A Second Look at J. Ogden Armour's "The Packers"

|

|

Date Published: December 26, 2020

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

Ida M. Tarbell wrote of one of the luxuries she remembered that is applicable to this set of articles about packers and private-car lines: She remembered when a fresh orange was a “luxury for Christmas and birthdays.” By 1939, it was considered commonplace. We have come a long way. May we constantly sit together, talk and work to make possible what Miss Tarbell described as “Humanity’s Upward Spiral.”

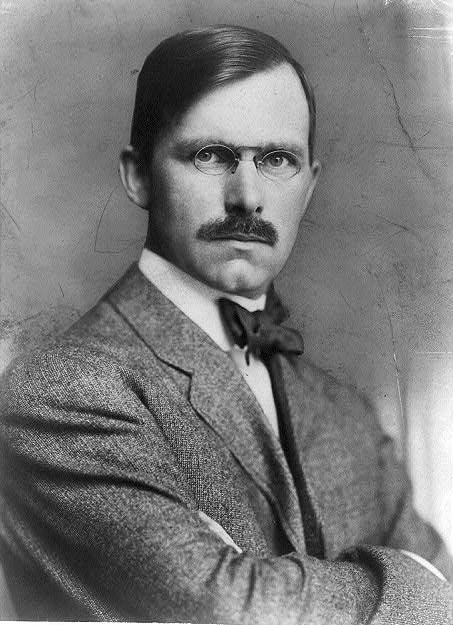

Ray Stannard Baker’s works, in my opinion, stand next to Ida M. Tarbell's in quality, thoroughness and frankness. They were a dynamic duo that represented the great American, conscientious journalists of the early 20th Century.

We need more today.

Ray Stannard Baker’s works, in my opinion, stand next to Ida M. Tarbell's in quality, thoroughness and frankness. They were a dynamic duo that represented the great American, conscientious journalists of the early 20th Century.

We need more today.

Taking a Second Look at a First Review of "The Packers"

Ray Stannard Baker's "The Rest of the Story"

|

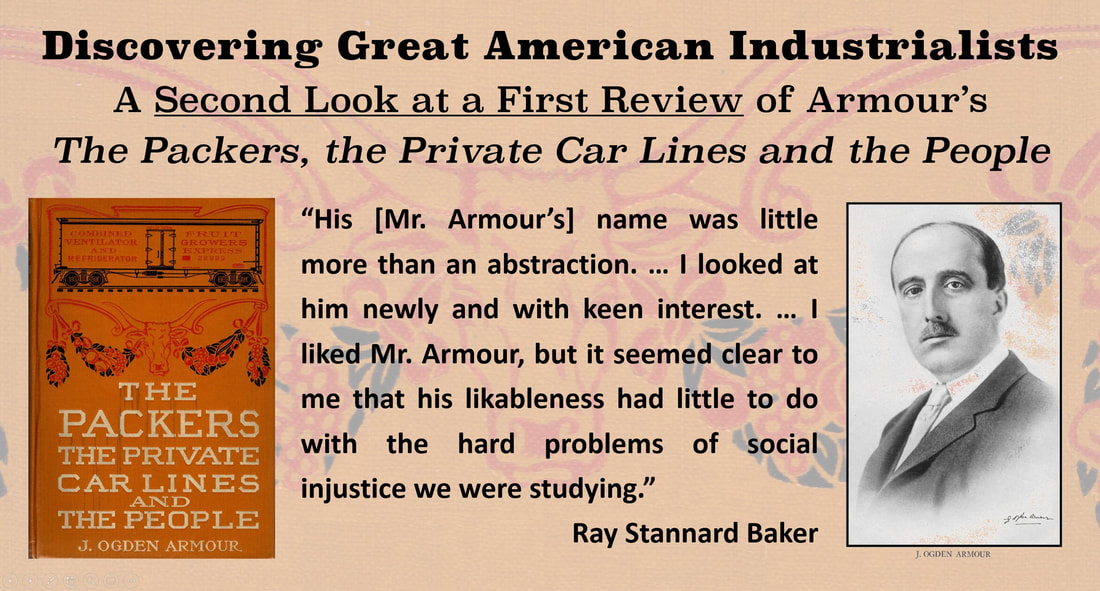

Ray Stannard Baker in his autobiography, American Chronicle, expands on his McClure's Magazine articles on the railroad and packer industries. I discuss these in my initial review of J. Ogden Armour’s The Packers, the Private Car Lines and the People. This is a “Second Look at a First Review.”

In my first review, I questioned the resistance humans have to sitting “together around a table and just talking to resolve our differences.” I wondered why Mr. Baker and Mr. Armour just never “sat down” together. Although, it is never mentioned in the articles, it just doesn’t “feel” like they had any face-to-face discussions. As it turns out, my feeling was right, at least at the time of the publication of Mr. Armour’s book, but Baker and Armour did sit down together—after some of this “water had passed under the bridge.” Since I have not yet read the full work of Stannard Baker but only accessed the few pages about J. Ogden Armour, I have no overall review of his work. I am including snippets here that document these two grown men did have a heart to heart discussion. |

It is heart warming and although no final agreed to solution was reached, it is obvious that both arrived at a better understanding of each other’s positions. Isn’t that how we grow as human beings? Doesn’t it take time?

Ray Stannard Baker starts off talking about his next article in response to J. Ogden Armour’s release of his book: The Packers.

Ray Stannard Baker starts off talking about his next article in response to J. Ogden Armour’s release of his book: The Packers.

“I had been charged with seeing only one side of the case, but I had not failed [in his previous articles] to consult the Armour people while I was making my preliminary inquiry, and I now went to see them again. In fact Mr. Armour himself invited me to come. I had several long talks with him. . . .

“In writing my railroad articles I had scarcely given any thought to Mr. Armour personally. His name was little more than an abstraction which had come to express a huge industrial and commercial machine which, in some of its operations, seemed to me to be inimical to the public good. I imagine that to most people of that period the names of Armour, Swift or even Rockefeller and Morgan were more or less abstractions. When I first talked with Mr. Armour's associates, they said to me:

“If you had known Mr. Armour personally, you would not have written as you have.” [This supports and supplies credibility to B. C. Forbes’ 1917 observation of Mr. Armour in "The Men Who Are Making America."]

“No, I should not—quite. I should have seen more clearly the human side of the problems. In discussing cold economic questions or in condemning what seems socially wrong, it is disturbing to feel that the man who represents the things which we look upon as evil will go home at night to his children, that he has friends who love him, that he is not an abstract force, but a mere man like the rest of us. In our judgments we constantly forget this personal equation unless we know the man, and then we are likely to overemphasize it.

“What happened there in that Chicago office was that Mr. Armour came alive to me as a human being. I was surprised to find him engagingly direct. … I found that Armour had reasons enough for his course. Armour was perfectly logical. I thought that if he could get down among us—but he couldn’t and that was the pity of it—we should all like him. I did.

“I looked at him newly and with keen interest. . . . Well I liked Mr. Armour, but it seemed clear to me that his likableness had little to do with the hard problems of social injustice we were studying.”

“In writing my railroad articles I had scarcely given any thought to Mr. Armour personally. His name was little more than an abstraction which had come to express a huge industrial and commercial machine which, in some of its operations, seemed to me to be inimical to the public good. I imagine that to most people of that period the names of Armour, Swift or even Rockefeller and Morgan were more or less abstractions. When I first talked with Mr. Armour's associates, they said to me:

“If you had known Mr. Armour personally, you would not have written as you have.” [This supports and supplies credibility to B. C. Forbes’ 1917 observation of Mr. Armour in "The Men Who Are Making America."]

“No, I should not—quite. I should have seen more clearly the human side of the problems. In discussing cold economic questions or in condemning what seems socially wrong, it is disturbing to feel that the man who represents the things which we look upon as evil will go home at night to his children, that he has friends who love him, that he is not an abstract force, but a mere man like the rest of us. In our judgments we constantly forget this personal equation unless we know the man, and then we are likely to overemphasize it.

“What happened there in that Chicago office was that Mr. Armour came alive to me as a human being. I was surprised to find him engagingly direct. … I found that Armour had reasons enough for his course. Armour was perfectly logical. I thought that if he could get down among us—but he couldn’t and that was the pity of it—we should all like him. I did.

“I looked at him newly and with keen interest. . . . Well I liked Mr. Armour, but it seemed clear to me that his likableness had little to do with the hard problems of social injustice we were studying.”

Ray Stannard Baker, American Chronicle, 1945

Ray Stannard Baker put all of these observations into his next article. He felt that he now “presented all phases of the situation more clearly than ever before.” The article, though, was never published. McClures’ Magazine was in a state of “disintegration.” This is well documented in Ida M. Tarbell’s autobiography also.

Maybe someday, someone will be digging through the papers of Ray Stannard Baker and send that article to me. I think it would reveal the thoughts of both men. Ray Stannard Baker appeared at times to be struggling to stop what he considered an evil phenomenon—the centralization and urbanization of America. Looking back on history, it was not a vain task to prevent the ills that were coming from it … but trying to stop the movement from rural to urban was in vain. The growth of “good trusts” or "good big businesses" eventually provided higher quality goods at ever lower prices so that men, women and their families could afford more “luxuries” each year than the year before. Such was Henry Ford’s automobile.

Ida M. Tarbell wrote of one of the luxuries she remembered that is applicable to this set of articles about packers and private-car lines: She remembered when a fresh orange was a “luxury for Christmas and birthdays.” By 1939, it was considered commonplace. We have come a long way. May we constantly sit together, talk and work to make possible what Miss Tarbell described as “Humanity’s Upward Spiral.”

I think when I am done with Ray Stannard Baker’s works, he will stand next to Ida M. Tarbell as one of America’s great, conscientious journalists.

We need more today.

Cheers,

- Pete

Maybe someday, someone will be digging through the papers of Ray Stannard Baker and send that article to me. I think it would reveal the thoughts of both men. Ray Stannard Baker appeared at times to be struggling to stop what he considered an evil phenomenon—the centralization and urbanization of America. Looking back on history, it was not a vain task to prevent the ills that were coming from it … but trying to stop the movement from rural to urban was in vain. The growth of “good trusts” or "good big businesses" eventually provided higher quality goods at ever lower prices so that men, women and their families could afford more “luxuries” each year than the year before. Such was Henry Ford’s automobile.

Ida M. Tarbell wrote of one of the luxuries she remembered that is applicable to this set of articles about packers and private-car lines: She remembered when a fresh orange was a “luxury for Christmas and birthdays.” By 1939, it was considered commonplace. We have come a long way. May we constantly sit together, talk and work to make possible what Miss Tarbell described as “Humanity’s Upward Spiral.”

I think when I am done with Ray Stannard Baker’s works, he will stand next to Ida M. Tarbell as one of America’s great, conscientious journalists.

We need more today.

Cheers,

- Pete