A Review of the "Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie"

|

|

Date Published: May 11, 2022

|

“Andrew Carnegie established a gospel of wealth that can be neither ignored nor forgotten and set a pace in distribution [of that wealth] that succeeding millionaires have followed as a precedent. In the course of his career, he became a nation-builder, a leader in thought, a writer, a speaker, the friend of workmen, schoolmen and statesmen, the associate of both the lowly and the lofty. But these were merely interesting happenings in his life as compared with his great inspirations – his distribution of wealth, his passion for world peace, and his love for mankind.

“Perhaps we are too near this history to see it in proper proportions, but … [Maybe] the generations hereafter may realize the wonder of it more fully than we of today.”

“Perhaps we are too near this history to see it in proper proportions, but … [Maybe] the generations hereafter may realize the wonder of it more fully than we of today.”

John C. Van Dyke, Editor’s Note, Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

A Review of "Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie" edited by John C. Van Dyke

- Reviews of the Day: 1920–21

- Observations of Andrew Carnegie from Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

- This Author’s Thoughts on Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

Reviews of the Day: 1920–21

|

“It is true that ‘truth is stranger than fiction.’ … In reading the life of Mr. Carnegie one is made to feel that here is unflinching fidelity to truth and yet it has all the glamour of romance. … We go with him into the factory, the telegraphy office, into the Civil War as an operator; we stand with him as he builds bridges; we rise with him step by step until he becomes the greatest iron master of this or any age. Boys, don’t fail to read it!”

“The Man Who Talks,” The Norwich Bulletin, November 20, 1920

“This story of the life of the Iron Master has been pronounced one of the three greatest autobiographies ever written. Like a romance from fairyland, it reads the narrative picturing the arrival of the poor Scots boy in America, his trials and struggles as messenger boy and laborer, his mastery of ‘little jobs that later became big jobs,’ and finally his triumph at the head of America’s greatest industry.”

“Autobiography of Carnegie,” The Oakland Tribune, December 8, 1920

|

“Andrew Carnegie will always live as the founder of the libraries for the people which bear his honored name. His first desire was for the diffusion of knowledge, and the betterment of democracy. And just as the future seemed brightening all around him, the war [World War I] came, and broke his heart. …

“The war shattered his hopes. It made him an old man at a blow [He was almost 80 at the time]. He saw hatred where he had looked for love, universal destruction where he had dreamed of the harvest of peace. For him it was the end of all things.

“But his work lives after him, and an example such as will never fail to inspire the hearts of men.”

“The war shattered his hopes. It made him an old man at a blow [He was almost 80 at the time]. He saw hatred where he had looked for love, universal destruction where he had dreamed of the harvest of peace. For him it was the end of all things.

“But his work lives after him, and an example such as will never fail to inspire the hearts of men.”

W. L. Courtney, “Books of the Day,” The Daily Telegraph, January 21, 1921

“In every way ‘The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie’ deserves a place among the great human documents of American literature, while its inspiration and wide range of appeal will make it of profound interest to readers who do not ordinarily enjoy autobiographies.”

“Forty-Three New Books,” The Santa Ana Daily Register, December 23, 1920

Observations of Andrew Carnegie from Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

|

- Carnegie on the stock market, Wall Street

“Nothing tells in the long run like good judgment, and no sound judgment can remain with the man whose mind is disturbed by the mercurial changes of the Stock Exchange. It places him under an influence akin to intoxication. What is not, he sees, and what he sees, is not. He cannot judge of relative values or get the true perspective of things. The molehill seems to him a mountain and the mountain a molehill, and he jumps at conclusions which he should arrive at by reason.

“His mind is upon the stock quotations and not upon the points that require calm thought.

“Speculation is a parasite feeding upon values, creating none.”

- Carnegie on corporate reputation

“A great business is seldom if ever built up, except on lines of the strictest integrity. A reputation for ‘cuteness’ and sharp dealing is fatal in great affairs. … It is essential to permanent success that a house should obtain a reputation for being governed by what is fair rather than what is merely legal.”

- Carnegie uses research and development to correct a mistake

“At a most critical period when it was necessary for the credit of the firm that the blast furnace should make its best product, it had been stopped because an exceedingly rich and pure ore had been substituted for an inferior ore – an ore which did not yield more than two thirds of the quantity of iron of the other. The furnace had met with disaster because too much lime had been used to flux this exceptionally pure ironstone. The very superiority of the materials had involved us in serious losses. …

“It was said by the proprietors of some other furnaces [competitors] that they could not afford to employ a chemist. … Looking back, … we were the first to employ a chemist at blast furnaces – something our competitors pronounced extravagant.”

This Author’s Thoughts on Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie is a wonderful self-written biography—full of life, hope and introspection. As Mr. John C. Van Dyke writes in his editor’s note, the editor has done little more “than arrange the material chronologically and sequentially” so that the narrative might run on unbrokenly to the end. Mr. Carnegie produced several books on his own and was extensively published in newspapers and magazines. He was a premier writer in his own right.

This is Andrew Carnegie writing about what is important to him and should be read in conjunction with Burton J. Hendrick’s The Life of Andrew Carnegie. The three chapters in the autobiography that stand out are, “The Homestead Strike,” “Problems of Labor,” and “The ‘Gospel of Wealth.’ ”

This is Andrew Carnegie writing about what is important to him and should be read in conjunction with Burton J. Hendrick’s The Life of Andrew Carnegie. The three chapters in the autobiography that stand out are, “The Homestead Strike,” “Problems of Labor,” and “The ‘Gospel of Wealth.’ ”

- Observations on Carnegie and the Homestead Strike

|

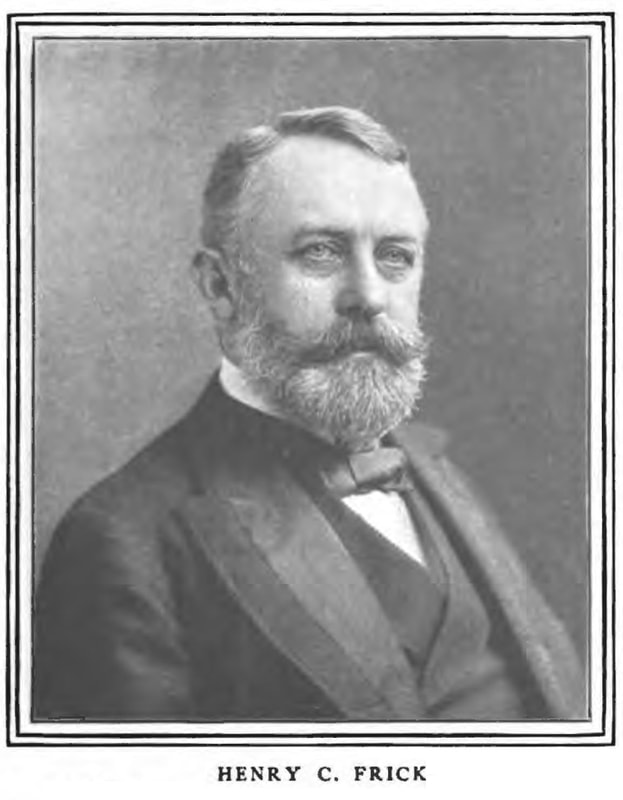

In writing about the Homestead Strike, Carnegie wrote that “no pangs remain of any wound received in my business career save that of Homestead. It was so unnecessary!” At the time, although he was the majority shareholder in the firm, he had turned over the running of the Carnegie Company “association” to Henry C. Frick as Chairman.

He was away in the Highlands of Scotland when the trouble began and did not get notice of what was happening until two days later. He wrote that, “Nothing I have ever had to meet in all my life, before or since, wounded me so deeply.” Andrew Carnegie finally ridded himself of Frick. It is an amazing story. Andy told him that the separation was a “divorce under ‘Incompatibility of Temper.’ ”

Carnegie’s respect for the rights of labor run throughout the autobiography. He was neither aloof to the concerns of his workers nor desiring to amass profits at their expense. His organization was known for its lack of “labor troubles” in an industry that was at the time wracked with violent conflicts between capital and labor.

|

The one time that Andrew Carnegie believed he picked the wrong man for the job, was Henry Frick in 1892. Charles Schwab replaced him.

|

He implemented a sliding scale so that his employees would share in the profits when times were good, but also provided for a “minimum wage” (Yes, he called it a “minimum wage.”) that sheltered his employees when times were bad for the industry as a whole.

Carnegie wrote the following to highlight how the sliding scale worked:

“It was a sliding scale based on the price of the product. Such a scale really makes capital and labor partners, sharing prosperous and disastrous times together. Of course, it has a minimum so that the men are always sure of living wages.”

|

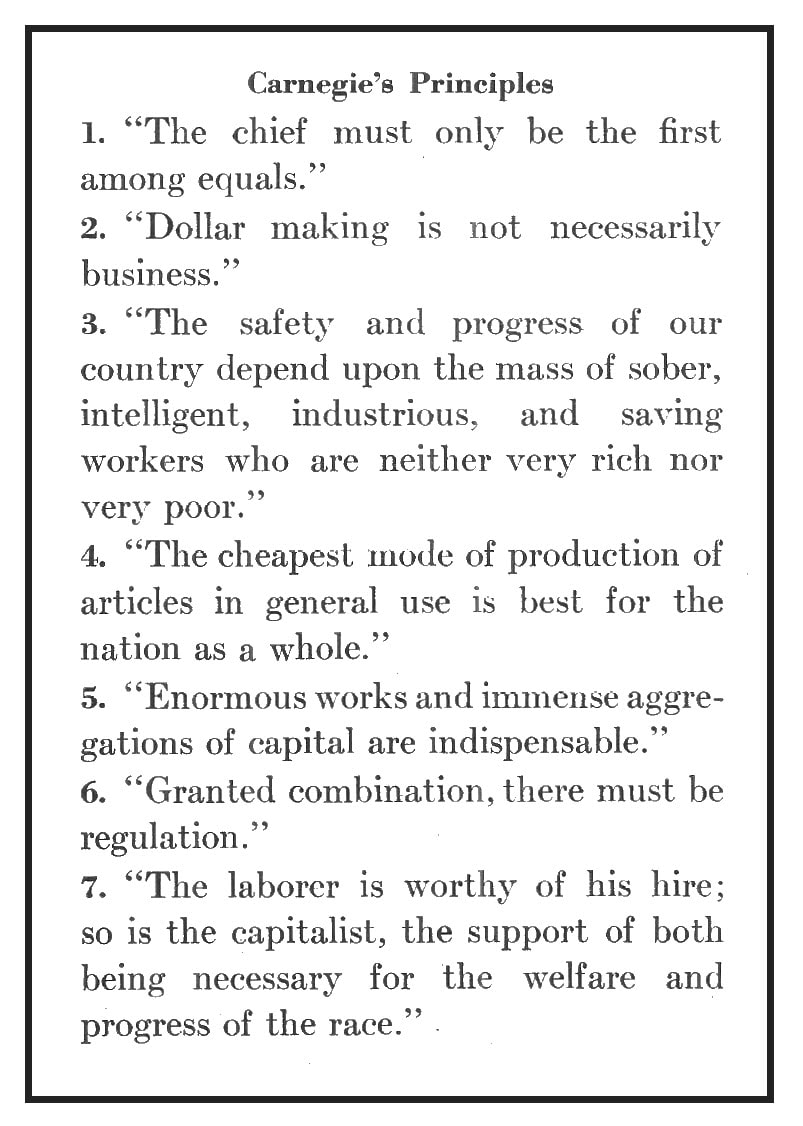

Andrew Carnegie’s business principles as highlighted by Charles Schwab in 1922.

|

The business was to operate conservatively and bear the burden of challenging times—not the employees. He believed that this sliding scale would enable the company to meet market demands, remain competitive, share profits between capital and labor, retain the best, highly-qualified workers, and maintain high productivity in the factories.

He believed that high wages were important but that such wages paled in comparison with steady employment. He was determined to ensure that he always had the best workers in his mills, and he provided consistent, uninterrupted employment that didn’t vary with the ups and downs of the steel industry to accomplish this. This is a highly commendable autobiography. Probably the single biggest issue this author has—after reading this autobiography, the biography by Burton J. Hendrick, and other sources about Andrew Carnegie—is that today’s “communal wisdom” too often fails in-depth research. The more knowledge a researcher gains in their studies, the more an individual realizes that such sites fail to provide expansive, accurate, unbiased educational information for forming personal opinions. |

Wikipedia details are all too often shallow, weak and subjective. This is dangerous for a democracy that depends on an intelligent and informed populace. Wikipedia information should be used as a starting point for research—not an end-all resource for informed decision making. The information provided on Wikipedia for the Homestead Strike is a case in point.

Read the chapters concerning this strike in these two books—this autobiography and B. J. Hendrick's biography, and then read Wikipedia – you will understand. . . .

. . . We are getting what we don't pay for.

Cheers,

- Pete

Read the chapters concerning this strike in these two books—this autobiography and B. J. Hendrick's biography, and then read Wikipedia – you will understand. . . .

. . . We are getting what we don't pay for.

Cheers,

- Pete