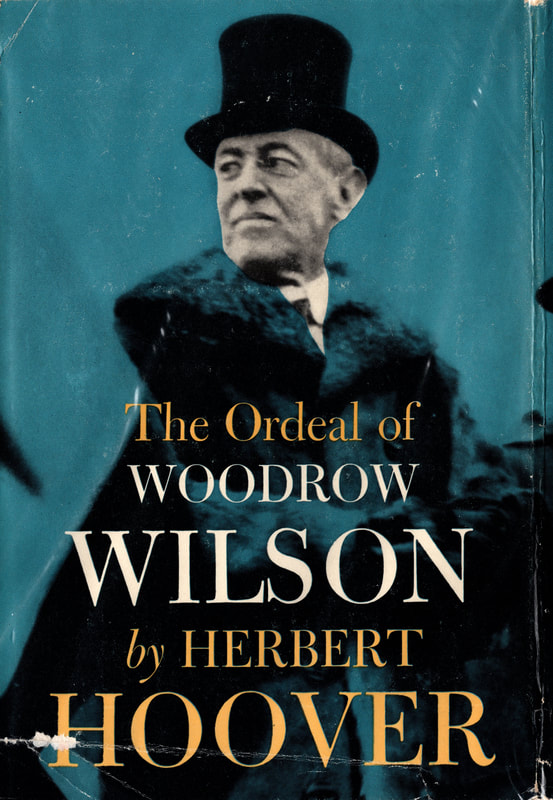

A Review of "The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson"

|

|

Date Published: July 1, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

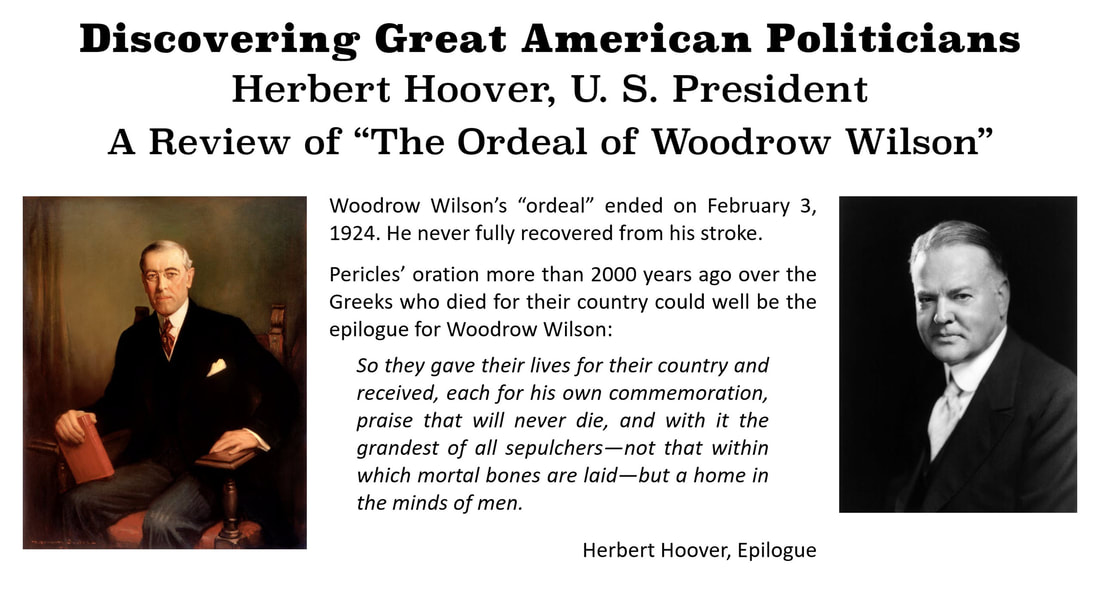

This is an unusual book that is written by one former president evaluating another former president ... from different parties! When Herbert Hoover (Republican) writes with admiration about Wilson (Democrat), it should be considered high praise. An amazing work that also documents what Hoover accomplished in saving Belgian and European lives during and after World War I—with the support of President Wilson, the subject of his book.

Hoover doesn't boast, but only writes the facts to establish his credibility as a reliable, credible source of information on what is presented in this book about one of our former U.S. Presidents.

Hoover doesn't boast, but only writes the facts to establish his credibility as a reliable, credible source of information on what is presented in this book about one of our former U.S. Presidents.

Peter E. Greulich, Review of "The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson", August 21, 2020

A Review of "The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson" by Herbert Hoover

- The Preface: Hoover on Woodrow Wilson

- Reviews of the Day: 1943

- The Choice at Versailles: An Old World or a New World Vision

- Understanding Herbert Hoover through His Work with Woodrow Wilson

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

The Preface: Hoover on Woodrow Wilson

“My association with him was such that I formed convictions as to his philosophy of life, his character and his abilities which have deepened during these four decades. My appraisal of him is based solely on my own experiences with him and my knowledge of the forces with which he had to deal. …

“He possessed great clarity of thought, with an ability quickly to reduce problems to their bare bones. His public addresses were often clothed with great eloquence. As a Jeffersonian Democrat, he was a ‘liberal’ of the nineteenth century cast. His training in history and economics rejected every scintilla of socialism, which today connotes a liberal.

“His philosophy of American living was based upon free enterprise, both in social and in economic systems. He held that the economic system must be regulated to prevent monopoly and unfair practices. He believed that federal intervention in the economic or social life of our people was justified only when the task was greater than the states or individuals could perform for themselves.

“He yielded with great reluctance to the partial and temporary abandonment of our principles of life during the war, because of the multitude of tasks with which the citizen or the states could not cope.”

“He possessed great clarity of thought, with an ability quickly to reduce problems to their bare bones. His public addresses were often clothed with great eloquence. As a Jeffersonian Democrat, he was a ‘liberal’ of the nineteenth century cast. His training in history and economics rejected every scintilla of socialism, which today connotes a liberal.

“His philosophy of American living was based upon free enterprise, both in social and in economic systems. He held that the economic system must be regulated to prevent monopoly and unfair practices. He believed that federal intervention in the economic or social life of our people was justified only when the task was greater than the states or individuals could perform for themselves.

“He yielded with great reluctance to the partial and temporary abandonment of our principles of life during the war, because of the multitude of tasks with which the citizen or the states could not cope.”

Herbert Hoover, Preface to The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson

Reviews of the Day: 1943

|

“Herbert Hoover’s latest book … is unique in that it is the first time a former president has written a book about a predecessor in the White House. The book may impress some readers as being more about Mr. Hoover than about Mr. Wilson, but the author had to cite his own work to demonstrate the great administrative ability, power to make prompt decisions, cooperativeness, and humanitarianism [of Woodrow Wilson].”

The Staunton Leader, Editorial, April 29, 1958

“Published this week, is a work of major importance for our time. In reflective mood, far removed from the plane of partisanship, the Republican former President who was an aide of the Democratic leader of World War I offers a significant new appraisal of Wilson’s losing battle for a just peace and the League of Nations.”

Van Allen Bradley, The Passaic Herald-News, May 2, 1958

|

The Choice at Versailles: An Old World or a New World Vision

It is fascinating to read a history of how Europeans and Americans viewed the world so differently in the first quarter of the 20th Century. The following “New World Vision” as presented by Herbert Hoover is consistent with that presented by Mark Sullivan in Our Times: 1900–1925—an excellent work that Mr. Sullivan wrote to capture the changes in American culture during this time period.

|

“The American people had been implacably anti-imperial, anticolonial, and generally anti-the-subjugation-of-one-people-by-another from the day of our Declaration of Independence.

“Through the Monroe Doctrine, we had stopped the expansion of European empires in the Western Hemisphere. By the Spanish-American War, we had freed Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines from the Spanish Empire.

“We had established the independence of Cuba and were now building self-government in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.” |

It was "Old World" vs. "New World" at Versailles

|

Mr. Hoover then describes why Woodrow Wilson’s “New World Vision,” after the people of Europe hailed him as a hero, was viewed with so much suspicion by their leadership.

“With his flaming banner of the ‘Fourteen Points and the subsequent addresses,’ his eloquence about self-determination, his denunciations of annexations and ‘bandying peoples about,’ Mr. Wilson was a menacing intruder in the concepts of British, French and Italian statesmen and a threat to their secret treaties dividing all Europe."

Hoover then drives the point home.

“All the warring nations of Europe were economically exhausted, desperate, and most of them were hungry. Those twenty-seven nations were less interested in preserving peace for some distant future than in immediately righting their wrongs and ensuring their economic recovery.

“With his flaming banner of the ‘Fourteen Points and the subsequent addresses,’ his eloquence about self-determination, his denunciations of annexations and ‘bandying peoples about,’ Mr. Wilson was a menacing intruder in the concepts of British, French and Italian statesmen and a threat to their secret treaties dividing all Europe."

Hoover then drives the point home.

“All the warring nations of Europe were economically exhausted, desperate, and most of them were hungry. Those twenty-seven nations were less interested in preserving peace for some distant future than in immediately righting their wrongs and ensuring their economic recovery.

|

Attribution: Photos of the Great War

|

“Their representatives in Paris well knew that they would have to go home to their people, still torn by these emotions, to seek approval of the agreements at the Peace Conference. They had to bring back to their people annexations and reparations.

“Their continuation in power depended upon that.” |

To understand the callousness of the Old World Order, read the chapter “Woodrow Wilson’s Ordeal of the Food Blockade of Europe.” Here is a short excerpt showing the disgust of the British soldiers who occupied Germany for the enforcement of the food blockade by the French, Italian and their own British governments.

General Plumer, Commander of the British Occupation Army in Germany, told the Allied leadership that:

“The rank and file of his army were sick and discontented and wanted to go home because they could not stand the sight of hordes of skinny and bloated children pawing over the offal from British cantonments. His soldiers were depriving themselves to feed these kids.”

Woodrow Wilson and Americans were the only ones who believed in healing the war wounds quickly, but as Hoover would write later ... we had not had the Germans try twice to destroy our country. …

General Plumer, Commander of the British Occupation Army in Germany, told the Allied leadership that:

“The rank and file of his army were sick and discontented and wanted to go home because they could not stand the sight of hordes of skinny and bloated children pawing over the offal from British cantonments. His soldiers were depriving themselves to feed these kids.”

Woodrow Wilson and Americans were the only ones who believed in healing the war wounds quickly, but as Hoover would write later ... we had not had the Germans try twice to destroy our country. …

… Maybe it was (still is) impossible for us to completely understand.

Understanding Herbert Hoover through His Work with Woodrow Wilson

|

As much as I enjoyed reading about Woodrow Wilson, this book added a depth of character and an understanding of the humanity of Herbert Hoover, much of which it seems has been lost in history. When Hoover wrote of what he accomplished to keep a devastated continent fed and clothed after years of war, a great respect grew for the man.

The book reveals his stand to recognize Finland after the war and it was easily understood why he rushed to Finland’s aid at the beginning of World War II in establishing the Finnish Relief Fund (Thomas J. Watson Sr. was one of the first large contributors to the fund and a member of its founding board in December 1939.) Hoover was more than what I believed him to be before reading this book: a president mostly defined by being in office at the start of the Great Depression. For example, he writes of his efforts during World War I to relieve the suffering of the victims of war—a responsibility assigned to him by President Woodrow Wilson [this is from multiple excerpts across the book]. |

“I directed the relief of 10,000,000 people in Belgium and Northern France who were victims of occupation by the German Army and were blockaded by the Allies. … At that time, the people in Belgium and Northern France, normally dependent on imports for 70 per cent of their food, were being crushed between the millstones of the Allied blockade of Germany and the German armies which had invaded them. …

“I had to obtain agreements with the Germans for protection of supplies, and with the British and French for permission to pass through their blockade. In these negotiations I had the patronage of the American, Spanish and Dutch Ambassadors or their Ministers in London, Paris, Berlin, and Brussels. …

“I was probably the only American civilian allowed to pass freely between these cities. The administration of this huge enterprise required frequent contact with the British, French and German Prime Ministers, their Cabinet members and their military authorities. … I had need for support from President Wilson and members of his Cabinet.”

Yet, he wasn’t immune to what he saw in his efforts to feed the helpless caught in the middle.

“I was an eyewitness to the savagery of the German Army in their invasion of Belgium. I had, for two years, to pass by the wantonly destroyed university and cathedral of Louvain and the gaunt skeletons of destroyed villages.

“Even in my dreams forty years after, I was haunted by the monument at Dinant, which pathetically records the names of over two hundred men, women and children who had been seized as hostages and mowed down with machine guns because someone had fired a shot from a roof.

“I was an eyewitness to the brutal deportation of workmen to German work camps. And my only purpose for enduring these sights was to take part in saving 10,000,000 human beings from starvation because of the Germans.”

After the war he had to put those feelings aside as he was asked to take on the responsibility of coordinating the feeding of the entire continent of Europe—including Germany—which had to survive starvation and pestilence until the first crops could be harvested.

“During the peacemaking, and for some time after, I administered the Relief and Reconstruction of Europe directly under the President, but on behalf of all the victorious governments. That work required an organization in more than thirty countries with constant dealings with the Prime Ministers and high officials of each of the governments in Europe. Our organization included about 4,000 able Americans and many more thousands of local assistants. …"

In one amazing chapter he describes the ordeal of administering this relief, he writes:

“We had long since been in battle with three of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – Death, Destruction and Famine. Then came the Fourth – Pestilence. … Typhus was sweeping westward from all along the line of the old Russian western front. … Typhus is transmitted by lice. Its spread was stimulated by the scarcity of soap, since people ate the fats ordinarily used to make soap. And pestilence was intensified by debilitation from the lack of food, the destruction of homes and the filthy conditions in overcrowded hovels. …

"The American Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies at Geneva stated that they had neither staff nor resources to deal with it. …"

Unfortunately, neither did Herbert Hoover, so he appealed to General Pershing. The General’s and the U.S. Army’s response he documents superbly.

“The General cooperated fully, and we ultimately obtained about 1,400 Army personnel of all ranks, including hundreds of efficient sergeants. I obtained the delousing equipment of the American Army. Also in their first installment were 1,500,000 suits of underclothes, 3,000 beds, 10,000 hair clippers, 250 tons of soap, and 500 portable baths …

“We formed a line of battle in front of the typhus areas hundreds of miles long - a ‘sanitary cordon.’ With the aid of local police, traffic was stopped across this line except to persons with ‘deloused’ certificates or with assured recovery beyond the infection stage. Then Colonel Gilchrist’s staff, with the aid of the police and health authorities, gradually deloused, disinfected and re-clothed the people, village by village, in a general movement eastward."

What an amazing story of humanity … and maybe after Covid, we can comprehend better what it took, and …

“I had to obtain agreements with the Germans for protection of supplies, and with the British and French for permission to pass through their blockade. In these negotiations I had the patronage of the American, Spanish and Dutch Ambassadors or their Ministers in London, Paris, Berlin, and Brussels. …

“I was probably the only American civilian allowed to pass freely between these cities. The administration of this huge enterprise required frequent contact with the British, French and German Prime Ministers, their Cabinet members and their military authorities. … I had need for support from President Wilson and members of his Cabinet.”

Yet, he wasn’t immune to what he saw in his efforts to feed the helpless caught in the middle.

“I was an eyewitness to the savagery of the German Army in their invasion of Belgium. I had, for two years, to pass by the wantonly destroyed university and cathedral of Louvain and the gaunt skeletons of destroyed villages.

“Even in my dreams forty years after, I was haunted by the monument at Dinant, which pathetically records the names of over two hundred men, women and children who had been seized as hostages and mowed down with machine guns because someone had fired a shot from a roof.

“I was an eyewitness to the brutal deportation of workmen to German work camps. And my only purpose for enduring these sights was to take part in saving 10,000,000 human beings from starvation because of the Germans.”

After the war he had to put those feelings aside as he was asked to take on the responsibility of coordinating the feeding of the entire continent of Europe—including Germany—which had to survive starvation and pestilence until the first crops could be harvested.

“During the peacemaking, and for some time after, I administered the Relief and Reconstruction of Europe directly under the President, but on behalf of all the victorious governments. That work required an organization in more than thirty countries with constant dealings with the Prime Ministers and high officials of each of the governments in Europe. Our organization included about 4,000 able Americans and many more thousands of local assistants. …"

In one amazing chapter he describes the ordeal of administering this relief, he writes:

“We had long since been in battle with three of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – Death, Destruction and Famine. Then came the Fourth – Pestilence. … Typhus was sweeping westward from all along the line of the old Russian western front. … Typhus is transmitted by lice. Its spread was stimulated by the scarcity of soap, since people ate the fats ordinarily used to make soap. And pestilence was intensified by debilitation from the lack of food, the destruction of homes and the filthy conditions in overcrowded hovels. …

"The American Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies at Geneva stated that they had neither staff nor resources to deal with it. …"

Unfortunately, neither did Herbert Hoover, so he appealed to General Pershing. The General’s and the U.S. Army’s response he documents superbly.

“The General cooperated fully, and we ultimately obtained about 1,400 Army personnel of all ranks, including hundreds of efficient sergeants. I obtained the delousing equipment of the American Army. Also in their first installment were 1,500,000 suits of underclothes, 3,000 beds, 10,000 hair clippers, 250 tons of soap, and 500 portable baths …

“We formed a line of battle in front of the typhus areas hundreds of miles long - a ‘sanitary cordon.’ With the aid of local police, traffic was stopped across this line except to persons with ‘deloused’ certificates or with assured recovery beyond the infection stage. Then Colonel Gilchrist’s staff, with the aid of the police and health authorities, gradually deloused, disinfected and re-clothed the people, village by village, in a general movement eastward."

What an amazing story of humanity … and maybe after Covid, we can comprehend better what it took, and …

… America’s part in saving so many people on the continent of Europe.

This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

|

I grew to respect two men in reading this book: Woodrow Wilson and Herbert Hoover. How does one explain the supposed failure of Woodrow Wilson? First, it was a failure of aiming too high. He spoke and dreamed of a world without war. One has to question, if it is better to have a leader who believes war is the natural human condition and never works for peace—only prepares his countrymen to win the next war; or to have a leader who believes peace is possible and acts as if man can attain peace and sets that expectation.

Personally, I would find it a terrible day if all human beings accepted war as our eternal human condition. Woodrow Wilson was initially greeted by the multitude of ethnic races across Europe because he personified the possible attainment of peace and freedom they so desired. Disillusionment came when, as much as he tried, he couldn’t deliver that peace. |

Why couldn’t he build a worldwide peace? I believe Herbert Hoover often repeats the reason in this book: There was an "Old World Order" that Woodrow Wilson never fully understood. If he had, he would have gotten down in the muck to fight for his "New World Order."

These few paragraphs, to me, are the essence of Woodrow Wilson’s Ordeal:

“A leader more versed in the European school of diplomacy might have dictated the peace. He [Woodrow Wilson] could have demanded his share of territorial spoils and enemy reparations and could have traded them for concessions to his views. He could have stopped the huge American loans upon which many of these nations depended for their continued existence. He even could have threatened to cut off the daily bread which America alone could supply.

“The use of such power would not have been in accord with American ideals. The President’s disavowal of its application, in advance, no doubt weakened him in his negotiations. He was too great a man to bargain in that way [emphasis added].

“American idealism indeed was unfitted to participate in a game played with power as the counters.”

Yes, Americans want their leaders to be virginally spotless when they speak of themselves, their policies, or their beliefs, but in order to deliver on those policies, our unwillingness to accept even a temporary setback sometimes demands a devil behind closed doors. Isn’t this the heart of many a movie script: the story of a good man or woman who must sometimes live and act in compromisingly grey areas, to deliver on their promise?

Can the hero/heroine then extricate their souls unblemished from what they had to do to accomplish those ends?

Subliminally, Herbert Hoover’s book consistently poses one question, “Do the ends justify the means?” …

These few paragraphs, to me, are the essence of Woodrow Wilson’s Ordeal:

“A leader more versed in the European school of diplomacy might have dictated the peace. He [Woodrow Wilson] could have demanded his share of territorial spoils and enemy reparations and could have traded them for concessions to his views. He could have stopped the huge American loans upon which many of these nations depended for their continued existence. He even could have threatened to cut off the daily bread which America alone could supply.

“The use of such power would not have been in accord with American ideals. The President’s disavowal of its application, in advance, no doubt weakened him in his negotiations. He was too great a man to bargain in that way [emphasis added].

“American idealism indeed was unfitted to participate in a game played with power as the counters.”

Yes, Americans want their leaders to be virginally spotless when they speak of themselves, their policies, or their beliefs, but in order to deliver on those policies, our unwillingness to accept even a temporary setback sometimes demands a devil behind closed doors. Isn’t this the heart of many a movie script: the story of a good man or woman who must sometimes live and act in compromisingly grey areas, to deliver on their promise?

Can the hero/heroine then extricate their souls unblemished from what they had to do to accomplish those ends?

Subliminally, Herbert Hoover’s book consistently poses one question, “Do the ends justify the means?” …

… to his death bed, Woodrow Wilson believed not.

An absolutely great book. Highly recommended!

Cheers,

- Pete

Cheers,

- Pete