A Review of A. Scott Berg's Biography: Lindbergh.

|

|

Date Published: March 1, 2024

|

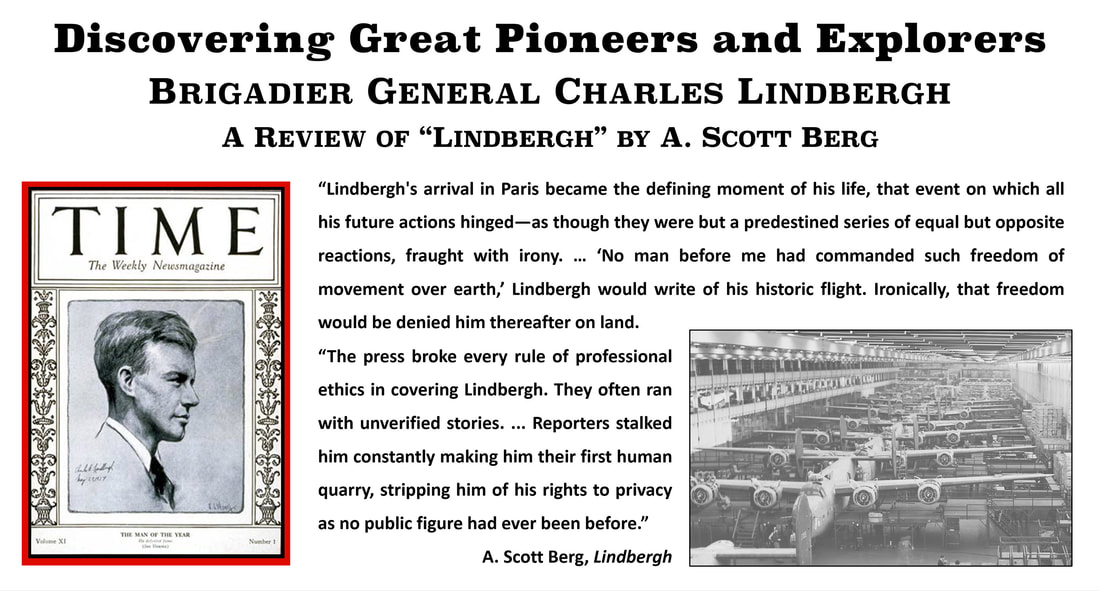

“Recognizing the seriousness with which Lindbergh was taking his new governmental work [with the U.S. military], the mainstream press gave him some elbow room in which to perform his duties. TIME even wrote a piece sympathetic to his side in his ‘long dark years of war’ with the public and the press.

“ ’ For twelve years Charles Lindbergh has been a hero, and twelve years is too much. ... For the fact is that the relation of Charles Lindbergh to the U. S. people is a tragic failure chalked up against the institution of hero worship. ... Either the pursuit of the public will drive him to lead an almost monastic life, abandoning the world which other men enjoy, or perhaps now at last hero worship will die a natural death.’

“Eating its cake and having it too, TIME put his picture on their cover [June 19, 1939].”

“ ’ For twelve years Charles Lindbergh has been a hero, and twelve years is too much. ... For the fact is that the relation of Charles Lindbergh to the U. S. people is a tragic failure chalked up against the institution of hero worship. ... Either the pursuit of the public will drive him to lead an almost monastic life, abandoning the world which other men enjoy, or perhaps now at last hero worship will die a natural death.’

“Eating its cake and having it too, TIME put his picture on their cover [June 19, 1939].”

A. Scott Berg citing “TIME: Heroes: Press vs. Lindbergh,”

A Review of “Lindbergh” by A. Scott Berg

- Reviews of the Day: 1998–99

- Selected, Composite Insights from “Lindbergh”

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

Reviews of the Day: 1998–99

“Although Lindbergh showed to the world his country’s best self, he also aroused within America many of its ugliest aspects. In illuminating this phenomenon, Berg’s book is an extraordinary achievement. … Berg concentrates on the most sensational and controversial features of Lindbergh’s life—the kidnapping of his first child and his career as an ‘isolationist’ during the most important foreign policy debate in American history. …

|

“Berg, who is Jewish, revealed in a recent interview that when he told his grandmother that he was at work on a Lindbergh biography, her reaction was, ‘What do you want to write about him for? He was quite awful about the Jews.’ Luckily for his readers, Berg didn’t listen to his grandmother. … He is the only writer who has been allowed to survey Lindbergh’s complete papers (all 2,000 boxes of them).

“Berg, a scrupulously fair biographer, notes that ‘Lindbergh had bent over backward to be kind about the Jews, but in suggesting that American Jews were other people and that their interests were not American, he implied exclusion. … Lindbergh’s argument was that many Jews who agitated for American intervention did so not out of their sense as Americans—of what was in the national interest, but rather out of their sense as Jews—of what was best for the Jewish people. … Lindbergh’s position was hardly different from that of critics of American Cold War policy who argued that say, Polish or Lithuanian or Cuban Americans who called for the U.S. to pursue confrontational and potentially dangerous policies toward the Soviet Union were pursuing the interests of their ethnic group without considering the interests of their country—and those critics weren’t accused of ethnic hatred. |

Front dust cover of “Lindbergh” by A. Scott Berg in 1998-1999.

|

“However much Lindbergh may have dishonored himself and his cause with his Des Moines speech, after Pearl Harbor Lindbergh strenuously and courageously contributed to the war effort [in spite of the Roosevelt administration].”

Larry Williams, “Exploring the Spirit of Lindbergh,” The Hartford Courant, 1998

”Like its subject, ‘Lindbergh’ offers much to be admired, only to be marred by one jarring, unforgivable flaw. Lindbergh’s flaw was anti-Semitism (and racism) during his leadership of the isolationist movement before World War II. The book’s flaw is trying to sanitize that aspect of the man. …

“Reeve Lindbergh [Charles Lindbergh’s youngest child and author of “Under a Wing”] said she does not believe her father was anti-Semitic. ‘I knew he was not a hater.’ She’s probably right, but his words prove he subscribed to stereotypes. …

“After the war, Lindbergh became an ardent conservationist and lived for a time with primitive tribes in the Philippines whose land was threatened by ‘progress.’

“If he was a racist, it seems like he got over it.”

“After the war, Lindbergh became an ardent conservationist and lived for a time with primitive tribes in the Philippines whose land was threatened by ‘progress.’

“If he was a racist, it seems like he got over it.”

Benjamin Schwarz, “The Right Stuff,” The Los Angeles Times, 1998

Selected Insights from "Lindbergh" by A. Scott Berg

- On Charles Lindberg’s Credibility after President Truman Took Charge During World War II

|

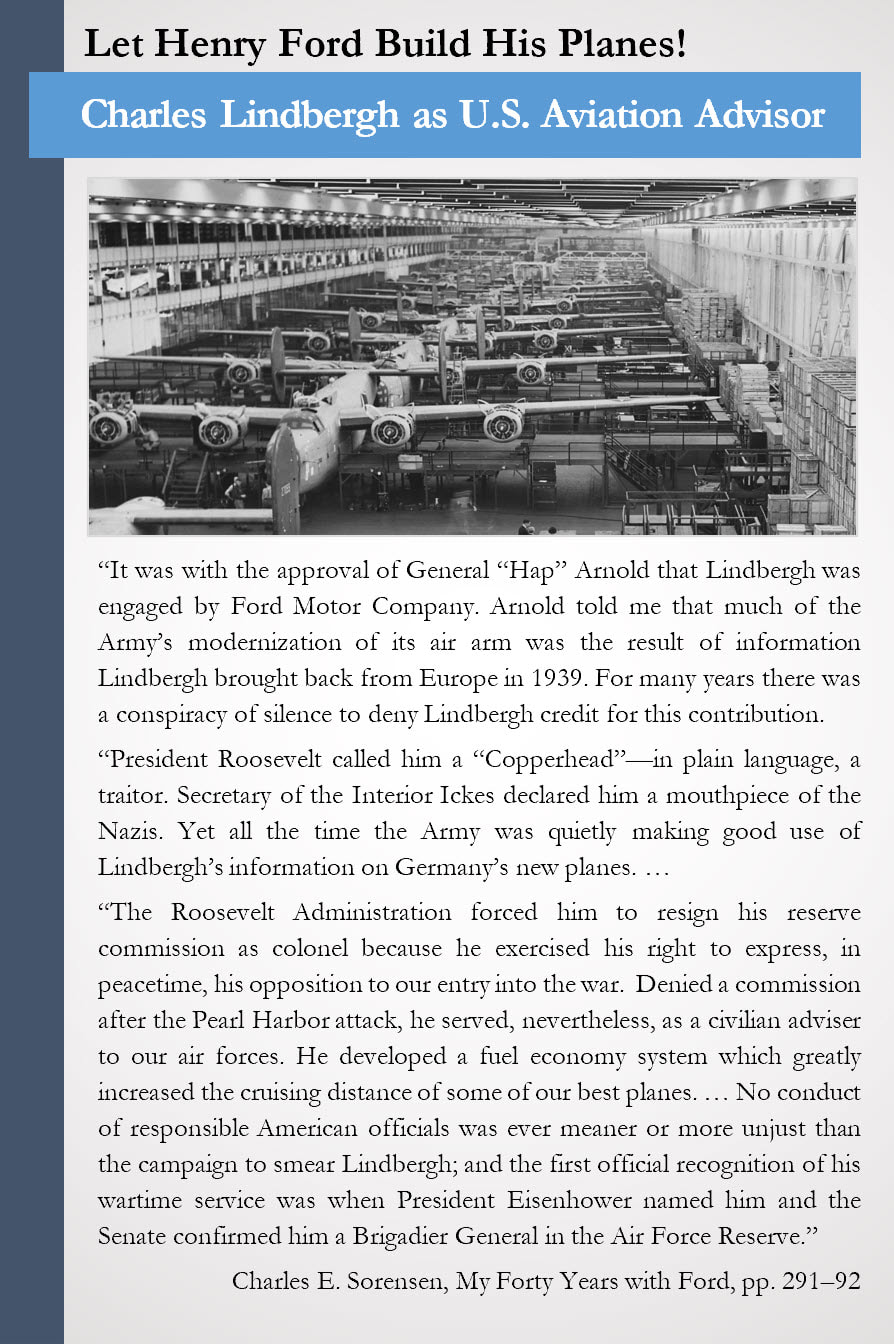

“The passing of Franklin Roosevelt [and inauguration of President Truman] did not affect Washington’s official attitude toward Lindbergh overnight. It took a week. While Allied forces surrounded Berlin, Lindbergh was called to the capital to discuss his joining a Naval Technical Mission expedition to Europe. …

"The nature of this mission was far more sensitive than Lindbergh’s recent military venture and required State Department clearances, authorization he felt he would have theretofore been denied.” - Biggest Understatements Captured by Scott Berg Evangeline wrote her son [about his Spirit of the St. Louis flight]:

|

President Eisenhower recognized Charles Lindbergh for his World War II activities.

|

- Making Enemies of Those Who Eventually Controlled the Lindbergh Narrative in the Press

“William Randolph Hearst wanted to star Lindbergh in a motion picture about aviation opposite his [Hearst's] mistress, Marion Davies. Hearst offered Lindbergh $500,000 plus ten percent of the gross receipts.

|

Marion Davies

|

"Those extra points in the film would probably have been worth at least as much as his salary—leaving him financially set for life. … ‘I wish I could do it if it would please you,’ Lindbergh demurred, ‘but I cannot, because I said I would not go into pictures.’

“What Lindbergh did not say—until many years later in a book of memoirs—was that he objected to Hearst himself. The mogul, Lindbergh noted: 'Controlled a chain of newspapers from New York to California that represented values far apart from mine. They seemed to be overly sensational, inexcusably inaccurate, and excessively occupied with the troubles and vices of mankind. 'I disliked most of the men I had met who represented him, and I did not want to become associated with the organization he had built.’ |

“[But Hearst kept pressuring the then very-young Charles Lindbergh finally saying] ‘if you don't want to make a picture, tear it up and throw it away.’ Double-dared, Lindbergh tore the pages in half and tossed them into the fireplace. Hearst watched with what Lindbergh would long remember as ‘amused astonishment.’ …

“[Later when Lindberg's first child was born] Lindbergh barred five newspapers, including Hearst’s, because of their ‘contemptible journalistic practices.’ … he called upon a policeman to eject one reporter before proceeding. … [As a result] for the first time since he had become famous, Lindbergh received negative press. The masses still worshipped him. … but now many members of the press who felt they had helped create this hero felt unfairly dismissed by him.”

“[Later when Lindberg's first child was born] Lindbergh barred five newspapers, including Hearst’s, because of their ‘contemptible journalistic practices.’ … he called upon a policeman to eject one reporter before proceeding. … [As a result] for the first time since he had become famous, Lindbergh received negative press. The masses still worshipped him. … but now many members of the press who felt they had helped create this hero felt unfairly dismissed by him.”

This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions of "Lindbergh" by A. Scott Berg

- Understanding the Man—Charles Lindbergh and His Hatred of the Effects of War

I have spent the day at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. I have also stood in Auschwitz near Krakow, and Terezin outside of Prague. Visiting Auschwitz and Terezin changed my outlook on life and humanity to a degree that no written words, pictures, or films could ever accomplish. Too few have stood in these actual places of terror and horror, and everyone should. Lindbergh saw such camps first hand as the war ended. He, like I, knew these places existed but what Lindbergh wrote in his diary expressed how I felt after my overseas visits:

|

“It is one thing to have the intellectual knowledge, even to look at photographs [or films] someone else has taken, and quite another to stand on the scene yourself, seeing, hearing, feeling with your own senses.”

Several dictators provided reasons for supporting America’s entry into World War II. If there is any fault to be seen in Charles Lindberg, it was his delay to acknowledge this fact and his failure after the war to openly condemn the atrocities that had occurred. Most of which only became truly self-evident to him as he stood in its midst.

|

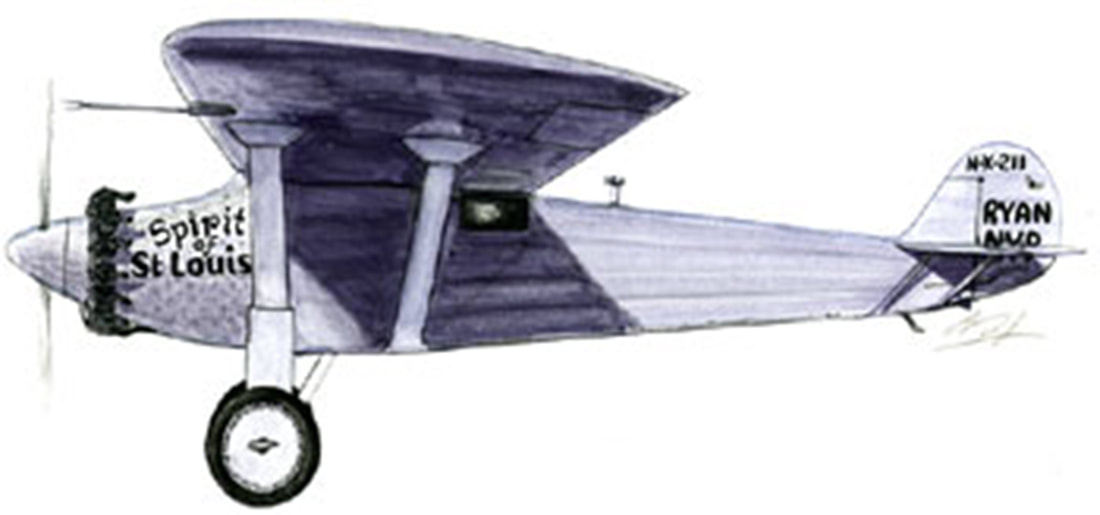

An artist's rendering of "The Spirit of St. Louis."

|

I will not pass judgement on Charles Lindbergh’s full view on humanity, but I believe that A. Scott Berg’s biography does paint a picture of a quite simple man who was not as his daughter wrote above—”a hater.” He like so many did “hate” war and its effects on humanity—Gaza comes to mind today; and like so many he only saw afterwards how there are conditions “worse than war” that only war can stop.

I agree with Reverend S. Parkes who wrote in 1928: “Any war is moral that redeems us from a state of things worse than war itself. I am willing for any war to be waged if you can show me that it is saving us from conditions worse than a state of war.”

I agree with Reverend S. Parkes who wrote in 1928: “Any war is moral that redeems us from a state of things worse than war itself. I am willing for any war to be waged if you can show me that it is saving us from conditions worse than a state of war.”

- Understanding the Man—Charles Lindbergh and His Family Life

Charles Lindbergh was known for his lists, the things he had to get done. These lists seemed to have been outwardly focused to benefit others: aviation, culture, and society. They were not self-serving lists, but they did affect his sense of priorities. Recently a country-western singer passed away: Toby Keith. One of my favorite songs that helped me in my life was his song, “My List.” Reading this book, I often wondered if Charles Lindbergh had heard this song in his day—and paid attention to its overall message—he might have dealt with his successes and failures better.

|

Reading this biography, it seems that the chorus for the song might have given him and his wife a better life: “Under an old brass paperweight is my list of things to do today. … I cross them off as I get them done but there’s still more, I haven’t got to yet …” such as:

Go for a walk, say a little prayer

Take a deep breath of mountain air Put on my glove and play some catch It’s time that I make time for that Wade the shore and cast a line Look up an old lost friend of mine Sit on the porch and give my girl a kiss Start living, that’s the next thing on my list. |

Father kissing daughter

|

Over and over again the diaries of Charles and Anne Lindbergh reveal the truth in the chorus above. Time alone—isolated from the societies of hero worship that pursued them, they came closer together, reunited, and reaffirmed their love. It was just with the tremendous pressure that mankind’s idolatry put on the two of them and their family that they needed even more time to take deeper breaths, to say more prayers, to play a lot of catch, and to give each other a kiss.

This Pulitzer Prize winning biography is the life story of Charles Lindbergh but, even more than that, it is an examination of the troubles that result from unrestrained “hero worship.” The resulting dilemmas and complications of such idolization are not just confined to a society’s icon. As seen in this highly, diary-documented, memoir, the problems penetrate the lives of the idolized individual’s surrounding family and friends, and bubble up to a froth to permeate and sicken society as well.

As quoted in the book, Charles Lindbergh could have never anticipated the “unforeseen opportunities, responsibilities, and problems” of his successful crossing of the Atlantic in The Spirit of the St. Louis. This book does a wonderful job documenting the opportunities and responsibilities, but what A. Scott Berg does best is a superlative job exploring and making the reader understand the problems of hero worship which seem deeply rooted in our human nature! The book left me asking this question: “Can we accept flaws in our heroes and heroines—all of whom, because they are only human, will always be less than perfect?

Human beings are complicated and their motivations—which are critical in understanding an individual’s actions—is one of our most hidden traits. Why? This is a question which is asked repetitively by many two year olds who are simply told “Because!” They can become adults who want to simplify and summarize a human being’s life and times down to a short witticism of praise or a condemning platitude of misconduct—hearsays. Scott Berg used a phrase in this book: “Yesterday’s hearsay has become today’s history.” This expression encapsulates much of what I have found as I continue my research of the actions and the motivations of the men and women of prominence who have lead America in many of its professions in the early to mid-twentieth century.

After reading this book—and so many like it, I would comment: “Our history today is tainted with too much hearsay generated by those who repeat shallow, unresearched, misconceptions as truth.” As individuals, we seem afraid to display our ignorance and simply comment, “I know nothing of him or her, but would appreciate your thoughts on the individual along with your logical explanation why you think these things, and—by the way, the material upon which you base your opinions.”

This Pulitzer Prize winning biography is the life story of Charles Lindbergh but, even more than that, it is an examination of the troubles that result from unrestrained “hero worship.” The resulting dilemmas and complications of such idolization are not just confined to a society’s icon. As seen in this highly, diary-documented, memoir, the problems penetrate the lives of the idolized individual’s surrounding family and friends, and bubble up to a froth to permeate and sicken society as well.

As quoted in the book, Charles Lindbergh could have never anticipated the “unforeseen opportunities, responsibilities, and problems” of his successful crossing of the Atlantic in The Spirit of the St. Louis. This book does a wonderful job documenting the opportunities and responsibilities, but what A. Scott Berg does best is a superlative job exploring and making the reader understand the problems of hero worship which seem deeply rooted in our human nature! The book left me asking this question: “Can we accept flaws in our heroes and heroines—all of whom, because they are only human, will always be less than perfect?

Human beings are complicated and their motivations—which are critical in understanding an individual’s actions—is one of our most hidden traits. Why? This is a question which is asked repetitively by many two year olds who are simply told “Because!” They can become adults who want to simplify and summarize a human being’s life and times down to a short witticism of praise or a condemning platitude of misconduct—hearsays. Scott Berg used a phrase in this book: “Yesterday’s hearsay has become today’s history.” This expression encapsulates much of what I have found as I continue my research of the actions and the motivations of the men and women of prominence who have lead America in many of its professions in the early to mid-twentieth century.

After reading this book—and so many like it, I would comment: “Our history today is tainted with too much hearsay generated by those who repeat shallow, unresearched, misconceptions as truth.” As individuals, we seem afraid to display our ignorance and simply comment, “I know nothing of him or her, but would appreciate your thoughts on the individual along with your logical explanation why you think these things, and—by the way, the material upon which you base your opinions.”

The biggest compliment I could pay this book is that when I state my opinion of who Charles Lindbergh was and what he did or did not accomplish in his life, I will state that my opinions are based on what I believe to be one of the most balanced, authentic, and dignified studies that a biographer has accomplish on any man. All of us, who are all flawed to some degree, needs an understanding of an individual’s motivations, their drives and their beliefs—even those which we might find worthy of admiration or deserving of disapproval. We should learn from another’s accomplishments and mistakes.

When we write our opinions, Mr. Berg offers some insights into these writings by quoting W. H. Auden, “Everything one writes goes out helpless into the world to be turned to evil as well as good … every work of art is powerless against misuse.” Even this book review may be used by those who have hidden agendas and biases—as every work is powerless against misuse, especially if we fail to meet each other on our unique and varying platforms of understanding. At least in democracies, we can meet as peers to discuss our views. May we both be open to higher levels of understanding gained through access to historical knowledge.

Scott Berg accomplished this for me in this work of his about Charles Lindbergh.

I understand the man better … both his strengths and his failings.

Learn from another’s mistakes, eh?

Cheers,

- Peter E.

When we write our opinions, Mr. Berg offers some insights into these writings by quoting W. H. Auden, “Everything one writes goes out helpless into the world to be turned to evil as well as good … every work of art is powerless against misuse.” Even this book review may be used by those who have hidden agendas and biases—as every work is powerless against misuse, especially if we fail to meet each other on our unique and varying platforms of understanding. At least in democracies, we can meet as peers to discuss our views. May we both be open to higher levels of understanding gained through access to historical knowledge.

Scott Berg accomplished this for me in this work of his about Charles Lindbergh.

I understand the man better … both his strengths and his failings.

Learn from another’s mistakes, eh?

Cheers,

- Peter E.