation inefficient, ineffective and unpredictable in revenue production; and there is no easy fix that will be found in one quarter’s microscopic revenue growth.

So, understanding this, how is the IBM revenue engine performing?

What Is the Revenue Big Picture?

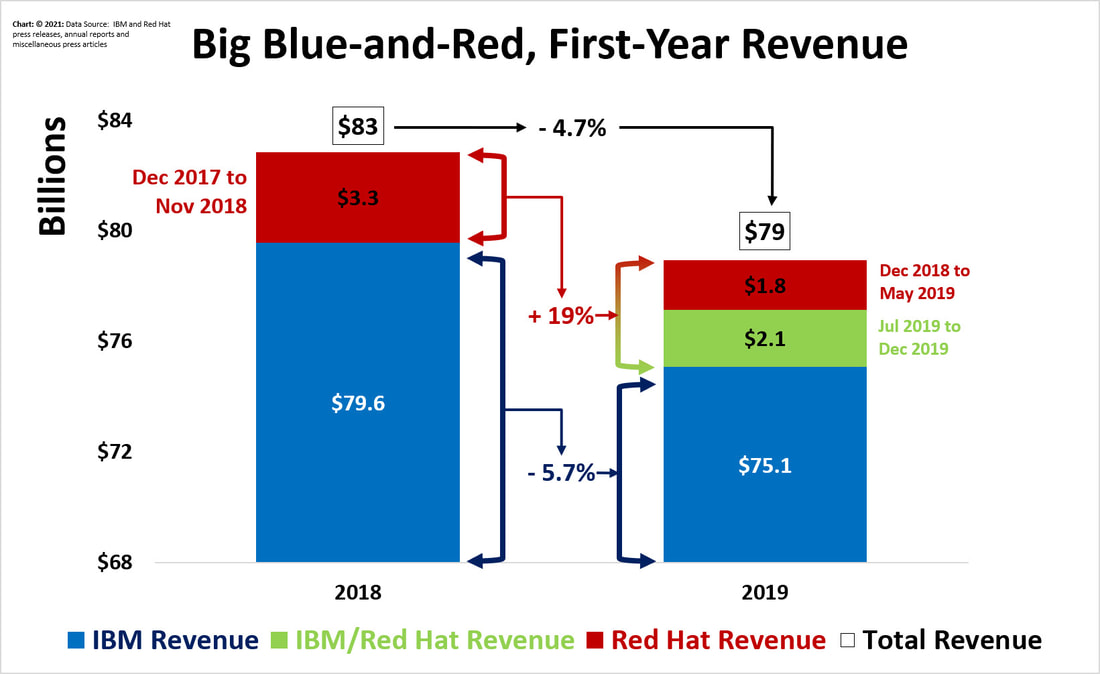

After reading the transcript of the analysts’ call, I wondered, “What is the big picture here?” It seemed logical to start with a baseline measurement: capture how IBM and Red Hat performed when they were still separate organizations in 2018. This baseline number could be used to measure the merits of this acquisition in future years. It seems logical that if IBM’s total revenue in future years (which will now include all Red Hat revenue) is significantly less than this baseline, it would be hard—with a straight face—to call the merger a success.

This simple measurement would cut through all the movement of the various corporate piece parts within the company and answer one basic question: How are IBM and Red Hat doing as a combined organization? Doesn’t it seem logical and appropriate that a $34 billion acquisition by a $80 billion dollar company should answer such a simple question clearly?

This simple measurement would cut through all the movement of the various corporate piece parts within the company and answer one basic question: How are IBM and Red Hat doing as a combined organization? Doesn’t it seem logical and appropriate that a $34 billion acquisition by a $80 billion dollar company should answer such a simple question clearly?

|

This chart shows IBM’s and Red Hat’s combined revenue in 2018 and 2019.

In red, is Red Hat’s revenue in 2018 and the first half of 2019—when it was independent of IBM. In green, is Red Hat’s revenue in the second half of 2019—as reported by IBM. In blue, is IBM’s core revenue—Big Blue revenue less Red Hat revenue. The critical observation is that IBM + Red Hat’s total combined 2019 revenue (blue + green + red) fell by almost $4 billion from 2018. |

After spending $35.1 billion for a comparatively tiny corporation that was supposed to save IBM, this is a financial hand grenade. Being off by even a billion will make little difference if the trend continues into 2020. [See Footnote]

The clue to this fall, was presumably contained in one sentence, but since IBM’s chief financial officer seems to rarely offer specific details, we will make some detailed assumptions.

The clue to this fall, was presumably contained in one sentence, but since IBM’s chief financial officer seems to rarely offer specific details, we will make some detailed assumptions.

IBM Isn't Firing on all Cylinders

Optimistically, the chief financial officer said that IBM’s mainframe sales were up “a strong 63%” and that the corporation experienced the “highest MIPs in history this quarter, driven by growth in new workloads.”

In the past, a 63% increase in quarterly mainframe sales and a new quarterly record in additional MIPs would have literally blown IBM’s revenue and profit numbers out of the water … if the revenue engine were firing on all cylinders.

In the past, a 63% increase in quarterly mainframe sales and a new quarterly record in additional MIPs would have literally blown IBM’s revenue and profit numbers out of the water … if the revenue engine were firing on all cylinders.

Comparing the end of year quarterly results for 2018 and 2019 doesn’t reveal any drastic increase in revenue as would be expected. [An excellent overview of Systems Group performance and Power Systems in particular is Timothy Morgan's "Power9 Enters the Long Tail."]

The chief financial officer noted that, “Growth in IBM z and Storage was mitigated by a decline in Power.” From the charts above, “mitigated” seems to be a very diplomatic choice of words. IBM needs to put it together across the entire corporation. It must start firing on all cylinders. A large diverse corporation such as IBM requires that every organization be staffed with engaged, passionate and enthusiastic product, brand and marketing managers, salesmen, technical-sales, service and support, developers and architects who are coordinated, supported and rewarded by the best of executive leadership at all levels of the organization.

This is the responsibility of the chief executive officer of the corporation, and she has failed.

And economic failure, as IBM has proven in the past, can come quickly.

The chief financial officer noted that, “Growth in IBM z and Storage was mitigated by a decline in Power.” From the charts above, “mitigated” seems to be a very diplomatic choice of words. IBM needs to put it together across the entire corporation. It must start firing on all cylinders. A large diverse corporation such as IBM requires that every organization be staffed with engaged, passionate and enthusiastic product, brand and marketing managers, salesmen, technical-sales, service and support, developers and architects who are coordinated, supported and rewarded by the best of executive leadership at all levels of the organization.

This is the responsibility of the chief executive officer of the corporation, and she has failed.

And economic failure, as IBM has proven in the past, can come quickly.

Three Decades Ago, IBM Fell in a Hurry

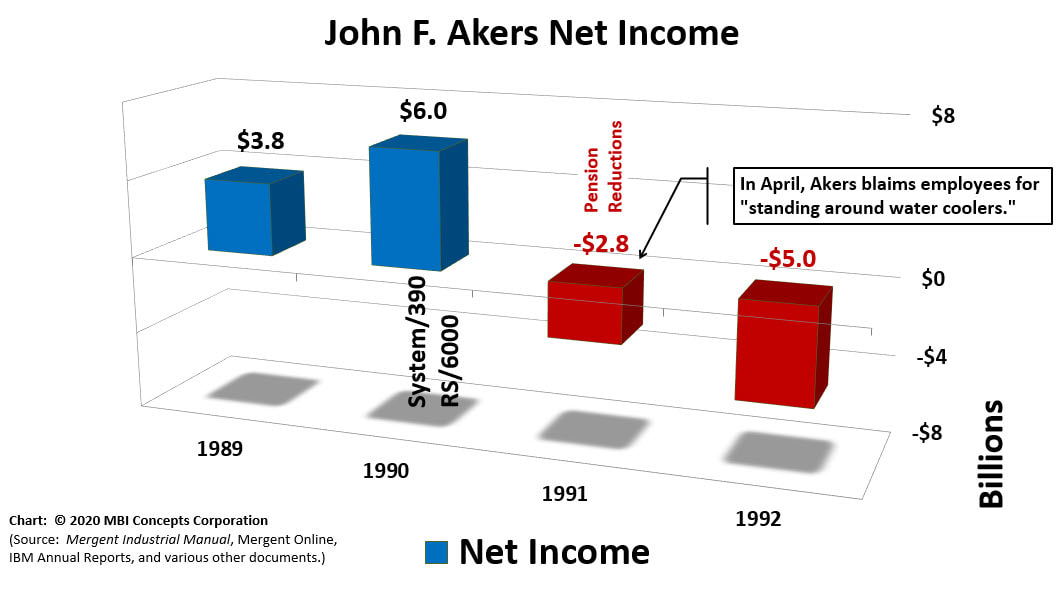

|

For those who believe that IBM’s profitability is too great to result in the corporation being pushed to the edge of bankruptcy any time soon, consider the chart to the right.

At the beginning of another decade (1990), IBM shipped the System/390 which was arguably a more significant upgrade to a much larger and more loyal mainframe install base than enjoyed by today’s IBM z15. The following years should have been years of plenty, but the corporation swung in one year from a $6 billion profit (the third highest net income in the history of the company to that point) to a $3 billion loss in 1991, a $5 billion loss in 1992, and then an $8 billion loss in 1993. |

Even with the shipment of the System/390 and the RS/6000 in 1990 IBM's net earnings plunged in 1991

|

John Akers for all his mistakes made the most crucial error of his career when he accused his fellow IBMers in 1991 of “standing around water coolers.” By 1992, most everyone had discerned that the corner office was the problem, not its people. This pales in comparison to what Virginia M. Rometty has done to her fellow IBMers through 401(k) modifications, resource actions, and personal/performance improvement plan (PIP) modifications [the latter of which is proving highly effective in trimming the sales organization through assignment of unattainable sales quotas] .

IBM’s most valuable resource, its human assets, are no longer tied to long-term pension plans. There are better benefits, higher pay, and actual job security elsewhere in the industry, and the loyalty of the individual to the corporation is not on par with what it was during the crisis of 1992-93.

IBM’s most valuable resource, its human assets, are no longer tied to long-term pension plans. There are better benefits, higher pay, and actual job security elsewhere in the industry, and the loyalty of the individual to the corporation is not on par with what it was during the crisis of 1992-93.

Author's Opinion: Falling Revenue is a Symptom of Bigger Issues

|

After the analysts' call, IBM stock climbed from 139.09 to 144.89, only to close at 138.62 on Jan 27—four trading days later.

|

No one can predict the future—either next quarter or next year—but the revenue tea leaves the Wall Street analysts are reading in the bottom of their teacups do not justify an optimistic outlook.

A speculator might take the odds that IBM will have another quarter of growth [which it failed to do in the first quarter of 2020]. A speculator might even take the odds that Wall Street will once again set its expectations so low that IBM can send its stock higher—for a few days—with another .078125% "spike" in quarterly revenue. After all, this is Wall Street. Speculators can print money whether the stock goes up or down. Employees have a much different perspective, and so should their chief executive. |

We will see if Arvind Krishna has a new perspective on what is wrong with IBM [He doesn't]. He will have to fix two decades of declining sales productivity and that will not be easy because IBM’s problem is a human relations problem.

Until IBM has multiple quarters or even multiple years of significant back-to-back revenue growth—it isn’t back. Especially when I have seen one of the largest migrations of individuals from IBM in a long time. Very good people are not only still being cut loose by the corporation to fund the on-going earnings-per-share beast, but now, very good people are leaving of their own accord. It appears that many individuals planned their exits around IBM’s archaic 401(k) vesting rules and are now moving on to other jobs (to get IBM's matching dollars each year you can't leave IBM for any reason other than retirement before December 15 of each year).

Unfortunately, there are more and bigger problems than revenue growth—the focus of this article. There are a slew of other problems lurking on the horizon: coming goodwill impairments, an increasingly negative, shareholder-equity-less-goodwill, and the on-going lack of employee engagement, passion and enthusiasm.

Cheers

Pete

Until IBM has multiple quarters or even multiple years of significant back-to-back revenue growth—it isn’t back. Especially when I have seen one of the largest migrations of individuals from IBM in a long time. Very good people are not only still being cut loose by the corporation to fund the on-going earnings-per-share beast, but now, very good people are leaving of their own accord. It appears that many individuals planned their exits around IBM’s archaic 401(k) vesting rules and are now moving on to other jobs (to get IBM's matching dollars each year you can't leave IBM for any reason other than retirement before December 15 of each year).

Unfortunately, there are more and bigger problems than revenue growth—the focus of this article. There are a slew of other problems lurking on the horizon: coming goodwill impairments, an increasingly negative, shareholder-equity-less-goodwill, and the on-going lack of employee engagement, passion and enthusiasm.

Cheers

Pete

[Footnote] In order to produce these charts, the author avoided letting perfection prevent the presentation of good enough. Red Hat’s fiscal year ended in February of each year. This presented difficulties aligning year-to-year revenue from the two corporation’s quarterly reports. The author believes that the way the data is presented in this chart, even though it omits Red Hat revenue for June 2019, actually shows a best-case scenario for IBM since December 2018 is included in the 2019 revenue numbers. Perfection would be to have monthly revenue numbers for Red Hat, but these numbers are not available unless IBM decides to provide them.