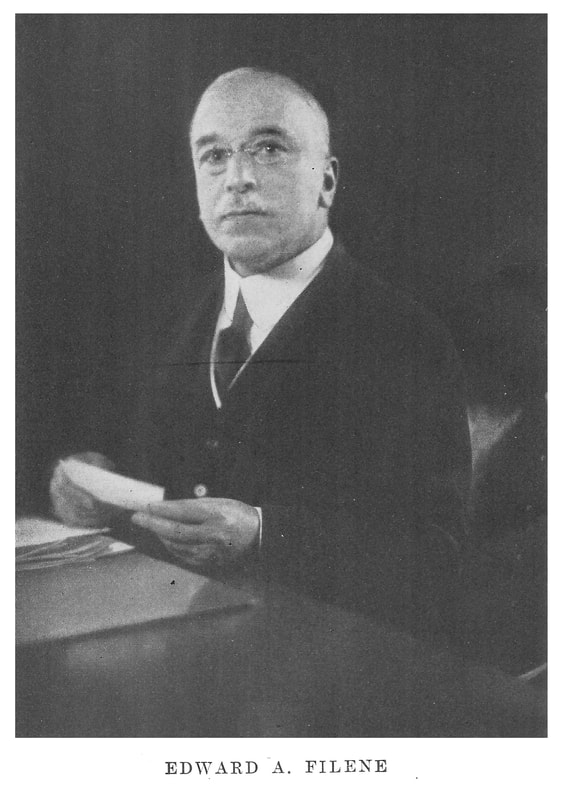

Edward Filene: Six Keys to Success

|

|

Date Published: September 1, 2021

Date Modified: March 3, 2024 |

If this article wasn't dated, a reader would be hard pressed to believe it was written at the beginning of the 20th Century rather than the 21st Century. Images have been added to make this 100-year-old article "feel" more current. Maybe the images will help overcome some pre-conceived notions.

I agree with Edward A. Filene when he writes, "Genius is an infinite capacity for hard work.”

I agree with Edward A. Filene when he writes, "Genius is an infinite capacity for hard work.”

Peter E. Greulich, Author and Public Speaker

The Rules of Success

- Make Your Plan in Writing

- Compare It with the Methods of the Most Successful Men [and Women]

- Have Those It Will Affect Criticize It in Advance

- Put It into Operation

- Keep It in Operation until Rescinded

- Allow Revision, But Only After the Most Careful Reasoning

The Rules of Success: Applying Ideas Successfully

|

This article is from Volume II

|

Is success … a matter of rules?

We are apt to think of success as something entirely compounded from genius, and not a few successful people are very fond of declaring—although not in so many words—that, to all intents and purposes, they have been touched with a magic wand. I am inclined to accept the definition of genius as “an infinite capacity for hard work.” |

|

And out of my own experience, I know that success is usually as much the result of inspiration as the result of coordination and careful planning, and thus, I think that there are rules for success. …

What I mean by the “rules of success” can be more concretely, although more clumsily, stated as the rules of the successful application of ideas. Success is founded upon ideas—they are the bricks. The rules furnish the mortar. You cannot build a house with bricks alone, nor with mortar alone. The two are complementary. An idea, to be useful, has to be communicated. There are then certain rules for guidance in developing ideas which I and others have found successful, and so, I think, they may be considered as of general application. |

Here they are:

1. Make Your Plan in Writing

|

Until the plan is reduced to writing, it cannot be considered a plan at all.

An ingrowing thought is not an idea—it is more in the nature of what is called a “hunch.” It may interest and amuse its possessor, but it is of no earthly use unless communicated. If you cannot put your idea or your plan down on a sheet of paper, most certainly you cannot transfer it to the mind of another. It is extraordinary, when applying this principle, how very many of what we consider ideas turn out to be nothing at all. For, when reduced to black and white, the point that we thought we had and thought to be only elusive—is not there. We had merely been having a dream.

|

Only the technology underlying the "writing down" has changed.

|

And, as Stevenson [Robert Louis Stevenson] points out in one of his essays, he evolved a great number of perfectly splendid plots in dreams, but whenever he put them into writing the climax vanished.

2. Compare It with the Methods of the Most Successful Men [and Women]

|

The immature idea is that one should evolve a plan or an idea from what might be called the totality of originality—from A to Z, and that there is something wrong about borrowing ideas and parts of ideas, or in taking anything that has gone before.

Exactly the contrary is true. No one, in his lifetime, can possibly cover the entire ground of a subject. The man who gets on is the man who gathers, in the least possible time, the greatest amount of information from the labors of others. The questions to ask ourselves – when we are putting the idea into writing – when we are forming a new plan, are: |

"Mature ideas" consider past experiences

|

“Has anyone else done this?” and “Have they done it better than I plan to do it?” If we find that it has been done, we may or may not find that our way … is the best way. But, undoubtedly somewhere, we shall discover that someone else has had at least a part of our idea and has something which we well might build upon.

A really big idea, a really big plan, a really great success, is always based on a collection of what has gone before and is not something wholly new and original. For instance, if we are retail merchants, the best course in the world is to circulate among the largest possible number of retail stores—find out what they are doing. If we cannot discover improvements upon our own idea, it is simply because we are blind.

No plan is ever perfect; our idea is always open to change and amendment; it can always be improved; and the best and easiest way to discover this improvement is to see what the other man is doing.

A really big idea, a really big plan, a really great success, is always based on a collection of what has gone before and is not something wholly new and original. For instance, if we are retail merchants, the best course in the world is to circulate among the largest possible number of retail stores—find out what they are doing. If we cannot discover improvements upon our own idea, it is simply because we are blind.

No plan is ever perfect; our idea is always open to change and amendment; it can always be improved; and the best and easiest way to discover this improvement is to see what the other man is doing.

3. Have Those It Will Affect Criticize It in Advance

|

Our plans are bound to be criticized either before or after they are put into operation. This is to me the most important of all the rules, and for two reasons:

The first is that we must work with men and, therefore, before we put anything at risk, we should know the reaction of the people affected. I could give any number of good ideas that have proved utterly unworkable simply because they were not offered for criticism before being put into operation.

The second reason … is that criticism to most people connotes destructive comment. Constructive criticism is almost unknown and when it does occur, is usually taken for praise. Destructive criticism may or may not be helpful.

|

An open communication about the plan "before implementation" is critical

|

It may be very helpful indeed in the way of showing up really weak spots which may be changed, or it may be helpful in discovering sections of adverse sentiment which have to be treated before the plan can get a fair trial. And this opportunity for confidential advance inspection gives the opportunity to make slight and even unnecessary changes to suit particular factions, and it will usually happen that those who might easily have continued against the idea will turn into the liveliest of proponents.

4. Put It into Operation

|

It is self-evident that after a plan has been approved, it should be put into operation and that would seem to be a mere mechanical detail.

On the contrary, here is a point where killing opposition may again be met. For example, we have all seen street railway companies evolve perfectly good plans for handling traffic and then put them into operation in such an ingeniously stupid way as to almost cause a riot. To explain what I mean perhaps it would be better to substitute for the phrase “put into operation” the phrase “slide into operation” with the emphasis on slide—which means in turn that every explanation and direction should be forthcoming in order that the possibility of a slip up may be reduced to the absolute minimum.

|

"Slide" the change into operation

|

Unless those affected understand what is expected of them, the new idea of a supposed improvement may only serve to cause confusion.

5. Keep It in Operation until Rescinded

|

Until our plan keeps in operation automatically, we have not organized it.

The difficulties a plan is likely to meet when put into operation should be foreseen and provided for. After the first enthusiasm—always associated with the starting of a new thing, there comes a sort of reactionary lull—when a fresh impetus is needed; and if that impetus is not at hand, the idea will fail simply through inaction. The father of the idea cannot afford to push his idea like an empty boat into midstream to let chance take it where it may. He must follow it for a time and that time is regulated by circumstances.

|

The plan must become "automatic"

|

A plan which we believe is good should be kept going by its author either until it has proved itself to the point of becoming automatic or to the point of being discarded, for unless a plan ... becomes automatic, there is some radical defect which means either a discarding or a drastic revamping.

6. Allow Revision, But Only After the Most Careful Reasoning

|

Once a plan has proved itself in operation, that is, has become automatic, improvements will undoubtedly … be suggested.

If there is any idea in mind that the thing is perfect and cannot be improved under any circumstances, then eventually it will fail, because it will cease to meet the inevitable changes which occur with conditions. Nothing is static. More people and more concerns fail because they will not adjust themselves to conditions than for any other reason. But, on the other hand, too ready a willingness to meet purely transient conditions breaks down the backbone of an idea and leaves it flat and wobbly.

|

Do not lock your plan "in stone"

|

If we treat a change suggested in any plan which is in operation as a new idea and subject it to the kind of scrutiny I have outlined in the previous paragraphs, we shall not too easily change, but at the same time, we shall not permit our schemes to become wooden.

Edward A. Filene, "The Rules of Success," The Book of Business, 1920