Ida M. Tarbell Overview, Introduction and Autobiography

|

|

Date Published: July 4, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

In my on-going research of Thomas J. Watson Sr., traditional founder of IBM, I found an exchange of letters between him and Miss Tarbell. She was inquiring about the percentage of women that were employed at IBM. Watson Sr. replied promptly with all the latest statistics that would make one think that the information was stored in an Excel spreadsheet awaiting her inquiry rather than a mechanical tabulating machine that would have required feeding punch cards to sort, consolidate and then print.

That led me to ask, "Who is Ida M. Tarbell?" Her name sure rang a bell. For several years now, I have gathered her books and become addicted to her writing style, her sense of justice, her wonderful desire to seek information at the source, and her outspoken stand for—not what others believed—but for what she believed. This article and the reviews of her books are the result of that reading.

Tom Watson invited her to the office in his reply with the information he provided. I wish I could have been present to hear that conversation. I am sure that Watson Sr. would have asked about her personal impressions of Elbert H. Gary, Owen D. Young, John D. Rockefeller Sr. and so many others that she interviewed and wrote about in her long journalistic career.

An amazing woman. An amazing human being.

That led me to ask, "Who is Ida M. Tarbell?" Her name sure rang a bell. For several years now, I have gathered her books and become addicted to her writing style, her sense of justice, her wonderful desire to seek information at the source, and her outspoken stand for—not what others believed—but for what she believed. This article and the reviews of her books are the result of that reading.

Tom Watson invited her to the office in his reply with the information he provided. I wish I could have been present to hear that conversation. I am sure that Watson Sr. would have asked about her personal impressions of Elbert H. Gary, Owen D. Young, John D. Rockefeller Sr. and so many others that she interviewed and wrote about in her long journalistic career.

An amazing woman. An amazing human being.

An Overview of Ida M. Tarbell and Her Works

|

Miss Tarbell wrote biographies on Elbert H. Gary (1925), the first chief executive of U.S. Steel, and Owen D. Young, chairman of the board of General Electric (1932). She authored a series of articles on the “Life of Napoleon” for McClure’s Magazine (1894), and she worked with a former Assistant Secretary of War, Charles A. Dana, ghostwriting his Recollections of the Civil War (1894). Her History of Standard Oil exposed to the public one of the most powerful and exploitative monopolies in American history (November 1902 - October 1904).

President Roosevelt branded her and her associates with the unique identifying moniker of muckraker because he believed they were only concerned with “debasing” and “the vile.” Although she did not like being classified a muckraker, she is recognized as one of first and most visible of the profession. |

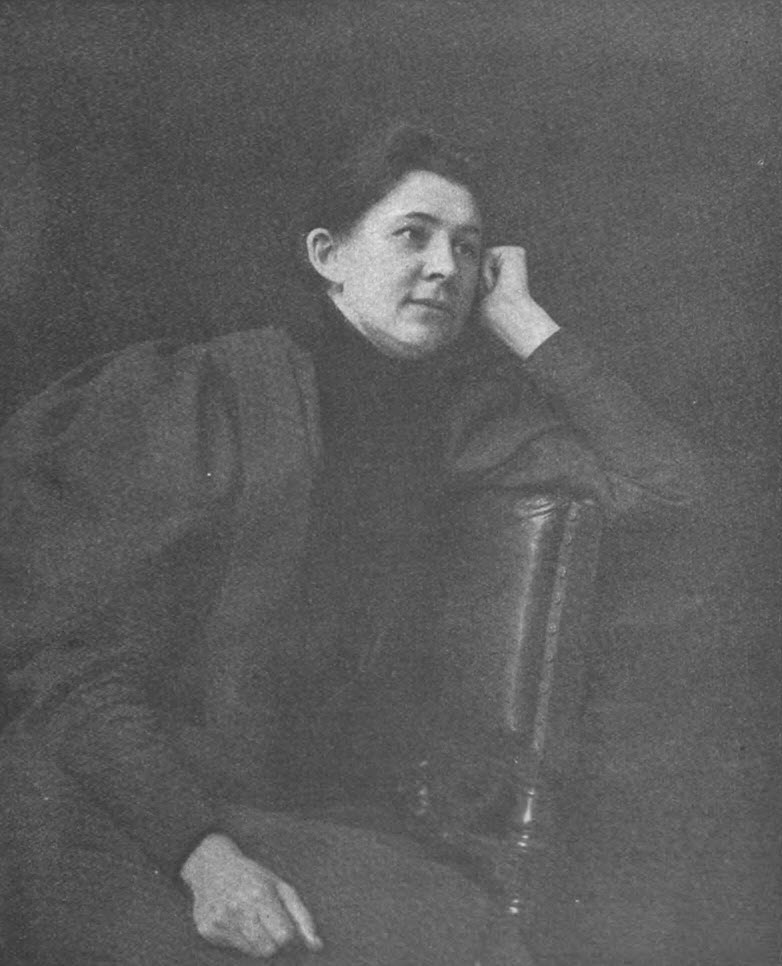

Ida Tarbell, 1898

|

A passage in Owen D. Young: A New Type of Industrial Leader expresses her frustration with being typecast in such a negative role. She closes the foreword with, “I have never been one who felt that the praise of him you believe to be a good man is a shame to a writer, any more than I have felt the condemnation of a man you believe evil is a particular virtue in a writer.” She called the concept of muckraking “stupid.” She felt that the profession eventually replaced a “passion for facts” with a “passion for subscriptions.”

But as the passage of time has shown, when Miss Tarbell captured, evaluated and wrote down her facts, she searched—not just for the worst in humanity—but also for the best. She believed it was her job to do both, and (as shown in the footnote) McClure’s Magazine’s subscriptions were the better for it. [See Footnote #1]

But as the passage of time has shown, when Miss Tarbell captured, evaluated and wrote down her facts, she searched—not just for the worst in humanity—but also for the best. She believed it was her job to do both, and (as shown in the footnote) McClure’s Magazine’s subscriptions were the better for it. [See Footnote #1]

|

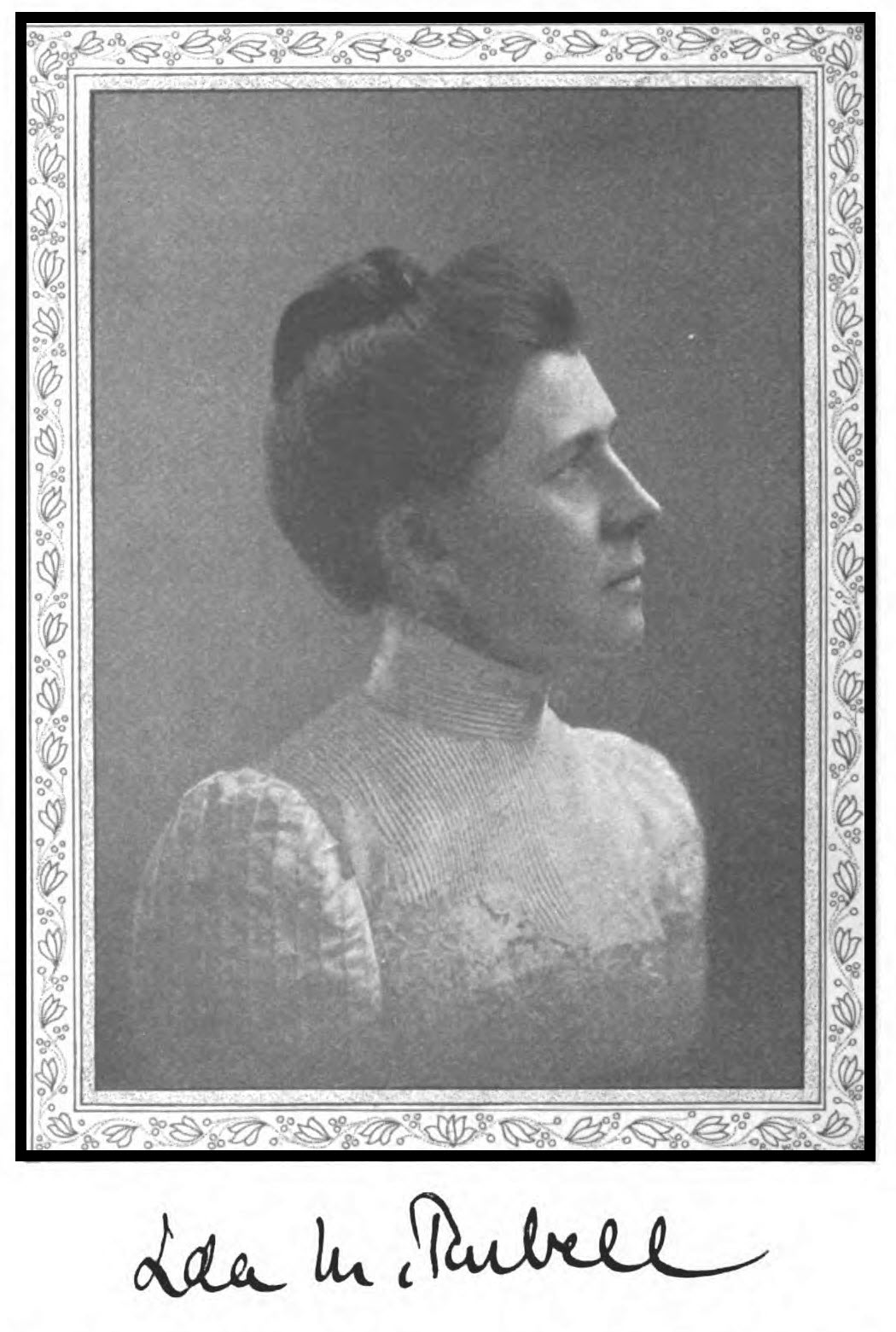

Ida M. Tarbell portrait, McClure's Magazine, October 1902

|

She was a hard woman. She focused her mind on the integrity of facts and in her writings, preserved for posterity what her disciplined and inquisitive intellect discovered. She applied the accountability of facts to what and about whom she wrote. The leadership of the suffragettes felt her pen’s pointed analysis. She never disagreed with or sought to hinder their long-term objective, but she found their tactics quite disagreeable: she openly challenged the movement’s leaders who painted women as victims with men as their eternal oppressors.

When others wrote that women had been forever oppressed, she wrote articles on some of the greatest women of the American Revolution of her day: Mercy Warren, Abigail Adams, Esther Reed, Mary Lyon, Catharine Beecher, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Success was not only within a persistent woman’s reach but, in many cases, had been achieved. She saw the leadership of the suffragette movement turn what should have been a forward movement for the combined male-and-female democratic masses into a divisive war of the sexes: it may have been tactically smart, but it was strategically wrongheaded. |

|

To her, the human spirit was the backbone of democracy. To implement a law without a long-term change of heart was promoting a change without a solid foundation because laws can never fully light a righteous path. Even the most just of laws are sadly ineffective in the hands of those with a pathetic, non-ethical compass.

This meant that the means were critical in achieving life-changing, long-term ends. She believed that to establish a lasting social change an informed mind must overturn a righteous heart’s wrongly-held convictions. It is the righteous heart guided by a right-thinking mind that must lead the way, not legalities or an over-zealous, counterbalancing extreme. Her simplest touchstone commandment was, “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you,” just as it was so many of America’s greatest 20th Century industrialists. As amazing as her prose was, she felt her calling was not as an author; as insightful as her speeches were, she never viewed herself as a gifted orator; but she was both a talented author and an insightful speaker because she remained faithful to her true calling: researcher. She mined data. She searched through dust-covered records on long-forgotten shelves, and critically assessed the insights of an all-to-fallible human recollection obscured by time or inflated by ego. |

Information spoke to her like few others of her day as she journeyed by train, canal barge, horse-drawn and horseless carriage to remote, small townships to decipher handwritten scribbles filled with misspellings.

|

She demonstrated the value of on-going research that incessantly sought and welcomed new knowledge. Her entire journalistic career she researched, wrote and published material about Lincoln: a series of articles over four years for McClure’s Magazine, several collections of finely-tuned biographical sketches such as a Boy Scouts’ Life of Lincoln (1922), multiple human-interest novellas such as A Reporter for Lincoln: The Story of Henry E. Wing (1927), and a four-volume masterpiece entitled The Life of Abraham Lincoln (1900).

Although Ida M. Tarbell delivered her message in a bygone century, it still carries a modern-day relevance. It is especially pertinent in a country where cynicism is creating a vast void between two types of its citizens: those who only see roadblocks everywhere, and those who overcome their individual roadblocks to achieve success. |

Ida M. Tarbell wrote from the Paris Peace Conference held after World War I the following about those she observed from the press who did not meet her standards:

One of the banes of the Paris Peace Conference was that there were so many men and women on the field under contract to write, to produce so many words every day or every week. There was no contract that these words should add something to the knowledge of the many things about which it was so necessary for men and women to learn—no contract that they should contribute by ever so little to the great need of control on every side, that they should comfort, soften hates, stimulate common sense.

Writers covered up their ignorance of things by doing prophecies, by shrieks of despair, by poses of intimacy with the great, by elaborately spun-out theories. They built up superstitions. They created things—absolutely created superstitions that may never be dispelled from the minds of those who read them back home.

Sound all too familiar? Hits too close to home, doesn't it? Do not despair; be forever hopeful; there is more to America than a superficial “passion for clicks” achieved through debasing and highlighting the vile.

Now for her autobiography: "All in the Day's Work."

Now for her autobiography: "All in the Day's Work."

A Review of "All in the Day's Work" the Autobiography by Ida M. Tarbell

|

- On challenges to her belief systems: "The heaviest blow to my self-confidence was my loss of faith in revolution as a divine weapon. ... I had held a revolution as a noble and sacred instrument, destroying evil and leaving men free to be wise and good and just. ... Now it seemed to me not something that men used, but something that used men for its own mysterious end and left behind the same relative proportion of good and evil as it started with.

- On freedom: "Freedom ... exists only in the spirit, never in human relations, never in human activities - the road to it [freedom] is as often as not what men call bondage."

A tremendous read for any woman or man interested in finding yourself in life and society. It comes with its turmoil. As for myself, may I write about human beings and its leadership as eloquently as Miss Tarbell. She is a tremendous example of respecting and growing one's talent.

Ida Tarbell added to the sum knowledge of mankind. She found balance in her articles. They stimulated discussion, thought, and common sense based on facts not hatred or superstitions; she, during her lifetime, wrote to enlighten her fellow mankind.

Fundamentally, she wrote to make the world a better place.

I hope you enjoy her works as much as I have.

They have made me a better person.

Cheers,

- Pete

Fundamentally, she wrote to make the world a better place.

I hope you enjoy her works as much as I have.

They have made me a better person.

Cheers,

- Pete

[Footnote #1] Ida M. Tarbell’s “Life of Napoleon” began in McClure’s Magazine in November 1894 and finished in April 1895 and was called by the magazine, “the most successful feature—by far. … Rarely, in all the course of magazine publication has there been a success equal to it.” It was surpassed a few months later by the “Early Life of Lincoln.” Ida Tarbell’s first article on Abraham Lincoln added more than 40,000 new subscribers within ten days of publication, and by the release of her third article, the series added a “clear increase” of 100,000.

This raised McClure’s Magazine’s subscriber base from 150,000 to 250,000 in just three months. Her series the “Life of Lincoln” started in November 1895 with “Abraham Lincoln” and appears to have ended with “Lincoln’s Funeral” published in September 1899.

This raised McClure’s Magazine’s subscriber base from 150,000 to 250,000 in just three months. Her series the “Life of Lincoln” started in November 1895 with “Abraham Lincoln” and appears to have ended with “Lincoln’s Funeral” published in September 1899.