If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

If my foresight were as clear as my hindsight, I should be better off by a damned sight.

IBM's Two-Decade-Long Employee Work Slowdown

|

|

Date Published: July 29, 2021

Date Modified: January 13, 2024 |

We have different ideas and different work, but when you come down to it there is just one thing we deal with throughout the whole organization—that is the "MAN."

Tom Watson Sr., Endicott, New York, 1915

IBM Is Experiencing a Non-Union, Two-Decade-Long, Work Slowdown

- The Danger that Lurks Beneath the Surface

- Productivity and IBM's 21st Century Human Relations' Policies

- Everything Depends on Productivity – Everything

- Co-location Did Not Reverse this Productivity Decline

- Understanding the Difference Between Macro-Level and Micro-Level Productivity

The Danger that Lurks Beneath the Surface

|

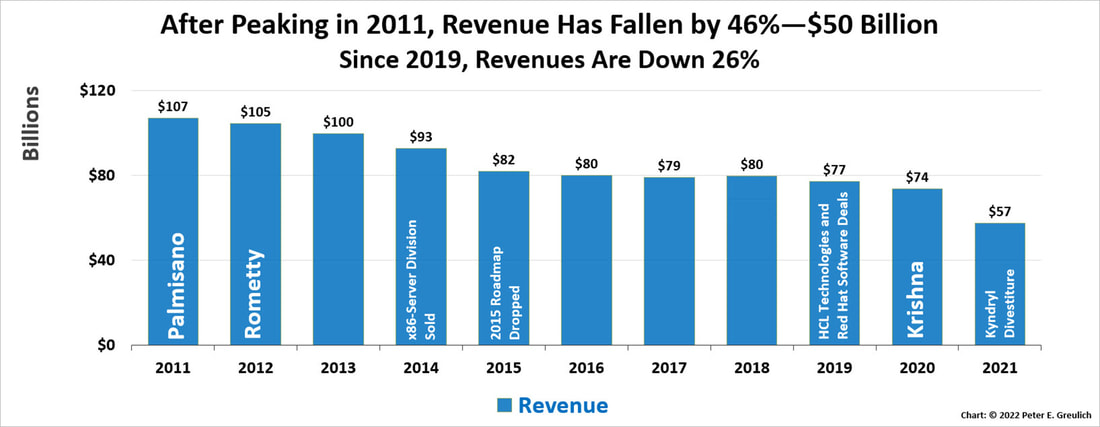

Most business analysts are writing about IBM’s weakening revenue. It is a very visible and dramatic decline: revenue that peaked at $107 billion in 2011 has fallen over the past ten years to $57 billion—an average drop in revenue of $5 billion every year. IBM’s chief executives have downplayed any concerns saying that revenue is just the sacrificial lamb necessary to achieve higher profitability.

|

IBM revenue is down $50 billion in the last decade.

|

From management’s perspective, IBM’s 46% decline in revenue over the last decade is the natural result of a strategy to offload a plethora of low-value products and services to build a lean-and-mean, profit-driven, product-delivering machine.

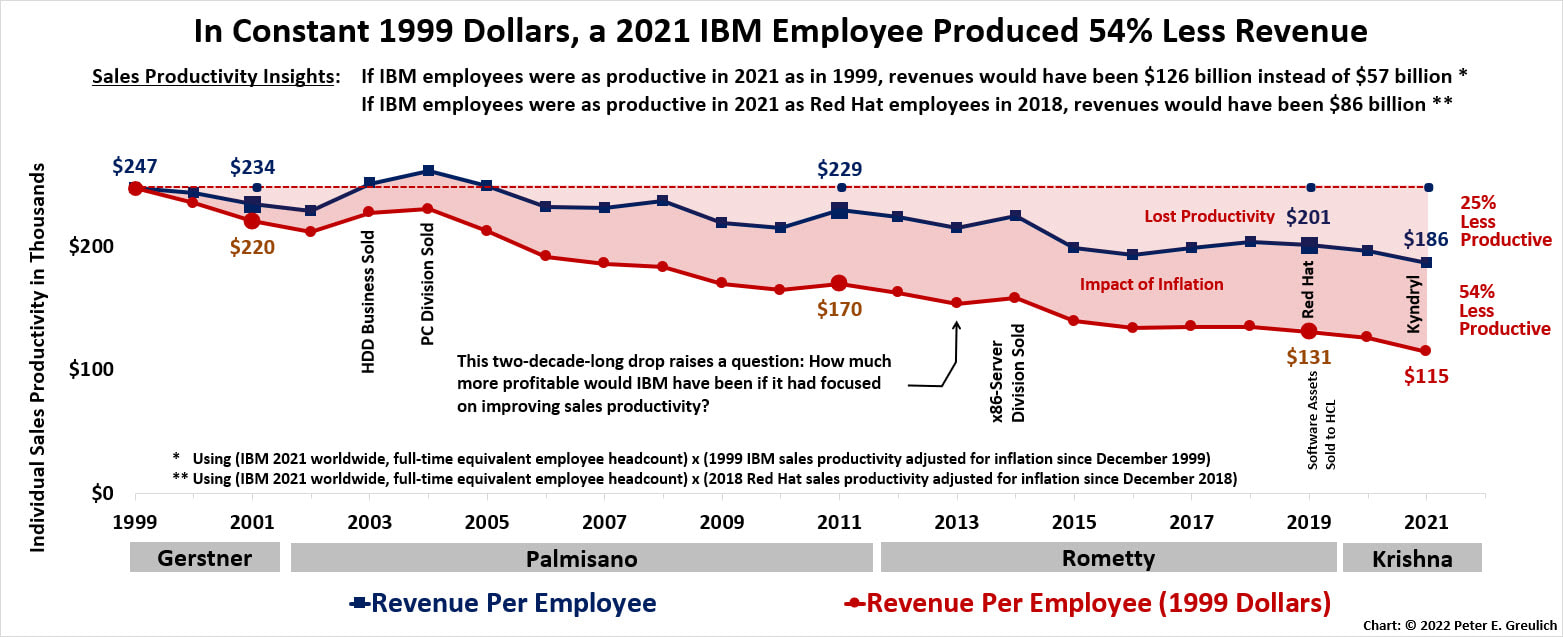

Unfortunately, what the corporation is experiencing is quite unnatural: in both constant 1999 dollars and current year-over-year dollars IBM’s sales productivity has fallen for two decades. Previously, the longest back-to-back drop in sales productivity was a string of four years caused by the Recession of 1920-21. Watson Sr., thirteen years later, said he was ashamed of his performance during this time and that he had just lost confidence in his company and his salesmen—he accepted responsibility. He fixed the problem. It was him, the individual sitting in the corner office.

Since the Great Depression’s trough in March 1933, IBM’s sales productivity had never dropped for more than a single year until the reign of Louis V. Gerstner—not even during the difficult financial crisis of the early ’90s. IBM’s declining revenue that has everyone’s attention is the very visible tip of a performance iceberg. The real threat to the company is not its last few years of declining revenue but its management’s inability to reverse their falling sales productivity over the last two decades.

If uncorrected, this is the unseen menace that could eventually sink one of the U.S.’s longest-lived corporations.

Since the Great Depression’s trough in March 1933, IBM’s sales productivity had never dropped for more than a single year until the reign of Louis V. Gerstner—not even during the difficult financial crisis of the early ’90s. IBM’s declining revenue that has everyone’s attention is the very visible tip of a performance iceberg. The real threat to the company is not its last few years of declining revenue but its management’s inability to reverse their falling sales productivity over the last two decades.

If uncorrected, this is the unseen menace that could eventually sink one of the U.S.’s longest-lived corporations.

- IBM's 21st Century Human Relations' Policies Have Driven Down Sales Productivity

Everything Depends on Employee Productivity – Everything

Henry Ford wrote that it was a business’ obligation to serve mankind. In his view, a corporation performs this service by first creating a product of value and then continually driving its quality up and its price down through improved manufacturing processes.

This expands sales in the existing market and speeds entry into new markets; thereby, the corporation maintains and improves its profitability, a portion of which is distributed in the form of higher wages to employees who, as wealthy consumers, can then afford the products they are producing [Read about Henry Ford's in-house fight with his shareholders over business-first.].

This expands sales in the existing market and speeds entry into new markets; thereby, the corporation maintains and improves its profitability, a portion of which is distributed in the form of higher wages to employees who, as wealthy consumers, can then afford the products they are producing [Read about Henry Ford's in-house fight with his shareholders over business-first.].

In Ford’s view, increasing productivity funds higher-value products for customers, improves benefits for employees, raises dividends for shareholders, and increases societal wealth. Today’s IBMer is producing almost 50% less revenue (in inflation adjusted dollars) than an IBMer from two decades ago. In 1999, every IBMer produced $247,000 in revenue. Since then—to just keep sales productivity in line with inflation—every employee should have increased their revenue production to $409,000 by the end of 2021. Instead, it dropped to $186,000 per employee. This is a shortfall of $223,000 per employee; which, when multiplied by IBM’s current employee population, is a very large dollar amount to vanish without a question from shareholders: $70 billion in lost sales.

|

One of the reasons IBM employees are not seeing performance raises and are experiencing an on-going deterioration in benefits is because they are less productive, but it is not their fault.

Management has spent its investment dollars elsewhere. Since 1995, IBM has invested $201 billion in its own stock and, since 2001, $92 billion on 207 acquisitions—a total of more than a quarter of a trillion dollars. Meanwhile, it has spent little of matching significance on its people, processes, and products. |

Capitalism needs more industrialist-minded CEOs

|

IBM’s employees are examples of the cobbler’s children who have no shoes.

Co-location Did Not Reverse this Productivity Decline

In 2017, IBM’s solution for its productivity problem was called co-location: moving its employees to centers of work. The irony of this strategic change wasn't lost on IBM’s employees. Under the guise of improving productivity, IBM pursued a two-decade-long strategy called workload rebalancing that moved workloads to people (generally, lower-wage and overseas). Now it was moving its people to the workloads? As the chart (above) documents, workload rebalancing (2005 through 2011) was a sales productivity disaster, and co-location did little other than to slow the overall downward trend for a few years.

The problem at IBM has never been so much who is doing the work and where; but (1) the motivation of the person doing the work, (2) the proper tools to get the job done, and (3) the competence of the person in charge. IBM’s leadership has forgotten that it is the passion, enthusiasm and engagement of the individual—the “MAN”—who will produce the largest positive impact on a corporate bottom line.

The problem at IBM has never been so much who is doing the work and where; but (1) the motivation of the person doing the work, (2) the proper tools to get the job done, and (3) the competence of the person in charge. IBM’s leadership has forgotten that it is the passion, enthusiasm and engagement of the individual—the “MAN”—who will produce the largest positive impact on a corporate bottom line.

Understanding the Difference Between Macro-Level and Micro-Level Productivity

|

Unfortunately, too many of IBM's executives are the type to try and weather any economic or political storm by manufacturing a blizzard of their own: marketing statements that always flow, uncontroversially, with conventional wisdom and opinions. Rarely are their messages ... educational, challenging, informative.

What is needed is strong talk from a leadership that positions both the needs of the individual with the needs of the business. If a business fails to produce profits, the individual will find themselves on the street. |

Read about IBM's first attempt at "Work at Home"

|

This requires a healthy, robust communication between employer and employee.

The technology industry as a whole (and IBM as an example within its industry) needs a tough discussion of micro-level (individual) productivity versus macro-level (business) productivity. Although a business can, should and must be sensitive to the needs of the individual, it also has to have big-boy-and-girl talks with its employees. It needs to level set its employees that the ability to provide ever-improving, individual benefits is dependent on macro-level or corporate productivity as measured in the chart above.

While employees may feel or even be more "individually" productive, the true test for a business is if they are being productive as a team. Is the team winning? In the case of corporations this means selling more at a profit.

Let's put this discussion in a form that most people can understand, a sports analogy. At the end of a game, as Vince Lombardi used to say, it doesn't matter what kind of statistics a quarterback racks up during a contest if the team finds itself on the losing end of what is posted on the scoreboard. A self-centered quarterback will discuss his performance—how good he feels. A truly concerned quarterback will ask his team what he—or we—could be doing differently, because what "we" are doing didn't have the desired outcome: winning.

There is a big difference between individual and team productivity. It is absolutely the obligation of the corporate executive to monitor, adjust and adapt to ensure that corporate productivity keeps improving. It is from this macro-level productivity that benefits can be—and should be—distributed to employees, shareholders, customers and society.

Only if a corporation is successful at being productive as a team (macro-level) will the individual see benefits continue to flow, and IBM can't lead this discussion until it acknowledges that its current practices and strategies have been driving sales productivity lower over the last two decades.

Those discussions, it appears, will require a change of leadership because . . .

Arvind has started them, has he?

Cheers,

- Peter E.

The technology industry as a whole (and IBM as an example within its industry) needs a tough discussion of micro-level (individual) productivity versus macro-level (business) productivity. Although a business can, should and must be sensitive to the needs of the individual, it also has to have big-boy-and-girl talks with its employees. It needs to level set its employees that the ability to provide ever-improving, individual benefits is dependent on macro-level or corporate productivity as measured in the chart above.

While employees may feel or even be more "individually" productive, the true test for a business is if they are being productive as a team. Is the team winning? In the case of corporations this means selling more at a profit.

Let's put this discussion in a form that most people can understand, a sports analogy. At the end of a game, as Vince Lombardi used to say, it doesn't matter what kind of statistics a quarterback racks up during a contest if the team finds itself on the losing end of what is posted on the scoreboard. A self-centered quarterback will discuss his performance—how good he feels. A truly concerned quarterback will ask his team what he—or we—could be doing differently, because what "we" are doing didn't have the desired outcome: winning.

There is a big difference between individual and team productivity. It is absolutely the obligation of the corporate executive to monitor, adjust and adapt to ensure that corporate productivity keeps improving. It is from this macro-level productivity that benefits can be—and should be—distributed to employees, shareholders, customers and society.

Only if a corporation is successful at being productive as a team (macro-level) will the individual see benefits continue to flow, and IBM can't lead this discussion until it acknowledges that its current practices and strategies have been driving sales productivity lower over the last two decades.

Those discussions, it appears, will require a change of leadership because . . .

Arvind has started them, has he?

Cheers,

- Peter E.