Ford Crushes Shareholder-First and -Foremost

|

|

Date Published: June 10, 2021

Date Modified: April 27, 2024 |

The list of the American industrialists who discouraged shareholder‑first and ‑foremost is quite formidable: Thomas J. Watson Sr. of IBM, George Eastman of Kodak, Owen D. Young of General Electric, Harvey S. Firestone of the Firestone Tire Company, and George F. Johnson of the Endicott-Johnson Corporation – to name a few. These industrialists verbalized their displeasure with shareholders who confused owning a business’ stock for which they were due a fair return, with business ownership which meant prioritizing and balancing investments from earnings to ensure a firm’s high performance and long-term survival.

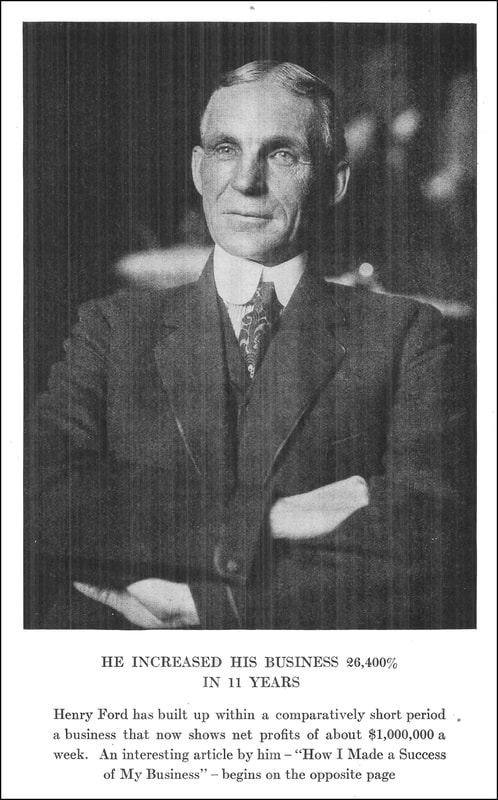

Even so, it is rare to find examples as outsized as Henry Ford’s reaction when he was challenged in court by his stockholders. Henry Ford, like many of his peers, practiced business-first.

Even so, it is rare to find examples as outsized as Henry Ford’s reaction when he was challenged in court by his stockholders. Henry Ford, like many of his peers, practiced business-first.

Henry Ford Crushes Shareholder-First and -Foremost

- Defining an Extreme of Maximizing Shareholder Value

- A Display of Chief Executive Autocracy

- The Ford Shareholders Strike the First Blow

- The Ford Motor Company Trial

- Henry Ford Delivers a Knockout Blow

- Great Executives Believe in Business-First

Defining an Extreme of Maximizing Shareholder Value

In 1956, THINK Magazine clearly defined four corporate stakeholders with the adage, “Business exists to provide a service to MAN — service to consumer man, to worker man, to investor man, and to the community of man.” Every individual, as they go through daily life, swaps out the mantles of different stakeholder personas. They are a consumer dropping off their children at a local day care; they are a worker assembling a new marketing campaign; they are an investor checking on their 401(k)/403(b) savings; and they are a member of a society that expects traffic signals — built by corporations and properly positioned by government entities — to keep them and their children safe on the communal roads home after work.

To achieve harmony within an economic society called a corporation, these stakeholders must coexist in a sustainable fashion as all individuals are – at times – customers, employees and shareholders; and all corporations are vested in the success or failure of their supportive societies. Individuals expect to be treated fairly in all aspects of their lives not just one. And yet there has always been an extreme philosophy of shareholder maximization that expects a razor-sharp focus on shareholder value even to the detriment of all the other stakeholders. This extreme philosophy of economic thought around maximizing shareholder value is better referred to as shareholder‑first and ‑foremost.

The list of the American industrialists who discouraged shareholder‑first and ‑foremost is quite formidable: Thomas J. Watson Sr. of IBM, Owen D. Young of General Electric, Harvey S. Firestone of the Firestone Tire Company, and George F. Johnson of the Endicott-Johnson Corporation – to name a few. These industrialists verbalized their displeasure with shareholders who confused owning a business’ stock for which they were due a fair return, with business ownership which meant prioritizing and balancing investments from earnings to ensure a firm’s high performance and long-term survival.

Even so, it is rare to find examples as outsized as Henry Ford’s reaction when he was challenged in court by his stockholders. Then again, Henry Ford did everything in a big way, and when his shareholders disagreed with his plans to expand the Ford Motor Company, he took them to school. We can add Henry Ford to an ever-lengthening list of early American industrialists who fought shareholder-first and -foremost.

Instead, Henry Ford, like many of his peers, practiced business-first.

To achieve harmony within an economic society called a corporation, these stakeholders must coexist in a sustainable fashion as all individuals are – at times – customers, employees and shareholders; and all corporations are vested in the success or failure of their supportive societies. Individuals expect to be treated fairly in all aspects of their lives not just one. And yet there has always been an extreme philosophy of shareholder maximization that expects a razor-sharp focus on shareholder value even to the detriment of all the other stakeholders. This extreme philosophy of economic thought around maximizing shareholder value is better referred to as shareholder‑first and ‑foremost.

The list of the American industrialists who discouraged shareholder‑first and ‑foremost is quite formidable: Thomas J. Watson Sr. of IBM, Owen D. Young of General Electric, Harvey S. Firestone of the Firestone Tire Company, and George F. Johnson of the Endicott-Johnson Corporation – to name a few. These industrialists verbalized their displeasure with shareholders who confused owning a business’ stock for which they were due a fair return, with business ownership which meant prioritizing and balancing investments from earnings to ensure a firm’s high performance and long-term survival.

Even so, it is rare to find examples as outsized as Henry Ford’s reaction when he was challenged in court by his stockholders. Then again, Henry Ford did everything in a big way, and when his shareholders disagreed with his plans to expand the Ford Motor Company, he took them to school. We can add Henry Ford to an ever-lengthening list of early American industrialists who fought shareholder-first and -foremost.

Instead, Henry Ford, like many of his peers, practiced business-first.

A Display of Chief Executive Autocracy

|

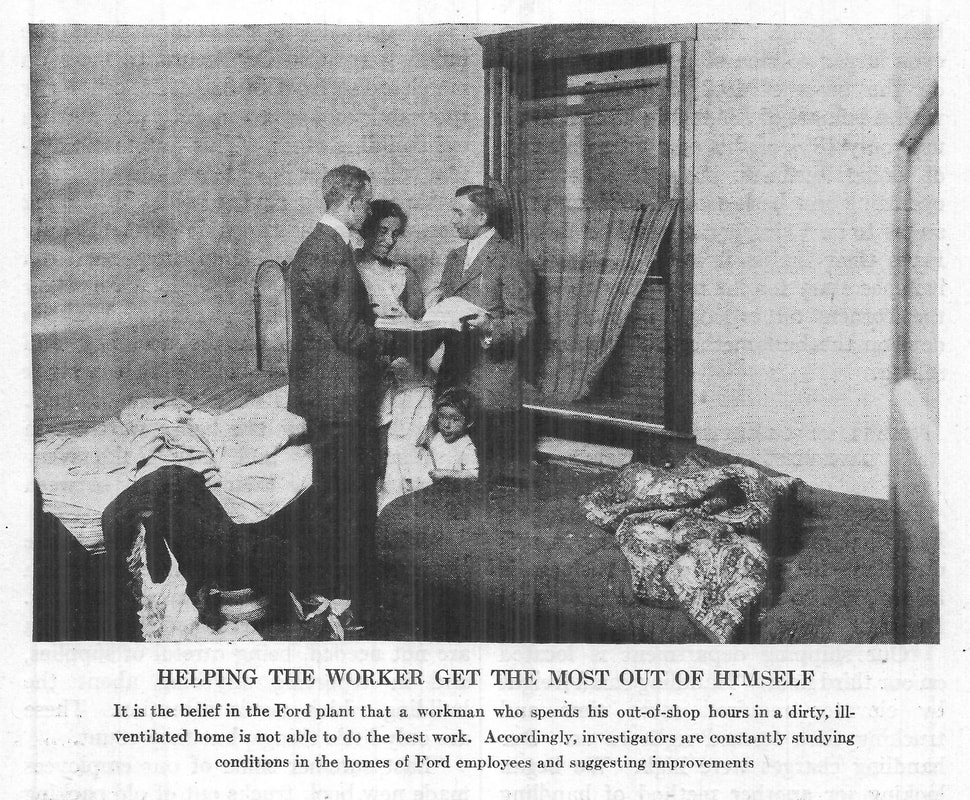

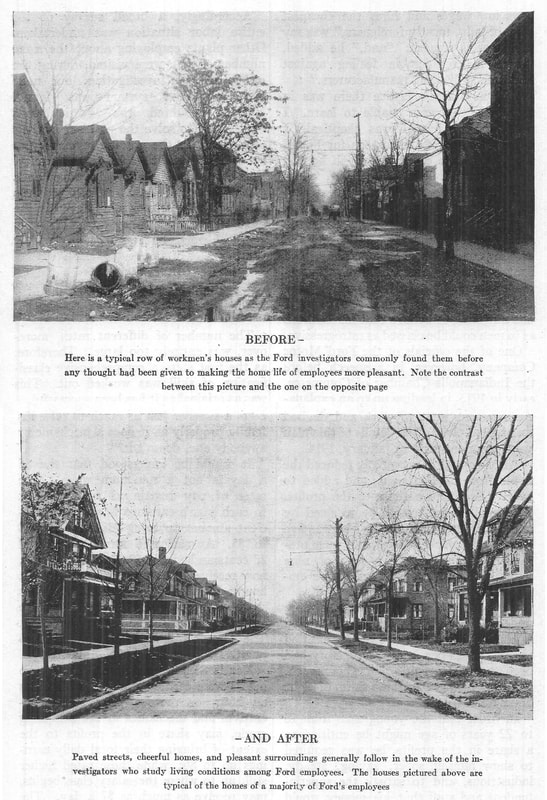

In 1938, the United States government enacted the first federal minimum wage of $2.00 for an eight-hour day. A quarter of a century earlier, Henry Ford initiated a corporate-wide minimum daily wage of $5.00 for an eight-hour day. Five years later he raised it to $6.00 a day, and ten years after that to $7.00 a day. The initial announcement in 1914 was a proclamation heard around the world by the consumers of Ford cars, trucks and tractors—the working man. A small retailer in Italy, when he discovered a newspaper man from Detroit shopping in his store, asked, “Does Henry Ford really pay the men that sweep his factories $6.00 and $7.00 a day?”

|

|

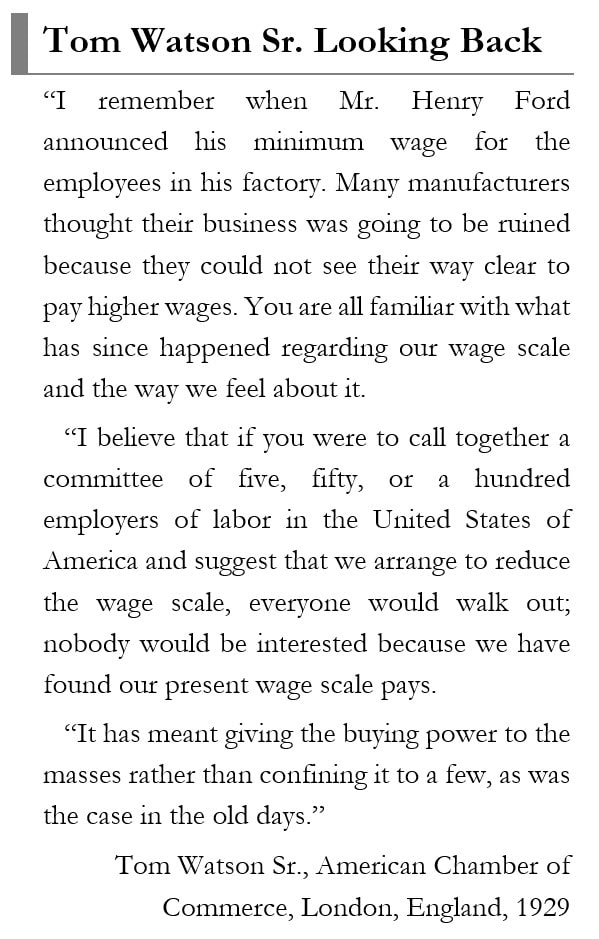

This didn’t mean, though, that the wage increases were without their controversy. The reactions to Henry Ford’s profit-sharing plan in 1914 were the extremes of fear and praise. [see the sidebar provided with Tom Watson Sr.'s perspective looking back on this decision almost fifteen years later.]

Some business men commented that they could agree with an eight-hour day, but not a five-dollar, eight-hour day; some cried “business philanthropy” but others observed it was “less philanthropy than a means of distancing [the Ford Motor Company from] all competitors;” some saw it as an “utopian project” but others saw it as a way to get the “pick of the labor market;” some believed it would be “the ruin of all business in this country,” while others thought it would boost demand for “automobiles, player pianos and all kinds of industrial products.” One competitor emotionally suggested that it was too “radical a step to take without talking to other automobile manufacturers,” while another observed pragmatically that one man “cannot change the policies of a whole industry.” |

Some labor unions said they had “no criticism to make,” but Samuel Gompers effused praise saying, “The new plan … will demonstrate its justice as well as its economy;” some observed it might lead to “labor unrest,” but John Mitchell said, “I cannot conceive of any evil effects from raising wages … I have no doubt that it will augment a feeling of discontent on the part of the workingman, but I do not think it will be an unintelligent discontent.” Prominent socialists declared their cause had “gained mightily” through this action, but some conservatives observed that a sudden increase in wages robs a man of his “ambition, does not improve his working capacity,” and leads to “extravagant methods of living.”

Some chief executives observed that they had “stockholders … to please” and that they would “never stand for it.” Some “refused to discuss the plan … [because] it is too serious of a matter to talk about,” but Andrew Carnegie told the press, “I congratulate Mr. Ford on making such a record … I presume the company is composed of stockholders … we must congratulate all of them … may others be moved to follow his example.” As Mr. Ford was closing one of his many interviews about the new policy Ford’s comment uncovers a fallacy in Mr. Carnegie’s presumption: “I made the announcement without consulting the other stockholders … If the other stockholders do not agree … I will pay the money promised out of my own share of the profits.”

This last statement was “presumably” a concern to his other shareholders because even if an individual agrees with a decision, there is always a desire to be asked and heard. This attitude of autocracy was one of the factors that set up Henry Ford for one of the battles of his life: Who would own and operate the Ford Motor Company.

Some chief executives observed that they had “stockholders … to please” and that they would “never stand for it.” Some “refused to discuss the plan … [because] it is too serious of a matter to talk about,” but Andrew Carnegie told the press, “I congratulate Mr. Ford on making such a record … I presume the company is composed of stockholders … we must congratulate all of them … may others be moved to follow his example.” As Mr. Ford was closing one of his many interviews about the new policy Ford’s comment uncovers a fallacy in Mr. Carnegie’s presumption: “I made the announcement without consulting the other stockholders … If the other stockholders do not agree … I will pay the money promised out of my own share of the profits.”

This last statement was “presumably” a concern to his other shareholders because even if an individual agrees with a decision, there is always a desire to be asked and heard. This attitude of autocracy was one of the factors that set up Henry Ford for one of the battles of his life: Who would own and operate the Ford Motor Company.

The Ford Shareholders Strike the First Blow

|

In 1916, Henry Ford announced one of the biggest investments he had ever considered. He was going to expand the Highland Park and River Rouge plants. It was a gargantuan gamble which, unknown to anyone at the time, would be made into the teeth of a major eighteen-month economic downturn: The Recession of 1920-21.

At the same time Ford Motor Company had just delivered one of its most profitable years in its history. On $207 million in sales the company made $60 million, and it had cash on hand and in banks totaling $53 million. Mr. Ford announced that while he intended to continue the regular dividend of 5 per cent a month on the capital stock of $2,000,000, he was going to stop the distribution of “lavish” special dividends—$41,000,000 from December 1911 to October 1915. Some of the shareholders were concerned. They were tired of seeing profits frittered away on price reductions and rebates for consumers, larger paychecks for workers, investments in an uncertain future, and cleaning up the workers’ communities outside the Ford plants. |

So, in November, the stockholders went to court to make sure they received what they believed was their fair share of the windfall. They filed suit to stop the plant expansions, to require the distribution of any future earnings as dividends—less only what was needed in reserves for emergencies, and because they didn’t trust Mr. Ford, they asked the court to appoint a receiver to ensure compliance.

The shareholders, though, were hardly suffering as an investment of $10,000 in 1903 had, in thirteen years, delivered $6.6 million in dividends and was at the time worth $35 million. This was a compounded annual growth rate of 89.8%.

It is a perfect example of shareholder-first and -foremost syndrome.

And the fight was at least partially triggered by Ford’s arrogance.

The shareholders, though, were hardly suffering as an investment of $10,000 in 1903 had, in thirteen years, delivered $6.6 million in dividends and was at the time worth $35 million. This was a compounded annual growth rate of 89.8%.

It is a perfect example of shareholder-first and -foremost syndrome.

And the fight was at least partially triggered by Ford’s arrogance.

The Ford Motor Company Trial

|

Henry Ford known for making outrageous and contradictory statements didn’t help himself much on the court room stand. He talked of his love of mankind and willingness to share the benefits of his industrial system with others.

William C. Richards in The Last Billionaire wrote. What Ford said at times was so opposed to accepted [business] thinking and practice that one never was quite sure if here was a man who dearly loved the grandiose and the startling, and who, after picking one long-shot, had become a confirmed bettor on outsiders. Either that or he was a genius with a spark so rare it escaped persons attuned to other wave lengths. To document the chief executive’s absurd wave length, the attorney for the shareholders shared this Ford quote from a press interview during the trial:

|

We easily could have maintained our prices for this year and again cleaned up $60,000,000 to $75,000,000 but I do not think it would be right to do so. We cut prices and are now clearing $2,000,000 to $2,500,000 a month, which is all any firm ought to make unless the money is to be used for expansion. I have been fighting to hold down income.

Much of what he said on the stand flowed against the popular belief of how a business should be run, and the judge ruled for the shareholders. He wrote that since the shareholders owned the company, Ford had to distribute $19 million as a special dividend. On appeal, the Michigan Supreme Court let the special dividend ruling stand because a corporation is organized “primarily for the profit of the stockholders.” Ironically, because Ford was the largest shareholder, $11 of the $19 million went to him.

More importantly, the Michigan Supreme Court did overrule the lower court and allowed the River Rouge expansion plans to move forward. It wrote that the corporation could use unemployed capital for expansion. But Ford was convinced it was time to teach his shareholders an object lesson: there is a difference between owning a business’ stock and practicing good business ownership.

So, he decided to take back control of his company.

More importantly, the Michigan Supreme Court did overrule the lower court and allowed the River Rouge expansion plans to move forward. It wrote that the corporation could use unemployed capital for expansion. But Ford was convinced it was time to teach his shareholders an object lesson: there is a difference between owning a business’ stock and practicing good business ownership.

So, he decided to take back control of his company.

Henry Delivers a Knockout Blow

Henry Ford announced both his and his son’s resignation from Ford Motor Company. The press wrote that this meant the “abandonment by the Fords of the direct management of the present company in Detroit.” The elder Ford announced further—with his usual flamboyant flair for an eagerly awaiting press—that he was going to launch a new automobile enterprise.

In fact, he said he was designing a new vehicle while he was in California on vacation. He told the press, it is “a better car than he is now building” and he would market it “at a lower price” through a company “other than Ford Motor Company.” And to ensure the story went “viral,” he captured the attention of the local press by telling them he was “contemplating” a factory in the Bay Area and a “great steel plant” in Los Angeles. The Industrial Committee of the Oakland Chamber of Commerce immediately went into action to bring the “contemplated” factory to their community. The story made headlines and front-page news around the world. One newspaper displayed on its front page: “$250 Flivver is Ford’s Promise.”

The next day paperboys delivered Henry Ford’s key message to his shareholders worldwide as they flipped the morning newspaper onto front lawns or sent the newsprint sailing with a bang against a front door. When the shareholders unfurled their local newspapers—possibly still in their bathrobes, they read the top story of the day with a clear message from Henry Ford: He was going to compete directly with what was now “their” company. The shareholders could keep their dividends - if they knew how to run a business better than him.

Mr. Richards wrote that the interviews “scared the wits out of some of the stockholders … because the Ford Motor Company without Ford was unthinkable and frightening.” Henry Ford’s press barrage provided the air cover he needed to stage a guardian-type, corporate coup d’état. Ford made offers and the shareholders sold their stock.

He was back in complete control, and shareholder-first and -foremost was dead for the time being at Ford Motor Company.

In fact, he said he was designing a new vehicle while he was in California on vacation. He told the press, it is “a better car than he is now building” and he would market it “at a lower price” through a company “other than Ford Motor Company.” And to ensure the story went “viral,” he captured the attention of the local press by telling them he was “contemplating” a factory in the Bay Area and a “great steel plant” in Los Angeles. The Industrial Committee of the Oakland Chamber of Commerce immediately went into action to bring the “contemplated” factory to their community. The story made headlines and front-page news around the world. One newspaper displayed on its front page: “$250 Flivver is Ford’s Promise.”

The next day paperboys delivered Henry Ford’s key message to his shareholders worldwide as they flipped the morning newspaper onto front lawns or sent the newsprint sailing with a bang against a front door. When the shareholders unfurled their local newspapers—possibly still in their bathrobes, they read the top story of the day with a clear message from Henry Ford: He was going to compete directly with what was now “their” company. The shareholders could keep their dividends - if they knew how to run a business better than him.

Mr. Richards wrote that the interviews “scared the wits out of some of the stockholders … because the Ford Motor Company without Ford was unthinkable and frightening.” Henry Ford’s press barrage provided the air cover he needed to stage a guardian-type, corporate coup d’état. Ford made offers and the shareholders sold their stock.

He was back in complete control, and shareholder-first and -foremost was dead for the time being at Ford Motor Company.

Great Executives Believe in Business-First

Any individual stakeholder who believes their standing as a consumer, worker, investor or member of any community entitles them to a special hyphenated consideration of -first and -foremost, would be at odds with not just Henry Ford but many of America’s greatest, twentieth-century industrialists. For this elite group, it was business-first, not shareholder-first and -foremost, not labor-first and -foremost, not society-first and -foremost, and especially not me-first and -only. These industrialists believed in business-first, and one of their top jobs was ensuring an equitable distribution of profits between stakeholders supported by a judicious communication plan explaining why to maintain a healthy and content stakeholder ecosystem.

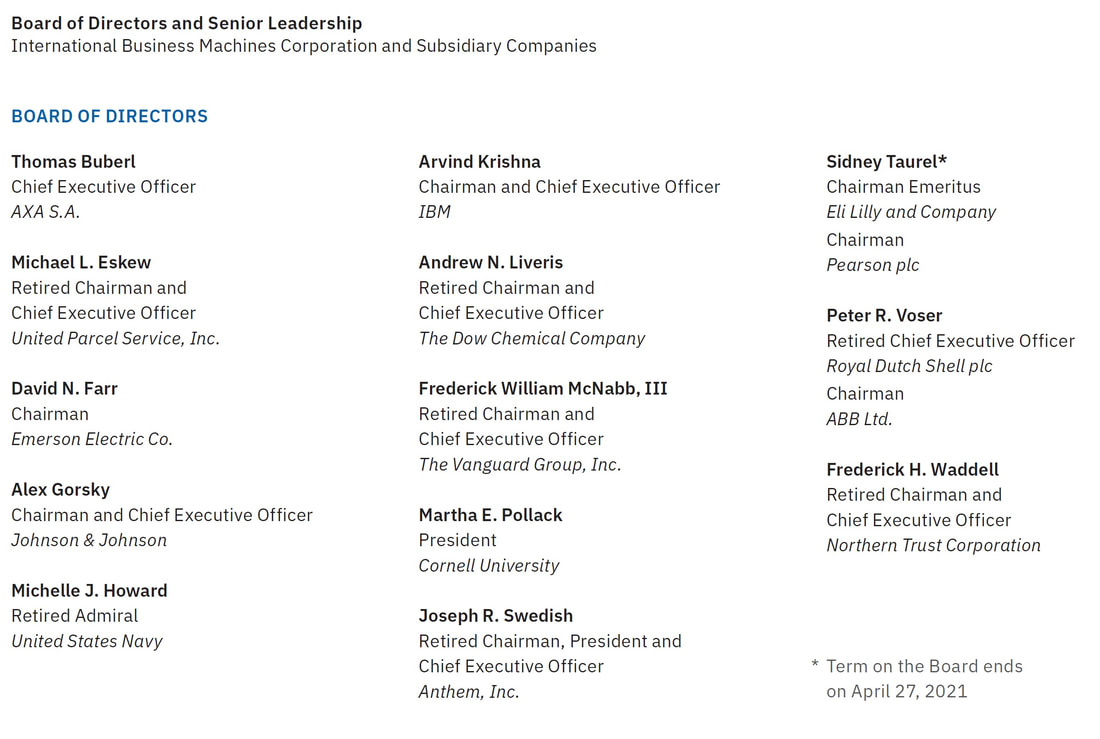

It was a strong stakeholder ecosystem, maintained by the chief executives, that carried IBM through its major economic, political and competitive tests of the 20th Century. But IBM's current stakeholder ecosystem is sick. IBM's 21st Century Chief Executives have failed the corporation by myopically spending $190,000,000,000 on its own paper: its stock. It is time for the board of directors to demand that IBM abandon this two-decade-long, failed strategy. The corporation must return to its proven business-first strategy that can restore it to greatness. IBM has recovered before and it can again … if the board acts. If the board fails to act …

… they will have failed a great company.

May the following men and women be remembered as those who either failed a great company or took action to restore a balance within a badly damaged stakeholder ecosystem of customers, employees, shareholders, and the economic, political and social societies they inhabit together.

It was a strong stakeholder ecosystem, maintained by the chief executives, that carried IBM through its major economic, political and competitive tests of the 20th Century. But IBM's current stakeholder ecosystem is sick. IBM's 21st Century Chief Executives have failed the corporation by myopically spending $190,000,000,000 on its own paper: its stock. It is time for the board of directors to demand that IBM abandon this two-decade-long, failed strategy. The corporation must return to its proven business-first strategy that can restore it to greatness. IBM has recovered before and it can again … if the board acts. If the board fails to act …

… they will have failed a great company.

May the following men and women be remembered as those who either failed a great company or took action to restore a balance within a badly damaged stakeholder ecosystem of customers, employees, shareholders, and the economic, political and social societies they inhabit together.