A Review of Ray Stannard Baker's "Following the Color Line"

|

|

Date Published: July 4, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

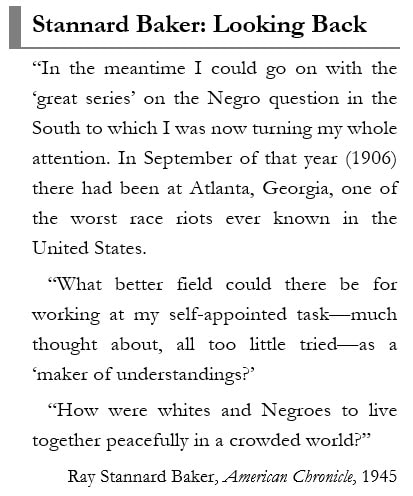

The information in this book was accumulated as Ray Stannard Baker covered more than 20,000 miles over three years (1906–08) in both the North and South studying the race issue in America. As with all fine works, this is a book that is as applicable today as it was over a century ago. If these ideas are received humbly, they will challenge both the overly-fanatical, compassionate soul and the overly-zealous, self-righteous wit. It helped me understand the weakness of thought in “separate but equal.” It is in our own best interests that we live in harmony with each other: equal and together.

Ray Stannard Baker wrote: “The race problem is the problem of living with human beings who are not like us, whether they are, in our estimation, our ‘superiors’ or ‘inferiors,’ whether they have kinky hair or pigtails, whether they are slant-eyed, hook-nosed, or thick lipped. In its essence it is the same problem, magnified, which besets every neighborhood, even every family.”

Since "Following the Color Line" starts with Atlanta’s Race Riot of 1906, let’s start our “Reviews of the Day” with the review of the book from The Atlanta Constitution.

You might be surprised.

Ray Stannard Baker wrote: “The race problem is the problem of living with human beings who are not like us, whether they are, in our estimation, our ‘superiors’ or ‘inferiors,’ whether they have kinky hair or pigtails, whether they are slant-eyed, hook-nosed, or thick lipped. In its essence it is the same problem, magnified, which besets every neighborhood, even every family.”

Since "Following the Color Line" starts with Atlanta’s Race Riot of 1906, let’s start our “Reviews of the Day” with the review of the book from The Atlanta Constitution.

You might be surprised.

Peter E. Greulich

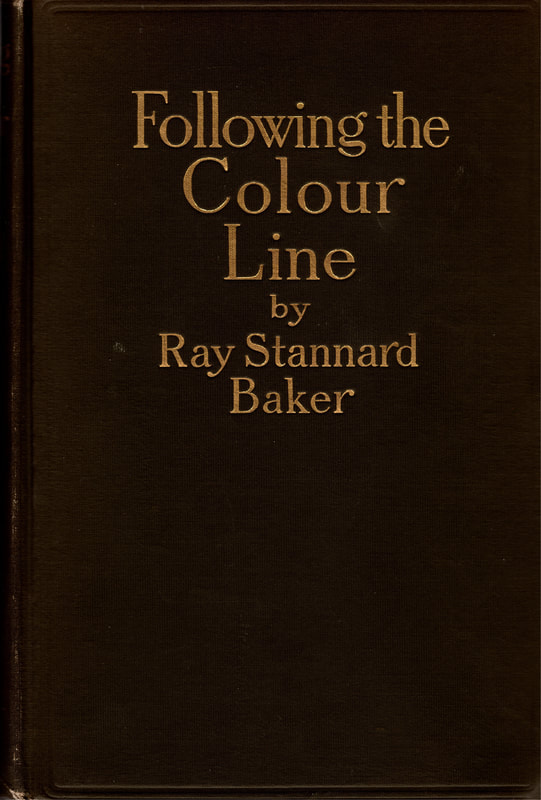

A Review of Ray Stannard Baker's: "Following the Color Line"

- North, South, West, and Black “Reviews of the Day:” 1908–09

- Insights from "Following the Color Line"

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

North, South, West, and Black “Reviews of the Day:” 1908–09

|

“Barring the occasional tendency to generalize from exceptional premises or to elaborate single instances for the sake of a striking effect, Mr. Baker is to be cordially congratulated on what is an intelligent and sympathetic study of the race problem in the United States. … He does not mince language [about the Atlanta riot]. He sets forth the actual happenings of that ugly, brooding nightmare of two years ago in colors that do not screen its abhorrent aspect, while they do not disguise the unspeakable crimes that furnished the provocation. …

“The unsparing candor of Mr. Baker in discussing interracial conditions in the north entitles him to a respectful hearing in his testimony bearing on our own section [the south]. … It is in his final summary, after analyzing conditions north and south, that Mr. Baker is happiest and most convincing … the solution of this devious problem are ‘time’ and ‘patience.’ “He has no economic or socialistic nostrums or daydreams to advance … with negligible exceptions he is just and perceptive in gauging the attitude and the difficulties of the southern people.” Samuel W. Dibble, Literary, The Atlanta Constitution, 1908

|

“This book is a treatise on negro citizenship in the American democracy and its purpose is to make a clear statement of the exact conditions and relationships of the negro in American life. The author has endeavored to see every problem, not as a northerner or a southerner, but as an American.

“He does not look upon the negro as a menial in the south, nor as a curiosity in the north, but as a plain human being, animated with his own hopes, depressed by his own fears, and meeting his own problems.”

“He does not look upon the negro as a menial in the south, nor as a curiosity in the north, but as a plain human being, animated with his own hopes, depressed by his own fears, and meeting his own problems.”

New Books, The Joliet Illinois Herald, 1909

Editor's note: I especially like the following review because I consider “generalizations” the boundary markers of a lazy mind, a tool of the exploiters of human emotion, or, in an intelligent, curious mind, a “blind spot” that, as I get older, I find we all have—which must be dealt with constantly—because we don’t think hard enough in all aspects of our lives. Thoughts, beliefs and values should be in constant evolution not only between generations but within a single generation. I have told my friends and written previously that “The only generalization that any good, sane, intelligent man should consider repeating, is that ‘All generalizations are false.’ So, Research, Observe, Think and Act!”

“The errors that may be committed by the adoption of a generalization are brought to the front. … Mr. Baker heard the generalized statement … that there were localities in the South where negroes, having lost the restraint of white men, were rapidly returning to barbarism. …

“He visited the worst places. … He looked diligently and never found any such communities. … [Stannard wrote] ‘I found everywhere human beings struggling, failing, succeeding, fearing, hoping, like you and me—often densely ignorant and backward, sometimes cruelly exploited, sometimes helped by white employers, but no more hopeless than any other downtrodden uneducated classes of people. …

"When I went into the Yazoo delta in Mississippi expecting to find the worst, I found an example of the very best: a town called Mound Bayou which is owned and conducted exclusively by negroes with a negro mayor, a negro bank, negro stores, a negro cotton gin, and a negro station agent: a good town and not a white man in it!’”

“The errors that may be committed by the adoption of a generalization are brought to the front. … Mr. Baker heard the generalized statement … that there were localities in the South where negroes, having lost the restraint of white men, were rapidly returning to barbarism. …

“He visited the worst places. … He looked diligently and never found any such communities. … [Stannard wrote] ‘I found everywhere human beings struggling, failing, succeeding, fearing, hoping, like you and me—often densely ignorant and backward, sometimes cruelly exploited, sometimes helped by white employers, but no more hopeless than any other downtrodden uneducated classes of people. …

"When I went into the Yazoo delta in Mississippi expecting to find the worst, I found an example of the very best: a town called Mound Bayou which is owned and conducted exclusively by negroes with a negro mayor, a negro bank, negro stores, a negro cotton gin, and a negro station agent: a good town and not a white man in it!’”

Contemporary Literature, The Los Angeles Sunday Times II, 1908

Editor's note: Ray Stannard Baker wrote the following of one black-operated newspaper in the north, “The large proportion of colored newspapers in the country are supporters of [Booker T.] Washington and his ideals … the strongest and ablest of which is perhaps the New York Age [sentence was reordered for clarity].”

So, I was interested in what these editors thought of Stannard’s work. I was unable to find a review, but since this book is a consolidation of all “The Color Line” articles Stannard wrote for the American, here is what the editors wrote about one of his articles.

“With the prescience of inspiration Mr. Baker has thought out the main thing which operates to provoke perpetual hell in the Southern situation, when he writes:

“ ‘Many Southerners look back wistfully to the faithful, simple, ignorant, obedient, cheerful old plantation darkey, and deplore his disappearance. They want the New South, but the old darkey. The darkey is disappearing forever along with the old feudalism and the old-time exclusively agricultural life.’ …

“There is the whole race question in a nutshell.”

So, I was interested in what these editors thought of Stannard’s work. I was unable to find a review, but since this book is a consolidation of all “The Color Line” articles Stannard wrote for the American, here is what the editors wrote about one of his articles.

“With the prescience of inspiration Mr. Baker has thought out the main thing which operates to provoke perpetual hell in the Southern situation, when he writes:

“ ‘Many Southerners look back wistfully to the faithful, simple, ignorant, obedient, cheerful old plantation darkey, and deplore his disappearance. They want the New South, but the old darkey. The darkey is disappearing forever along with the old feudalism and the old-time exclusively agricultural life.’ …

“There is the whole race question in a nutshell.”

The New York Age, “Following the Color Line,” 1907

Insights from "Following the Color Line"

In the very first paragraph of the preface, Ray Stannard Baker states its purpose.

|

“My purpose in writing this book has been to make a clear statement of the exact present conditions and relationships of the Negro in American life. I am not vain enough to imagine that I have seen all the truth, nor that I have always placed the proper emphasis upon the facts that I here present. Every investigator necessarily has his personal equation or point of view. The best he can do is to set down the truth as he sees it, without bating a jot or adding a tittle, and this I have done..”

The following are some observations that I appreciated:

“What the investigator overhears is often of greater significance than what he hears.” “For democracy is like this: once its ferment begins to work in a nation it does not stop until it reaches and animates the uttermost man. ... Movements are so much greater than men, often going so much further than men intend. A prophet who stands out for truth ... cannot, having uttered it, thereafter, limit it nor recall it.”

|

Baker around 1914

|

“Personal relationships—the solving touch of human nature—play havoc with political theories and generalities. Mankind develops not by rules but by exceptions to rules.” [This relates back to an appropriation denied to (historically black) Alcorn College of $9,000 that was reversed and raised to a $14,000 appropriation once the Mississippi governor “had come in personal contact with the Negro president of Alcorn College – and liked him.”]

“The unfortunate result of the dominance of the single idea of the Negro upon politics has been to benumb the South intellectually; to stifle free thought and free speech. Let a man advance a new issue and if the party leaders do not favor it they have only to cry out “Negro,” twisting the issue so as to emphasize its Negro side, … and the independent thinker is crushed.” [This is applicable, today, to so many other issues than race, as politicians appeal to single-minded, single-issue voters.]

“After the war, the North, in one form or another, poured much money into the South for teaching the Negroes. … in the long run there can be no real education which is not self-education; outside influences may help, … but until a state—like a man—is inspired with a desire for education and a willingness to make sacrifices to get it, the people will not become enlightened.”

”There is no sudden or cut-and-dried solution of the Negro problem, or of any other problem. Men are forever demanding formulae which will enable them to progress without effort. They seek to do quickly by medication what can only be accomplished by deliberate hygiene. ... A problem that has been growing for two hundred and fifty years in America, and for thousands of years before that in Africa, warping the very lives of the people concerned, changing their currents of thought as well as their conduct, cannot be solved in forty years. Why expect it? …

“It will seem trite, but it is eternally true: the cause of the race ‘problem’ and most other social problems is simply lack of understanding and sympathy between man and man. And the remedy is equally simple – a gradual substitution of understanding and sympathy for blind repulsion and hatred.”

This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

It might have been rather shocking to read what led me to this book: Ray Stannard Baker’s two articles documenting the lynchings in the South and North from 1904. I was taught, in the ‘60s, that lynchings were the tool of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to keep the black man in his place. I was perfectly comfortable with this explanation for more than sixty years until Mr. Baker revealed a more knowledgeable, research-driven side to the causes behind mob violence in such an evil form. His stories were horrifying. I wanted to know more.

My first clue that there was more to the story was when I read that: (1) this form of mob justice also occurred in the North, (2) 1 out of every 3 lynchings was a white person, and (3) fifty-one were women. For me, these statistics made these “mobs for justice”—while no less reprehensible—less-easily generalized.

Here is Mr. Baker’s discussion on one set of statistics:

My first clue that there was more to the story was when I read that: (1) this form of mob justice also occurred in the North, (2) 1 out of every 3 lynchings was a white person, and (3) fifty-one were women. For me, these statistics made these “mobs for justice”—while no less reprehensible—less-easily generalized.

Here is Mr. Baker’s discussion on one set of statistics:

|

“I was astounded by the extraordinary prevalence in all these lynching counties, North as well as South, of crimes of violence, especially homicide, accompanied in every case by a poor enforcement of the law. …

“I am not telling these things with any idea of excusing or palliating the crime of lynching, but with the earnest intent of setting forth all the facts, so that we may understand just what the feelings and impulses of a lynching town really are, good as well as bad. Unless we diagnose the case accurately, we cannot hope to discover effective remedies. … “No, it is not all race prejudice that causes lynchings, even in the South. One man in every six lynched in this country in 1903 - the year before the lynching I am describing – was a white man. It is true that a Negro is often the victim of mob law where a white man would not be, but the chief cause certainly seems to lie deeper, in the widespread contempt of the courts, and the unpunished subversion of the law in this country, both South and North. … |

“I have called attention to the fact that the lynching town nearly always has a previous bad record of homicide. Disregard for the sacredness of human life seems to be in the air of these places. … a mob is the method by which good citizens turn over the law and the government to the criminal or irresponsible classes. … [and] once released, the spirit of anarchy spreads and spreads, not subsiding until it has accomplished its full measure of evil [emphasis added].”

Have we as a society truly tried to look into what was the cause of the riots we saw going on for months in Portland or the attack on the Capital? Or are we continuing to follow our human nature and do as Mr. Baker wrote in 1908, “blame men, not conditions?” Is not “society” responsible for its environment? Are we relearning what this journalist discovered more than a century ago: that lawlessness breeds more extensive, wide-spread, and more destructive forms of lawlessness? That we, as a society must—at all times and under all conditions—examine each case to ensure that justice is served in a timely fashion – and communicated to society?

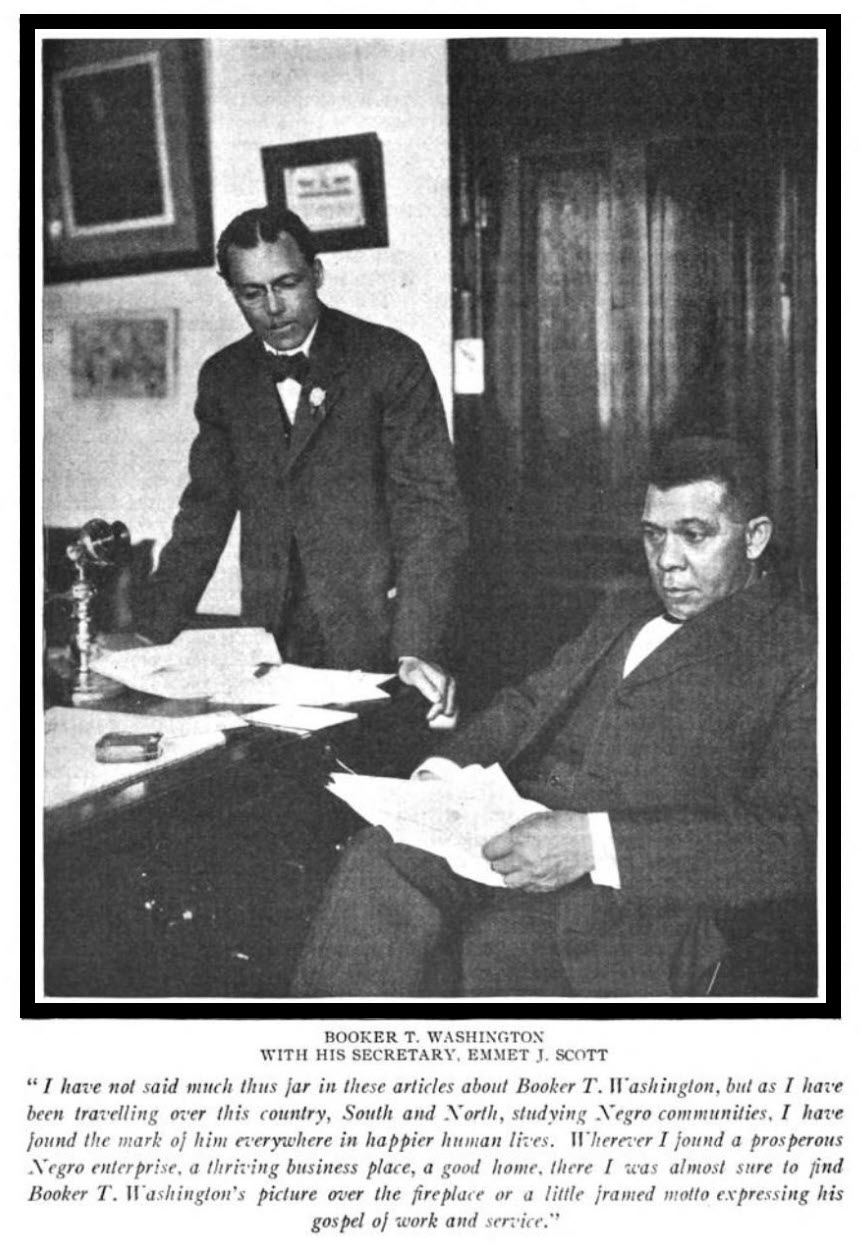

Having just read Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, and Character Building (links to reviews) I was amazed of how articulately Mr. Baker stated what I felt reading Mr. Washington’s book (you will have to read Following the Color Line to understand why I am using “Mr.” instead of “Dr.” It is an amazing insight into society that has, gratefully, changed … So, it is “Mr.” Washington to me. The story is on pages 63 and 64 in The Color Line).

Have we as a society truly tried to look into what was the cause of the riots we saw going on for months in Portland or the attack on the Capital? Or are we continuing to follow our human nature and do as Mr. Baker wrote in 1908, “blame men, not conditions?” Is not “society” responsible for its environment? Are we relearning what this journalist discovered more than a century ago: that lawlessness breeds more extensive, wide-spread, and more destructive forms of lawlessness? That we, as a society must—at all times and under all conditions—examine each case to ensure that justice is served in a timely fashion – and communicated to society?

Having just read Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, and Character Building (links to reviews) I was amazed of how articulately Mr. Baker stated what I felt reading Mr. Washington’s book (you will have to read Following the Color Line to understand why I am using “Mr.” instead of “Dr.” It is an amazing insight into society that has, gratefully, changed … So, it is “Mr.” Washington to me. The story is on pages 63 and 64 in The Color Line).

|

The American Magazine, May 1908 from Ray Stannard Baker's "An Ostracized Race in Ferment"

|

“It is the doctrine [Mr. Booker T. Washington’s doctrine] of the opportunist and optimist: peculiarly, indeed, the doctrine of the man of the soil, who has come up fighting, dealing with the world, not as he would like to have it, but as it overtakes him. Many great leaders have been like that: Lincoln was one.

“They have the simplicity and patience of the soil, and immense courage and faith. To prevent being crushed by circumstances they develop humor; they laugh off their troubles. Washington has all of these qualities of the common life: he possesses in high degree what someone has called “great commonness.” And finally he has a simple faith in humanity, and in the just purposes of the Creator of humanity. “Being a hopeful opportunist Washington takes the Negro as he finds him, often ignorant, weak, timid, surrounded by hostile forces, and tells him to go to work at anything, anywhere, but go to work, learn how to work better, save money, have a better home, raise a better family.” I truly admired the insight in the section entitled, “What Slavery Did.” Mr. Baker discusses democracy vs aristocracy. This is such a critical distinction to understand: slavery arrested the economic growth and political development of both black and white communities across the South. |

If we could acknowledge this defect in racism might this not bring us together, because one race cannot keep another race down without contaminating the hopes, the dreams, and the respect of its own.

“This is what slavery did: It enabled a comparatively few men (only about one in ten of the white men of the South was a slave-owner or slave-renter) to control eleven states of the Union, to monopolize learning, to hold all the political offices, to own most of the good land and nearly all of the wealth.

“Not only did it keep the Negro in slavery, but nine-tenths of the white people (the so-called “poor whites,” whom even the Negroes despised) were hardly more than peasants or serfs. It was in many ways a charming aristocracy, but it was doomed from the beginning.”

The South found itself after the war in a “Divided, United States,” and Andrew Johnson, the replacement President, was, unlike Abraham Lincoln, going to punish the South. Using the excerpt above, one has to observe that payment could have never been extracted without negatively affecting the poorest of the poor southern inhabitants: black and white.

“Revolutions such as the Civil War change names: they do not at once change human relationships. Mankind is reconstructed not by proclamations or legislation or military occupation, but by time, growth, education, religion, thought.

“When the South got on its feet again after Reconstruction and took account of itself, what did it find? It found 4,000,000 ignorant Negroes changed in name from “slave” to “freeman,” but not changed in nature. It found the poor whites still poor whites; and the aristocrats, although they had lost both property and position, were still aristocrats. For values, after all, are not outward, but inward: not material, but spiritual. It was as impossible for the Negro at that time to be less than a slave as it was for the aristocrat to be less than an aristocrat. And this is what so many legal-minded men will not or cannot see.

“What happened?

“Exactly what might have been predicted. Southern society had been turned wrong side up by force, and it righted itself again by force. The Ku Klux Klan, the Patrollers, the Bloody Shirt movement, were the agencies (violent and cruel indeed, but inevitable) which readjusted the relationships, put the aristocrats on top, the poor whites in the middle, and the Negroes at the bottom. In short, society instinctively reverted to its old human relationships.

“I once saw a man shot through the body in a street riot. Mortally wounded, he stumbled and rolled over in the dust, but sprung up again as though uninjured and ran a hundred yards before he finally fell dead.

“Thus the Old South, though mortally wounded, sprung up and ran again.”

When I read this excerpt, I thought of the Marshall Plan after World War II. America's leadership did the right thing healing the wounds after that war. If only, we could go back and do the same after the World War I, maybe we could have prevented this follow-on world war. Or maybe, going back another half-century, our own country would have been better served if we had healed our own wounds after our Civil War.

May we find peace, and cheers,

- Pete

“This is what slavery did: It enabled a comparatively few men (only about one in ten of the white men of the South was a slave-owner or slave-renter) to control eleven states of the Union, to monopolize learning, to hold all the political offices, to own most of the good land and nearly all of the wealth.

“Not only did it keep the Negro in slavery, but nine-tenths of the white people (the so-called “poor whites,” whom even the Negroes despised) were hardly more than peasants or serfs. It was in many ways a charming aristocracy, but it was doomed from the beginning.”

The South found itself after the war in a “Divided, United States,” and Andrew Johnson, the replacement President, was, unlike Abraham Lincoln, going to punish the South. Using the excerpt above, one has to observe that payment could have never been extracted without negatively affecting the poorest of the poor southern inhabitants: black and white.

“Revolutions such as the Civil War change names: they do not at once change human relationships. Mankind is reconstructed not by proclamations or legislation or military occupation, but by time, growth, education, religion, thought.

“When the South got on its feet again after Reconstruction and took account of itself, what did it find? It found 4,000,000 ignorant Negroes changed in name from “slave” to “freeman,” but not changed in nature. It found the poor whites still poor whites; and the aristocrats, although they had lost both property and position, were still aristocrats. For values, after all, are not outward, but inward: not material, but spiritual. It was as impossible for the Negro at that time to be less than a slave as it was for the aristocrat to be less than an aristocrat. And this is what so many legal-minded men will not or cannot see.

“What happened?

“Exactly what might have been predicted. Southern society had been turned wrong side up by force, and it righted itself again by force. The Ku Klux Klan, the Patrollers, the Bloody Shirt movement, were the agencies (violent and cruel indeed, but inevitable) which readjusted the relationships, put the aristocrats on top, the poor whites in the middle, and the Negroes at the bottom. In short, society instinctively reverted to its old human relationships.

“I once saw a man shot through the body in a street riot. Mortally wounded, he stumbled and rolled over in the dust, but sprung up again as though uninjured and ran a hundred yards before he finally fell dead.

“Thus the Old South, though mortally wounded, sprung up and ran again.”

When I read this excerpt, I thought of the Marshall Plan after World War II. America's leadership did the right thing healing the wounds after that war. If only, we could go back and do the same after the World War I, maybe we could have prevented this follow-on world war. Or maybe, going back another half-century, our own country would have been better served if we had healed our own wounds after our Civil War.

May we find peace, and cheers,

- Pete