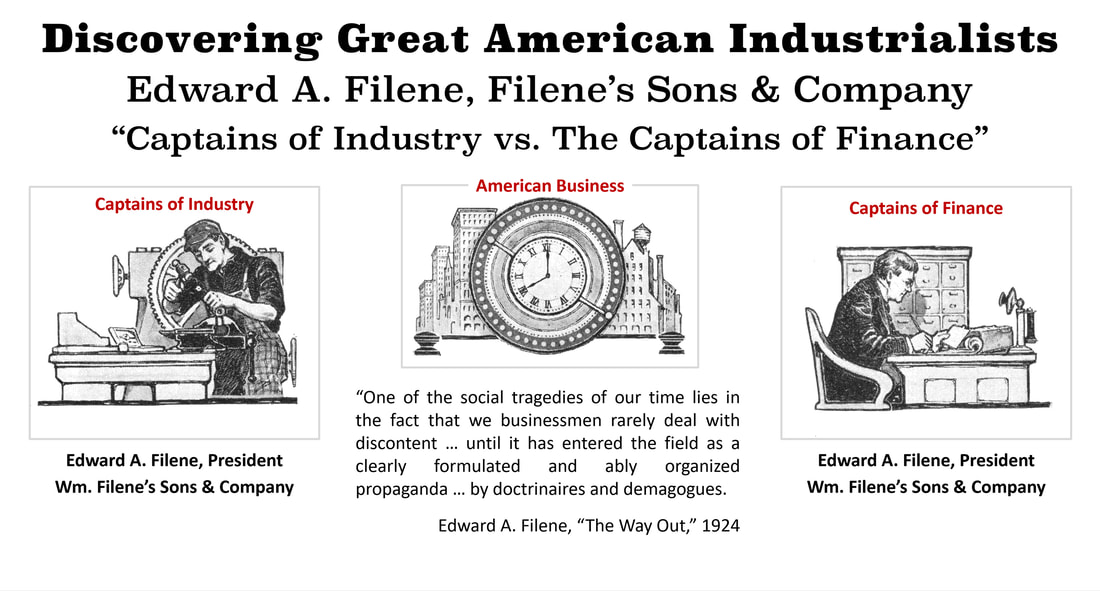

Captains of Industry vs. Captains of Finance

|

|

Date Published: October 21, 2022

Date Modified: October 19, 2023 |

A reader would be hard pressed to believe that the concepts expressed in this article are from the beginning of the 20th Century rather than the 21st Century. Some minor edits have been made on this article, and headings, subheadings and images have been added to make this 100-year-old article "feel" more current and improve readability.

It is hoped that these changes will help overcome some pre-conceived notions about the currency of Edward A. Filene's proposition that the economic system of capitalism needs more industrialists, more entrepreneurs, and more "capitalists" who are motivated by the right principles.

It is hoped that these changes will help overcome some pre-conceived notions about the currency of Edward A. Filene's proposition that the economic system of capitalism needs more industrialists, more entrepreneurs, and more "capitalists" who are motivated by the right principles.

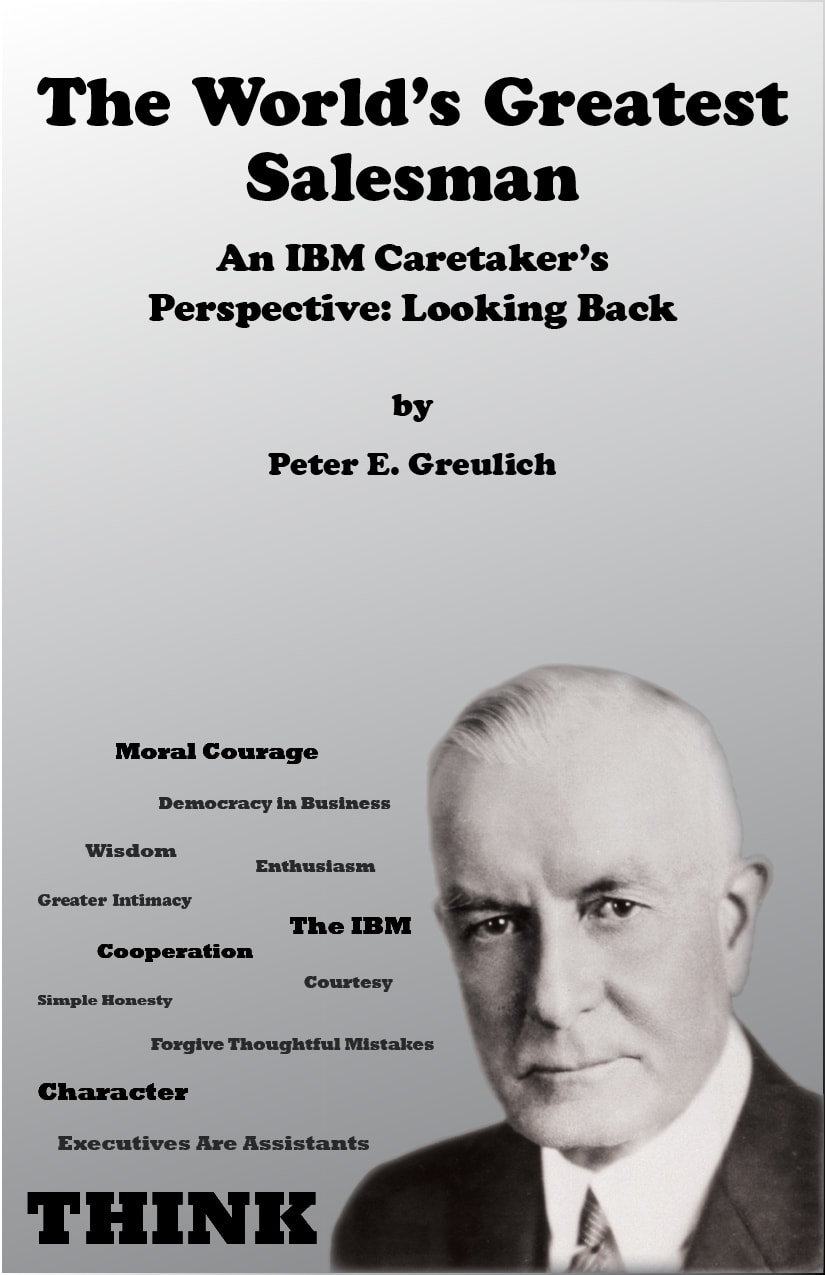

Peter E. Greulich, Author and Public Speaker

Captains of Industry vs. Captains of Finance

- The Moral Obligation of the Businessman

- A Legitimate, Moral Discontent of the Oppressed Is the Root of Revolutions

- An Example of Industrialist Thinking vs. Capitalist Thinking

- Filene’s Summary of His Contrasting Viewpoints

- This Author’s Thoughts on Edward A. Filene’s Article

|

Behind most of the extreme and ill-considered revolts of our time there is a grain of truth, some legitimate ground for protest which has too long been ignored by the those whose hands are on the levers of power and authority.

This bit of truth, in the hands of reckless doctrinaires, is inflated into a dangerous falsehood and made the inspiration of a radical propaganda which, now and then, flames into actual revolution. Revolutions never spring from pure theory. Widespread discontents are never born of the imagination alone. They may be fed and fanned by designing theorists. They may be harnessed to utterly indefensible programs by able demagogues, but usually they have their beginning in some legitimate protest. There are usually three stages in the development of revolutions.

|

This article was published in Edward Filene’s “The Way Out.” Select image to read a review.

|

- The second stage is marked by the moral discontent of the oppressed: the legitimate protest of those upon whom the status quo rests heavily.

- The third stage is frequently marked—although not always, by an immoral discontent propagated by demagogues: those who exploit the legitimate discontent of their time in the exclusive interest of themselves or their class.

|

Select to read Theodore Roosevelt's thoughts on finding the balance between individualism and socialism.

|

It seems to me that one of the social tragedies of our time lies in the fact that we rarely deal with discontent until it has reached this third stage, until it has entered the field as a clearly formulated and ably organized propaganda, and until it has been captured by doctrinaires and demagogues.

In this tragedy, we business men must be classed among the chief sinners. We should, if we were really good business men and not mere tradesmen, anticipate most of the unrest of our time.

|

We should, if we really met the challenge of our jobs, forestall most revolutionary movements by rendering it increasingly difficult for revolutionary leaders to find a sympathetic audience. We businessmen should remove the causes of society’s legitimate, moral discontent to disarm the demagogues’ and doctrinaires’ propagation of immoral discontent.

The Moral Obligation of the Businessman

|

We are directors in the field of economic activity from which most discontents and revolutions arise. It is our business to see to it that in this field there is no soil in which mutiny can take root.

This is not a “social welfare” chore to be undertaken after office hours as evidence of our “public spirit,” but one of our primary business responsibilities. If, as business men, we cannot or will not meet this responsibility, we deserve to see our leadership in economic activity superseded—it shall be superseded. I am not leading up to a suggestion that we business men should align ourselves with all sorts of anti-radical propaganda. |

Select to read this author’s article on capitalist and industrialist leadership.

|

It is the easiest thing in the world, a thing demanding little imagination—and less intelligence, to wait until the world is rocking with revolution and then to rush hysterically to the support of superficially conceived and essentially futile “anti-Bolshevik” propagandas. It is as useless as it is easy to swear at the results of radicalism.

Our more difficult but fundamental obligation is to remove the incentives to radicalism.

It is the cause rather than the effect that should be our chief concern.

It is the cause rather than the effect that should be our chief concern.

We business men pride ourselves upon our ability to think clearly from cause to effect when the financial interests of our businesses are involved. We should be heartily ashamed when we fail to think with equal clarity from cause to effect about the wider social implications of our businesses. We should realize that, in times of threatening unrest and revolutionary agitation, adventures in “professional patriotism” are not a valid substitute for business statesmanship.

The time to defeat a revolution is before it starts. It is shortsighted to wait until a revolution has reached the “terror” stage before we take notice of it. We must deal with it in its “germ” stage. This means that the business man must be more alert than the radical in sensing those legitimate grounds for protest which, as I have suggested, are usually the points of departure for the dangerous activity of the doctrinaire revolutionist. We must, as a simple business duty, deal with the causes of radicalism earlier and more efficiently than the radical leaders do.

It is not, however, a mere opportunism that I am suggesting. I am not suggesting merely a better way of guarding the bank. I am discussing this challenge that radicalism means to business as one aspect of a larger plea for the introduction of the scientific spirit into the administration of business and industry.

I am suggesting that we must parallel the achievements of preventive medicine with the achievements of preventive economics.

Let me illustrate what I mean by business men anticipating revolutions.

The time to defeat a revolution is before it starts. It is shortsighted to wait until a revolution has reached the “terror” stage before we take notice of it. We must deal with it in its “germ” stage. This means that the business man must be more alert than the radical in sensing those legitimate grounds for protest which, as I have suggested, are usually the points of departure for the dangerous activity of the doctrinaire revolutionist. We must, as a simple business duty, deal with the causes of radicalism earlier and more efficiently than the radical leaders do.

It is not, however, a mere opportunism that I am suggesting. I am not suggesting merely a better way of guarding the bank. I am discussing this challenge that radicalism means to business as one aspect of a larger plea for the introduction of the scientific spirit into the administration of business and industry.

I am suggesting that we must parallel the achievements of preventive medicine with the achievements of preventive economics.

Let me illustrate what I mean by business men anticipating revolutions.

- How Revolutions Take Root

|

There is abroad in the world today [1917–25] a revolt against the modern business system and against that free individualism which most of us—even when most aware of its sins—believe must always be the dynamo of any truly creative and happy society.

This revolt finds its extreme expression in the proposed dictatorship of the proletariat. The tools of the world should belong to the men who use them, say the leaders of this revolt. … They want to rid the world of the practice of paying men for “owning” things, and to organize a society in which men shall be paid only for “doing” things. … These are the general principles that lie back of the slogans of this revolt. |

I am not here concerned with the futuristic political schemes that are offered as means of attaining these ends, but only with these simple statements of principle—or catchwords, if you prefer—which the leaders of this revolt have preached to the masses, and with the reasons why the masses were so ripely ready to listen to them and so easily inflamed by them.

Here is a revolt that has reached its third stage, a revolt that is keeping business men awake nights the world over. What, if we are scientifically minded business men, will be our attitude toward it? What could we have done to anticipate and to discount it?

Too many of us, I fear, think we have discharged our duty in the matter when we have written an article or made a speech attacking the unsound economics of the revolutionist. We may subject the revolutionist’s interpretation of his catchwords to all sorts of valid criticism. We may rightly challenge the notion that the proletarian workman is the only creator of wealth in the economic process.

We may rightly protest against the wholesale indictment of the men who own things. There are brain-workers as well as brawn-workers. We may rightly insist that the men who contribute “the toil of their ideas” to industry are creators of wealth as well as the men who contribute “the toil of their hands.”

But the point I should like to emphasize is that it is now too late to meet this revolt with mere argument. Fifty years ago, we business men should have been dealing with the germ of this revolt, with those legitimate criticisms of our business and social order that were the soil in which this revolt took root. And it does not seem to me that any particular clairvoyancy was needed to see it.

Now I do not mean to suggest that the present revolutionary movement could have been completely prevented by business men alone. Social issues are not as simple as all that. Harmonious social advance is never the fruit of the cleverness of a single group, but the net result of a wise collaboration of statesmen, businessmen, labour leaders, scientists, and educationalists … of all the men who stand in key positions, determining the purpose and administering the power of society.

But I do mean to suggest, as one of the most firmly established convictions of my life, that the revolutionists would have had a vastly more difficult time getting a hearing from the masses if, for the last fifty years, we business men of the United States, England, Italy, France, Germany, and Russia had been thinking constantly and clearly about some of the neglected issues of business and industry.

By neglected issues of business and industry, I mean some of the issues which, despite the fact that they underlie the whole future of our businesses, have been given scant attention because their immediate relation to the year’s balance sheet was not obvious.

Here is a revolt that has reached its third stage, a revolt that is keeping business men awake nights the world over. What, if we are scientifically minded business men, will be our attitude toward it? What could we have done to anticipate and to discount it?

Too many of us, I fear, think we have discharged our duty in the matter when we have written an article or made a speech attacking the unsound economics of the revolutionist. We may subject the revolutionist’s interpretation of his catchwords to all sorts of valid criticism. We may rightly challenge the notion that the proletarian workman is the only creator of wealth in the economic process.

We may rightly protest against the wholesale indictment of the men who own things. There are brain-workers as well as brawn-workers. We may rightly insist that the men who contribute “the toil of their ideas” to industry are creators of wealth as well as the men who contribute “the toil of their hands.”

But the point I should like to emphasize is that it is now too late to meet this revolt with mere argument. Fifty years ago, we business men should have been dealing with the germ of this revolt, with those legitimate criticisms of our business and social order that were the soil in which this revolt took root. And it does not seem to me that any particular clairvoyancy was needed to see it.

Now I do not mean to suggest that the present revolutionary movement could have been completely prevented by business men alone. Social issues are not as simple as all that. Harmonious social advance is never the fruit of the cleverness of a single group, but the net result of a wise collaboration of statesmen, businessmen, labour leaders, scientists, and educationalists … of all the men who stand in key positions, determining the purpose and administering the power of society.

But I do mean to suggest, as one of the most firmly established convictions of my life, that the revolutionists would have had a vastly more difficult time getting a hearing from the masses if, for the last fifty years, we business men of the United States, England, Italy, France, Germany, and Russia had been thinking constantly and clearly about some of the neglected issues of business and industry.

By neglected issues of business and industry, I mean some of the issues which, despite the fact that they underlie the whole future of our businesses, have been given scant attention because their immediate relation to the year’s balance sheet was not obvious.

An Example: Long-Term, Industrialist Thinking vs. Short-Term, Capitalist Thinking

|

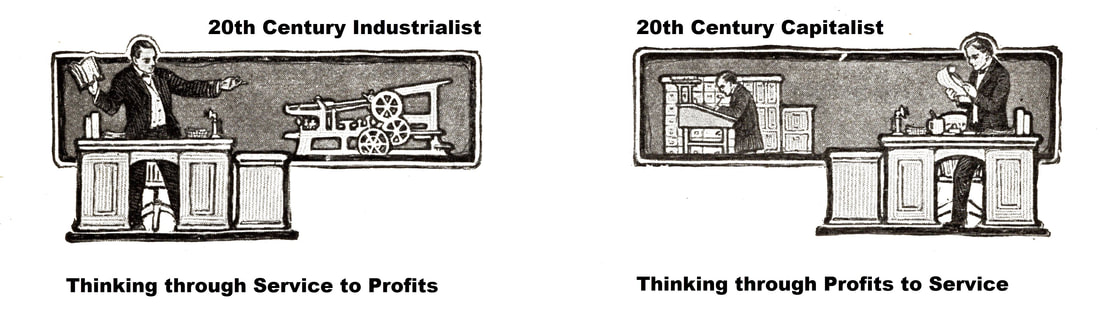

The relative authority and influence of the industrialist and the capitalist points of view in business is another neglected issue, and one that I may well use to illustrate the contention of this chapter, for I think it is true to say that the slow and, to my mind, often sinister encroachment of the capitalist upon the industrialist point of view in business has given the modern revolutionist one of their best arguments.

It is not by accident that the radical agitator attacks the great capitalist more often than he attacks the great industrialist. It is because there frequently is, although there should never be, a basic difference between the capitalist and the industrialist approach to the problems of business and industry. Since illustration always lingers longer in the mind than exposition, let me suggest a hypothetical case, based upon numerous instances that have caught my attention, that will indicate what seems to me to be the frequent antagonism between these two points of view. |

- An Industrialist through Service Builds Something to Last

|

An industrialist building a business based on service.

|

Jim Restaurateur is the able and ambitious proprietor of a single restaurant. Not content with his limited activities, he dreams of himself as the entrepreneur and industrialist of a great chain of restaurants stretching across the continent. He is animated by a very definite ideal. He purposes to create a chain of restaurants that will sell wholesome food, cooked in sanitary kitchens, and served in clean and attractive dining rooms at the lowest possible prices.

He is an individual who sees the wide social usefulness of such an application of the principles of mass production and mass distribution, but a man who also realizes, that in carrying out such a program successfully, he will be not only a great benefactor but a good business man. |

He sets about the realization of his dream.

He builds slowly, making each expansion justify itself by patronage won and profits made. He gives the best years of his life to the project. He succeeds. Finally, the cheerful fronts of his restaurants may be seen on the streets of most of our cities.

He builds slowly, making each expansion justify itself by patronage won and profits made. He gives the best years of his life to the project. He succeeds. Finally, the cheerful fronts of his restaurants may be seen on the streets of most of our cities.

|

His interests stretch far beyond the walls of his restaurants. He has, in his ceaseless endeavor to eliminate every needless expense between producer and consumer, become the owner of great farms and dairy herds that supply his tables.

He has, by making wholesome food available at low prices, protected the pocketbooks and preserved the health of a vast army of low- and medium-salaried folk. He has become a very wealthy man by performing a needed national service. A good social policy has once more proved a good business policy. Now all through this adventure, stretching over many years, Jim Restaurateur has brought to the administration of his chain of restaurants a genuinely creative enthusiasm, the spirit of the good craftsman, and the spirit, if I may say it, of the artist. |

Jim Restaurateur builds his business on service and full stores are the result of mass production.

|

The chain of restaurants has been his medium of self-expression as truly as the theatre was Shakespeare’s. [See Footnote #1]

He has, by selling wholesome food to the largest possible number at the lowest possible price—mass production, rendered his public service to his generation as truly as Andrew Carnegie rendered a public service to his generation by dotting the country with public libraries. The spectacular success of his enterprise the business man must not forget, has been due to the fact that Jim Restaurateur always thought from service through to profits, not from profits through to service. His restaurants have become a national institution supported by an enthusiastic and loyal clientele.

The “good will” value of his business is enormous. [See Footnote #2]

He has, by selling wholesome food to the largest possible number at the lowest possible price—mass production, rendered his public service to his generation as truly as Andrew Carnegie rendered a public service to his generation by dotting the country with public libraries. The spectacular success of his enterprise the business man must not forget, has been due to the fact that Jim Restaurateur always thought from service through to profits, not from profits through to service. His restaurants have become a national institution supported by an enthusiastic and loyal clientele.

The “good will” value of his business is enormous. [See Footnote #2]

- A Capitalist Extracts Quick and Large Profits but Loses Clientele

|

A capitalist—a financial investor, seeking quick profits.

|

But Jim Restaurateur is getting old or, at least, a little tired of the responsibilities of the industrialist. At this critical moment—and the tiredness of the creative entrepreneur is always a critical moment in a great business—he is approached by a syndicate of capitalists who offer him an extravagantly large amount for his business. They may ease his exit by making him an officer of the reorganized enterprise, but, when the transaction is closed, Jim Restaurateur is no longer the dominating spirit of the business.

We may now see what happens when the capitalist point of view replaces the industrialist point of view, and the business touches intimately the welfare of a great section of the consuming public.

|

The capitalist-owners of the chain of restaurants were attracted to the undertaking by the possibility of quick and large profits that might be made from a vigorous exploitation of the reputation and good will built up over the years by the dreams and deeds of Jim Restaurateur.

The chain of restaurants is not the “life work” of the capitalist-owners as it has been of Jim Restaurateur. It is only one of a long list of interests.

Now what happens as a result of this change in ownership?

A program of expansion is promptly set under way. The links in the chain of restaurants are multiplied rapidly month by month. The old ideals of simplicity and low prices figure less and less in the business. The dividends for the money paid for the good will of the business and the capitalists’ very large “organizing profits” must be provided.

The reputation and good will won by the industrialist point of view that thought from service through to profits are capitalized and exploited by the capitalist point of view that thinks from profits through to service.

Here and there certain restaurants in the chain are made fancier and more conventional, and the added overhead charge involved means a marked advance in prices. All the chain’s prices are advanced slightly from time to time. This means, in the aggregate, a handsome addition to the profits of the enterprise.

The new owners can carry on this policy of exploitation for a number of years before it begins to alienate the clientele built up by Jim Restaurateur, because the original service was so much above and the prices were so much below the prices of the average restaurant that there is a large margin of safety for change.

A long stretch of time may intervene before the public as a whole loses the confidence that was slowly won by Jim Restaurateur, but in this interval huge profits are extracted from the enterprise.

The chain of restaurants is not the “life work” of the capitalist-owners as it has been of Jim Restaurateur. It is only one of a long list of interests.

Now what happens as a result of this change in ownership?

A program of expansion is promptly set under way. The links in the chain of restaurants are multiplied rapidly month by month. The old ideals of simplicity and low prices figure less and less in the business. The dividends for the money paid for the good will of the business and the capitalists’ very large “organizing profits” must be provided.

The reputation and good will won by the industrialist point of view that thought from service through to profits are capitalized and exploited by the capitalist point of view that thinks from profits through to service.

Here and there certain restaurants in the chain are made fancier and more conventional, and the added overhead charge involved means a marked advance in prices. All the chain’s prices are advanced slightly from time to time. This means, in the aggregate, a handsome addition to the profits of the enterprise.

The new owners can carry on this policy of exploitation for a number of years before it begins to alienate the clientele built up by Jim Restaurateur, because the original service was so much above and the prices were so much below the prices of the average restaurant that there is a large margin of safety for change.

A long stretch of time may intervene before the public as a whole loses the confidence that was slowly won by Jim Restaurateur, but in this interval huge profits are extracted from the enterprise.

Ultimately the ideal of the industrialist—Jim Restaurateur, is lost.

|

The big chain of restaurants ceases to be a social asset and simply becomes a collection of conventional restaurants. The medium-salaried clerk who in the old days could get a decent meal for, say, forty cents, now finds that a really satisfactory dinner costs him perhaps a dollar.

Necessity forces him to turn elsewhere, and his going signals the beginning of the disintegration of the real usefulness of the business. The capitalist point of view has killed the goose that laid the golden egg, and the public must empty its pocketbook in high-priced restaurants or ruin its stomach with shoddy food while it waits for another Jim Restaurateur to appear on the scene. |

The new owners eventually alienate the old clientele as they prioritize profits over service—empty stores now proliferate.

|

I could multiply such hypothetical cases indefinitely or compile an imposing list of actual instances from the business history of our country. I could bring numerous instances to show how the substitution of the capitalist for the industrialist point of view affects good relations between employer and employees, and seriously hinders social progress.

It is not my purpose to write a text book on economics or to try my hand at muckraking. …

This single illustration serves to support my contention.

It is not my purpose to write a text book on economics or to try my hand at muckraking. …

This single illustration serves to support my contention.

- The Shortfalls of Short-Term Capitalist Thinking

It is clear beyond need of explanation that most of the sins for which the modern revolutionist indict our social system are sins of the capitalist point of view, not of the industrialist point of view.

By this indictment of the capitalist (financial) point of view, I do not mean a wholesale indictment of the banking fraternity. The capitalist point of view, one regrets to say, is too often found in the board of directors of business and industrial concerns no less than in the board of directors of banks.

Our whole business philosophy needs an overhauling to the end that the creative spirit of the industrialist may everywhere dominate our stores, our shops, our offices, our factories, and our banks. It is because the spirit of the industrialist has only hovered on the outskirts of our business and finance that we are today face to face with a frank revolt against the whole modern business system.

By this indictment of the capitalist (financial) point of view, I do not mean a wholesale indictment of the banking fraternity. The capitalist point of view, one regrets to say, is too often found in the board of directors of business and industrial concerns no less than in the board of directors of banks.

Our whole business philosophy needs an overhauling to the end that the creative spirit of the industrialist may everywhere dominate our stores, our shops, our offices, our factories, and our banks. It is because the spirit of the industrialist has only hovered on the outskirts of our business and finance that we are today face to face with a frank revolt against the whole modern business system.

|

Read how Henry Ford took on his board of director's "Shareholder-First and -Foremost" philosophy.

|

It may seem that I am wandering from economics into evangelism, but my quarrel with the capitalist point of view in business is not only that it courts revolt but that it is, in the long run, bad business.

The industrialist is a better patron saint for business than the sort of capitalist who thinks only in dividends. [Henry Ford had a board of directors and a shareholder community that was very capitalist driven—demanding dividends beyond reason. Read this article to see how Mr. Ford took his “capitalist” investors to school: Henry Ford Takes Control of His Business]. |

- The Importance of a Properly Functioning Capitalist Spirit

My contention, stated earlier in this book, that the best social policy is the best business policy is as sound for the capitalist as for the shopkeeper, and some of our best capitalists are already seeing this.

The task of the modern capitalist is not the simple and soulless task of the ancient money lender. They need more than a mere mastery of interest tables. They are, if I may steal a word from the arts, the impresarios of the productive abilities of society. In a very real sense, the capitalists control the team-work of mankind. Through the instrumentality of credit, they may combine the skill and knowledge of men for creative undertakings.

The administration of credit is one of the most important social powers in modern society. Credit is the life-blood of the business system which feeds and clothes and shelters mankind, and it is, therefore, a species of social treason not to regard its administration as a public responsibility and a creative opportunity.

The real rulers of modern society are not the men who own the most, but the men who exercise the most control over enterprise, namely, those who administer the world’s money.

The task of the modern capitalist is not the simple and soulless task of the ancient money lender. They need more than a mere mastery of interest tables. They are, if I may steal a word from the arts, the impresarios of the productive abilities of society. In a very real sense, the capitalists control the team-work of mankind. Through the instrumentality of credit, they may combine the skill and knowledge of men for creative undertakings.

The administration of credit is one of the most important social powers in modern society. Credit is the life-blood of the business system which feeds and clothes and shelters mankind, and it is, therefore, a species of social treason not to regard its administration as a public responsibility and a creative opportunity.

The real rulers of modern society are not the men who own the most, but the men who exercise the most control over enterprise, namely, those who administer the world’s money.

Filene's Summary of His Contrasting Viewpoints

By Edward A. Filene’s definition, individuals such as IBM's Thomas J. Watson Sr., Thomas J. Watson Jr., T. Vincent Learson, and Frank T. Cary were “Industrialist-driven,” while their successors such as John R. Opel, John F. Akers, Louis V. Gerstner, Samuel J. Palmisano, and Virginia M. Rometty, who were driven by the stock price, could be classified as “capitalist-driven.”

It is vital to the future of society, therefore, that the capitalist point of view become less and less exploitative and more and more creative. …

To go back to our illustration, one of the basic problems of our time is to bring the creative spirit of Jim Restaurateur into the syndicate of capitalists that buy his restaurants. It is, we must admit, harder for the capitalist/financier than for the industrialist/entrepreneur to maintain a sound social sense and act always from the motives of the industrialist rather than the motives of the money lender.

It is difficult for the capitalist to feel the thrill of creative effort because they are one step removed from the actual creative process. The industrialist sees their vast reclamation project realized under their hands. The capitalist who financed the project meanwhile is at their desk planning still other projects on paper.

To go back to our illustration, one of the basic problems of our time is to bring the creative spirit of Jim Restaurateur into the syndicate of capitalists that buy his restaurants. It is, we must admit, harder for the capitalist/financier than for the industrialist/entrepreneur to maintain a sound social sense and act always from the motives of the industrialist rather than the motives of the money lender.

It is difficult for the capitalist to feel the thrill of creative effort because they are one step removed from the actual creative process. The industrialist sees their vast reclamation project realized under their hands. The capitalist who financed the project meanwhile is at their desk planning still other projects on paper.

|

The shopkeeper/industrialist presides over a little “civilization” all their own as they go in and out among their hundreds or thousands of employees and watch the flow of customers through their store. It is all very human and very engaging to them.

But the banker who extends to him the credit that makes this business possible must meanwhile keep to the business of dollars. The creative thrill that the banker feels is at best a thrill at second hand. |

Read about J. C. Penney's and Thomas J. Watson Sr.'s "little civilizations."

|

Then, too, the public applauds the entrepreneur and industrialist more often than it praises the capitalist who makes their achievements possible. The capitalist may furnish the credit for creative effort, but they rarely get the credit for creative results.

The business of rightly administering our applause is a thing we Americans have never thought out.

But there are too many inviting by-paths to this discussion. I hope I have succeeded in what I set out to do, namely, to suggest that we business men might anticipate most of the discontent and forestall most of the revolutions of our time if we were our own severest critics and gave as much thought to the social implications of our business as we give to its purely financial aspects.

The capitalist point of view in business seemed to me one of the best illustrations of the sort of fundamental questions we business men must think through if we are to keep the modern business system secure against social assault. It seems to me one of the rusted links in the business armour.

If I have done nothing more than to call attention to it, I am satisfied.

The business of rightly administering our applause is a thing we Americans have never thought out.

But there are too many inviting by-paths to this discussion. I hope I have succeeded in what I set out to do, namely, to suggest that we business men might anticipate most of the discontent and forestall most of the revolutions of our time if we were our own severest critics and gave as much thought to the social implications of our business as we give to its purely financial aspects.

The capitalist point of view in business seemed to me one of the best illustrations of the sort of fundamental questions we business men must think through if we are to keep the modern business system secure against social assault. It seems to me one of the rusted links in the business armour.

If I have done nothing more than to call attention to it, I am satisfied.

Edward A. Filene, "The Way Out," 1924

This Author's Thoughts on Edward A. Filene's Article

|

The opening three insights of Mr. Filene into how demagogs can exploit unacknowledged societal problems seem as applicable today as it was in the 1920s, both economically and politically: (1) immoral content inbred in an economic or political system leads to (2) a justifiable moral discontent, which an ideological demagogue exploits to justify (3) an indefensible immoral discontent in society which, today, has taken the form (a) on the revolutionary extreme, of organized attacks on and destruction of private property and (b) on the reactionary extreme, the proposed overthrow of legitimately elected representatives of government.

I have to agree with Mr. Filene that “one of the social tragedies of our time lies in the fact that we rarely deal with moral discontent until it has reached its third stage—until it has entered the field as clearly formulated propaganda, when it has been captured by doctrinaires and demagogues.” I have to wonder if the “Silent Majority” of the late twentieth century through the inherent genetics of a social-media driven society has over-represented and over-amplified the views, voices, and negative vibrations of the revolutionary and the reactionary to produce a twenty-first century equivalent of not a new but an all too similar … “Self-Silenced Majority.”

|

This chapter is from Edward A. Filene’s “The Way Out.”

|

The technologies are new, the participants have changed, but human nature is the same: new parameters, new players, same problem.

- Interesting Insights into Tom Watson, Traditional Founder of IBM

One example of how Tom Watson avoided going down the “capitalist” or financial path during his tenure of leadership of the corporation was in how he trained his Chief Financial Officer (CFO).

|

He highlights this training in a presentation he gave at the opening session of the Controller’s Institute of America on September 19, 1932. The title of the presentation was “The Controller’s Responsibility.” This speech was given during the Great Depression.

He said, in part: “To me, the responsibilities of the controller come second only to those of the sales heads of the business. I believe that, if you can get a good sales organization, headed by a good sales manager, and then a good finance department, headed by a good controller, the problems of your business will be very simple to work out. … “It seems to me that the first duty of a controller is to forget his title, forget that the position he fills is merely to control the expenditures of cash. … The controller has to be an engineer, a purchasing agent, a credit man, a salesman, and a manufacturer as well as a financier. “[In order to accomplish this in our organization] … |

Select image to read the introduction and preface.

|

"I told our controller I would like him to spend his first year without taking up the duties of controller, that I would like him instead to spend the year visiting our factories, getting fully acquainted and thoroughly familiar with all that was going on in our factories and in our home office. Then we made it convenient for him to visit all our principal sales offices and to spend a great deal of time there getting acquainted with the sales end of the business. We also put him down to make a talk at every sales convention it was possible for him to attend. …

“I know that some people expect their controller to do only one thing, and that is prevent the expenditure of money. … I believe that the greatest service the controller can perform for the business is to find more ways to spend money where it will expand the business, and where it will bring in more orders to the factories.”

Tom Watson may have been The World’s Greatest Salesman, but he made sure that everyone, including the controller, was a salesman too. This speech fits quite nicely with the perspective that Edward A. Filene is making above, doesn't it?

Edward A. Filene and Thomas J. Watson Sr. were two great salesmen of their day.

“I know that some people expect their controller to do only one thing, and that is prevent the expenditure of money. … I believe that the greatest service the controller can perform for the business is to find more ways to spend money where it will expand the business, and where it will bring in more orders to the factories.”

Tom Watson may have been The World’s Greatest Salesman, but he made sure that everyone, including the controller, was a salesman too. This speech fits quite nicely with the perspective that Edward A. Filene is making above, doesn't it?

Edward A. Filene and Thomas J. Watson Sr. were two great salesmen of their day.

[Footnote #1] This author, in THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition, also uses the Shakespearean analogy with IBM’s transitionary, twenty-first-century chief executive, Louis V. Gerstner. Mr. Gerstner, though, is ultimately responsible for the corporation’s slide into the deepest of financial autocracies, and there is little doubt that were Edward A. Filene alive today, he would use the corporation as an additional example of the problems caused when long-term, build-something-to-last, industrialist-driven, chief executive thinking is replaced by a short-term, stock-manipulative, capitalist-driven, chief executive ideology of shareholder-first and -foremost.

[Footnote #2] This “good will” should not be confused with the twenty-first century concept of “goodwill,” both of which are intangible assets. The latter is an accounting means by which a corporation accounts for the excess purchase price of another company. Items included in twenty-first-century goodwill are such items as intellectual property and brand recognition. Neither good will nor goodwill are easily quantifiable assets, and both have been used at times as “water on the books” to inflate corporate assets beyond a reasonable and justifiable point.

[Footnote #2] This “good will” should not be confused with the twenty-first century concept of “goodwill,” both of which are intangible assets. The latter is an accounting means by which a corporation accounts for the excess purchase price of another company. Items included in twenty-first-century goodwill are such items as intellectual property and brand recognition. Neither good will nor goodwill are easily quantifiable assets, and both have been used at times as “water on the books” to inflate corporate assets beyond a reasonable and justifiable point.