Review of "The Life of Andrew Carnegie" by Burton J. Hendrick

|

|

Date Published: May 11, 2022

Date Modified: January 1, 2024 |

“In this new biography, Burton J. Hendrick has done more than depict the granddaddy of our modern steel industry. He has depicted that industry, for its creation and its development were so closely locked with that jovial Scot’s own life that neither man nor industry can be considered, save together. When one contemplates the steel industry and its most glorious figure, he finds himself facing the whole modern world which was blown from the Bessemer furnace.

"This is not merely a biography, but an absorbingly told study of an epoch.”

"This is not merely a biography, but an absorbingly told study of an epoch.”

Mark S. Watson, “An Epochal Study of an Epochal Hero,” Baltimore Sun, November 20, 1932

A Review of The Life of Andrew Carnegie by Burton J. Hendrick

- Reviews of the Day: 1932 (During the Great Depression)

- Observations of Andrew Carnegie from The Life of Andrew Carnegie

- This Author’s Thoughts on The Life of Andrew Carnegie

Reviews of the Day: 1932 (During the Great Depression)

|

”This biography portrays Carnegie as an exceptional likeable and human sort of man. It goes to elaborate lengths to present his family background, the details of his private life, his friendships on both sides of the ocean … The biographer, perhaps, is a little too full of uncritical admiration for his subject. … As a sketch of the human side of the man, it is extremely interesting. Carnegie was not austere … and unapproachable. … He was zestful, impish, undignified. He had fun.”

“Scanning New Books,” The Kenosha Evening News, October 22, 1932

“According to Hendrick, it was Carnegie’s imaginative and adventurous plunge in the depression of 1873–75 that made him the multimillionaire he eventually became. When other magnates were retrenching at every step, Carnegie was building great steelworks. Then when the upturn came, he was in the most advantageous position to forge ahead. …

"[Would] … Carnegie utilize the [current] depression of 1929–32 to put thru a program of expansion? … The chances are he would do what other industrial leaders have been doing. … He would pull in his horns with the rest and wait for the storm to spend itself.” |

“Personal Views of the News,” by J. E. Lawrence, The Lincoln Star, October 23, 1932

“Burton J. Hendrick, who has been three times the recipient of the Pulitzer prize for biography, approaches his material with the poise of a scholar and the fascinated attention of a man sensitive to the complexities of the human animal. At his disposal were the vast array of Andrew Carnegie’s private documents. The panoramic treatment of the era and the brilliant analysis of character combined with the enormous amount of new and important material makes ‘The Life of Andrew Carnegie’ one of the notable and significant biographies of the year.”

“Book Reviews on Two Leaders in Industries,” The Chicago Tribune, December 13, 1932

Observations of Andrew Carnegie from The Life of Andrew Carnegie

Volume I: Dunfermline (1835–1848) to Race Imperialism (1890–1908)

B. J. Hendrick on Carnegie’s Character

With the last observation it only seems appropriate to start with this observation from Volume II.

- On Carnegie’s Courage and Faith in Self

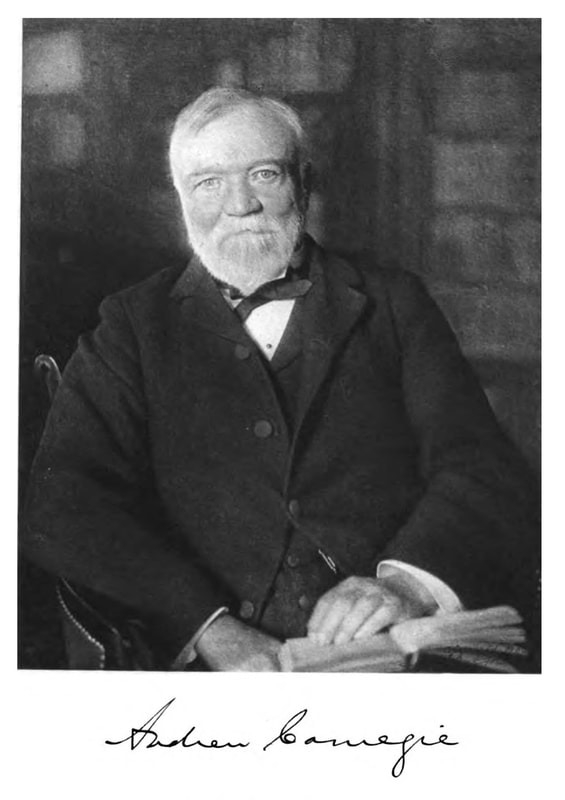

“It will therefore be worthwhile to note any qualities unique in Andrew Carnegie, or any qualities common in other men which he possessed in exceptional degree. … Among these were quickness of decision, assertiveness, absolute confidence in himself, and a willingness to accept responsibility that amounted to little less than audacity. … Carnegie’s self-reliance—a self-reliance so great that unfriendly critics used to regard it as an abnormal egotism—never failed him at any period of his life.

“One of the characters he most abhorred was the speculative business man; his hatred of gambling, in the conventional sense, was a sincere conviction, and only became stronger as time went on, yet Carnegie never hesitated, on critical occasions, to stake his whole future on a single throw.

“More descriptive words for this quality are probably courage and an abiding faith in his star.”

- On Carnegie’s "Ruthlessness

“There was also an inexorable quality in Carnegie—a trait which some described as ‘ruthlessness,’ but which was rather an insistence, in his business relations, on the maintenance of certain principles, and a rigid attention to the duties of time and place. No man ever suffered fools less patiently. It was a general comment, in his days of large affairs, that any man who made a serious mistake did not long survive to repeat the error. … [but] …

"The whole proceeding both the original discipline and the mellower mood that supervened [ensued] – was characteristic.”

- On Carnegie’s Gaining of Wealth

“Carnegie’s papers enables one to trace rather closely his emergence.

“Character and ability rank above other considerations. Mental keenness, rapidity of cerebration, quickness in seeing an opportunity and acting upon it, boundless and irrepressible ambition, insistence that the world accept him at his own valuation, and a personal charm and talent for human association that made others look to him for leadership—these qualities, working in circumstances that offered numerous roads to wealth, had, by 1863, launched Carnegie on his money-making career.

“As the story progresses one fact looms conspicuously: Carnegie was never a hard worker—not a hard worker, that is, in the grindstone sense; he spent at least half his time in play, and let other men pile up his millions for him.

“He was the thinker, the one who supplied ideas, inspiration and driving power, who saw far into the future, not the one who lived laborious days and nights at an office desk.” - On Carnegie’s Pragmatic Nature

“One of Carnegie’s business virtues was the unabashed recognition of fact, no foolish pride ever preventing him from drawing the appropriate conclusion from the established premise.

“No man better knew when to fight, and no one better when to compromise or even to surrender.”

- On Carnegie’s Ability to Choose Men

“He seemed to have an unerring instinct in his choice of men.”

With the last observation it only seems appropriate to start with this observation from Volume II.

Volume II: Growth of Carnegie Domain (1893–1900) to Shadowbrook (1919)

- Carnegie – Alone – Ran His Human “Relations” Organization

“Carnegie similarly carried to perfection his principles of management and organization. They came to full flower about the year 1900. It was this department—the human department—that above all he made his own. All phases of [engineering] technique he highly esteemed and cheerfully left to others, but the humanization of his now enormous enterprise was regarded by Carnegie as his peculiar talent.

“He said, ‘That most complicated of all pieces of machinery, man, has been my province.’ … Carnegie believed profoundly in the average man and took particular delight in discerning ability which the less observant had passed over.”

- Carnegie Invested in the Business During Times of Recession and Depression

“This doctrine of keeping ahead of the times Carnegie proceeded to put in practice to such an extent that, during the hard times from 1893 to 1898, his furnaces and mills were almost completely rebuilt. A mania for destruction seemed to possess the entire organization. Carnegie expressed the purpose somewhat differently: ‘A perfect mill is the way to wealth.’ Tearing down antiquated structures and replacing them with new was a pastime in which he took delight. The surplus which more exigent [pressing] partners begged should be distributed as dividends went into facilities for making steel.

“When proposals [for new facilities] came up for consideration, only one question was asked: ‘Would the projected change improve quality and lower costs?’ On an affirmative answer, wreckers and builders were put to work. ‘Well,’ Carnegie would say each January—at least there is a legend to that effect—‘what shall we throw away this year?’

“The Minutes [Board of Director Minutes] tell an endless story of new installations, the purchase of new properties, the acquisition of new patents.”

- Carnegie’s “Vacations” Produced Historic Results for the United States of America

“This epoch witnessed Carnegie’s greatest independent contribution to the industry in the United States. The adoption of the basic open-hearth process in this country was his achievement. … It is true that he [Carnegie] was not a pioneer, that he contentedly let others do the experimental work and then, after success became assured, would take up the innovation and develop it on a scale that astonished, almost frightened, more timid souls. In the mechanism which forms the groundwork of the American steel trade today, however, Carnegie was the trail-blazer.

"It is important also that the introduction of the basic process was a by-product of one of those summer vacations which sometimes caused grumbling among his desk-bound partners. The episode furnishes a splendid justification of Carnegie’s theory that the master of industry gets the most desirable results when his imagination is stimulated by miscellaneous associations with his fellow men.

“Untraveled competitors regarded these [Carnegie] European trips merely as pleasure and had much to say of Carnegie’s neglect of business and his willingness to let others sow that he might reap. But in a great business, ideas are more important than office routine; and ideas, picked up perhaps at a dinner table, perhaps in chance conversation on a boat or railway train, perhaps from meeting statesmen or scientists, or a tour of foreign plants, were what counted.

“The adoption of the basic [open-hearth] process illustrates the method at its best. … [and] … The outcome of this proceeding was that the first basic open-hearth furnace in the United States was installed at Homestead, in March,1888.”

- Carnegie vs. J. P. Morgan in the Steel Industry

“The reason Carnegie felt no sense of danger is apparent. Braddock, Homestead and Duquesne [Carnegie steel plants] represented the finest accomplishments of engineers. When placed side by side with the creaky mills that J. P. Morgan had assembled, several of which dated from the Civil War, they shone to particular advantage.

"The Carnegie Company had no watered stock on which dividends must be earned; there was no anxious public watching its ups and downs on the Exchange, and no bankers in the background insisting that dividends be paid. Should the Carnegie Company start making tubes and fail, its loss would be its own affair, merely a passing misfortune, to be recouped in other fields; should the National Tube [J. P. Morgan’s business] meet adversity, its securities tumbling in a mighty crash, would involve thousands in ruin, and injure, perhaps seriously, the banking firm that had sponsored them. … [J. P. Morgan’s trust’s] strength was its monopoly; it was the only bulwark, and this was a fragile reed when a band like the Carnegie Company was in the field. …

“Carnegie’s strength and Morgan’s weakness were pointed out in the report on the United States Steel Corporation made by the Stanley Committee in 1912: ‘It was a contest between fabricators of steel and fabricators of securities; between makers of billets and makers of bonds.’ ”

This biography was released only a few months before the trough of the Great Depression. The country desperately needed a way forward. It was a time when anarchists and fascists were challenging the country’s economic system. This book held up a light: It was the industrialists, not the capitalists, who practiced business-first philosophies that had previously—and could now—carry the country through desperate times. Speculation on Wall Street had contributed to the current depression and many past recessions, and Andrew Carnegie’s life story was an amazing light on the path forward. Tom Watson Sr. followed his example: (1) have faith in your country, its businesses and its workers, (2) invest in your company during down times when prices are depressed, and (3) prepare to drive aggressively forward with the economy’s upturn.

During the Great Depression, Watson Sr. followed Carnegie’s example and stored his corporation’s “overproduction” in the company’s factories; he kept his top, trained employees working; he invested aggressively in factories, laboratories, and research and development; and then when the economy turned up, the chief executive officer and his corporation were ready to expand and take market share. This book offers an amazing example of Carnegie’s corporation as one of Emerson’s lengthened shadows—an institution as the lengthened shadow of one man. It is an amazing history lesson in how a single individual can affect the course of his company’s and his country’s economic history.

Andrew Carnegie and Thomas J. Watson Sr. both practiced business-first: They invested in making their people more productive, their processes more effective, and their products more valuable. [See Footnote]

America is what it is because these men believed in business-first philosophies.

During the Great Depression, Watson Sr. followed Carnegie’s example and stored his corporation’s “overproduction” in the company’s factories; he kept his top, trained employees working; he invested aggressively in factories, laboratories, and research and development; and then when the economy turned up, the chief executive officer and his corporation were ready to expand and take market share. This book offers an amazing example of Carnegie’s corporation as one of Emerson’s lengthened shadows—an institution as the lengthened shadow of one man. It is an amazing history lesson in how a single individual can affect the course of his company’s and his country’s economic history.

Andrew Carnegie and Thomas J. Watson Sr. both practiced business-first: They invested in making their people more productive, their processes more effective, and their products more valuable. [See Footnote]

America is what it is because these men believed in business-first philosophies.

This Author’s Thoughts on The Life of Andrew Carnegie

B. J. Hendrick’s The Life of Andrew Carnegie is a masterpiece. The entire manuscript is to be recommended but, as usual, I will highlight several chapters that are, in this case, the best-of-the-best: (1) Volume I: “The Dawn of Bessemer Steel,” “The Disgrace of Dying Rich,” “Prologue to Homestead,” and “The Homestead Strike;” (2) Volume II: “The Sale to Morgan” and “For the Improvement of Mankind.”

- This work is an American industrialist’s biography intertwined with mini-biographies and mini-narratives about those who helped shape iron into steel in the United States of America: Andrew Carnegie and Henry Bessemer and the introduction of Bessemer Steel to America, Andrew Carnegie and Henry C. Frick and the notoriously remembered Homestead Strike, Andrew Carnegie and Charles Schwab and the growth of the Carnegie Company, Andrew Carnegie and J. P. Morgan and the founding of the U. S. Steel Corporation … The common denominator always being, appropriately, Andrew Carnegie. He pushed and pulled others forward with the philosophy he put into practice later in his life: “Put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket.”

- This work documents how one man gave the United States of America an edge in the production of a critical resource that gave rise to its worldwide dominance and ability to be a positive force during World War I.

- This work describes the personal growth of an industrialist into a philanthropist, the evolution of iron into the strongest of steels, and, following the Civil War, the expansion of our country through the ever-onward push of the railroads that knit together our vast republic. The book is filled with a depth of facts that the author delivers in an exquisite and expansive manner—it is prose that, at times, reaches into the realm of poetry.

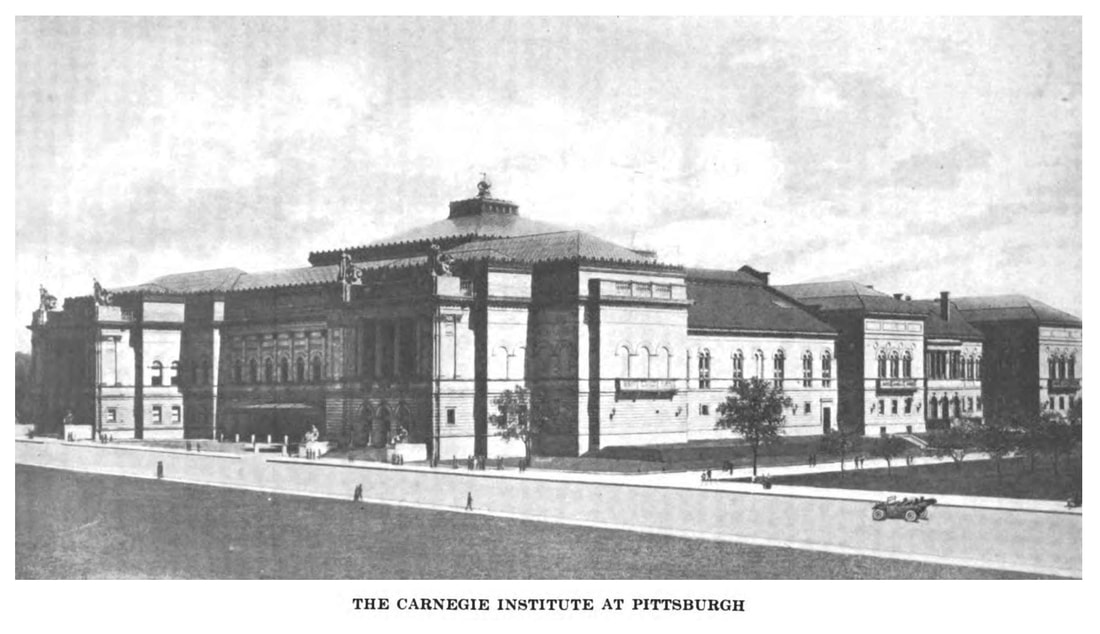

- Lastly, this is a work that paints the picture of an industrialist who desperately wanted men to live together in peace and performed not just good works but great works for his fellow man: both during his lifetime and after his death.

Regarding this last point, I will close with B. J. Hendrick’s insight into how Carnegie’s philanthropy reached beyond anything that anyone of wealth had done up to this time.

|

“The extent to which other men and women of wealth—Rockefeller, Harkness, Rosenwald and the like—have followed his example of establishing great money-giving funds with no ‘dead hand’ attached, shows that ‘philanthropy’ has been placed on a new footing. These foundations, twenty of which disburse not far from fifty million dollars a year, the two largest being the Carnegie Corporation with resources of $160,000,000, and the Rockefeller Foundation with $147,000,000, have really become a new estate in the American realm.

|

“Carnegie’s original purpose, of showing men of vast wealth how to fulfill a useful purpose and help balance the necessary inequalities of the existing economic system, may be regarded as achieved. … Millionaires who today die possessed of great surpluses undedicated to public ends, die ‘disgraced’ indeed.

“To have engendered this new morale in men of his own kind, to have caused literally billions of dollars that, in the old day, would have rested in private hands, to flow in channels that promote the well-being of the common man and add to the amenities of his existence – this was Carnegie’s lasting achievement.”

“To have engendered this new morale in men of his own kind, to have caused literally billions of dollars that, in the old day, would have rested in private hands, to flow in channels that promote the well-being of the common man and add to the amenities of his existence – this was Carnegie’s lasting achievement.”

[Footnote]: Tom Watson did learn the hard way. During the Great Depression, he said that he “was ashamed” of his mistake during the Recession of 1920–21. . . . But he didn’t make the same mistake twice.