A Review of "George Eastman" by Carl Ackerman

|

|

Date Published: December 20, 2020

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

George Eastman (1854) was born into an earlier generation than Thomas J. Watson Sr. (1874). George Eastman’s war was World War I. Tom Watson’s war was World War II. The Eastman Kodak Company founder was an icon within his Genesee Valley, an area that included the headquarters and home of Eastman Kodak situated in the valley’s nineteenth-century financial epicenter—Rochester, N.Y.

Long before Tom Watson was recognized within the business and social circles of New York, the Eastman Kodak Company industrialist had achieved both local and international name recognition through his company’s slogan for the Kodak Camera, “You press the button … we do the rest.” George Eastman paved the way for American corporate growth through massive international connections.

Watson recognized him as one of the 19th Century’s greatest industrialists, internationalists and philanthropists. At the end of this review, be sure and follow the link provided to read the Slice of Life Story by Peter E. Greulich: "A 'Thank You' Becomes 'Goodbye' for a Great American Industrialist."

It is a wonderful piece of American business history.

Long before Tom Watson was recognized within the business and social circles of New York, the Eastman Kodak Company industrialist had achieved both local and international name recognition through his company’s slogan for the Kodak Camera, “You press the button … we do the rest.” George Eastman paved the way for American corporate growth through massive international connections.

Watson recognized him as one of the 19th Century’s greatest industrialists, internationalists and philanthropists. At the end of this review, be sure and follow the link provided to read the Slice of Life Story by Peter E. Greulich: "A 'Thank You' Becomes 'Goodbye' for a Great American Industrialist."

It is a wonderful piece of American business history.

A Review of George Eastman by Carl W Ackerman

- A Summary of Reviews from March 1930

- Selected Quotes and Insights from "George Eastman"

- The Author's Thoughts and Perspective

A Summary of Reviews from March 1930

Within a few months of the publication of George Eastman there were over 300 reviews. For the times, this was an amazing acknowledgement of the industrialist’s name recognition around the world.

One reviewer commented that “although the biography covers 495 pages, it must of necessity be incomplete because Mr. Eastman’s life has been crowded with events.” Most were impressed that Mr. Eastman had granted access to his sixty-one years of personal files that included more than one hundred thousand letters. This was proof to most reviewers that this was an “official” biography and well-grounded in fact. Many were fascinated to discover the multi-faceted man behind the company: inventor, chemist, scientist, manufacturer, merchant, financier and philanthropist as well as businessman.

One reviewer appreciated reading of his aesthetic side which reflected a “keen appreciation of beauty as contrasted with the practical and scientific.”

One reviewer commented that “although the biography covers 495 pages, it must of necessity be incomplete because Mr. Eastman’s life has been crowded with events.” Most were impressed that Mr. Eastman had granted access to his sixty-one years of personal files that included more than one hundred thousand letters. This was proof to most reviewers that this was an “official” biography and well-grounded in fact. Many were fascinated to discover the multi-faceted man behind the company: inventor, chemist, scientist, manufacturer, merchant, financier and philanthropist as well as businessman.

One reviewer appreciated reading of his aesthetic side which reflected a “keen appreciation of beauty as contrasted with the practical and scientific.”

Selected Quotes and Insights from "George Eastman"

Eastman's Belief of Shareholder Involvement in the Business

- When George Eastman initially formed the Eastman Dry Plate Company, he specifically defined the type of owners he desired—it was a similar opinion held by many of the industrialists of his day:

"If you have any friends that want a slice [of the stock offering] let me know. We don't want to place any lots under 2500 and only with people that will expect to let us manage things, keep their chins quiet and draw their divvy when it comes [emphasis added]."

Mapping the Character of American Industrialists

This biography, when considered with other biographies and autobiographies of the day, documents a consistency of thought and action between America’s industrial pioneers. Consider the following:

The Author's Thoughts and Perspective

The book is a rarity among biographies as Carl Ackerman, because of his access to sixty-plus years of George Eastman’s personal letters, could let George Eastman speak for himself through those letters. Carl Ackerman lived up to the standard he set for himself in the Preface by quoting Francis Bacon from The Advancement of Learning:

"It is the true office of history to represent the events themselves together with the counsels, and to leave the observations and conclusions thereupon to the liberty and faculty of every man’s judgement."

"It is the true office of history to represent the events themselves together with the counsels, and to leave the observations and conclusions thereupon to the liberty and faculty of every man’s judgement."

Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning

On George Eastman's Work Ethic and Character

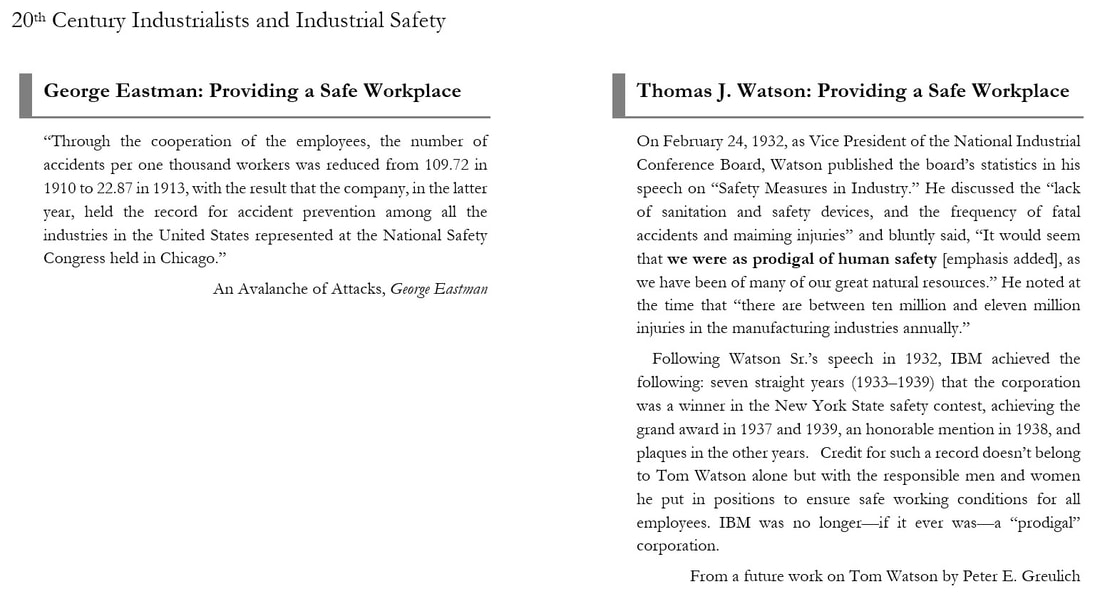

The examples above of the consistency of thought and character between George Eastman, Thomas A. Edison and Thomas J. Watson Sr. is extendible to many of their peers like Alfred P. Sloan Jr. of General Motors, Harvey S. Firestone of Firestone Tire Company, and Gerard Swope and Owen D. Young of General Electric, but for many others – maybe not so much. Not all industrialists fit into the George Eastman mold.

In this revealing paragraph, Carl W. Ackerman makes this point most eloquently:

"Every industrial leader had his own policy, while some had principles.

"Some executives possessed a warmth of human contact that had a medicinal effect upon labor. Others were ruthless. A few were students of human problems. Many gave orders from their pedestals of superiority. Still others philosophized from the safe haven of a resort at the seashore or from the fashionable parade grounds of Europe. Naturally there were many varieties of employers and a like assortment of labor groups."

Even today modern-day chief executives must expect and inspect for basic abilities in their executive team to motivate, stimulate and recognize outstanding abilities in their fellow workers. They must be tireless in the pursuit of the next step forward for their company … their employees … their shareholders … their society.

In this revealing paragraph, Carl W. Ackerman makes this point most eloquently:

"Every industrial leader had his own policy, while some had principles.

"Some executives possessed a warmth of human contact that had a medicinal effect upon labor. Others were ruthless. A few were students of human problems. Many gave orders from their pedestals of superiority. Still others philosophized from the safe haven of a resort at the seashore or from the fashionable parade grounds of Europe. Naturally there were many varieties of employers and a like assortment of labor groups."

Even today modern-day chief executives must expect and inspect for basic abilities in their executive team to motivate, stimulate and recognize outstanding abilities in their fellow workers. They must be tireless in the pursuit of the next step forward for their company … their employees … their shareholders … their society.

On George Eastman the Philanthropist

"Within a year he had given or obligated himself to give very nearly fifty per cent of his cash profits to individuals and institutions. … Eastman was building the foundations for philanthropy and [employee] wage-dividends, employee stock ownership and [employee] co-partnership in industry in the last decade of the nineteenth century [emphasis added]."

Carl W. Ackerman, George Eastman

Although George Eastman gave greatly of his earnings, he did not give his name to any great philanthropic foundation. [His anonymous generosity to MIT, as one example, is shown in the sidebar below entitled, "Mr. Smith is George Eastman"] He tried in many cases to remain anonymous. So, there is no foundation like the Carnegie, Rockefeller or Sloan Foundations to remind individuals today of his benefactions and generosity.

Also, philanthropy is a tough word to define and characterize. At its most simplistic, philanthropy is “the desire to promote the welfare of others.” Men such as George Eastman, Thomas J. Watson, Julius Rosenwald and Gerard Swope promoted the welfare of their fellow man, but the word seems to have taken on a more limiting connotation: marked by the generous donations of money to good causes.

Isn’t a giving of time, philanthropy? Do we need eternal institutions to remember those who gave of their time and earnings to promote the welfare of their fellow human beings?

If we fail to capture in writing the greatness and philanthropy of America’s great industrialists, isn’t the groundwork laid for naysayers and opponents of capitalism who would make “profit” an ugly word, when “greed” is the problem which rears its ugly head in any economic system and should be the overriding concern? [See Footnote #1]

Also, philanthropy is a tough word to define and characterize. At its most simplistic, philanthropy is “the desire to promote the welfare of others.” Men such as George Eastman, Thomas J. Watson, Julius Rosenwald and Gerard Swope promoted the welfare of their fellow man, but the word seems to have taken on a more limiting connotation: marked by the generous donations of money to good causes.

Isn’t a giving of time, philanthropy? Do we need eternal institutions to remember those who gave of their time and earnings to promote the welfare of their fellow human beings?

If we fail to capture in writing the greatness and philanthropy of America’s great industrialists, isn’t the groundwork laid for naysayers and opponents of capitalism who would make “profit” an ugly word, when “greed” is the problem which rears its ugly head in any economic system and should be the overriding concern? [See Footnote #1]

One objection: The book’s – at times – disjointed flow

The flow of the book is at times hard to follow. For instance, there is a chapter entitled “The World War.” It is a wonderful chapter discussing the effects of the war on Eastman Kodak and also its contributions to the war. One would expect to read most of the war information in this chapter. Unfortunately, after discussing the company’s “cost plus 10%” contract with the government, the reader doesn’t discover that George Eastman never intended to make the 10% profit. This is important because after World War I it was discovered that several corporations had abused the “cost plus” policies.

The uplift at Eastman Kodak was for contingencies. It is two chapters later that the reader discovers the company returned its “unused contingencies” to the government.

"The auditor's report showed that upon these contracts the company had profited $182,770.60, and on February 3, 1922, Eastman personally presented a check from the company for this sum to Secretary of War John W. Weeks. Including sundry small refunds, this made a total of $335,389.76, representing war profits which the company returned to the United States Treasury." [See Footnote #2]

This is important information to reveal the motives of George Eastman during World War I: it wasn’t about profits.

The uplift at Eastman Kodak was for contingencies. It is two chapters later that the reader discovers the company returned its “unused contingencies” to the government.

"The auditor's report showed that upon these contracts the company had profited $182,770.60, and on February 3, 1922, Eastman personally presented a check from the company for this sum to Secretary of War John W. Weeks. Including sundry small refunds, this made a total of $335,389.76, representing war profits which the company returned to the United States Treasury." [See Footnote #2]

This is important information to reveal the motives of George Eastman during World War I: it wasn’t about profits.

|

This lack of order also causes problems to someone unfamiliar with the advances in new photographic technology. It feels rather disjointed. It is difficult to quickly ascertain what-happened-when in the history of film development. Then again, Microsoft Word’s “cut and paste” to reorder text just wasn’t available to editors in 1930, was it?

This is a minor irritation, but it means a researcher must read the whole book before drawing a conclusion about any particular situation. This book is a wonderful and uplifting read. Cheers, - Pete |

Read about Tom Watson and George Eastman and a touching human interest story

|

[Footnote #1] This is not to cast any doubts on the character of those who choose to handle their philanthropy in any specific way. The means by which men such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller Sr., Alfred P. Sloan Jr., Julius Rosenwald, Thomas J. Watson, George Eastman chose to give of their time and money to special causes or their employees is as varied as the individual industrialist. No one way would seem to be the best, but society should keep track of these donations and adjust them appropriately upwards for the times so that history records such practices. How a philanthropy is made isn’t the problem, the problem is man’s short memory.

[Footnote #2] Tom Watson also returned money to the U.S. Treasury headed by Henry Morgenthau Jr. during World War II. The situation was a little different and has not been written up by Peter E. Greulich as of June 21, 2021. In Watson's case, he returned money to the U.S. Treasury after IBM had managed to reduce the costs of production on war bonds. This is documented in Mr. Morgenthau's personal diary. Also, instead of returning the 1 percent profit made during World War II, Tom Watson had the money put into a "Widow's and Orphan's Fund" to take care of the widows and orphans of IBM servicemen who were killed in action. So, although there was a difference in execution between Eastman and Watson, the end result was the same: neither Eastman Kodak's or IBM's bottom lines profited from their World War I and World War II involvements.

[Footnote #2] Tom Watson also returned money to the U.S. Treasury headed by Henry Morgenthau Jr. during World War II. The situation was a little different and has not been written up by Peter E. Greulich as of June 21, 2021. In Watson's case, he returned money to the U.S. Treasury after IBM had managed to reduce the costs of production on war bonds. This is documented in Mr. Morgenthau's personal diary. Also, instead of returning the 1 percent profit made during World War II, Tom Watson had the money put into a "Widow's and Orphan's Fund" to take care of the widows and orphans of IBM servicemen who were killed in action. So, although there was a difference in execution between Eastman and Watson, the end result was the same: neither Eastman Kodak's or IBM's bottom lines profited from their World War I and World War II involvements.