THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition: Introduction

|

|

Date Published: June 4, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

Who are a corporation's major stakeholders?

The four major stakeholders in a corporation are customers, employees, shareholders, and their shared societies: (1) customers dedicate time, energy, and money to implement products; (2) employees exchange loyalty for rewarding careers; (3) shareholders invest for a return; and (4) society distributes the tax dollars of the first three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the business needs to optimize profits and operate in peace.

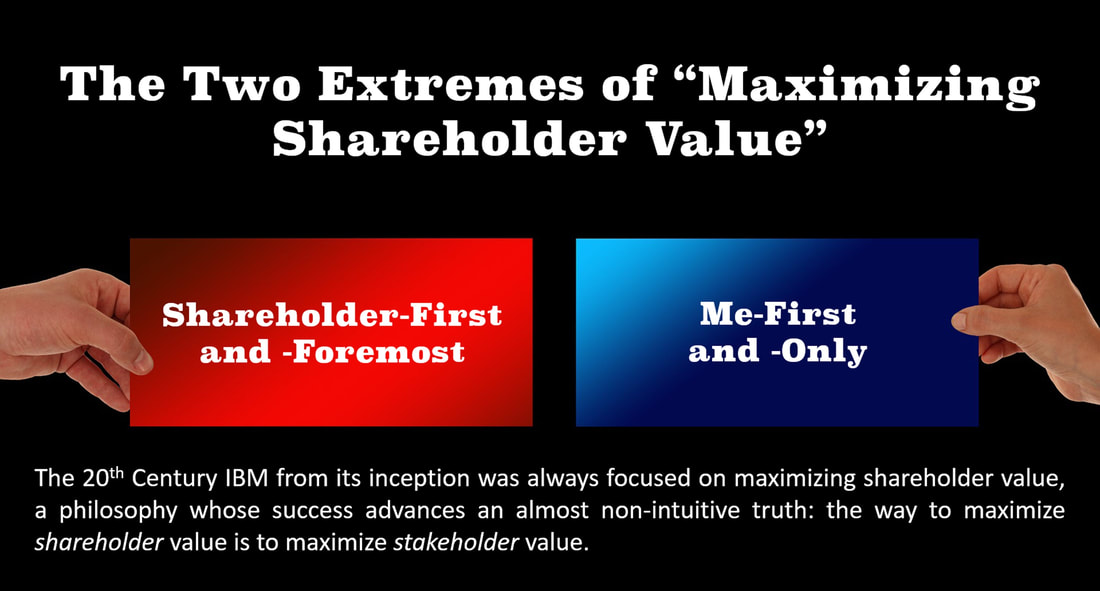

IBM’s history reinforces the fact that it isn’t necessarily the pursuit of maximizing shareholder value that is wrong, but that it is possible to take a wrong path in reaching for the goal.

Two of the wrong paths so evident with the 21st Century IBM are shareholder-first and -foremost, and me-first and -only

The four major stakeholders in a corporation are customers, employees, shareholders, and their shared societies: (1) customers dedicate time, energy, and money to implement products; (2) employees exchange loyalty for rewarding careers; (3) shareholders invest for a return; and (4) society distributes the tax dollars of the first three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the business needs to optimize profits and operate in peace.

IBM’s history reinforces the fact that it isn’t necessarily the pursuit of maximizing shareholder value that is wrong, but that it is possible to take a wrong path in reaching for the goal.

Two of the wrong paths so evident with the 21st Century IBM are shareholder-first and -foremost, and me-first and -only

Introduction to "The Rometty Edition" of THINK Again!

Introduction to THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition

- An Invitation to THINK Again

- The Extremes of Maximizing Shareholder Value

- Resisting the Extremes

- Capitulating to the Extremes

- Greed, not Profit, Increases Risk

An Invitation to THINK Again

Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM, is well-known for his corporation’s century-old, one-word imperative; desk placards, wall posters, and overhead signs instructed employees to THINK.

|

THINK was imprinted on custom leather notepads, notebooks, and briefcases.

Rodin’s The Thinker was the cover art on the first three issues of IBM’s corporate magazine that, for more than six decades, carried the brand THINK. This one-word directive was translated into every conceivable language, and eventually analysts, customers, and cartoonists considered it synonymous with IBM.

|

|

Thoughtful individuals are questioning the concept of maximizing shareholder value and its impact on a corporation’s stakeholders: its customers, employees, shareholders, and the societies they cohabit.

If Watson Sr. were alive today and asked to comment on IBM’s current executive strategy of maximizing shareholder value, he would look at the data, establish the facts, evaluate IBM’s current performance, extrapolate its possible futures, and say, “It is time to start thinking again.”

If Watson Sr. were alive today and asked to comment on IBM’s current executive strategy of maximizing shareholder value, he would look at the data, establish the facts, evaluate IBM’s current performance, extrapolate its possible futures, and say, “It is time to start thinking again.”

The Extremes of Maximizing Shareholder Value

In 1956, THINK Magazine clearly defined IBM’s stakeholders with the adage, “Business exists to provide a service to MAN—service to consumer man, to worker man, to investor man, and to the community of man.” To understand the extremes of shareholder value, it is necessary to walk in these men’s shoes. Doing so makes it easy to identify two extremes of shareholder myopia: a nearsighted focus on shareholder value to the exclusion of all else (better referred to as shareholder-first and -foremost) and the influence of individual greed under the guise of maximizing shareholder value (better called me-first and -only).

While we must be watchful of opposing extremes that could discourage capital investment in an economy, it is also necessary to be concerned with these out-of-bounds philosophies because they are prevalent.

While we must be watchful of opposing extremes that could discourage capital investment in an economy, it is also necessary to be concerned with these out-of-bounds philosophies because they are prevalent.

Resisting the Extremes

|

IBM from its inception has always been focused on maximizing shareholder value, a philosophy whose success advances an almost non-intuitive truth: the way to maximize shareholder value is to maximize stakeholder value.

Charles R. Flint combined three unique companies in 1911 for the express purpose of building a corporation that would always—no matter the economy—pay a dividend. But just a short three years later, Watson Sr. found the organization on the edge of bankruptcy, with the shareholders refusing to give up their dividends. When he took control, he made an immediate, drastic decision that saved the business: he stopped the quarterly payments. He did not believe in shareholder-first and -foremost; he believed in business-first. Then, in the Roaring Twenties, he prevented some elite, in-the-know shareholders from artificially boosting the price of the stock for a short-term gain. He also did not believe in me-first and -only. Watson Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps and maintained this balance. His goal was to deliver “attractive” returns to his shareholders, yet he borrowed from his shareholders to reinvest in people, processes, and products. |

Today’s shareholders would call his returns stellar, not attractive. In sixteen years, the number of shareholders grew by 2,000%.

Sometimes during periods of economic duress, social conflict, or natural disaster, the needs of the business—or one of the stakeholders—outweigh the needs of all others. There are examples in IBM’s history of employees sacrificing for the sake of their shareholders; shareholders providing money to rescue the corporation; customers giving a trusted vendor time to deliver the right technology; a chief executive officer reducing his commissions to provide employee benefits; and society defending the principles upon which the business and the country were both based. During such times, open communication between stakeholders ensured that individuals understood the necessity of any temporary imbalance, a discussion driven by IBM’s greatest chief executive officers.

These leaders understood that each stakeholder was invested in the corporation in their own way: customers dedicated time, energy, and money to implement products; employees exchanged loyalty for rewarding careers; shareholders invested for a return; and society distributed the tax dollars of all three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the business needed to optimize profits and operate in peace.

IBM’s history reinforces the fact that it isn’t necessarily the pursuit of maximizing shareholder value that is wrong, but that it is possible to take a wrong path in reaching for the goal.

Sometimes during periods of economic duress, social conflict, or natural disaster, the needs of the business—or one of the stakeholders—outweigh the needs of all others. There are examples in IBM’s history of employees sacrificing for the sake of their shareholders; shareholders providing money to rescue the corporation; customers giving a trusted vendor time to deliver the right technology; a chief executive officer reducing his commissions to provide employee benefits; and society defending the principles upon which the business and the country were both based. During such times, open communication between stakeholders ensured that individuals understood the necessity of any temporary imbalance, a discussion driven by IBM’s greatest chief executive officers.

These leaders understood that each stakeholder was invested in the corporation in their own way: customers dedicated time, energy, and money to implement products; employees exchanged loyalty for rewarding careers; shareholders invested for a return; and society distributed the tax dollars of all three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the business needed to optimize profits and operate in peace.

IBM’s history reinforces the fact that it isn’t necessarily the pursuit of maximizing shareholder value that is wrong, but that it is possible to take a wrong path in reaching for the goal.

Capitulating to the Extremes

|

IBM has also at times failed to meet shareholders’ expectations. Its failures prove that both shareholder-first and -foremost and me-first and -only are doomed strategies because they drive an imbalance in the stakeholder ecosystem that undermines the very existence of a business.

Frank Cary, during an economically frustrating decade, tried managing the stock price. The number of shareholders increased by over 25%, but the stock fell significantly further behind a benchmark large company index. John Opel, in his four-year tenure, tried financial engineering—following a short-term, financially expedient path at the expense of the long-term health of the business. When Opel’s “engineering” reached its all-too-predictable end, one out of every three shareholders abandoned the company. Then his successor blamed the employees rather than a failure of leadership. |

Now another set of IBM CEOs has lost sight of the best path. They have followed two five-year roadmaps with the express vision of maximizing shareholder value. A decade and a half of data proves these roadmaps used the wrong guideposts. Since 1999, IBM’s measurements of productivity have been flat or in decline, and have fallen precipitously behind its competition. It is, once again, relying on financial engineering, and its habitual investment in paper is overriding the long-term necessity of a business to make people more productive, processes more effective, and products more valuable.

Greed, not Profit, Increases Risk

|

Watson Sr. called capitalism “an opportunity for ability.” Capitalism rewards an individual for individual results. It rewards some individuals out of proportion to others based on many factors, including profession, education, job responsibility, business acumen, or even raw physical endowments. There are individuals who will seek advantage through these imbalances, and because of this, an economic system motivated by profit can easily become a breeding ground for me-first and -only strategies. Individuals who game the system will argue that it is their legal (and sometimes even their ethical) right to gather all the profits they possibly can unto themselves.

However, if greed is permitted to reign supreme, profit is the single word used to capture all that is wrong with a capitalist economy. While capitalism is based on profits, profit does not equal greed. The proper distribution of profits funds future economic growth, pays wages, enables retirements, rewards educational advancements, builds new leading-edge products, ensures quality service, and economically stabilizes the political system chosen by a society’s citizens. |

It is the obligation of capitalists who understand how tenuous the bond is between economic and social systems to stand in opposition to all destructive philosophies, and to stand especially strong when capitalism takes on self-destructive tendencies. They must support a system of checks and balances between their economic and social systems because greed will not only destroy a properly functioning economic system, it will betray its supportive social system.

Greed, it could be argued, is the unifying thread in Winston Churchill’s statement comparing capitalism and socialism: “The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings. The inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.”

Democracy is a rowdy social system for discussing such inequities. When its system of checks and balances is in operation, it isn’t always the most beautiful conversation to behold—especially when the combatants show little respect for each other. But until we discover a better way, the best combination of political and economic systems is democracy and capitalism because they both place responsibility for action on the individual.

Greed, it could be argued, is the unifying thread in Winston Churchill’s statement comparing capitalism and socialism: “The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings. The inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.”

Democracy is a rowdy social system for discussing such inequities. When its system of checks and balances is in operation, it isn’t always the most beautiful conversation to behold—especially when the combatants show little respect for each other. But until we discover a better way, the best combination of political and economic systems is democracy and capitalism because they both place responsibility for action on the individual.