The $1,000-A-Day Chief Executive Officer

Tom Watson: The Thousand-Dollar-A-Day Man

- The Origins and Idiosyncrasies of the Revenue Act of 1934

- A Front-Page, Headline-Making, Not-So-Timely, Chaotic, Public Event

- Watson's Salary Reductions and the Effect of Taxes

The Origins and Idiosyncrasies of the Revenue Act of 1934

|

The Revenue Act of 1934 required the U.S. Treasury to publish the names of corporate officials making more than $15,000 in salaries, commissions and bonuses. Not included were incomes from dividends, proprietorships, partnerships, rents or royalties; neither did the act account for salaries received from multiple corporations. Many Hollywood stars formed corporations to produce their movies and then received their earnings as dividends.

The report did not measure wealth, as the nation’s richest families—the Du Ponts, the Rockefellers, the Fords and the Morgans—earned their incomes through capital investments. With the advent of World War II, an individual earning a $100,000 salary and producing vital war materials could be brought into the public eye while another individual receiving $1,000,000 from investments and paying little in taxes to support the war would go unnoticed.

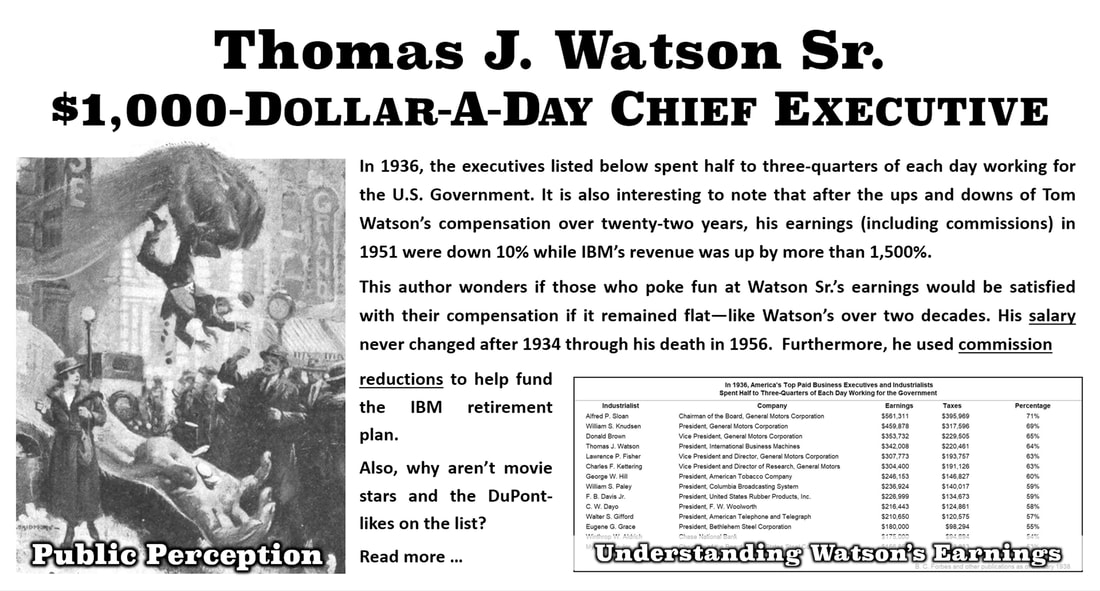

A Front-Page, Headline-Making, Not-So-Timely, Public Event Surrounded by Chaos At times the approximately eleven-hundred page report listed almost fifty thousand individuals from more than eight thousand corporations. It could be a chaotic scene when the report was initially released, as reporters pushed and shoved to be the first in line for a front-page story—revealing the year’s highest paid individual, industrialist, movie mogul, entertainer or woman.

The chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, after seeing the commotion with the release of the 1936 report, temporarily suspended access, commenting that the list might get “disarranged or lost.” The report would also be updated as corporations closed out their fiscal years, so the highest paid individual could be very fluid.

|

For example, a business section headline of the New York Post on May 6, 1936, read, “Watson’s Pay of $303,813 Tops ’35 List.” Less than thirty days later, the headline of the same paper read, “Sloan Highest Paid Executive with $374,505.” The final 1935 winner was actually William Randolph Hearst at $500,000.

Watson Salary Reductions and the Effect of Taxes

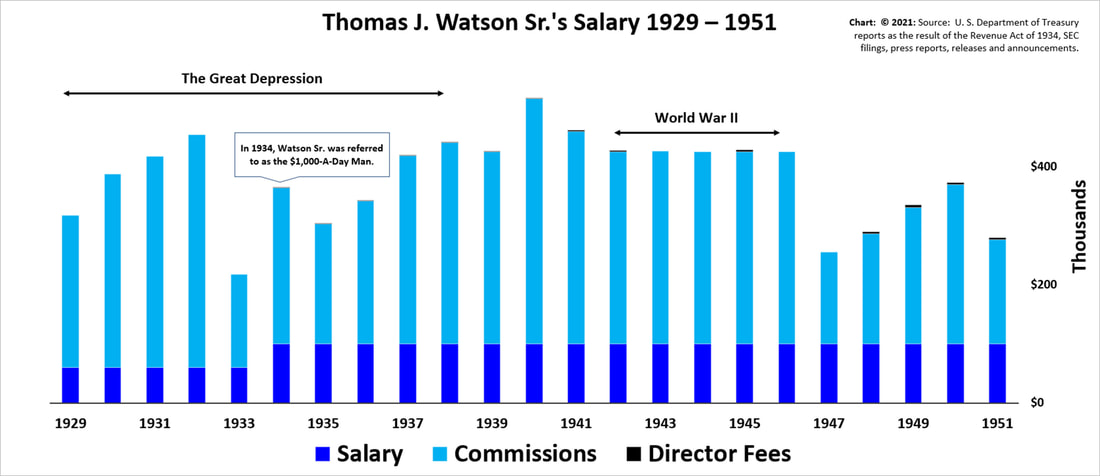

In April 1942, Watson asked the board of directors to modify his employment contract. Refusing to profit personally from the manufacture of war munitions, he reduced his profit-sharing compensation from 5% to 2.5%. He made the new contract retroactive to 1941. It was later determined that it was too difficult to determine the increase in general business attributable to the war, so he requested that his commissions not exceed that of 1939—a time when the company had no war business. This is easily visualized in the chart below.

Reading newspapers of the time, it appears that Watson Sr.’s salary was more fodder for letters to the editor than it was the subject matter of serious editorials.

It is also interesting that after the ups and downs of his salary over twenty-two years Watson’s earnings (including commissions) in 1951 were down 10% while IBM’s revenue was up by more than 1,500%. One has to wonder if authors who poke fun at Watson Sr.’s earnings would be satisfied with their salary if it remained flat for seventeen years and, when commissions were considered, decreased over two decades.

Reading newspapers of the time, it appears that Watson Sr.’s salary was more fodder for letters to the editor than it was the subject matter of serious editorials.

It is also interesting that after the ups and downs of his salary over twenty-two years Watson’s earnings (including commissions) in 1951 were down 10% while IBM’s revenue was up by more than 1,500%. One has to wonder if authors who poke fun at Watson Sr.’s earnings would be satisfied with their salary if it remained flat for seventeen years and, when commissions were considered, decreased over two decades.

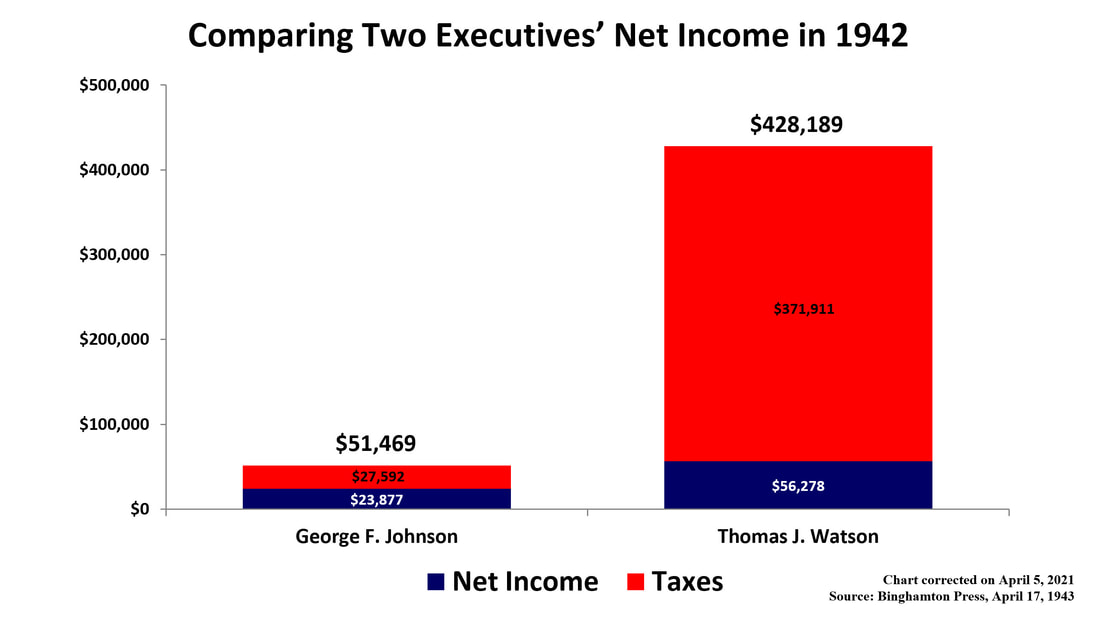

Because of the war-time tax increases, a gross salary wasn't always what it seemed as proven by this analysis done in the Binghamton Press of two of its leading citizens: George F. Johnson (Endicott-Johnson) and Thomas J. Watson (IBM).

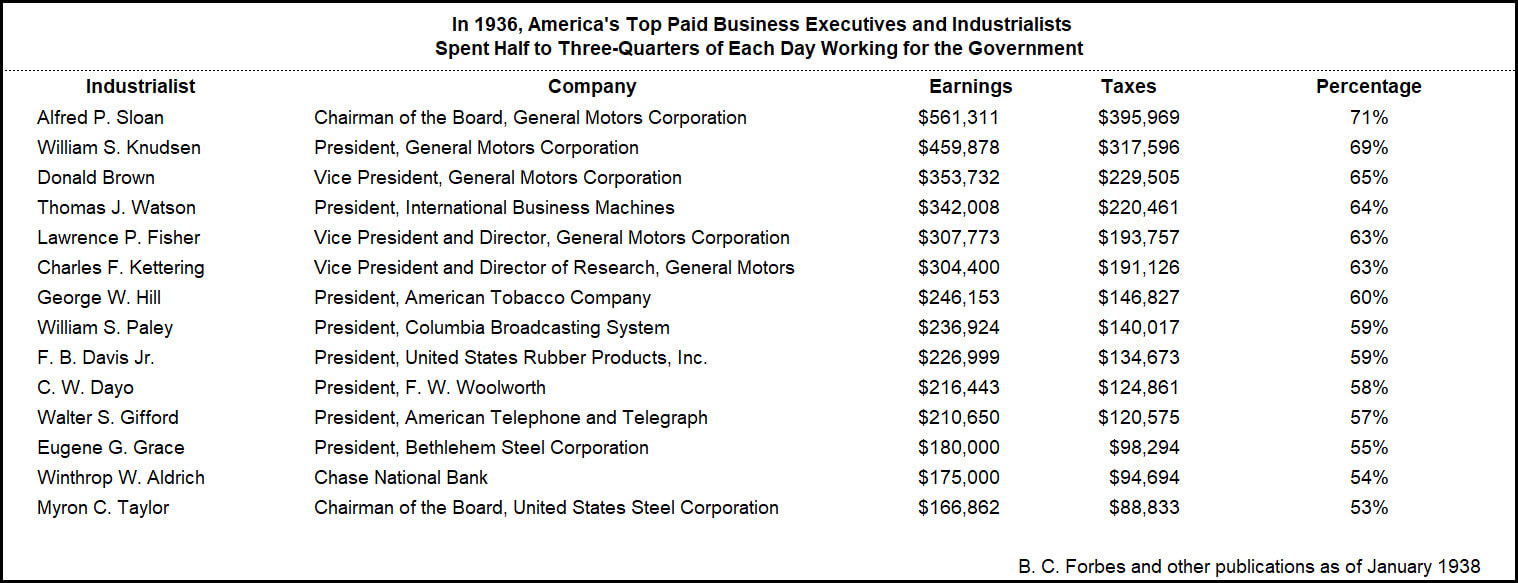

This chart shows that the chief executives in 1936 when their salaries were being analyzed were actually spending half to three-quarters of each day working for the government.

It does seem like there is always "more to the story," doesn't it?

Cheers,

- Peter E.

Cheers,

- Peter E.