Introduction to "Ideas and High Ideals for the 21st Century"

|

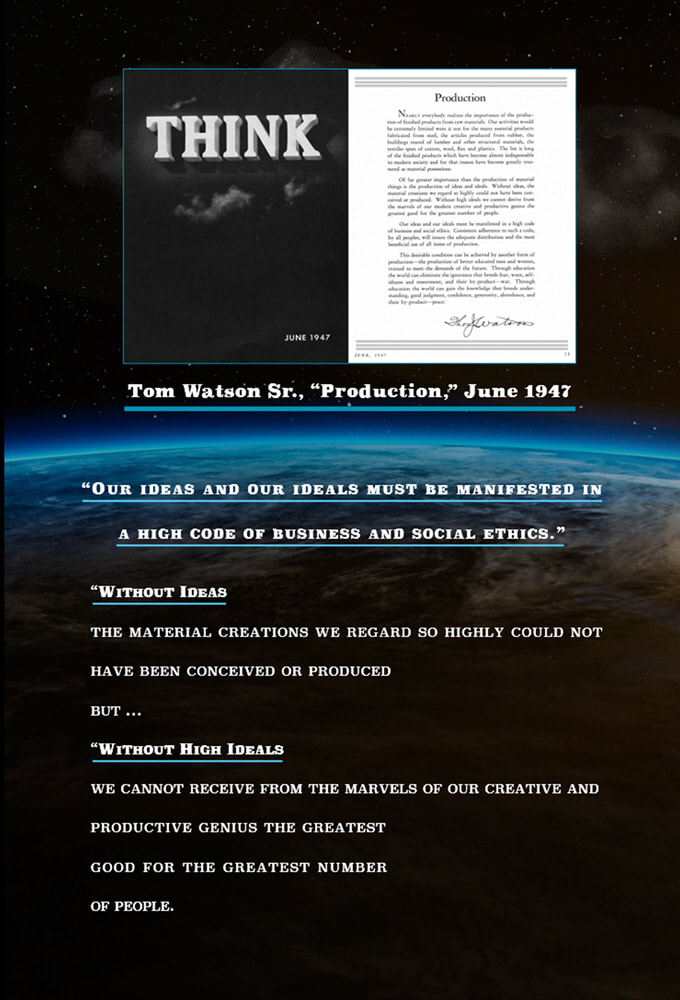

Once a month for twenty-one years, Tom Watson introduced each issue of THINK Magazine with his editorial thoughts. They were short and easily read; they were contemplative in nature; and they revealed his innermost feelings. Usually the title and the topic were identical and straightforward; and they were usually written on a singular theme such as “Service,” “Faith,” or “Fortitude,” or additionally, “Genius,” “Culture,” or “Purpose.” Sometimes, a more intriguing title pulled the reader in such as “The Voice Within,” “The Windows of Our Minds,” or “The Light of Inspiration.”

These editorials were written during times of inspiration and sometimes—as World War II loomed, desperation. They give the reader a formal glimpse into Watson’s drive and motivations. Reading his thoughts on so many divergent topics, is the first step in understanding Tom Watson as a complete human being—a way to reach beyond his well-documented record as a businessman. |

For two decades, his readership experienced his thoughts, dreams, and persuasive insights. Today’s reader, through these editorials, gains a preliminary insight into Tom Watson’s character by examining his ideas and the highest of his ideals—his thoughts, beliefs, and values. Any historian or biographer who wishes to capture, examine, understand, and interpret this chief executive officer’s motivations, should start with this collection. It is a dependable, long-term, grounding-stake from which to conduct further research. Tom Watson speaks for himself through this collection.

Reviewers of these editorials asked multiple questions. These were valid and important questions that should be—and are, answered in this Introduction:

Reviewers of these editorials asked multiple questions. These were valid and important questions that should be—and are, answered in this Introduction:

- “Did Tom Watson Write these Editorials?”

- “How Important Were these Editorials to Tom Watson?”

- “How did Tom Watson Acquire the Knowledge Displayed in these Editorials?”

- “Did these Editorials Make a Difference?”

Did Tom Watson Write These Editorials?

Yes, Tom Watson wrote these articles; he did not just “sign off” on them.

|

The strongest evidence that Tom Watson scribed these editorials and that they reflected his personality, is found in the most highly-cited, biography of his life: The Lengthening Shadow.

“In 1935, Watson carried this policy [of institutional advertising] one step further by publishing THINK. An experienced journalist was brought in to be its editor [Edmund F. Hackett], and leading men [and women] from many fields were contributors. Watson wrote the editorials, conscientiously, working them over himself. |

No, no one could make Watson be anything else—with the lone exception of his wife and soulmate of forty-two years. He said of her: “Mrs. Watson has always been my chief advisor and counsel in my business, spiritual, and international affairs.” At the time of her husband’s death, it was estimated that she had traveled at his side for “more than a million miles across the globe.” And of course, because of Tom Watson’s well-known aversion to air travel, this was accomplished via cars, trains, and ships.

They had plenty of time to talk.

They had plenty of time to talk.

How Important Were These Editorials to Tom Watson?

These editorials were important to Tom Watson; he studied and strained over their content.

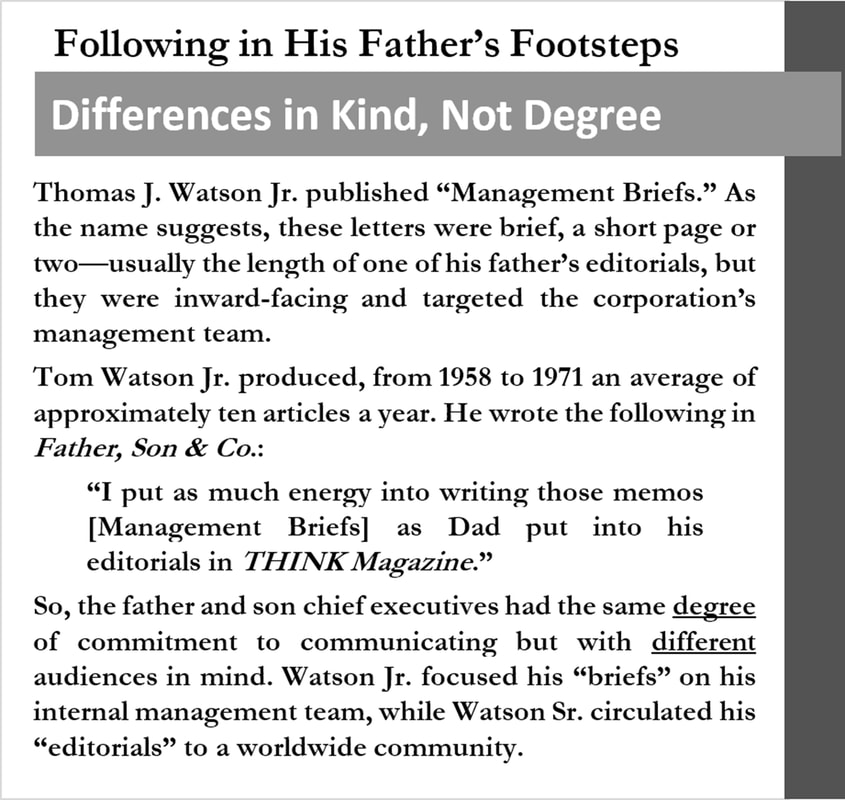

Thomas J. Watson Jr. wrote in the Memorial Issue of THINK Magazine dedicated to his father that he “took a very deep interest in the content of the publication, including the writing of an editorial worthy of the readership.” With a touch of sarcasm, the son provides further evidence in Father, Son & Company that his father was passionate about these editorials:

Thomas J. Watson Jr. wrote in the Memorial Issue of THINK Magazine dedicated to his father that he “took a very deep interest in the content of the publication, including the writing of an editorial worthy of the readership.” With a touch of sarcasm, the son provides further evidence in Father, Son & Company that his father was passionate about these editorials:

“Every issue opened with an editorial on world progress, written by Dad. … He would work on his editorials for THINK Magazine as though it were TIME, and he were Henry Luce and millions of people were waiting to hear what he had to say.” [emphasis added]

|

Sarcasm aside, it can be seen from the sidebar that Watson’s son put the same energy into his “Management Briefs.” The differences between father and son were in kind—target audience and scope, not in degree—investment of time and energy. They both invested heavily in appealing to their unique audiences.

Within this context, also consider the following. Tom Watson wrote these lead-in articles to his corporate magazine every month for twenty-one years: from his first editorial entitled “Introducing ‘THINK’ ” at the age of 61 in June 1935, to his last editorial entitled “Youth” published upon his death at the age of 82 in June 1956—253 monthly editorials without an omission and only one reprint at the readers’ request: “Justice vs. Revenge.” |

He wrote these editorials as he and his corporation wrestled with the second downturn of the Great Depression, fought four ensuing recessions, and met the needs of war-time democracies during two wars: World War II and the Korean War.

|

An example of a THINK Magazine luminary edition in honor of Dr. Edvard Benes, President of Czechoslovakia.

|

Beyond the monthly editorials contained in this book, he also wrote additional editorials for THINK Magazine’s luminary editions that focused on historic figures such as Dwight D. Eisenhower as a “Symbol of America,” Mme. Chiang Kai-shek as the “First Lady of China,” and Dr. Edvard Benes as the “President of Czechoslovakia.”

His editorials also introduced THINK Magazine’s special editions that covered topics such as the “National Automotive Golden Jubilee,” “Diary of U. S. Participation in World War II,” “Contemporary Art of 79 Countries,” and “Contemporary Art of the Western Hemisphere.” Through all these years, he met print deadlines as he traveled worldwide visiting his employees at laboratories and sales branch offices. When Europe was at peace, he met print deadlines as the corporation’s “first couple” journeyed to, sojourned within, and returned from Europe—multiple times they were out of country for six months at a time. When Europe was at war, he met print deadlines as they visited Canada, Mexico, Central and South America. And, of course, during their “down time” in the United States they made seemingly weekly excursions to the Endicott and Poughkeepsie plants, and visited the sales branch offices across the country. |

He met these press deadlines while carrying not only the executive responsibilities as President and Chairman of the Board of IBM, but, at times, President of the International Chamber of Commerce; Trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Trustee of Lafayette, Columbia, and New York Universities; and as a director, trustee, or national sponsor of innumerable war-relief organizations such as the Commission for Polish Relief, the United Yugoslavia Relief Fund, the Greek War Relief Association, and the American-Korean Foundation, and as a director, trustee, or national sponsor of countless humanitarian causes and youth organizations such as the Salvation Army, the YMCA, the YWCA, the International Boy Scouts, and the Save the Children Federation—to name only a few.

Obviously, these editorials were of great importance to Tom Watson. He prioritized their writing, and they are worthy of publication and study; but how did he access the knowledge embodied in these articles?

Obviously, these editorials were of great importance to Tom Watson. He prioritized their writing, and they are worthy of publication and study; but how did he access the knowledge embodied in these articles?

How Did Tom Watson Acquire the Knowledge Displayed in these Editorials?

|

Although Tom Watson never attended college, he was fully capable of writing these editorials; he practiced a lifetime of self-education. He lived his life as he encouraged others to live theirs: ensuring there was “no saturation point” in the pursuit of one’s own self-education.

The scope of his studies—his “bookishness” as described in the sidebar, included the philosophies of individuals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. He examined the works of pioneers in science such as Orville Wright, and forerunners in human relations such as Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson. He highlighted the inventive practices of such individuals as Leonardo Da Vinci, Galileo, Paracelsus, and Henry Bessemer. Additionally, he encouraged and provided opportunities for others to read. |

Tom Watson supplemented his reading by joining, attending, and leading an amazing number of business and social clubs. One of the purposes of these associations was to exchange actionable information between peers: The Sphinx Club of New York (evolving into the Advertising Club of New York) was a gentlemen’s club for dining, sharing ideas on advertising, and hearing prominent speakers of the day; The Economic Club of New York was a non-profit, nonpartisan, nonpolitical organization dedicated to the discussion of important social, economic, and political questions; The Sales Executives Club of New York attempted to raise the practices and prestige of the sales profession by pioneering changes in the techniques and philosophy of selling. In these clubs, Tom Watson was a member, director, and vice-president or president of the first two clubs, and a founding member of the last. There were many other societies.

|

The individuals who attended or spoke at these meetings provided insights into the social, economic, and political issues of the day, and they were attended by some of the best and brightest business executives and political leaders that the world had to offer.

In addition to reading and interacting with his local and national peers in these business and social clubs, Watson’s life was full of interactions with an eclectic assortment of internationally prominent professionals from a wide range of professions. He hosted, moderated, and attended hundreds—quite easily thousands, of formal and informal events for internationally-renowned individuals. This maintained a flood of ideas that came from all walks of life and from everywhere, worldwide. Many of these individuals wrote articles for THINK Magazine, and their insights influenced Watson’s short editorials, his more in-depth articles, and his speeches. |

|

So, his depth of knowledge and insights in these editorials came not only from his personal studies and interactions with his local peers but innumerable, intimate interactions with internationally well-known, highly-respected individuals across a multitude of professions: capitalists, clergy, economists, industrialists, philosophers, politicians, explorers, ambassadors, statesmen, prime ministers, princesses and princes, queens and kings.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd President of the United States, remarked that in the handling of foreign dignitaries, “I take care of them in Washington. I have learned to rely confidently on Tom Watson to take care of them in New York.” At the time, Washington may have been the political capital of the United States but the country’s—and arguably the world’s, economic center was New York City; and Tom Watson was on-point, front-and-center for decades during this thriving metropolis’ prime. These international representatives constantly provided new, current, and ever-expanded insights on all levels into world affairs.

|

So Tom Watson practiced a life-time of self-education, groomed and maintained local, national, and international relationships across a myriad of eclectic professions to document his insights in over two decades of editorial thoughts; but did these editorials make a difference?

Did These Editorials Make a Difference?

People read, reacted to, and interacted over these editorials and his more in-depth articles. Sometimes, newspapers across the country reprinted them in their entirety.

The following are a few examples:

Tom Watson’s insights and quotes were also imbedded in syndicated columns and editorial sections as editors, journalists, and columnists cited his thoughts. The old man’s editorials were read and thoughtfully engaged. They accomplished their purpose: they stirred thought-provoking discussions; but was Tom Watson a Henry Luce?

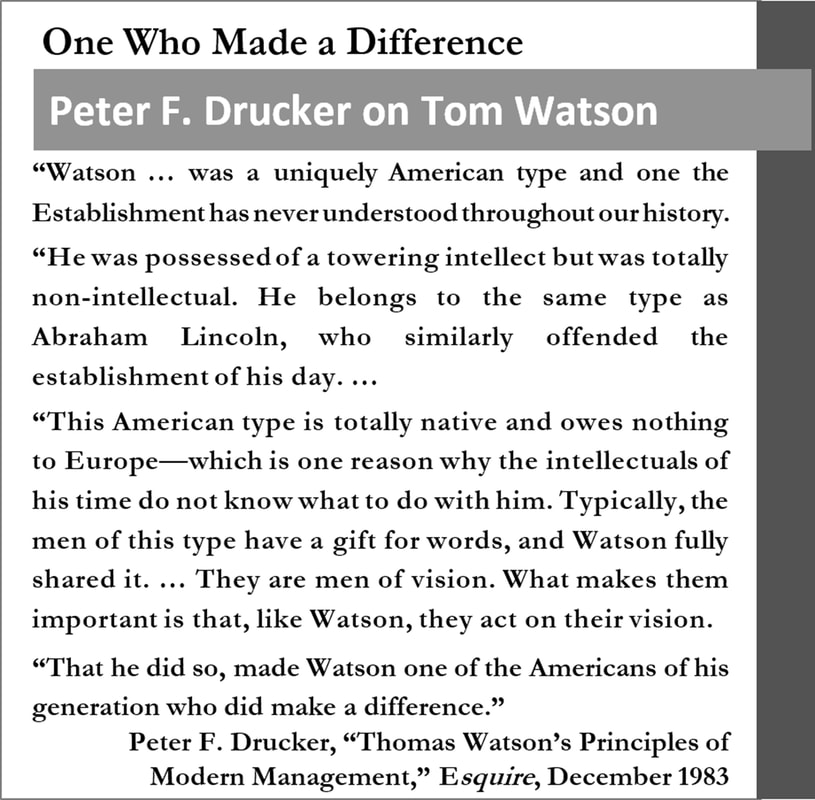

No, Watson was a businessman who published a magazine, not a publisher who ran a magazine business; but few in either profession have worked harder at making a difference in the world. He leveraged his economic and educational, military and political, humanitarian and philanthropic connections to make a difference.

The following are a few examples:

- On June 29, 1941, The Pensacola News-Journal reprinted the editorial “Service” from THINK Magazine’s May issue as the nation called its youth forward in preparation for war.

- On June 24, 1942, The Fort Worth Star-Telegram ran the editorial “Time” from THINK Magazine’s April issue.

- On February 18, 1943, The Nebraska-Journal Leader republished the editorial “The Glory of Democracy” from THINK Magazine’s October 1942 issue.

Tom Watson’s insights and quotes were also imbedded in syndicated columns and editorial sections as editors, journalists, and columnists cited his thoughts. The old man’s editorials were read and thoughtfully engaged. They accomplished their purpose: they stirred thought-provoking discussions; but was Tom Watson a Henry Luce?

No, Watson was a businessman who published a magazine, not a publisher who ran a magazine business; but few in either profession have worked harder at making a difference in the world. He leveraged his economic and educational, military and political, humanitarian and philanthropic connections to make a difference.

|

Here are a few more examples of how this businessman’s editorials made a difference.

In 1937–38, as the head of the International Chamber of Commerce, Tom Watson proposed a pathway to international peace built on a stable, equitable, economic coexistence between nations called “World Peace through World Trade.” He published “The Cost of War” to support his cause. It highlighted in graphic, factual detail the terrible costs of World War I—The Great War. It was “distributed in pamphlet form to peace enthusiasts, members of Congress, and Washington officials.” It touched the hearts of many members of Congress as it was read—in its entirety—into the Congressional Record. The article and subsets of its well-formed facts appeared in the press throughout the country for years. |

Tom Watson was doing his utmost to accomplish something most worthwhile: world peace. But it was an effort doomed from the start because of the aggression of dictators of his day. Too many have mistaken his positive nature for cluelessness or naïveté. Yet, his doubts and his positive nature are simultaneously represented in the editorial immediately preceding “The Cost of War.”

The editorial is entitled “Reward.”

The editorial is entitled “Reward.”

“Questions which confront every one of us from time to time are: ‘What am I getting out of life? What is my reward for all this effort? What is the sense of striving so hard?’ When we ask ourselves such questions, we are apt to be doing our utmost to accomplish something worthwhile, to forge ahead, to exemplify principles which form a fine human pattern … despite obstacles so unbelievable that they seem to have arisen just to thwart us—conditions that appear intolerable.

“At such times, our finest efforts seem destined for failure; and the more conscientious we are the deeper our discouragement is apt to be. Yet to feel discouraged at such a period is to lose heart when we should feel most hopeful—to be victims of our own lack of understanding.”

After the war started, Tom Watson—the most conscientious of men—must have felt the deepest of discouragements. As he writes above, his inner voice surely asked, “What is the sense of striving so hard?” And as the wars raged on in Europe, Africa, and Asia, he wrote a magnificent editorial about his feelings concerning the war’s death and destruction. In Atlanta, Georgia, as a small group of individuals met, one of the attendees rose in their midst to read this editorial on “Sharing.”

“Next to love, a common sorrow is the greatest bond between human souls.

“Today a common sorrow is being shared by every right-thinking person throughout the entire world because of the devastation which is being wrought by wars in Europe, Africa and Asia.

“Let all those whose thoughts are drawn together by this common sorrow, pause and do some balanced and constructive thinking, and as individuals, do their utmost toward planning a better world for the people of all nations when hostilities cease.”

I am sure that those in attendance in Atlanta and those who read the press account of the meeting murmured “Amen” to this shared hope for a better world to come. But the following month, the United States called its youth forward in preparation for war.

Watson’s editorial on “Service” resurfaced in the press.

Watson’s editorial on “Service” resurfaced in the press.

“As life unfolds to the youth of any nation, one of the greatest opportunities it presents is to be found in service. Service is its own reward. … That which constitutes true happiness … is inextricably involved in our willingness to serve.

“Because character … is inseparable from this spirit of service, no one attribute of humankind is more universally regarded as worthy of general recognition and wide acclaim. … We should think of our opportunity to be of service to all these young men who, at considerable personal sacrifice, have enrolled in the Army and Navy and are preparing to serve and protect us.”

At the time, Tom Watson was 67 years of age. His form of service could not be in uniform, but his two sons did enter the military service. Tom Watson focused his and his corporation’s efforts on democracy’s defense, and—following his own advice in the editorial, he supported the servicemen and -women in uniform.

|

Reading these editorials, you too may come to believe—as his son did, that they led off a magazine that was:

“The shadow and measure of my father’s character and personality. … He stood for the very finest things, had a deep religious belief, and approached each one of life’s problems from an optimistic and affirmative point of view.” Thomas J. Watson Jr., THINK Magazine, September 1956

Would that all sons and daughters could write as much of their fathers.

Tom Watson’s optimistic and affirmative point of view comes across in these editorials. They made a difference then, and they can again with a new generation. Which brings us to the purpose of this book. |

The Purpose of this Work: Hold Up a Light for all to See

|

“Truth, when not sought after, rarely comes to light.”

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes

Supreme Court Justice Holmes is often credited with this quote. It carries a serious tone—the tone of a jurist. The justice suggests that truth must be pursued: to bring truth into the light requires dedication, effort, and research. But this quote is only original through adaptation. The justice changed a single word in an adage scribed two thousand years prior:

“Truth, when not sought after, sometimes comes to light.”

Menander

|

Oliver Wendell Holmes

|

As opposed to the serious tone of a jurist, Menander—a dramatist and poet, used a writer’s dramatic sleight of hand to expose unforeseen truths. Clues may have been left everywhere—as in a great mystery, but suddenly, the pieces come together and the unsought truth reveals itself. It is a climax that catches the individual unaware. A method such as this, if handled properly, changes the opinions, the beliefs, and most importantly, the thinking of an observer.

In this work, I am experiencing the insights of both Holmes and Menander—a jurist and dramatist.

In the case of Holmes’ audience, how do I, an individual who has been researching and uncovering facts about Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM, create a desire in others to seek a similar enlightenment—truth seems too strong a word.

In the case of Menander’s audience, how do I expose unsought “enlightenments” in such a way that I eventually surprise an individual who isn’t seeking this particular knowledge and cause them to ponder—almost in disbelief, that “I think I have been enlightened.” It is the most daunting of tasks to reach the two different audiences of Holmes and Menander: the seeker and non-seeker alike.

In this work, I am experiencing the insights of both Holmes and Menander—a jurist and dramatist.

In the case of Holmes’ audience, how do I, an individual who has been researching and uncovering facts about Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM, create a desire in others to seek a similar enlightenment—truth seems too strong a word.

In the case of Menander’s audience, how do I expose unsought “enlightenments” in such a way that I eventually surprise an individual who isn’t seeking this particular knowledge and cause them to ponder—almost in disbelief, that “I think I have been enlightened.” It is the most daunting of tasks to reach the two different audiences of Holmes and Menander: the seeker and non-seeker alike.

|

But herein lies the purpose of this work: to bring to old, new, and future generations alike an enlightenment concerning one of America’s greatest industrialists—one of many, who helped lay the economic foundations upon which our capitalistic system could grow fairly and equitably in peace.

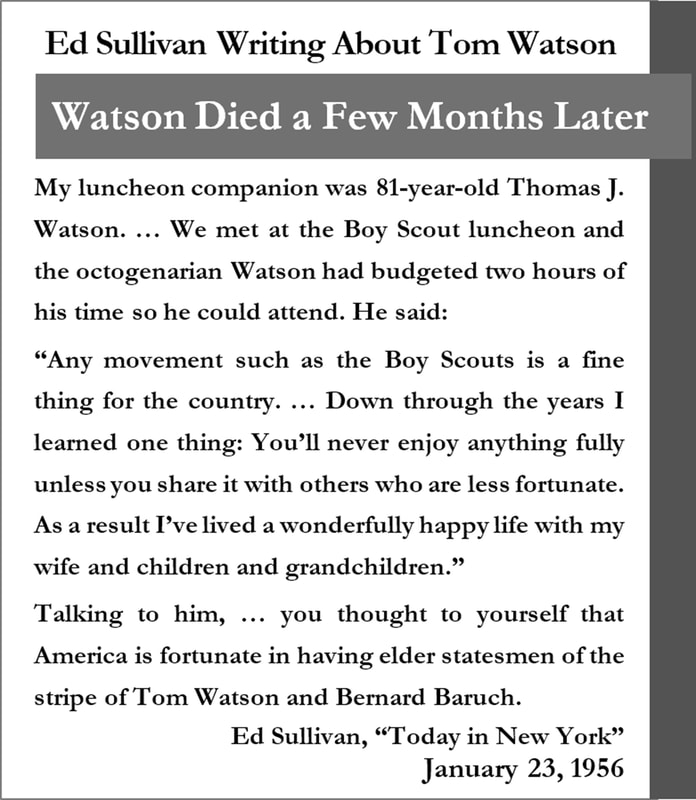

If this work has been done properly, it will make enlightenment easier for those who seek; and for those who don’t, it might occasionally surprise a non-seeker that there was an extremely successful, eighty-two-year-old businessman who spent his life working for a fair and equitable worldwide society. Maybe seeker and non-seeker alike will arrive at the same enlightenment that Ed Sullivan experienced when he wrote into his column after visiting with Thomas J. Watson Sr. at a Boy Scout luncheon that “America is fortunate in having elder statesmen of the stripe of Tom Watson.” |

Tom Watson: An American Industrialist with High Ideals

This work focuses on Tom Watson’s THINK Magazine editorials. At the same time, he was publishing end-of-year economic outlooks for press releases; he was speaking at innumerable baccalaureate exercises; he was composing full-length articles on topics of current interest to his readers. Wherever he went, whenever he spoke, whatever he wrote, he always shared his ideals openly—he wore his heart along with his ideals on his shirtsleeves.

During all these years, Tom Watson was a man who strove for international peace … and he pushed hard. When his finest efforts were thwarted by dictators who desired war, his discouragement showed through—one time. But, as always, he fell back on his faith, recovered his heart and hope, and strove forward believing that “the steps of faith may fall on a seeming void but they find the rock beneath.”

These editorials capture what Tom Watson believed, and there is an amazing consistency in the ideals he evangelized for more than two decades—as in equality of race and religion. Through these editorials, Tom Watson presented his personality, beliefs, and philosophies in an open record that spanned decades. As consolidated and presented here, this becomes one of the simplest, broadest, most authentic, and now, the most available record of a twentieth-century, American industrialist’s beliefs and values.

Those who teach business history should start with this man’s words as only one example of one of our great twentieth-century American industrialists because Tom Watson was never alone in these pursuits—he was one of many. Tom Watson typified the high ideals held by many of the industrialists of his generation and of those of a previous generation upon whose shoulders he and his peers stood.

These are the ideals that have proven quite historically persistent in our good businessmen and -women. The deeds of too many great industrialists are now lost in the demential fog of mankind’s long-term memory.

During all these years, Tom Watson was a man who strove for international peace … and he pushed hard. When his finest efforts were thwarted by dictators who desired war, his discouragement showed through—one time. But, as always, he fell back on his faith, recovered his heart and hope, and strove forward believing that “the steps of faith may fall on a seeming void but they find the rock beneath.”

These editorials capture what Tom Watson believed, and there is an amazing consistency in the ideals he evangelized for more than two decades—as in equality of race and religion. Through these editorials, Tom Watson presented his personality, beliefs, and philosophies in an open record that spanned decades. As consolidated and presented here, this becomes one of the simplest, broadest, most authentic, and now, the most available record of a twentieth-century, American industrialist’s beliefs and values.

Those who teach business history should start with this man’s words as only one example of one of our great twentieth-century American industrialists because Tom Watson was never alone in these pursuits—he was one of many. Tom Watson typified the high ideals held by many of the industrialists of his generation and of those of a previous generation upon whose shoulders he and his peers stood.

These are the ideals that have proven quite historically persistent in our good businessmen and -women. The deeds of too many great industrialists are now lost in the demential fog of mankind’s long-term memory.

|

May this collection of ideals reach the educated, the powerful, and the influential—at least those who temper their power and influence with an open mind and a peaceful heart, just as these editorials did when they were originally written.

This anthology starts with the THINK Magazine editorial that Tom Watson’s son wrote after his father’s death in 1956. This introduction ends with a reference to the one fundamental rule—the one singular belief, of Tom Watson that underpins these editorials, that flowed through his thinking and actions, and that motivated his lifetime of service. To Tom Watson, the “first rule” of admirable human behavior upon which to base all human relations was “The Golden Rule.” “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.” Cheers, - Peter |

“When men speak ill of thee, live so as nobody may believe them”

Plato

|