Lou Gerstner wrote, "People truly do what you inspect, not what you expect." … Lest we forget, these "inspection pages" exist because chief executives are "people" too.

Ginni Rometty's Shareholder Value Performance

|

|

Date Published: July 19, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

Questions answered by Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty's key performance indicator #1:

These are excerpts from "THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition."

- What were Ginni Rometty's shareholder returns?

- How did these returns compare with a similar investment in some commonly held, lower-risk index funds?

- Was Rometty’s pay commensurate with her shareholder performance?

These are excerpts from "THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition."

Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty Minimized Shareholder Value

- Past Performance Is a Stakeholder’s Educational Tool

- KPI #1: Minimized Shareholder Value

- Compensation Failed to Correlate with Shareholder Performance

- Behavioral Changes to Consider Before Investing in IBM

Past Performance Is an Investor’s Educational Tool

Just as historians judge the past in the light of the present, we can envision the future out of our knowledge of what has taken place in the past, and what is going on about us now.

Thomas J. Watson Sr., Interview with Merryle Rukeyser

Shareholders all too often are presented in articles as the sole corporate investors, and educating this important stakeholder is the purpose of these articles.

There are, though, four significant investors in a corporation and each of these stakeholders is invested in their own unique way: (1) customers dedicate time, energy, and money to implement products—careers are at stake with the success or failure of these implementations; (2) employees exchange loyalty for paychecks, promotions, and rewarding careers; (3) shareholders invest for a return in both stock appreciation and dividends; and (4) society distributes the tax dollars of all three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the businesses need to optimize profits and operate in peace.

In fact, every individual, as they go through daily life, swaps out the mantles of all these different stakeholder personas. They are a consumer dropping off their children at a local day care; they are a worker assembling a new marketing campaign; they are an investor checking on their 401(k) retirement savings; and they are a member of a society that expects traffic signals—built by corporations and properly positioned by government entities—to keep them and their children safe on the communal roads home after work. All individuals are consumers, workers, and investors; and all corporations are vested in the success or failure of their societies. To say otherwise is ludicrous.

Studying the past performance of a corporation is critical for each these investors—or an individual—to make well-informed short- or long-term investment decisions. These articles focus on the return shareholders have received during a time when shareholder primacy was the battle cry of the corner office at IBM. Shareholders need to understand that they may win short-term battles standing alone, but they rarely—if ever—win the long-term war without the support of their other stakeholders. The Rometty years prove this point.

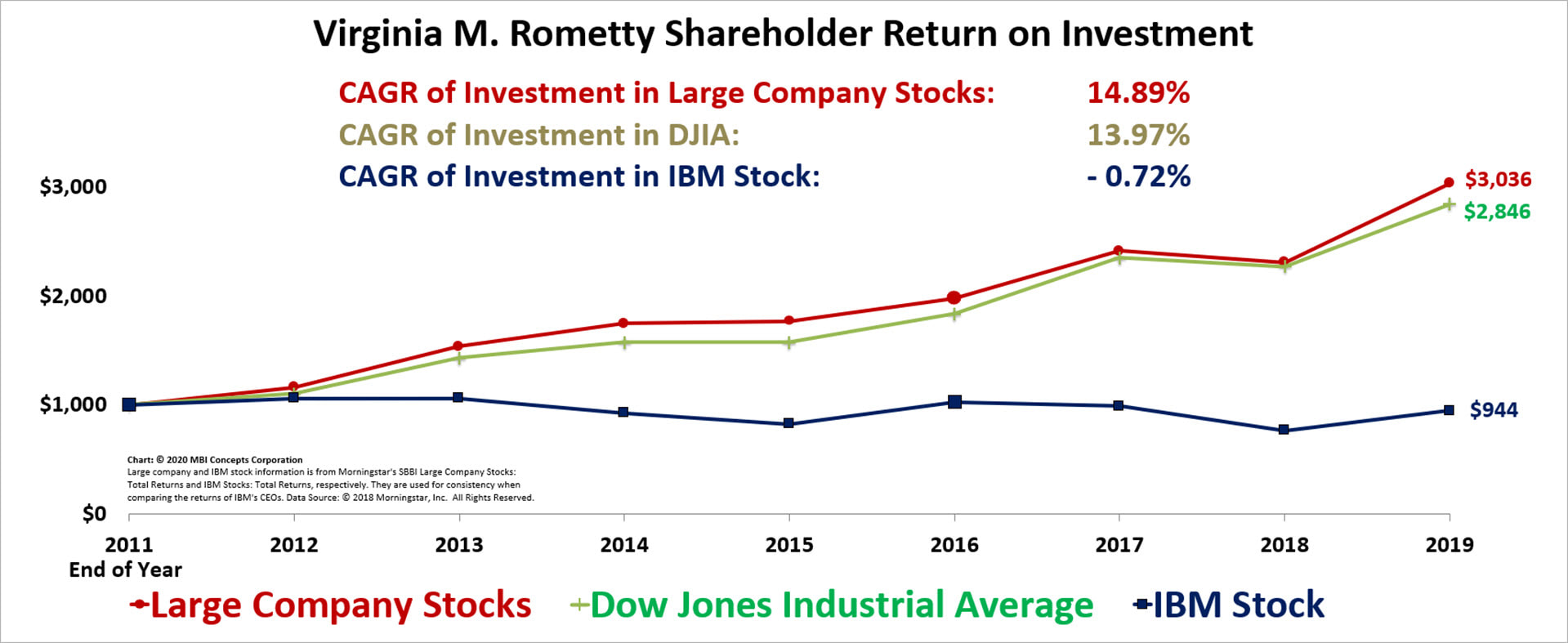

Let’s start with her most obvious and easily documented shareholder failure: The return on an eight-year $1,000 investment compared with the lost opportunity of not investing that $1,000 elsewhere.

There are, though, four significant investors in a corporation and each of these stakeholders is invested in their own unique way: (1) customers dedicate time, energy, and money to implement products—careers are at stake with the success or failure of these implementations; (2) employees exchange loyalty for paychecks, promotions, and rewarding careers; (3) shareholders invest for a return in both stock appreciation and dividends; and (4) society distributes the tax dollars of all three to maintain legal systems, repair and improve infrastructures, and maintain social stability, which the businesses need to optimize profits and operate in peace.

In fact, every individual, as they go through daily life, swaps out the mantles of all these different stakeholder personas. They are a consumer dropping off their children at a local day care; they are a worker assembling a new marketing campaign; they are an investor checking on their 401(k) retirement savings; and they are a member of a society that expects traffic signals—built by corporations and properly positioned by government entities—to keep them and their children safe on the communal roads home after work. All individuals are consumers, workers, and investors; and all corporations are vested in the success or failure of their societies. To say otherwise is ludicrous.

Studying the past performance of a corporation is critical for each these investors—or an individual—to make well-informed short- or long-term investment decisions. These articles focus on the return shareholders have received during a time when shareholder primacy was the battle cry of the corner office at IBM. Shareholders need to understand that they may win short-term battles standing alone, but they rarely—if ever—win the long-term war without the support of their other stakeholders. The Rometty years prove this point.

Let’s start with her most obvious and easily documented shareholder failure: The return on an eight-year $1,000 investment compared with the lost opportunity of not investing that $1,000 elsewhere.

KPI #1: Minimized Shareholder Value

The negative corporate performance in the first chart is not what any competent chief executive would call maximizing shareholder value. Shareholders do not invest $1,000 over eight years expecting to lose $56 while lower-risk mutual funds perform superlatively, returning three times their original investment.

Ginni Rometty’s shareholders consistently lost money over her eight years—including dividends. A competent board of directors should have addressed this poor executive performance, as this corporation’s former board did in 1992 with John F. Akers.

Ginni Rometty’s shareholders consistently lost money over her eight years—including dividends. A competent board of directors should have addressed this poor executive performance, as this corporation’s former board did in 1992 with John F. Akers.

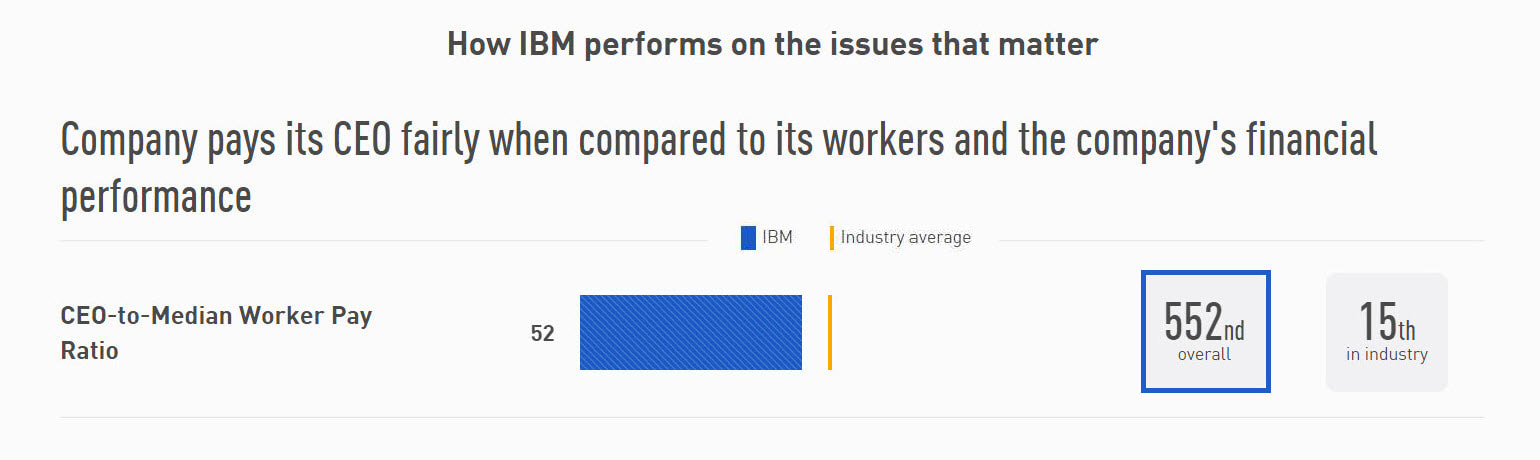

Compensation Failed to Correlate with Shareholder Performance

As much as her shareholders left on the table, Ginni Rometty did not suffer financially or have her employment or job security threatened. The upward climb of her total compensation package stands in stark contrast with all the flat or downward performances documented in this article and the following seven articles. [Footnote #1]

Behavioral Changes to Consider Before Investing in IBM

|

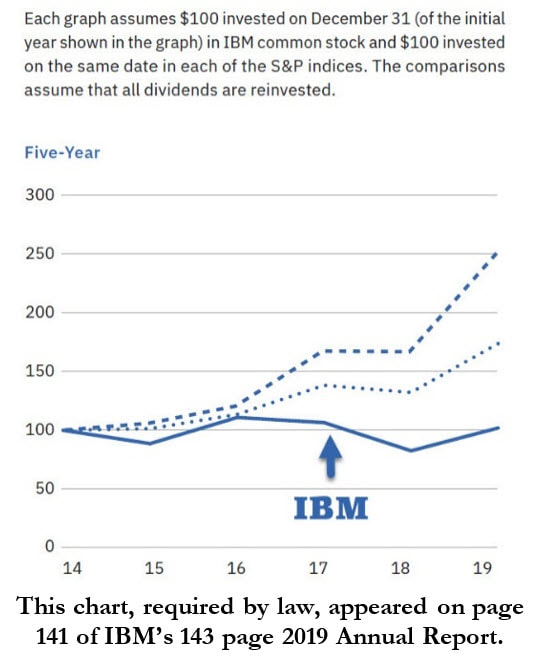

Instead of including the legally required chart to the right which documents a shareholder’s five-year returns on the second-to-last page of the corporation’s annual report, it would be characteristic of a company that promotes trust and transparency, to include this chart in the front matter with the chief executive officer’s opening perspectives—no matter how poor the results.

The IBM Board of Directors should require in every annual report a section on the compensation of the company’s chief executive officer and the top lieutenants. This should be written in clear language and include comparative information similar to JUST Capital’s 2019 analysis below [Rometty’s pay]. |

[Footnote #1] Per IBM’s SEC Schedule 14A, the following is included in Virginia M. Rometty’s compensation: salary, bonus, stock and option awards, non-equity incentive plan compensation, change in retention plan value, change in pension value, nonqualified deferred compensation earnings, personal financial planning, ground transportation, personal security, annual executive physical, family attendance at business-related events, and personal travel on company aircraft. Ginni Rometty’s average pay was $19.8 million. Her lowest and highest earnings years were $14 million and $32 million in 2013 and 2016, respectively.