Sarah Schuyler Butler's Perspective on "Women as Citizens"

|

|

Date Published: May 11, 2023

|

This article on “Women as Citizens” is outstanding in its probing questions the author asks that could easily be applied to many of today’s issues—beyond women.

I discovered this article—as always—in my research on Thomas J. Watson. Sarah Schuyler Butler is the daughter of Nicholas Murray Butler who was one of Tom Watson’s closest friends and confidants. Sarah Butler is writing in 1924, four years after women had received the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment. Her questions are straight forward. The insights she displays in her answers, even more so.

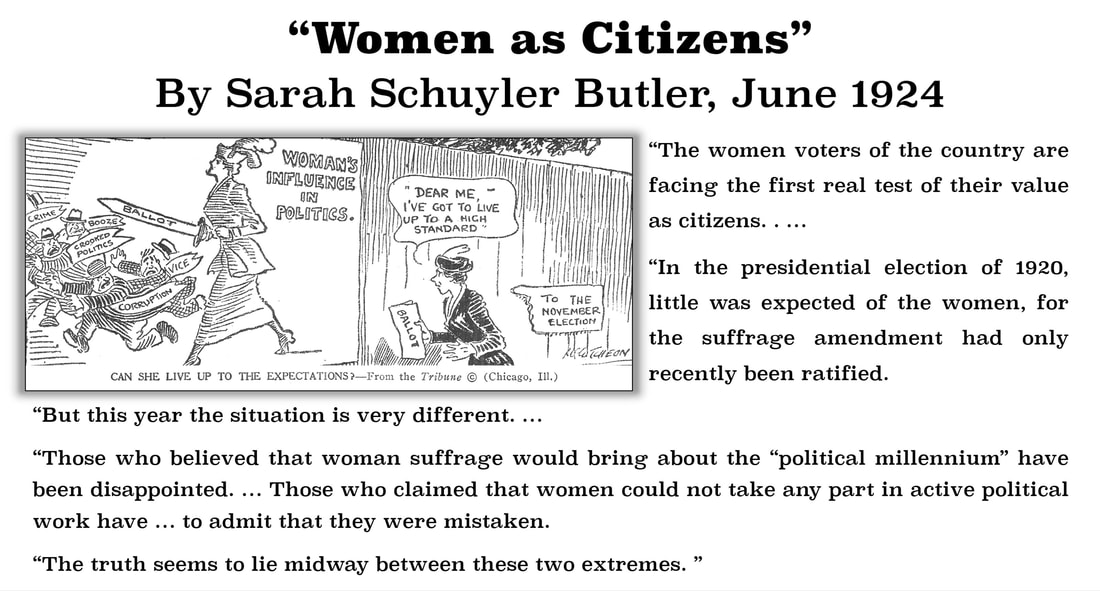

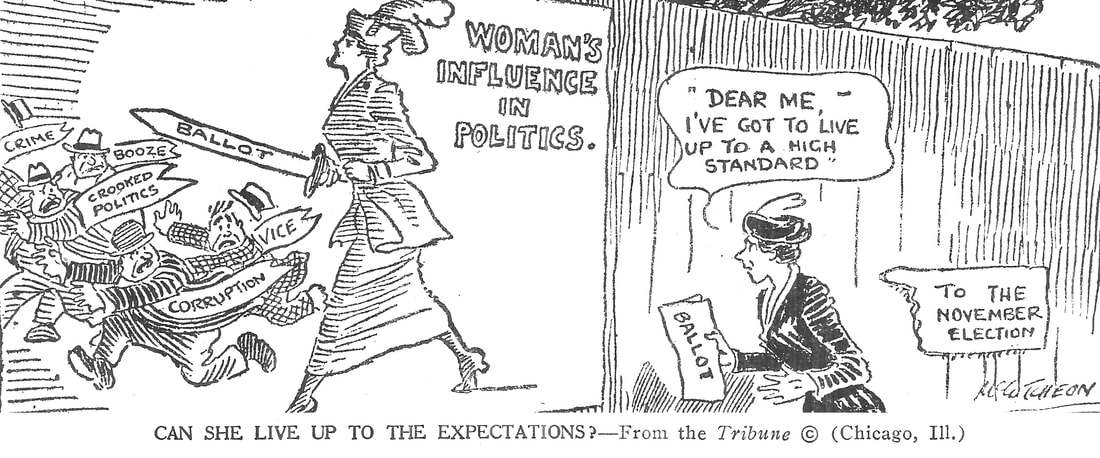

Occasionally information was added for clarity. These additions are within [brackets]. At times, this author wanted to add emphasis to points in Sarah Schuyler Butler’s article. This emphasis is added with an underline. All images except the last one at the end of the article were added. They are marked with the year of publication to indicate that all images inserted into this article are in the public domain because they were printed before January 1, 1928. Headings were added or modified by this author.

This is republished In the hope that we may learn from the past and avoid repeating the same failures today as yesterday. Whether it is issues involving women, men, white, black, Latino, Asian, LGBTQ+, black reparations, or some other issue, these are the type of intelligent questions that need thoughtful channeling through such emotional issues to find the balance—and long-term results, in a political implementation.

I discovered this article—as always—in my research on Thomas J. Watson. Sarah Schuyler Butler is the daughter of Nicholas Murray Butler who was one of Tom Watson’s closest friends and confidants. Sarah Butler is writing in 1924, four years after women had received the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment. Her questions are straight forward. The insights she displays in her answers, even more so.

Occasionally information was added for clarity. These additions are within [brackets]. At times, this author wanted to add emphasis to points in Sarah Schuyler Butler’s article. This emphasis is added with an underline. All images except the last one at the end of the article were added. They are marked with the year of publication to indicate that all images inserted into this article are in the public domain because they were printed before January 1, 1928. Headings were added or modified by this author.

This is republished In the hope that we may learn from the past and avoid repeating the same failures today as yesterday. Whether it is issues involving women, men, white, black, Latino, Asian, LGBTQ+, black reparations, or some other issue, these are the type of intelligent questions that need thoughtful channeling through such emotional issues to find the balance—and long-term results, in a political implementation.

Peter E. Greulich, May 2023

Women as Citizens

by Sarah Schuyler Butler

(Chairman of the Republican Women’s State Executive Committee in New York)

[From The American Review of Reviews, June, 1924, Edited by Albert Shaw]

(Chairman of the Republican Women’s State Executive Committee in New York)

[From The American Review of Reviews, June, 1924, Edited by Albert Shaw]

|

|

Women Are Facing Their First Real Electoral Test

The women voters of the country are facing the first real test of their value as citizens.

|

Public opinion is by no means decided as to whether or not woman suffrage has been of benefit to America; and the number of articles in magazines and newspapers devoted to a discussion of the success or failure of women as voters proves conclusively that the question is arousing wide-spread interest.

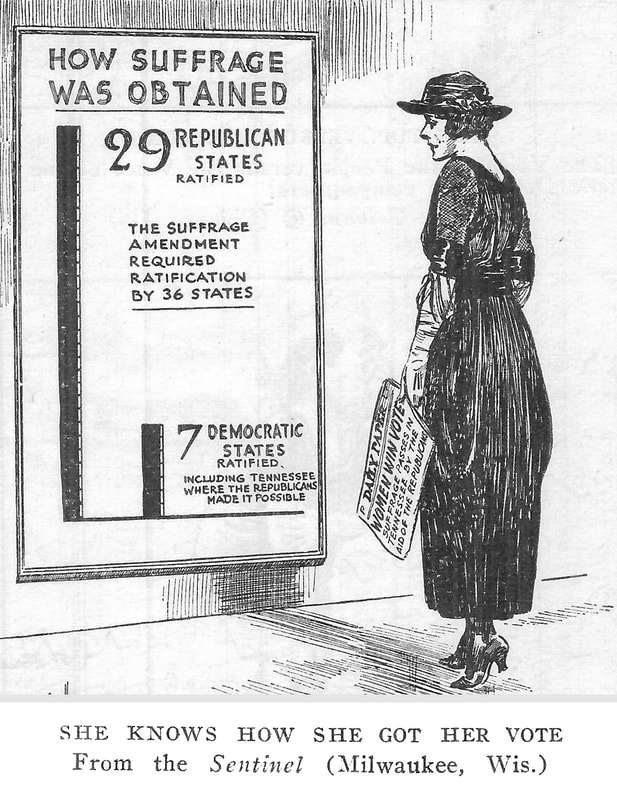

In the presidential election of 1920 little was expected of the women, for the suffrage amendment had only recently been ratified. But this year the situation is very different. Politicians everywhere are agreed that the women voters may be the deciding factor in the election, and for that reason they are watching them with unusual interest. Of course we are still new to politics. Four years is a short time in which to educate women in political methods, and to give them an intelligent understanding of the problems of government. With our new opportunities have come new conditions and new responsibilities, and we are only gradually learning to a adapt ourselves to them. |

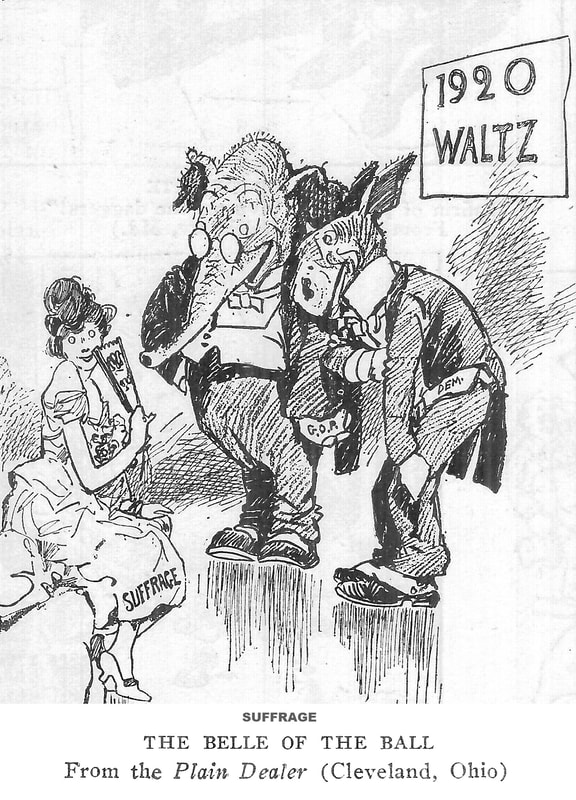

Review of Reviews, April 1920

|

The Women’s Suffrage Movement Is Not a Failure

Woman suffrage is certainly not a failure; it has not done away with all the faults of politics and of politicians, nor is there any reason why such a result should have been expected.

The American Review of Reviews, November 1920

Much has been accomplished in the last four years in teaching women to understand their responsibility as citizens; but there is much work still to be done, and there are many groups of women whom, so far, the political parties have not been able to reach.

The average woman voter suffers from a handicap which is the natural result of her training. In the days before the granting of the suffrage, certain civic problems were set aside as women’s province. Education, charity, public health, and various kinds of welfare were generally regarded as subjects in which women should interest themselves, and they were urged to confine their activities to this field.

The result was that they grew to regard themselves as the advocates and supporters of special causes, and to think of the broader questions of constitutional government and political policy as matters in which they were not particularly concerned.

The average woman voter suffers from a handicap which is the natural result of her training. In the days before the granting of the suffrage, certain civic problems were set aside as women’s province. Education, charity, public health, and various kinds of welfare were generally regarded as subjects in which women should interest themselves, and they were urged to confine their activities to this field.

The result was that they grew to regard themselves as the advocates and supporters of special causes, and to think of the broader questions of constitutional government and political policy as matters in which they were not particularly concerned.

Welfare Issues Taking Women's Natural Interest

This tendency, which is wide-spread, has been encouraged—often unconsciously—by many women who were formerly ardent suffrage workers. They became so accustomed to working with women and for women, and to taking it for granted that men were opposed to them, that they now find it difficult to bear their share of the equal political partnership for which they fought so long.

They may join a political party, but their deepest interest seems to center in organizations composed exclusively of women and dealing primarily with the special causes I have mentioned above.

A prominent member of the Assembly of New York State told me last autumn that in his ten years or more of legislative experience he had never received a communication from women or women’s organizations except on bills which could be classified as “welfare legislation.” And only last winter when a committee of women proposed to take up the Mellon Tax Reduction Plan as a subject for study and discussion, one of its members vigorously protested on the ground that “all the men’s organizations are supporting that, so there is no necessity for women to do so.”

They may join a political party, but their deepest interest seems to center in organizations composed exclusively of women and dealing primarily with the special causes I have mentioned above.

A prominent member of the Assembly of New York State told me last autumn that in his ten years or more of legislative experience he had never received a communication from women or women’s organizations except on bills which could be classified as “welfare legislation.” And only last winter when a committee of women proposed to take up the Mellon Tax Reduction Plan as a subject for study and discussion, one of its members vigorously protested on the ground that “all the men’s organizations are supporting that, so there is no necessity for women to do so.”

Single Issue Voting and Political Intolerance

This deep interest of many women in special causes often leads to the most bitter intolerance on their part. They are very apt to judge a candidate’s fitness for office by his attitude towards some one question in which they are interested.

So we have the distressing spectacle of women in both great parties actively opposing candidates for office whose record is excellent, and whom they criticize only because they refused to vote for woman suffrage five years ago. The same type of woman frequently threatens to leave, and sometimes does leave, a political party because of its failure to pass or to defeat a particular bill. One might just as well propose to give up church membership because one does not approve of some statement made by the minister in the course of his sermon.

So we have the distressing spectacle of women in both great parties actively opposing candidates for office whose record is excellent, and whom they criticize only because they refused to vote for woman suffrage five years ago. The same type of woman frequently threatens to leave, and sometimes does leave, a political party because of its failure to pass or to defeat a particular bill. One might just as well propose to give up church membership because one does not approve of some statement made by the minister in the course of his sermon.

|

This same feminist point of view is manifested in another way.

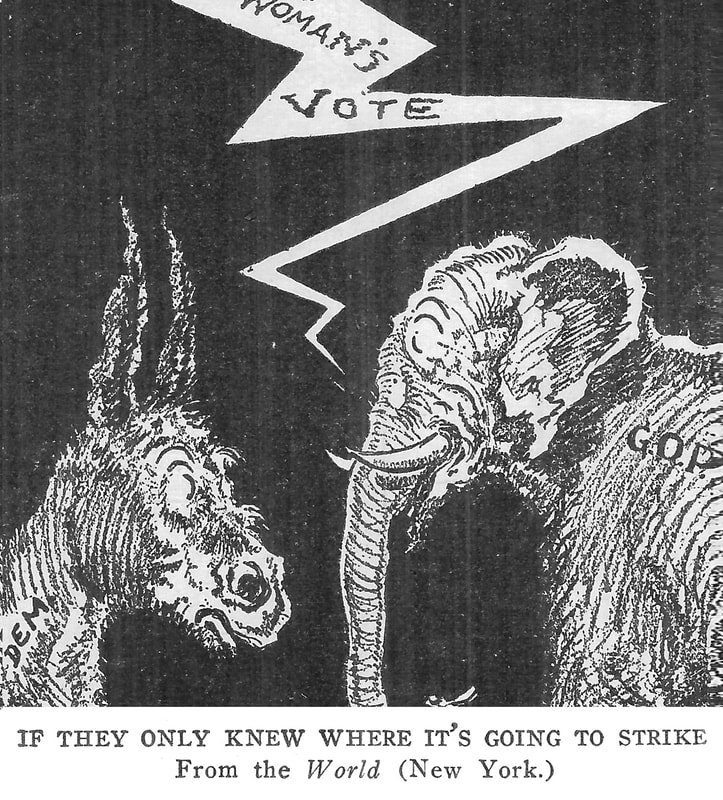

There is a continual demand from certain groups of women for women candidates—a demand too often based, not on any peculiar qualifications for the office under discussion, but simply on the fact that “women should be represented.” And here we are faced by a serious problem, which lies at the base of the whole question of woman suffrage. Are women going to continue to lay emphasis on their sex? Is there to be a woman’s vote? Are we to have women’s bills, no men’s causes, and women’s representatives? Or are the women voters of the country going to regard themselves as citizens, bearing their share of political responsibility, doing their share of political work, and receiving their share of political honors and political representation because they have deserved and earned them, rather than merely because they are women? |

Perle Mesta, Minister to Luxembourg proved herself.

|

There Should Be No Reason for a “Woman’s Vote”

The idea that there is and should be a “woman’s vote” is fostered by many women and by some politicians; but it is difficult to see how such a thing could exist under our social system.

In America the family is fortunately still the unit of society. Since this is so, it is presumably true that the members of a given family have more or less common interests and common beliefs. It is a natural result, therefore, that a woman’s vote, like a man’s, should be determined partly by her training and traditions and partly by her interests and her environment.

In America the family is fortunately still the unit of society. Since this is so, it is presumably true that the members of a given family have more or less common interests and common beliefs. It is a natural result, therefore, that a woman’s vote, like a man’s, should be determined partly by her training and traditions and partly by her interests and her environment.

Since all women have neither the same training and traditions, nor the same interests and environment, it would seem unreasonable and undesirable for them to vote as a unit. If they are intelligent, their point of view will vary; and the particular problems of government which affect them most will differ, according to the part of the country in which they live or the type of work in which they or their families are engaged. It is undoubtedly for this reason that the majority of women vote as the men members of their families vote.

It is also true that in the majority of cases where there are two or more men in a family they vote alike. And one condition is just as natural and just as desirable as the other. There is no more reason why there should be a woman’s vote than why there should be a man’s vote. And there is none. For, although there are millions of women voters in America, so far, they have shown no tendency to vote as a unit.

As a matter of fact, if women ever do vote as a unit our whole system of government will be automatically overthrown. We live under the two-party system—the only system which provides for a definite shouldering of public responsibility. Our division into political parties has been based on a difference of opinion as to certain fundamental principles of government, and each of the two great parties counts among its members men and women of every shade of opinion and of every rank in society.

The fact that our political parties divide our population vertically, and that each one of them is a fair cross-section of the American people, has been one of our greatest blessings. We are fortunate enough to have escaped political division by classes.

Let us hope that we may also be fortunate enough to escape political division by sex.

It is also true that in the majority of cases where there are two or more men in a family they vote alike. And one condition is just as natural and just as desirable as the other. There is no more reason why there should be a woman’s vote than why there should be a man’s vote. And there is none. For, although there are millions of women voters in America, so far, they have shown no tendency to vote as a unit.

As a matter of fact, if women ever do vote as a unit our whole system of government will be automatically overthrown. We live under the two-party system—the only system which provides for a definite shouldering of public responsibility. Our division into political parties has been based on a difference of opinion as to certain fundamental principles of government, and each of the two great parties counts among its members men and women of every shade of opinion and of every rank in society.

The fact that our political parties divide our population vertically, and that each one of them is a fair cross-section of the American people, has been one of our greatest blessings. We are fortunate enough to have escaped political division by classes.

Let us hope that we may also be fortunate enough to escape political division by sex.

Women Are Breaking Down Old Prejudices

|

In the last four years much progress has been made.

In the early days of their enfranchisement the women were mainly concerned with perfecting their organization, obtaining representation on the chief party committees, and trying to induce the men politicians to heed their expressions of opinion on party policies. Those were the days of breaking ground, of establishing precedents, and of obtaining the recognition which the women of both great parties now enjoy. |

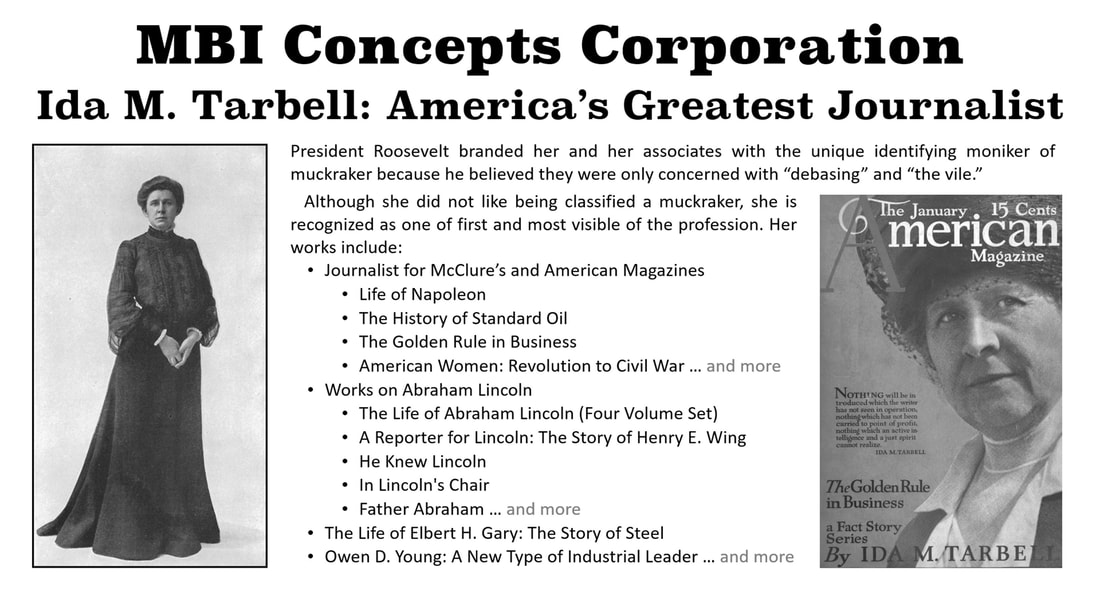

Ida M. Tarbell had similar insights into militant suffragettes: the goal was right, the tactics were wrong.

|

They were also the days of many and bitter antagonisms, and often of a spirit of hostility between men and women in the parties. This was necessarily so, for there had been much opposition to woman suffrage. And many men were not in the least willing to share their power with women. It was a natural and a very human reaction. None of us like to give up our prerogatives until we are forced to do so; and during the time that women regarded themselves as on sufferance [the suffering or undergoing of something bad or unpleasant], force was the weapon they most often employed.

But that time is now, happily, past. The foundations have been laid, and although there is much for us still to do, it must be done not by force, but by persuasion; not by hostility, but by cooperation. The average male politician realizes that women in the political parties have come to stay, and he is beginning to see that they may be a valuable asset. But he is frankly disgusted by those women who talk of equal representation and equal opportunity but continually seek special privileges.

When women do those things, they undermine the whole argument in favor of woman suffrage. Women asked for the vote on the ground that they were just as capable of being good and intelligent citizens as men were. Yet, now that the vote has been given to them, they are all too apt to think of themselves as women first, and only secondarily to consider their duty as citizens. There is too much of the old spirit of antagonism still.

I remember distinctly hearing a woman who had been active in the campaign for suffrage and is now a prominent party worker, severely criticize another woman because she did not give the members of a committee certain information which she had received in confidence from male leaders of the party.

This incident merely serves to illustrate the fact that the attitude of the militant suffragist frequently appears when we least expect it. Even among party workers there is still a tendency to mutual suspicion and distrust, which must be overcome before women can take their full share of the burden of work and responsibility.

But that time is now, happily, past. The foundations have been laid, and although there is much for us still to do, it must be done not by force, but by persuasion; not by hostility, but by cooperation. The average male politician realizes that women in the political parties have come to stay, and he is beginning to see that they may be a valuable asset. But he is frankly disgusted by those women who talk of equal representation and equal opportunity but continually seek special privileges.

When women do those things, they undermine the whole argument in favor of woman suffrage. Women asked for the vote on the ground that they were just as capable of being good and intelligent citizens as men were. Yet, now that the vote has been given to them, they are all too apt to think of themselves as women first, and only secondarily to consider their duty as citizens. There is too much of the old spirit of antagonism still.

I remember distinctly hearing a woman who had been active in the campaign for suffrage and is now a prominent party worker, severely criticize another woman because she did not give the members of a committee certain information which she had received in confidence from male leaders of the party.

This incident merely serves to illustrate the fact that the attitude of the militant suffragist frequently appears when we least expect it. Even among party workers there is still a tendency to mutual suspicion and distrust, which must be overcome before women can take their full share of the burden of work and responsibility.

There Are Issues of Primary Interest to Women

|

I would not under any circumstances deny that there are certain subjects in which women have a primary interest and on which they are particularly qualified to speak.

Any question which affects women and children must be of vital concern to every one of us, but women must be sure that they consider these questions as citizens and not merely as women, and that the remedies or solutions they propose are consistent with our American form of government. In other words, we should view these subjects not as isolated units, but as a part of the whole governmental and legislative problem. It is only when we take this attitude that we can be sure that our advice is sound, and that we are benefiting the community as a whole rather than any single group, however worthy and deserving that group may be. |

The American Review of Reviews, October 1920

|

We must also admit that women’s committees are still necessary in political parties. We all look forward to the day when men and women will work together without any need of special representation or consideration, but at present there are many hundreds of thousands of women who have not been aroused to a consciousness of their political responsibility, and who are more easily reached and influenced by other women than by men.

There is, however, a constant effort to lessen the emphasis on sex, and to bring about close cooperation between men and women workers in the political parties.

There is, however, a constant effort to lessen the emphasis on sex, and to bring about close cooperation between men and women workers in the political parties.

Women's Accomplishments of the Last Four Years

|

On the whole, in looking back over the last few years, an impartial observer would find much encouragement in the political progress made by the women of the country. They have “won their spurs.” They have been given a place on party committees, and they are taking an ever-increasing share in party councils.

The women who pride themselves on being non-partisan are gradually finding out that the only way in which any citizen can be politically articulate is to join a party. This is a difficult lesson for many women to learn, and some of them have had to suffer bitter disillusionment in learning it. The advocates of special causes have discovered that without the help of the women within the parties they can make little progress, and many of them have become active party workers in consequence. Out of their disillusionment much good will come, for they bring to the party of their choice enthusiasm and a passionate determination to accomplish certain things. |

The American Review of Reviews, October 1920

|

Their party associations teach them the value of fundamental political principles, the necessity for following established forms of procedure; and their fellow-workers give them both inspiration and practical training. This combination leads to a more human attitude on the part of the political parties, and a greater and more sound appreciation of our system of government on the part of the women.

But the structure of good citizenship cannot be built in a day. There are many women who have never assumed their civic responsibilities. They must be sought out and induced to take their places among the ranks of America’s working citizens. We must help the average woman to overcome her tendency to confine her interest to special causes, and we must show her the wide field of public service that lies open to her.

Especially we must learn the meaning of cooperation within the parties. The energy that men and women have worked up in mutual antagonism must be turned to a common effort to serve the community and the cause of good government.

But the structure of good citizenship cannot be built in a day. There are many women who have never assumed their civic responsibilities. They must be sought out and induced to take their places among the ranks of America’s working citizens. We must help the average woman to overcome her tendency to confine her interest to special causes, and we must show her the wide field of public service that lies open to her.

Especially we must learn the meaning of cooperation within the parties. The energy that men and women have worked up in mutual antagonism must be turned to a common effort to serve the community and the cause of good government.

Political Maturity Will Bring Successes

|

Just so long as the women voters of the country must be given special privileges; just so long as they must be offered special programs to attract them, as one offers sweets to a child; just so long as they demand special representation based on sex; just so long as they allow political parties to consider them as a unit rather than as intelligent and patriotic individuals—so long do they prove that women have not yet reached their political maturity.

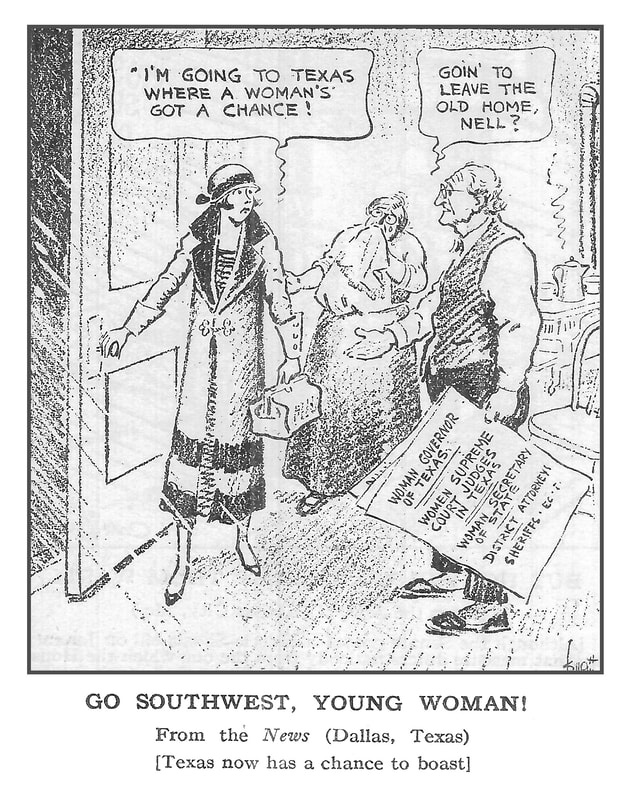

Political parties and candidates for office should be able to make their appeal, not to men or to women as such but to intelligent, high-minded, public-spirited citizens regardless of sex. When women voters learn to think of themselves in that spirit, woman suffrage in America will have been proved a complete success. Women have a real contribution to make to our political life. They bring to it a new enthusiasm, a fresh point of view, and a confirmed faith in the value of high ideals. They are not easily discouraged, and those of them who are genuinely interested in politics are willing to give unsparingly of their time and strength. |

Women making progress in Texas politics. This cartoon appeared in the February 1925 issue of The American Review of Reviews.

|

When they learn to merge their sex in citizenship, a great advancing step will have been taken.

In 1920 women had just been enfranchised. In 1924 we are facing a crucial test. Let us meet that test so that in 1928 the success of woman suffrage will be a subject not for debate but for congratulation.

In 1920 women had just been enfranchised. In 1924 we are facing a crucial test. Let us meet that test so that in 1928 the success of woman suffrage will be a subject not for debate but for congratulation.

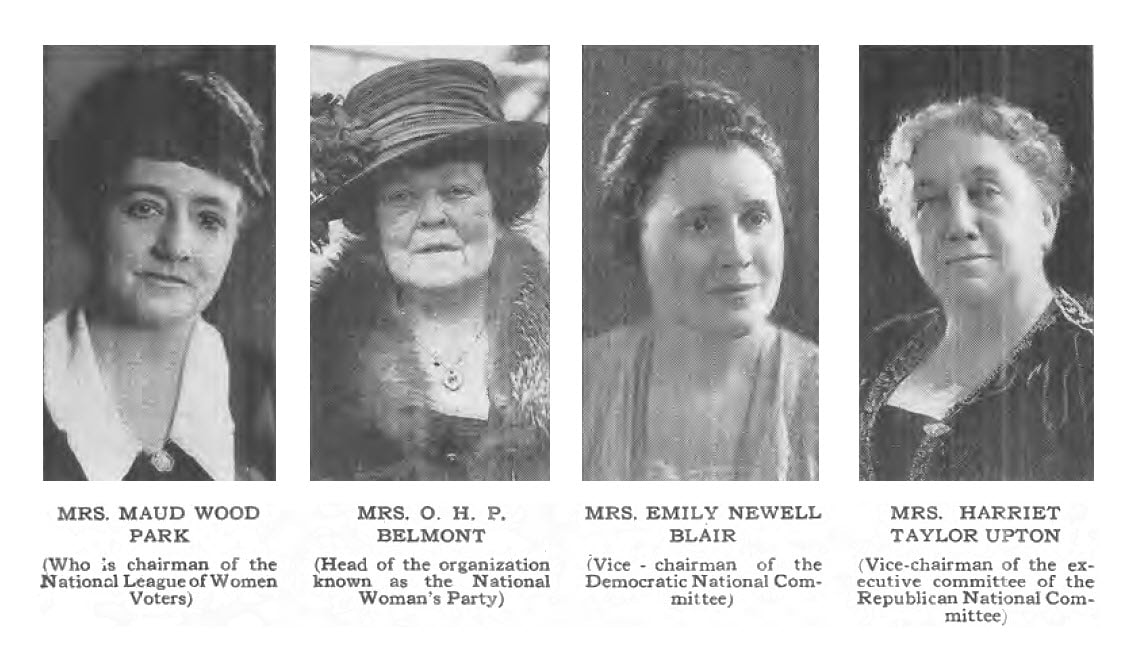

The pictures of these female political leaders was included as part of this article.