IBM Case Study: The Importance of Sales Productivity

|

|

Date Published: June 8, 2021

Date Modified: May 1, 2024 |

George Ed Smith, the president of Royal Typewriter who took his corporation to the top of its industry, believed a great salesman should ask this of any company and its leadership:

“What do you know about selling? My success will depend 25 per cent upon what I do and 75 per cent on what you have already done to make selling possible. Can you give me any assurance that I shall not waste my time with you? … My success is bound up in the thorough understanding of two principles: (1) That what you have to sell is worthwhile and meets a need, and (2) that you have such confidence in what you have to sell, and therefore in your own integrity, that you can inspire a similar confidence in the man before you.”

“What do you know about selling? My success will depend 25 per cent upon what I do and 75 per cent on what you have already done to make selling possible. Can you give me any assurance that I shall not waste my time with you? … My success is bound up in the thorough understanding of two principles: (1) That what you have to sell is worthwhile and meets a need, and (2) that you have such confidence in what you have to sell, and therefore in your own integrity, that you can inspire a similar confidence in the man before you.”

Any successful corporation over the long term requires a chief executive with the mindset of a salesman-in-chief. As noted above, Royal Typewriter had George Ed Smith. Firestone Tire Company had Harvey S. Firestone. General Motors had Alfred P. Sloan. Lord & Taylor had Dorothy Shaver.

Sales morale is the governor that steadies the sales productivity engine, and it is the responsibility of the corner office to keep sales’ morale up and its output constantly growing under variable economic conditions.

Sales morale is the governor that steadies the sales productivity engine, and it is the responsibility of the corner office to keep sales’ morale up and its output constantly growing under variable economic conditions.

George Ed Smith was a chief executive officer who was a Salesman-in-Chief.

Sales Productivity Measures the Effectiveness of a Corner Office

- How Important Is Selling to a Corporation?

- Eight Decades of IBM Sales Productivity Growth Hits a Wall

- Two Critical IBM Sales Productivity Inflection Points

- Two Decades of IBM Declining Sales Productivity

- The Lack of Correlation Between IBM Sales and Profit Productivity

How Important Is Selling to a Corporation?

To answer this question, ask, “How important is it for a car to move?”

When an individual shows up to buy a car, one of the first questions asked is, “How reliable is it?” Of course, no one adds “at moving” because this is understood to be the most basic function of a car. If the answer is that it is reliable (moving being assumed) the individual quickly asks more numerous, less important questions: How many miles does it have on it? What condition are the tires in? What type of music system does it have? And in Texas, the all-important, does the air conditioning work? Of course, these are all relevant questions until the individual finally asks for the keys and says, “Let’s take it for a drive!” To which the seller says, “But it won’t move.” The buyer, a little irritated, replies, “Better call a salvage yard.”

So it is, with a corporation. The corporation’s most basic function that too many analysts forget to consider is, “Can the corporation move product, and if it moves product, can it maintain its momentum during demanding economic conditions?” A corporation that can’t sell and, importantly, sell productively will be attacked by the competition, acquired by a more efficient organization, or sold off in pieces.

When an individual shows up to buy a car, one of the first questions asked is, “How reliable is it?” Of course, no one adds “at moving” because this is understood to be the most basic function of a car. If the answer is that it is reliable (moving being assumed) the individual quickly asks more numerous, less important questions: How many miles does it have on it? What condition are the tires in? What type of music system does it have? And in Texas, the all-important, does the air conditioning work? Of course, these are all relevant questions until the individual finally asks for the keys and says, “Let’s take it for a drive!” To which the seller says, “But it won’t move.” The buyer, a little irritated, replies, “Better call a salvage yard.”

So it is, with a corporation. The corporation’s most basic function that too many analysts forget to consider is, “Can the corporation move product, and if it moves product, can it maintain its momentum during demanding economic conditions?” A corporation that can’t sell and, importantly, sell productively will be attacked by the competition, acquired by a more efficient organization, or sold off in pieces.

The last of these is already happening at IBM.

Initially it was the list of acquisitions that was getting long—an average of almost one acquisition a month for the last 22 years. Second thoughts about these 224 acquisitions of “higher value” are adding significant weight to the divestiture—the salvage yard—side of the scales.

Initially it was the list of acquisitions that was getting long—an average of almost one acquisition a month for the last 22 years. Second thoughts about these 224 acquisitions of “higher value” are adding significant weight to the divestiture—the salvage yard—side of the scales.

Selling productively is a critical corporate metric that is assumed and rarely discussed. Analysts have ignored the very life breath of a corporation: its ability to acquire a customer, retain a customer and sell more to a satisfied customer. If a corporation can’t deliver revenue reliably and efficiently it has the same value as a car that can’t move.

Without productive selling, it is not a matter of “if” but “when” the corporation will, figuratively, run out of petrol. For the first eight decades of IBM’s existence, its senior executives understood this fact of corporate life.

Without productive selling, it is not a matter of “if” but “when” the corporation will, figuratively, run out of petrol. For the first eight decades of IBM’s existence, its senior executives understood this fact of corporate life.

Eight Decades of IBM Sales Productivity Growth Hits a Wall

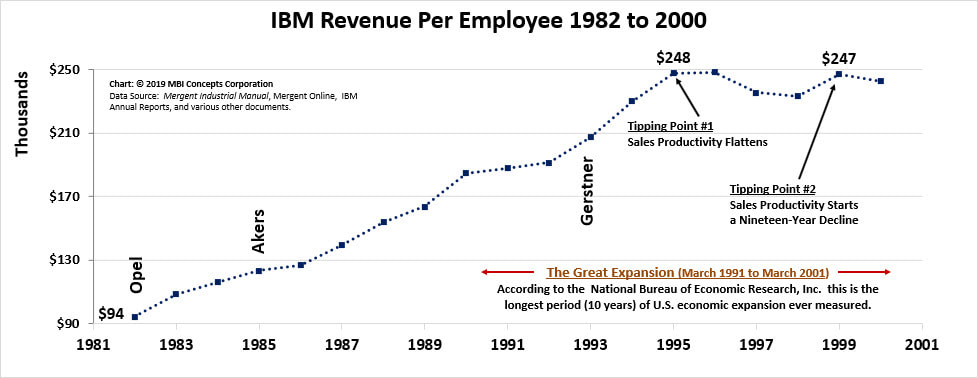

This chart reflects the history of IBM’s sales productivity. Before 1995, the last time the corporation experienced two yearly, back-to-back sales productivity declines was the trough of the Great Depression. This is a period of six decades with twelve recessions and the #1, #3, #5, #6, #7, #10 and #12 largest—in real total returns—stock market declines in U.S. Stock Market history. There was only one major, long-term sales productivity decline prior to 1995: The Recession of 1920-21. Watson Sr. learned during this time how to “not” handle an economic downturn when he slashed salaries, laid off critical personnel and brought research and development into new products to a standstill.

These layoff practices, once disavowed by corporate tradition, were reinstated in 1993, and the results since are paralleling Watson Sr.’s results in the aftermath of 1920-21. The major difference is that the corner office in the 1920s recognized and corrected its mistakes so that the corporation recovered in time to survive the Great Depression. Louis V. Gerstner and his successors, unlike Thomas J. Watson Sr., have never admitted their mistake, and this is a great disservice to Corporate America in general and every employee of the corporation in particular.

So, the mistakes continue, and their effects are exaggerated.

These layoff practices, once disavowed by corporate tradition, were reinstated in 1993, and the results since are paralleling Watson Sr.’s results in the aftermath of 1920-21. The major difference is that the corner office in the 1920s recognized and corrected its mistakes so that the corporation recovered in time to survive the Great Depression. Louis V. Gerstner and his successors, unlike Thomas J. Watson Sr., have never admitted their mistake, and this is a great disservice to Corporate America in general and every employee of the corporation in particular.

So, the mistakes continue, and their effects are exaggerated.

Two Critical IBM Sales Productivity Inflection Points

In 1995, after only two years under Mr. Gerstner’s leadership, sales productivity flattened in the fifth year of a tremendous ten-year economic expansion. In November 2001, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) referred to this economic expansion as the longest economic expansion in its chronology which started in 1854. In the chart below, it is the time frame annotated as “The Great Expansion.” This great, economic expansion marks for IBM, two critical sales-productivity, downward inflection points: in 1995, when sales productivity flattened, and in 1999, when sales productivity began its current twenty-three-year decline.

This chart documents IBM's two critical sales-productivity, downward inflection points: in 1995, when sales productivity flattened, and in 1999, when sales productivity began its current twenty-three-year decline.

Evaluating change requires the passage of time and a variety of perspectives. Given enough time, long-term positive or negative trends can be associated with their cause, and given enough perspectives, historical bias can be overcome. The former condition, though, tests the patience of the impatient, and the latter condition is abhorrent to the arrogant. Unfortunately, the print wasn’t even dry on Lou’s retirement papers before he wrote of his unequivocal success in Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance. This is how to preserve a personal legacy, not write an unbiased evaluation of corporate history. Chief executive officers' self-evaluations (now followed by Virginia (Ginni) M. Rometty's book) need further review but Gerstner's autobiography, especially, because under his leadership sales productivity not only flattened but began what is now a two-decade long decline.

Of course, under his leadership the corporation survived a near-death experience in 1992-93, but it had survived similar experiences in 1914-15, 1920-21, 1932-33 and 1964-65. In 1932-33 and 1964-65, IBM’s culture covered for its chief executives. In 1992-93, IBM's culture even compensated for Louis V. Gerstner—an “outsider.” It gave Lou an opportunity to succeed—at least initially. Unfortunately, under his leadership, the productivity of the sales culture which had churned ever onward through recessions, depressions, and technological transitions, flattened and turned ever downward during the greatest economic and technological expansion in U. S. history.

Of course, under his leadership the corporation survived a near-death experience in 1992-93, but it had survived similar experiences in 1914-15, 1920-21, 1932-33 and 1964-65. In 1932-33 and 1964-65, IBM’s culture covered for its chief executives. In 1992-93, IBM's culture even compensated for Louis V. Gerstner—an “outsider.” It gave Lou an opportunity to succeed—at least initially. Unfortunately, under his leadership, the productivity of the sales culture which had churned ever onward through recessions, depressions, and technological transitions, flattened and turned ever downward during the greatest economic and technological expansion in U. S. history.

Two Decades of IBM Declining Sales Productivity

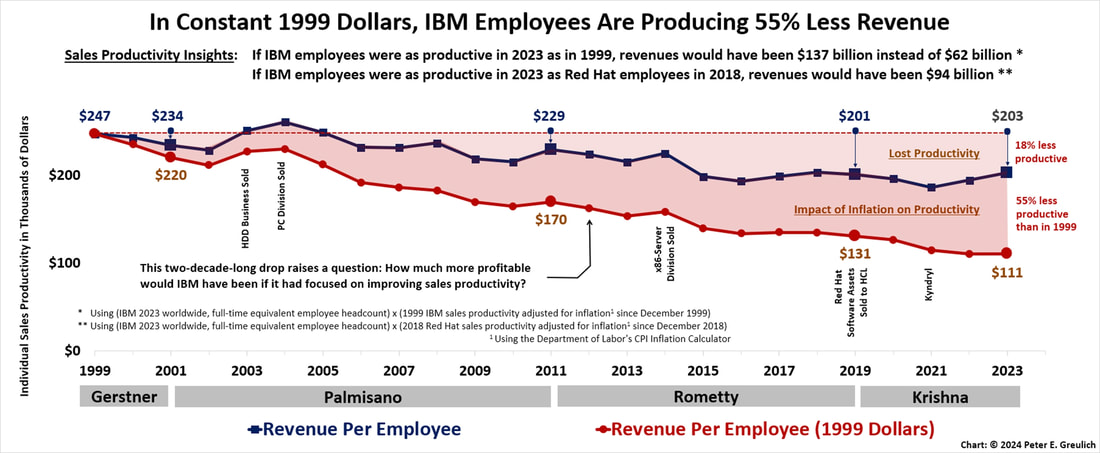

Some apologists for the corporation’s chief executives explain this poor sales performance and a myriad of other operational problems on globalization, but this is a smoke screen. In fact, sales productivity was falling long before IBM entered the globalization free-for-all. In fact, the corporation used globalization to pad profits and these actions exacerbated an already easily identifiable problem—it was losing its ability to move product productively.

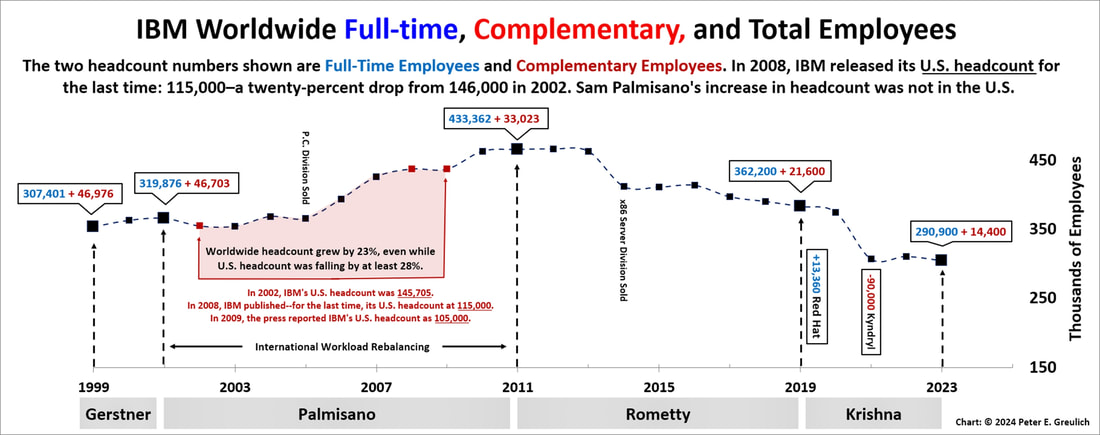

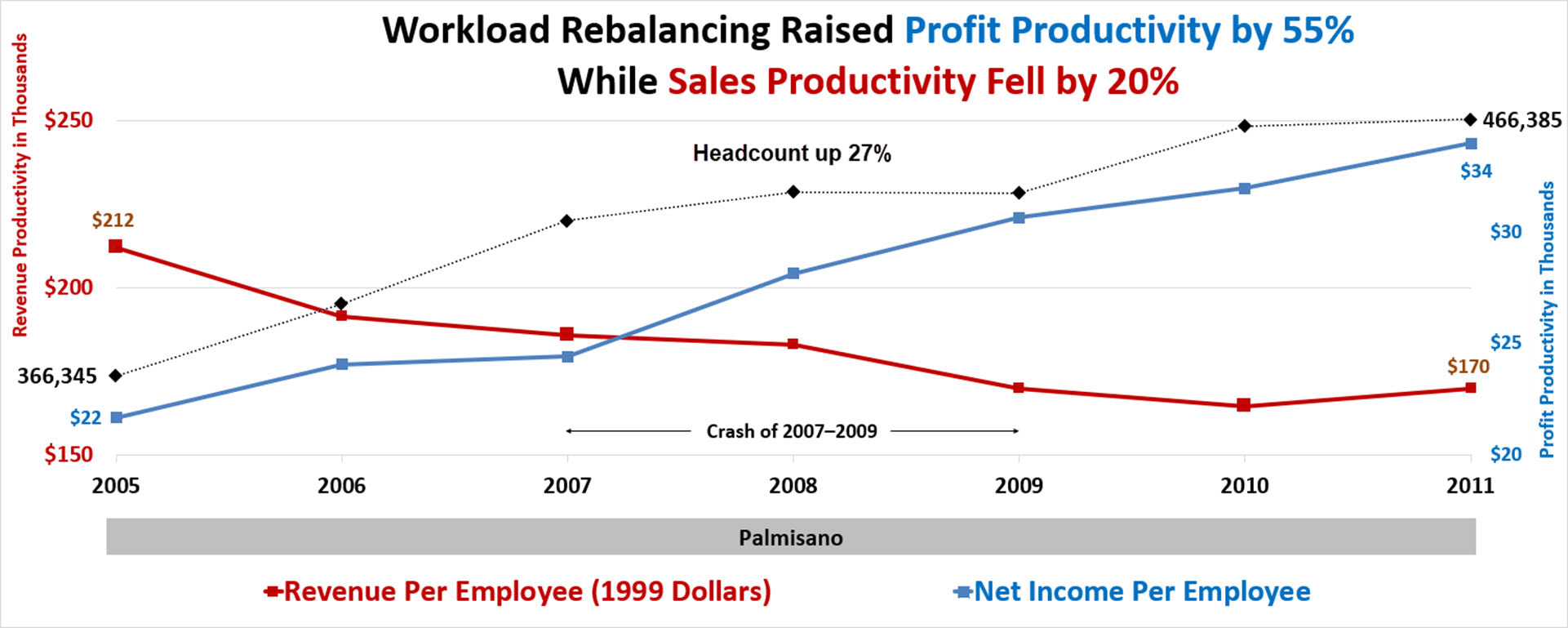

IBM’s massive exploitation of globalization can be seen in the headcount increases starting in 2002 under Samuel J. Palmisano. This was worldwide, workload rebalancing at its most expansive . . . and most expensive to U.S. and Western Europe employees.

This chart clearly documents that Sam Palmisano grew IBM's headcount at the expense of United States employees.

IBM increased its total worldwide headcount by 100,000—twenty-seven percent—right through the Great Recession, while it released—at least—twenty-two percent of its U. S. workforce. In a strike against transparency IBM stopped releasing its U. S. employment numbers in 2009. This is the reason the full percentage drop in the U. S. workforce can’t be reliably computed, but it is probably well north of double the twenty-two percent. [It is important to the author to note that he does not believe that any one country has a monopoly on “better workers.” The point being made here is that poor human relations policies eventually have the same negative effect worldwide: they reduce employee engagement regardless of city, county, country, continent or culture.]

This five-year period reflects the executives’ decision to replace the corporation’s highly productive and therefore highly paid U. S. and European workers with lower paid workers from around the world. This resulted in lower sales productivity, but it increased profits to feed the first of Samuel J. Palmisano’s five-year, earnings-per-share roadmaps. The strategy, though, fell short of providing enough profits to fund the second roadmap. Why? The management team invested the excess profits from workload rebalancing in their own stock.

Since 1995, instead of investing in making their people more productive, their processes more effective and their products more valuable, they invested $201,000,000,000 in paper. The drag on profit productivity that caused the failure of the second roadmap was falling sales productivity. The effect of Louis V. Gerstner’s, Samuel J. Palmisano’s and Virginia M. Rometty’s poor human relations practices and unwise investments in paper instead of people, processes and products are the reason for the initial flattening of productivity in 1995 and its failure to recover for the breadth of the 21st Century. These practices flew under the standards of “Workload Rebalancing” and “Maximizing Shareholder Value” even as sales productivity dropped incessantly.

Profits from these highly questionable tactics drove the earnings-per-share roadmaps until 2014, at which time these strategies proved unsustainable, and Virginia M. Rometty ended the futile effort.

Of course, the poor strategies and human relations practices continued.

This five-year period reflects the executives’ decision to replace the corporation’s highly productive and therefore highly paid U. S. and European workers with lower paid workers from around the world. This resulted in lower sales productivity, but it increased profits to feed the first of Samuel J. Palmisano’s five-year, earnings-per-share roadmaps. The strategy, though, fell short of providing enough profits to fund the second roadmap. Why? The management team invested the excess profits from workload rebalancing in their own stock.

Since 1995, instead of investing in making their people more productive, their processes more effective and their products more valuable, they invested $201,000,000,000 in paper. The drag on profit productivity that caused the failure of the second roadmap was falling sales productivity. The effect of Louis V. Gerstner’s, Samuel J. Palmisano’s and Virginia M. Rometty’s poor human relations practices and unwise investments in paper instead of people, processes and products are the reason for the initial flattening of productivity in 1995 and its failure to recover for the breadth of the 21st Century. These practices flew under the standards of “Workload Rebalancing” and “Maximizing Shareholder Value” even as sales productivity dropped incessantly.

Profits from these highly questionable tactics drove the earnings-per-share roadmaps until 2014, at which time these strategies proved unsustainable, and Virginia M. Rometty ended the futile effort.

Of course, the poor strategies and human relations practices continued.

The Lack of Correlation Between IBM Sales and Profit Productivity

Some financially minded executives at IBM have pontificated for decades that a great salesman is an individual who can sell anything. This is the definition of a used-car shyster tasked with clearing an asphalt parking lot of dilapidated jalopies, not of a productive salesman within the technology industry. The former is not concerned with repeat sales and returning customers because there is always another used-car lot just up the street. The latter sells what fills a real need, and higher productivity is achieved through follow-on sales through ever stronger customer relationships.

This chart poses the question: "How did IBM increase profit productivity so dramatically in the face of falling sales productivity?"

Additionally, IBM’s divestitures are destroying relationships with critical, internal customer recommenders as they come to understand that any product may be sold off in any quarter, not because it isn’t profitable, but because it isn’t “profitable enough.” It is hard for a salesman’s words to overcome these corporate actions.

The ethical dilemma each salesman at IBM faces waking up each day is, “Should he or she even try?”

This affects every salesman’s productivity.

It is now possible to answer George Ed. Smith’s two inquiries. A salesman should be careful about wasting their time with this corporation because after two decades of acquisitions and divestitures, the corporation does not have products that are worthwhile and meet a need, and its products do not inspire confidence and integrity in its salesmen.

Thomas J. Watson Sr. put it this way, “Sales morale in any organization is primarily dependent upon the men [or women] at the top and is based on their knowledge of the business, their personality, their integrity and their moral character.”

Sales productivity has been and remains a disaster; It is a disaster of the corner offices’ own making.

The ethical dilemma each salesman at IBM faces waking up each day is, “Should he or she even try?”

This affects every salesman’s productivity.

It is now possible to answer George Ed. Smith’s two inquiries. A salesman should be careful about wasting their time with this corporation because after two decades of acquisitions and divestitures, the corporation does not have products that are worthwhile and meet a need, and its products do not inspire confidence and integrity in its salesmen.

Thomas J. Watson Sr. put it this way, “Sales morale in any organization is primarily dependent upon the men [or women] at the top and is based on their knowledge of the business, their personality, their integrity and their moral character.”

Sales productivity has been and remains a disaster; It is a disaster of the corner offices’ own making.

Opinion of the Author Concerning IBM Sales Productivity

The one measurement that evaluates a corporation from end-to-end is sales productivity. Is the product competitive? Is the product positioned properly in a market clamoring to buy? Is the marketing organization creating awareness and generating demand? Is the support organization providing necessary information in a timely fashion? In the technology industry, is the testing organization ensuring that customers aren’t the final test bed for every new release? Is the corporation aware of the customers’ key objections and is its sales enablement organization training its customer-facing individuals to overcome these objections? Fundamentally, is every employee a salesman?

A thorough study of sales productivity will map out the internal organs of an entire corporation, and it will determine how well or poorly they are functioning. It determines why a corporation cannot move its products. This is the 75% that George Ed Smith wanted in place before he sent his salesmen to stand in front of a potential customer. They were not tasked with selling a product but sold the integrity of a corporation that would not let a customer down.

Corporate integrity requires integrity in the corner office.

Corporate America—not just IBM—needs more Salesmen-in-Chiefs.

A thorough study of sales productivity will map out the internal organs of an entire corporation, and it will determine how well or poorly they are functioning. It determines why a corporation cannot move its products. This is the 75% that George Ed Smith wanted in place before he sent his salesmen to stand in front of a potential customer. They were not tasked with selling a product but sold the integrity of a corporation that would not let a customer down.

Corporate integrity requires integrity in the corner office.

Corporate America—not just IBM—needs more Salesmen-in-Chiefs.