An IBM Financial Engineering First

John R. Opel's Revenue Strategy of the 1980s

|

|

Date Published: August 9, 2021

Date Modified: June 29, 2024 |

This rental/lease purchase conversion was the first time an IBM chief executive officer attempted financial engineering— following a short-term, financially expedient path at the expense of the long-term health of the business.

It eventually led to the Financial Crisis of 1992-93.

It eventually led to the Financial Crisis of 1992-93.

Peter E. Greulich, "THINK Again: The Rometty Edition"

IBM's First Attempt at Financial Engineering: A Rental/Lease to Purchase Conversion

To establish perspective, IBM had been here once before. In the early years of Tom Watson Jr.'s leadership a consent decree required IBM to offer both rental/lease and purchase options to its customers. Many existing customers at the time opted to purchase their hardware. This spiked IBM's revenue and profits. Tom Watson thought it was a temporary spike.

Here is how a great chief executive positioned what be believed was a temporary spike in revenues and profits.

Here is how a great chief executive positioned what be believed was a temporary spike in revenues and profits.

Thomas J. Watson Jr.'s Thoughts on Rental vs. Purchase

|

“The substantial rise in IBM’s net earnings during the first quarter of this year, compared to the first quarter of 1960, is apt to be misleading unless stockholders completely understand the reason for the increase. While the first quarter report contained a statement explaining the reason, I want to go over it with you again because it is important that you understand what is taking place.

“I’m sure you all know that IBM’ business comes primarily from the rental of data processing equipment and this continued to be so in the first quarter of this year. However, during the first quarter, outright sales of data processing equipment were substantially higher than they were in the first three months of last year. “Of the total machines we shipped and billed to customers during the first quarter of last year, approximately 7% were sold outright and 93% were rented. In the first quarter of this year, however, 31% were sold outright, and 69% were rented. Now, of course, when you make an outright sale of equipment, it has the effect of causing income to be realized immediately. For that reason, outright sales have the effect of increasing current earnings and decreasing future earnings.

|

This information is from the IBM 1961 Shareholders Annual Meeting

|

“It is obvious from what I have just said that the higher proportion of outright sales—compared to rentals—in the first quarter of 1961 does not represent an, accelerated long-term growth rate for the corporation. In fact, if this high proportion of sales continues, it will tend to inhibit IBM’s future rate of growth.

“This is so because we would he getting profits all at once that we would otherwise be realizing gradually over future months and years [all emphasis added]."

“This is so because we would he getting profits all at once that we would otherwise be realizing gradually over future months and years [all emphasis added]."

Unfortunately, where Tom Watson saw problems, John Opel saw an opportunity: financial engineering.

Financial Engineering: The Effects of the Lease to Purchase Conversion

On February 18, 1985, the cover story of BusinessWeek carried the title “IBM: More Worlds to Conquer.” Inside the magazine, the outgoing chief executive officer, John R. Opel, forecast that IBM would grow its revenue from $49.5 billion to $180 billion by 1994 [most IBMers remember the "$100 Billion IBM by 1990"].

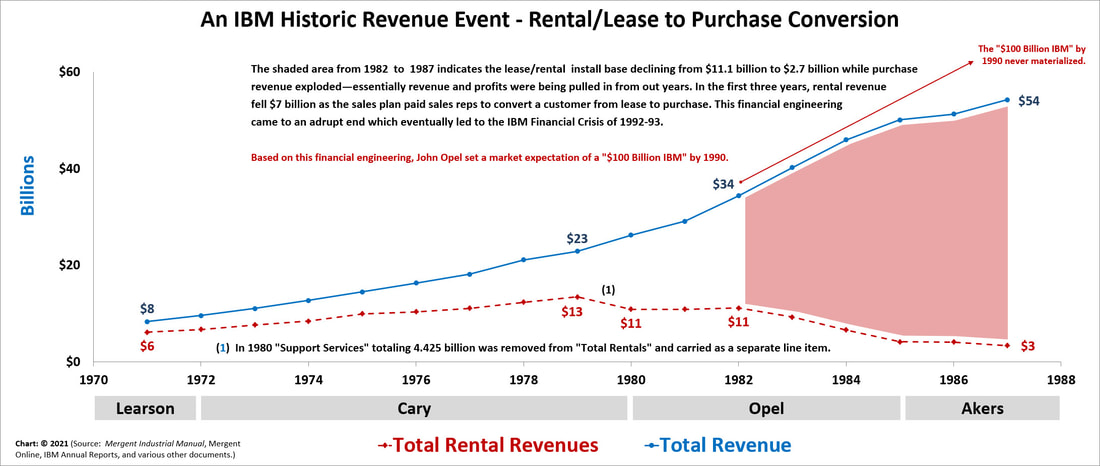

The article’s author wrote about hubris, and hubris it was, as IBM’s first round of bad leadership led the corporation to the edge of a financial cliff. To forecast such amazing growth and to justify the astronomical investments in infrastructure, revenue numbers were financially engineered: IBM sold off its rental hardware base—on the cheap—to drive the perception of organically growing revenues [See Introductory Chart]. It was a shortsighted plan for which it was easy to forecast an end.

That end came in 1985 and it was John F. Akers who took the heat.

The article’s author wrote about hubris, and hubris it was, as IBM’s first round of bad leadership led the corporation to the edge of a financial cliff. To forecast such amazing growth and to justify the astronomical investments in infrastructure, revenue numbers were financially engineered: IBM sold off its rental hardware base—on the cheap—to drive the perception of organically growing revenues [See Introductory Chart]. It was a shortsighted plan for which it was easy to forecast an end.

That end came in 1985 and it was John F. Akers who took the heat.

|

As the BusinessWeek article rolled off the presses, John Akers became IBM’s chief executive officer. In June, only four months later and only five minutes into a speech with Wall Street analysts, he told them, “Achieving the solid growth we expected for 1985 is now unlikely.” Obviously, to go in a single quarter from a corporation setting its sights on $180 billion to one that can’t meet its most recent growth forecasts caused a stir.

David E. Sanger, a business reporter for The New York Times, wrote, “Two wire-service reporters quietly slipped out of the room, breaking into a run once they were out of earshot. |

IBM's stock plummeted taking the entire stock market with it.

|

A half-hour later … IBM’s stock had started to plummet. By day’s end it was down five points, taking the entire stock market with it … the next day the market dropped another 16 points.”

It was a tough day for John Akers when he announced that IBM could not meet the market’s expectations set by his predecessor. It was an even tougher decade for IBM’s shareholders, as they saw IBM’s market value decline from $95.7 billion in 1985 to $28.8 billion in 1992.

Its market value did not fully recover until 1997 [IBM Historic Market Values].

It was a tough day for John Akers when he announced that IBM could not meet the market’s expectations set by his predecessor. It was an even tougher decade for IBM’s shareholders, as they saw IBM’s market value decline from $95.7 billion in 1985 to $28.8 billion in 1992.

Its market value did not fully recover until 1997 [IBM Historic Market Values].

Thoughts on this Information from the IBM 1961 Shareholders' Meeting

And now you know more than Louis V. Gerstner did when he took over IBM. He asked the following question in his book, Who Says Elephants Can't Dance:

I also came away with an understanding that these were enormously talented people, a team as deeply committed and competent as I had ever seen in any organization. I reached this conclusion repeatedly over the next few months. On the flight home I asked myself: "How could such truly talented people allow themselves to get into such a morass?"

|

A CEO shouldn't settle for less than the answers to: Who? Where? How? What? When?

|

Lou Gerstner left the question unanswered. He should have understood IBM history, its people, and its culture a little better.

John Opel caused, with the lease/rental to purchase conversion, income to be realized immediately which increased current earnings and decreased future earnings. Unlike Watson Jr., he sold it as an "accelerated long-term growth rate for the corporation" by talking about the $100 billion IBM by 1990 and the $180 billion IBM by 1994. Unfortunately, it was not an accelerated long-term growth rate but IBM's first attempt at financial engineering. |

This is all IBM history: the good, the bad, and, sometimes, the truly ugly.

IBM wasn't and isn't immune from bad leadership.

We can all learn from it.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

IBM wasn't and isn't immune from bad leadership.

We can all learn from it.

Cheers,

- Peter E.