Lou Gerstner wrote, "People truly do what you inspect, not what you expect." … Lest we forget, these "inspection pages" exist because chief executives are "people" too.

Arvind Krishna: First One Hundred Days Performance

|

|

Date Published: July 22, 2021

|

In a radio broadcast on July 24, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), looking back on his activities after taking office, reviewed his initial one hundred days—a short period of time he devoted to “starting the machinery of the ‘New Deal.’” From this broadcast, the press coined the phrase “The First 100 Days.”

Traditionally, this is a period of time for a chief executive to not only discover, understand, and acknowledge the issues facing their country or corporation, but to start resolving them. During this time, FDR called the government and its businesses to action. His rallying cry told the citizens of his country that its government was on the job. Ever since then, the first one hundred days of any chief executive officer’s term has become a significant checkpoint on the performance of a new corner office. It is an early, traditional, and very relevant checkpoint of a chief executive’s performance. It is a time to ask, “Is the chief executive setting the proper tone and taking the appropriate actions to ensure their corporation’s future success? Has he or she told the citizens of their corporation through words and actions that their chief executive is on the job?

Wednesday, July 15, 2020 marks the end of "The First 100 Days" for Arvind Krishna, IBM’s chief executive officer.

What does this one-hundred-day checkpoint reveal?

Is there an IBM “New Deal?”

Or the same old stuff?

Traditionally, this is a period of time for a chief executive to not only discover, understand, and acknowledge the issues facing their country or corporation, but to start resolving them. During this time, FDR called the government and its businesses to action. His rallying cry told the citizens of his country that its government was on the job. Ever since then, the first one hundred days of any chief executive officer’s term has become a significant checkpoint on the performance of a new corner office. It is an early, traditional, and very relevant checkpoint of a chief executive’s performance. It is a time to ask, “Is the chief executive setting the proper tone and taking the appropriate actions to ensure their corporation’s future success? Has he or she told the citizens of their corporation through words and actions that their chief executive is on the job?

Wednesday, July 15, 2020 marks the end of "The First 100 Days" for Arvind Krishna, IBM’s chief executive officer.

What does this one-hundred-day checkpoint reveal?

Is there an IBM “New Deal?”

Or the same old stuff?

The First 100 Days: The Performance of IBM’s Chief Executive

- IBM’s Cultural Crisis of 1999–2019

- The First Leadership Test: Reporting Big Blue-and-Red Revenue Results

- Human "Assets" Are Now Leaving of Their Own Accord

- The Executive Pulpit Should be Educational, Introspective, and Expansive

- The Author’s Opinion: “The First Hundred Days” Was a Missed Opportunity

Chief Executives need to project words and actions to simultaneously make our country’s citizens grateful for what they have, but also constantly uncomfortable with how much more we have yet to accomplish. This balance between grateful and uncomfortable requires men and women who are introspective, well-spoken, and of great character.

Peter E. Greulich, Author, Public Speaker, and Self-Publisher

IBM’s Cultural Crisis of 1999–2019

|

On April 6, 2020, Arvind Krishna inherited the chief executive officer’s desk in the corner office of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). To compare the urgency for action at IBM with that of the United States of America during the Great Depression under the presidency of FDR is rather dramatic, but it is less only in scale. The need for quick, corrective, and decisive action is indistinguishable. In Arvind’s case, he must stop the further decay of one of the world’s greatest corporations.

Consider the following record inherited by Krishna from Virginia M. Rometty: In those areas where the law requires transparency, Virginia M. Rometty’s record was as follows: year-over-year revenue growth was consistently negative and profit growth was, at best, erratic; sales productivity was down 12% and profit productivity was down 28%; revenues were down 28% and profit was down 41%; and the company lost almost half of its market value—44%. |

Employee engagement and customer satisfaction, two areas where ethics demands transparency but the law does not, were, at a minimum, unmentionably low and most likely uncompetitive. Even as executives spent more money on share repurchases, employees waved off the opportunity to purchase their corporation’s shares at a discount. Warren Buffett invested, took a look around, and left.

Shareholders who stuck around lost money and saw risk rise astronomically. Strong, high-performing employees lost employment, and profitable, loyal customers lost a trusted vendor. Supportive societies that had sheltered the company for more than eight decades suffered from economic disinvestment as the company invested in paper instead of in people, processes, and products.

THINK Again! IBM: The Rometty Edition

In most areas, these trends were the continuation of the corporation’s relentless, twenty-first-century decline, but one record stands out from all the rest: the corporation’s 50% drop in market value. If the United States of America’s gross national product (GDP) had dropped a similar amount over the last two decades, the coming decade would be a time of crisis. The country’s citizens would be demanding action from its leadership.

Some observe that IBM has faced and surmounted many similar crises in its past, and this is partially true. Unfortunately, IBM is facing a crisis unlike the five found in its past: (1) the Crisis of 1914–15, (2) the Crisis of 1920–21, (3) the Crisis of 1933–34, (4) the Crisis of 1964–65, and (5) the Crisis of 1992–93. All of these except one were financial crises. The one exception is the Crisis of 1914–1915 which was both a financial and a cultural crisis. This is when Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM, took charge of the C‑T‑R Company.

In 1930, he offered this hindsight observation of the company’s culture in 1915:

Some observe that IBM has faced and surmounted many similar crises in its past, and this is partially true. Unfortunately, IBM is facing a crisis unlike the five found in its past: (1) the Crisis of 1914–15, (2) the Crisis of 1920–21, (3) the Crisis of 1933–34, (4) the Crisis of 1964–65, and (5) the Crisis of 1992–93. All of these except one were financial crises. The one exception is the Crisis of 1914–1915 which was both a financial and a cultural crisis. This is when Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM, took charge of the C‑T‑R Company.

In 1930, he offered this hindsight observation of the company’s culture in 1915:

We had very little enthusiasm, but what we did have … gave us a great start, and the other men fell in line. Enthusiasm is the basis of all great things.

Thomas J. Watson Sr., 1930

Today, the corporation is once again in the midst of a cultural crisis. Gallup measures employee engagement. Deloitte writes about employee passion. Tom Watson Sr. looked in the eyes of his employees for enthusiasm. However you measure employee morale, IBM is in a crisis. Its first cultural crisis in over one hundred years. Those who constantly parrot that the corporation has faced similar crises like those above and surmounted them, do not understand IBM’s history, the strength of its twentieth-century culture, and the power of its one-time, self-sustaining stakeholder ecosystem – or the depths of its twenty-first-century, systemic, cultural problems.

This crisis is different: It is the Cultural Crisis of 1999–2019.

This is a crisis—two decades in the making.

Arvind’s first 100 days mattered to IBMers . . .

. . . just as much as FDR’s did to Americans.

This crisis is different: It is the Cultural Crisis of 1999–2019.

This is a crisis—two decades in the making.

Arvind’s first 100 days mattered to IBMers . . .

. . . just as much as FDR’s did to Americans.

The First Leadership Test: Reporting Big Blue-and-Red Revenue Results

On April 20, 2020, Arvind showed up for his initial analysts’ call to review first-quarter results. This was a pleasant break from the Rometty tradition of “never” showing up, and it was an encouraging sign. Unfortunately, his CFO continued his obfuscation of the corporation’s revenue problems. In the meeting, the CFO reported a quarter-to-quarter revenue shortfall of 3.4% ($18.182 billion to $17.571 billion) and adamantly noted that “adjusting for divested businesses and currency,” revenue was “actually up .1%.” Questionably, the CFO did not adjust for the corporation’s only acquired business in 2019—what the corporation’s annual report called the “largest business acquisition” in its history.

|

Adjusted for the Red Hat acquisition, the first-quarter 2019 revenue number would have been approximately $19.061 billion. This number includes IBM revenue of $18.182 billion plus Red Hat’s revenue from December 2018 to February 2019 of $879 million (see sidebar). Revenue was down 7.82%, not 3.4%. So, revenue was down significantly again—even adjusted for divestitures and currency. Obscuring such critical revenue details, raises doubts when the CEO speaks on other critical topics, such as “IBM’s Principles of Trust and Transparency.” To believe such principles, all executives must be trustworthy and transparent. In all matters, they must speak with clarity and complete honesty.

It is the chief executive’s responsibility to enforce this honesty and integrity at all levels of their organization. Arvind Krishna’s and his executives’ words need supportive actions. Unfortunately, there has been significant conflict between the executives’ words and actions for decades and across all realms—economic, political and social. Such practices are causing internal morale problems and external credibility issues that the chief executive needed to address. |

Unfortunately, a few short weeks after taking over his new position, Arvind Krishna failed to ensure a high level of financial transparency during this revenue announcement. The following day, the corporation moved to squelch transparency even further in Austin, Texas. A month later the corporation told all its employees that this first quarter under their new chief executive would be business as usual. It confirmed a new resource action and, in confirming it, failed the “why, “who,” “where,” and “how many” transparency tests.

Human "Assets" Are Now Leaving of Their Own Accord

On April 21, 2020, the corporation settled a major lawsuit to prevent an embarrassing discovery process that would have revealed just how biased the corporation has been in its workload rebalancing—a former IBM Vice President of Human Resources suggested that the company had fired [through techniques such as resource actions and workload rebalancing] as many as 100,000 employees “over the past several years” in order to make its workforce younger. Then on May 22, 2020, the corporation confirmed that Arvind Krishna was not slowing down or stopping this abhorrent human resource practice—with its underlying age-discrimination bias.

|

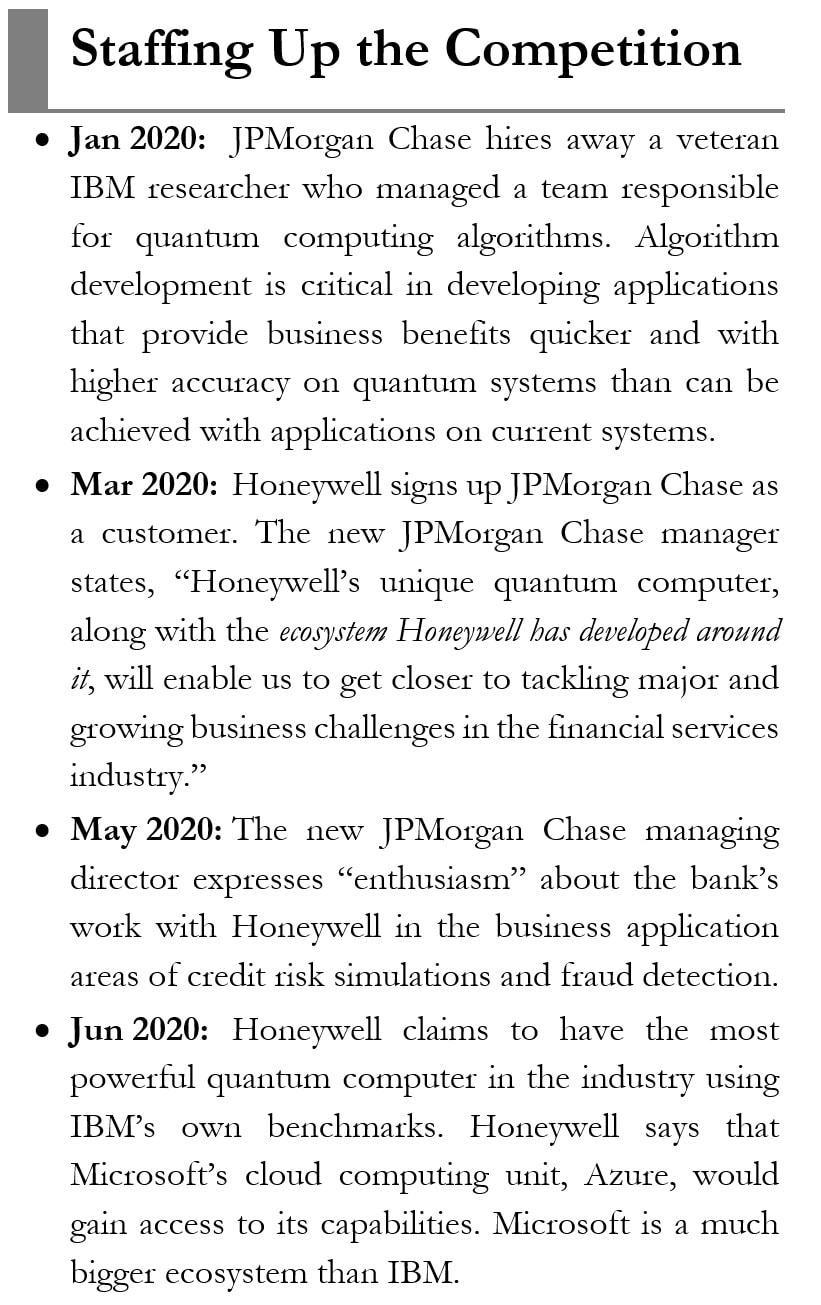

Stopping these resource actions could have slowed, halted or even reversed IBM’s two-decade-long drop in sales and profit productivity. Employees find it hard to remain productive when every job within the corporation is at risk—not just the “old guy’s” job. But massive resource actions protect the corporation’s relentless, short-term efforts to artificially boost earnings-per-share. This practice has created a work environment that is so toxic that even the best-of-the-best hold their noses as they head off to work (or in today’s environment, power up their computer to start working from home). Many are leaving of their own accord, and IBM continues to see their effect in the determined eyes of their former employees turned competitor. IBM is staffing up its competition with highly motivated, top-notch skills (see sidebar).

The corporation implemented these resource actions while the corner office was most likely composing an article for release on June 1, 2020, entitled “Standing Together.” Reading the comments shows the internal and external conflicts within the organization. This resource action undermined the chief executive’s words as his company again refused to be transparent concerning the specifics of the resource action. While Arvind Krishna has been articulate on the race issue in the United States, the corporation is still stoking the fires of an inter-generational conflict in how it has been cutting “Old Heads” for decades. |

Implementing an end to resource actions and age-discrimination practices would have gone a long way to building a trusting workplace where employees believe the words of the corner office rather than constantly questioning its motives and fearing its actions.

The Executive Pulpit Should be Educational, Introspective, and Expansive

On June 8, 2020, Arvind Krishna made an adequate, necessary and articulate statement on racial bias, and he took a symbolic but non-bottom-line threatening stand on facial recognition. He could have done more. Because he leads an international organization, he should have addressed the international human condition. Unless he closed his eyes entering some critical countries with a significant IBM presence, he has seen, as I have, some horrendous worldwide conditions that explain why so many leave their homelands to come to the United States.

The pulpit of an international executive should be educational, introspective, and, especially, expansive—putting the human condition in any country within a worldwide context.

The pulpit of an international executive should be educational, introspective, and, especially, expansive—putting the human condition in any country within a worldwide context.

|

- Educational: Fear of Technology Is a Symptom of a More Concerning Issue |

As a technologist, Arvind Krishna should understand that a technology—in and of itself—is rarely, inherently evil. People don’t distrust the “what” of a technology as much as the “how.” Individuals who express a fear of technology, are usually expressing a fear of how a society or corporation, such as IBM, may use it. Fear of technology reaches way beyond facial recognition into every technological nook and cranny such as location services and the storing, accessing or outsourcing of a citizen’s personal information in another country. This mistrust is currently expressing itself against law enforcement, but the fear of technology reaches well beyond the justice system.

The complications that arise from a general fear of technology impact all possible technological advancements. Early automobiles without seat belts killed and maimed millions. Cars were not abandoned as a technology, but seatbelts eventually became mandatory. Hasn’t every technological advancement had its share of shortcomings? Shouldn’t business and government work together to address these shortcomings to gain its benefits? Isn’t this the definition of progress? Extracting the benefits from a technology is worth the risks if we move forward with an intelligent, cooperative effort. If IBM were trusted and transparent, wouldn’t society be comforted by its involvement in an industry-wide effort to standardize and install, figuratively speaking, face-recognition seat belts?

The businesses that are building these technologies are better equipped and staffed with expertise to offer industry-wide, failsafe options to protect individual liberties than any justice system. Businesses cooperating together at the industry level can enforce transparency and build trust. Today, industry leadership is failing to cooperate. In the case of facial recognition, when IBM withdrew, it abdicated its socio-technological responsibilities rather than stepping up to own them.

Every technology field needs credible and ethical individuals working within it, not abandoning the quest. Trying to stop technological advancements is like standing in front of a freight train and not expecting to get flattened. Ethical, like-minded individuals should be laying the tracks for, not lying on the tracks against, the conscientious use of a technology, and they should be the first to identify those who go off track … and lead the efforts to stop or wake them up because sometimes …

… even the best-of-the-best go off the rails.

The complications that arise from a general fear of technology impact all possible technological advancements. Early automobiles without seat belts killed and maimed millions. Cars were not abandoned as a technology, but seatbelts eventually became mandatory. Hasn’t every technological advancement had its share of shortcomings? Shouldn’t business and government work together to address these shortcomings to gain its benefits? Isn’t this the definition of progress? Extracting the benefits from a technology is worth the risks if we move forward with an intelligent, cooperative effort. If IBM were trusted and transparent, wouldn’t society be comforted by its involvement in an industry-wide effort to standardize and install, figuratively speaking, face-recognition seat belts?

The businesses that are building these technologies are better equipped and staffed with expertise to offer industry-wide, failsafe options to protect individual liberties than any justice system. Businesses cooperating together at the industry level can enforce transparency and build trust. Today, industry leadership is failing to cooperate. In the case of facial recognition, when IBM withdrew, it abdicated its socio-technological responsibilities rather than stepping up to own them.

Every technology field needs credible and ethical individuals working within it, not abandoning the quest. Trying to stop technological advancements is like standing in front of a freight train and not expecting to get flattened. Ethical, like-minded individuals should be laying the tracks for, not lying on the tracks against, the conscientious use of a technology, and they should be the first to identify those who go off track … and lead the efforts to stop or wake them up because sometimes …

… even the best-of-the-best go off the rails.

|

- Introspective: Even IBM “Went Off the Rails" |

Although Arvind referenced Watson Jr.’s quote concerning “race, color or creed” in his letter to Congress, he missed an opportunity to recognize that the corporation’s traditional founder fought ageism. In 1939, Tom Watson Sr., Dr. Norman Vincent Peale and Arthur Godfrey founded the “Forty Plus Club of New York.” This organization was an extension of the Sales Executive Club of New York and was founded to “combat the tendency of corporations to refuse to hire individuals over 40 years of age.”

There was a time when men, and at the time they were mostly men, were physically consumed by their family-supporting, labor-exhaustive burdens. Before the advent of steam and electric power, men were physically spent by their early forties from working in many labor-intensive, power-unassisted industries: coal mines, steel mills, lumbering, construction and farming. But this was a new age when individuals were capable of productive work past the age of forty, and Tom Watson Sr. (who was 65 at the time) spoke out and acted ethically in his changing world.

Unfortunately, the corporation has reverted in this area, and it needs to acknowledge and fix it. In this respect, Arvind Krishna missed an opportunity to put IBM back on the rails it laid eight decades earlier. A critical message should have been delivered: Fighting these human relation battles is a constant balancing act that requires good judgement and character, and even then, the best-of-the-best may stray off the tracks.

Human beings and the businesses they operate are never perfect and introspection is a characteristic of great leadership leading great companies.

There was a time when men, and at the time they were mostly men, were physically consumed by their family-supporting, labor-exhaustive burdens. Before the advent of steam and electric power, men were physically spent by their early forties from working in many labor-intensive, power-unassisted industries: coal mines, steel mills, lumbering, construction and farming. But this was a new age when individuals were capable of productive work past the age of forty, and Tom Watson Sr. (who was 65 at the time) spoke out and acted ethically in his changing world.

Unfortunately, the corporation has reverted in this area, and it needs to acknowledge and fix it. In this respect, Arvind Krishna missed an opportunity to put IBM back on the rails it laid eight decades earlier. A critical message should have been delivered: Fighting these human relation battles is a constant balancing act that requires good judgement and character, and even then, the best-of-the-best may stray off the tracks.

Human beings and the businesses they operate are never perfect and introspection is a characteristic of great leadership leading great companies.

|

- Expansive: International Executives Should Project International Perspectives |

Arvind Krishna missed an opportunity to call attention to human rights issues outside of the United States. He wrote that we should confront “discrimination in all its forms and wherever it exists.” In that respect, he could have mentioned two countries which contain larger percentages of the corporation’s workers than the United States: India and its Untouchables and China and its Muslim Uighur population. In the latter case, it is has been reported that, “Police raid homes, terrifying parents as they search for hidden children.” Of course it is much easier to call out such matters in the United States or India than it is in China. Taking a stand in the later, or even mentioning the Uighur issue in the press release, would have demonstrated a real stand of fortitude and courage.

Although the United States must keep making progress, we aren’t sterilizing our minority populations nor are we condemning their children to a life of cleaning toilets like China and India, respectively. In many cases, our restrooms are being cleaned by new immigrants. In the United States, they are simply the first generation putting their feet on the first rungs of society’s economic ladder. Every first-generation, immigrant family at one time or another from every nation of the world has had to start somewhere economically in this country. There is nothing ignoble in their work, and to suggest otherwise is patronizing.

The new immigrants within my own family, and those I chat with on a daily basis see a brighter future for their children. That is why they made the journey. They understand delayed gratification and are thankful to have left behind the fear they felt in their home countries. I tell them of my own history: scrubbing toilets with toothbrushes in the U.S. Army to pass the “white glove” commode test; flipping Whoppers and cleaning restrooms at Burger King to support my family while attending the University of Texas at Austin, and washing blood and guts off the walls of an Iowa Beef packing plant as a member of the company’s sanitation crew. We find our common bond.

I believe my stories leave them positive and hopeful of a better future for themselves, but especially for their children. (It is not the author’s intent to imply that all first-generation immigrants to this country start on the bottom economic rungs. In fact, some enter the workforce in the United States at an equivalent or higher economic rung than this author achieved after 50+ years of service, study and hard work in his own country. Such is life in a worldwide meritocracy—only a truly trustworthy international system of promotion makes this acceptable on the part of employees. The flight of top talent to the United States, though, is disconcerting within the countries that these individuals leave behind. Sometimes it is causing a healthy introspection: “Arvind Krishna as IBM CEO: Before we celebrate this as India's achievement, time to ask why talent leaves the country.”

Chief executives carry a heavier burden than any individual, though. They need to instill a belief in a better future on a national and international level and too many are coming up short. The United States has its problems, but the worldwide human condition has even more pressing issues which the leader of an international organization such as Arvind Krishna could have brought to everyone’s attention. He should have started, not just a U.S. centric discussion, but an international discussion. His words could have been more educational and expansive—and calming when falling on the ears within our country. The world needs the United States to stand for what is right and continue its progressive national and international human rights efforts—with determination and calm, not a hysteria that at times approaches levels of anarchy.

Overall, Arvind Krishna needs to project words and actions to simultaneously make our country’s citizens grateful for what they have, but also constantly uncomfortable with how much more we have yet to accomplish. Finding this path in both word and action supports democratic rule. In this respect, he did a better job than any of his twenty-first century predecessors, but it was a performance that fell short of great.

One gets the impression, though, that he has the potential for greatness. He has the international experience, the calm voice, the right direction, the presence, and seems able to express his heart in his writing.

The rest may come in time.

Although the United States must keep making progress, we aren’t sterilizing our minority populations nor are we condemning their children to a life of cleaning toilets like China and India, respectively. In many cases, our restrooms are being cleaned by new immigrants. In the United States, they are simply the first generation putting their feet on the first rungs of society’s economic ladder. Every first-generation, immigrant family at one time or another from every nation of the world has had to start somewhere economically in this country. There is nothing ignoble in their work, and to suggest otherwise is patronizing.

The new immigrants within my own family, and those I chat with on a daily basis see a brighter future for their children. That is why they made the journey. They understand delayed gratification and are thankful to have left behind the fear they felt in their home countries. I tell them of my own history: scrubbing toilets with toothbrushes in the U.S. Army to pass the “white glove” commode test; flipping Whoppers and cleaning restrooms at Burger King to support my family while attending the University of Texas at Austin, and washing blood and guts off the walls of an Iowa Beef packing plant as a member of the company’s sanitation crew. We find our common bond.

I believe my stories leave them positive and hopeful of a better future for themselves, but especially for their children. (It is not the author’s intent to imply that all first-generation immigrants to this country start on the bottom economic rungs. In fact, some enter the workforce in the United States at an equivalent or higher economic rung than this author achieved after 50+ years of service, study and hard work in his own country. Such is life in a worldwide meritocracy—only a truly trustworthy international system of promotion makes this acceptable on the part of employees. The flight of top talent to the United States, though, is disconcerting within the countries that these individuals leave behind. Sometimes it is causing a healthy introspection: “Arvind Krishna as IBM CEO: Before we celebrate this as India's achievement, time to ask why talent leaves the country.”

Chief executives carry a heavier burden than any individual, though. They need to instill a belief in a better future on a national and international level and too many are coming up short. The United States has its problems, but the worldwide human condition has even more pressing issues which the leader of an international organization such as Arvind Krishna could have brought to everyone’s attention. He should have started, not just a U.S. centric discussion, but an international discussion. His words could have been more educational and expansive—and calming when falling on the ears within our country. The world needs the United States to stand for what is right and continue its progressive national and international human rights efforts—with determination and calm, not a hysteria that at times approaches levels of anarchy.

Overall, Arvind Krishna needs to project words and actions to simultaneously make our country’s citizens grateful for what they have, but also constantly uncomfortable with how much more we have yet to accomplish. Finding this path in both word and action supports democratic rule. In this respect, he did a better job than any of his twenty-first century predecessors, but it was a performance that fell short of great.

One gets the impression, though, that he has the potential for greatness. He has the international experience, the calm voice, the right direction, the presence, and seems able to express his heart in his writing.

The rest may come in time.

The Author’s Opinion and Perspective

As one who remains forever hopeful, I pray that Virginia M. Rometty’s decision to make Arvind Krishna her successor is the exact opposite of Frank T. Cary’s decision to pick John R. Opel as his successor. In the latter case, a great chief executive officer who was exemplary in almost all his actions failed in one significant aspect—his choice of successor; while in the former case, a chief executive officer who failed at most everything, hopefully did one thing right—her choice of successor.

Arvind Krishna’s first quarter, though, felt like so many that the corporation has had since 1999. It could be too easily filed under “business as usual:” falling revenue, short-term profit thinking, earnings-per-share promises that produced roadkill without a roadmap, resource actions that cause generational battles and reduce productivity, cloud outages without explanation, and workload rebalancing that steals employment security from highly productive workers. All of this leads to the conclusion that sales productivity will continue its two-decade-long fall.

Arvind Krishna’s words were more articulate and more personal than any of his twenty-first century predecessors, but, in spite of the constant references to the principles of trust and transparency, the corporation’s, twenty-first-century obliqueness continued. There was still a significant disconnect between the words intended for an external audience, and the actions targeting the corporation’s internal supporting actors. Although many of the words reflected the character and concern of an FDR, the actions were lacking in most every other way. Fundamentally, because of the corporation’s internal human resource practices, it was business as usual—the same old stuff.

Arvind Krishna’s first quarter, though, felt like so many that the corporation has had since 1999. It could be too easily filed under “business as usual:” falling revenue, short-term profit thinking, earnings-per-share promises that produced roadkill without a roadmap, resource actions that cause generational battles and reduce productivity, cloud outages without explanation, and workload rebalancing that steals employment security from highly productive workers. All of this leads to the conclusion that sales productivity will continue its two-decade-long fall.

Arvind Krishna’s words were more articulate and more personal than any of his twenty-first century predecessors, but, in spite of the constant references to the principles of trust and transparency, the corporation’s, twenty-first-century obliqueness continued. There was still a significant disconnect between the words intended for an external audience, and the actions targeting the corporation’s internal supporting actors. Although many of the words reflected the character and concern of an FDR, the actions were lacking in most every other way. Fundamentally, because of the corporation’s internal human resource practices, it was business as usual—the same old stuff.

Arvind thinks and executes squarely at the intersection of business and technology.

Alex Gorsky, Chair of IBM Compensation Committee

To place IBM’s problems solely on the shoulders of its new chief executive would be a mistake. IBM’s Compensation Committee needs to return to the corporation’s early twentieth-century practice of paying its chief executive officers for real performance and then closely monitor that performance.

In Virginia M. Rometty’s eight years, a $1,000 investment lost her shareholders $56—including the reinvestment of dividends. She, and the board who paid her, failed to acknowledge the impact of her human resource practices on the corporation’s stakeholder ecosystem. Because of these practices, employees disengaged; therefore, the employees’ customers stopped buying; therefore, the shareholders were unimpressed with share buybacks, dividend increases and earnings-per-share metrics as revenues and profits drop by 28% and 41%, respectively.

This is the stakeholder chain reaction underlying her dismal shareholder performance. Yet, the Executive Compensation and Management Resources Committee paid her $158 million over these years of consistent non-performance.

In Virginia M. Rometty’s eight years, a $1,000 investment lost her shareholders $56—including the reinvestment of dividends. She, and the board who paid her, failed to acknowledge the impact of her human resource practices on the corporation’s stakeholder ecosystem. Because of these practices, employees disengaged; therefore, the employees’ customers stopped buying; therefore, the shareholders were unimpressed with share buybacks, dividend increases and earnings-per-share metrics as revenues and profits drop by 28% and 41%, respectively.

This is the stakeholder chain reaction underlying her dismal shareholder performance. Yet, the Executive Compensation and Management Resources Committee paid her $158 million over these years of consistent non-performance.

The compensation committee will need to decide if it will continue to enrich a corner office through meaningless metrics such as earnings per share which only encourages the accounting game of stock buybacks—exchanging one form of paper (greenbacks) for another type of paper (stocks); or will they design a compensation plan that will require the long-term building of profits through a major investment in people, processes and products. These latter type of investments will increase productivity which is the salesman- and saleswoman-in-chief’s way of increasing and stabilizing profitability.

|

Why can't today's CEOs who have social media platforms outperform FDR and a radio? . . . Credibility maybe?

|

If Arvind Krishna were a salesman, he would have held an FDR fireside-like chat with his employees on April 7, 2020 and said, “The human relations practices all of you have grown so accustomed to are, as of today, dead.”

The cheer—and spontaneous increase in productivity—would have been a “shout” heard around the world. In his first hundred days, he missed a great opportunity to start the “new machinery of a new deal” for his corporation’s employees, customers, shareholders, and their shared societies. |

This new machinery would have reversed the company’s twenty-first-century opaqueness. It would have included: publishing employee engagement numbers; publishing customer satisfaction numbers; publishing U.S. employment numbers like its competitors at Microsoft, Oracle, Cisco, Dell, Wipro, and HP; disclosing and halting age discrimination practices; and ending resource actions.