Evaluating Bernard M. Baruch's Comments on Judge Gary

|

Bernard M. Baruch wrote in his opening Preface of My Own Story:

I have always felt a man’s memoirs should be published while he is still alive so that those who might object to what is written would be able to confront the writer with their views. This is admirable, but Mr. Baruch died in 1965 at the age of 94 years of age, and he published his two books only a few years before his death: 1957 and 1960. By the time he wrote these books, most of the individuals he writes about were dead. So, few would have been able to “confront” the author.

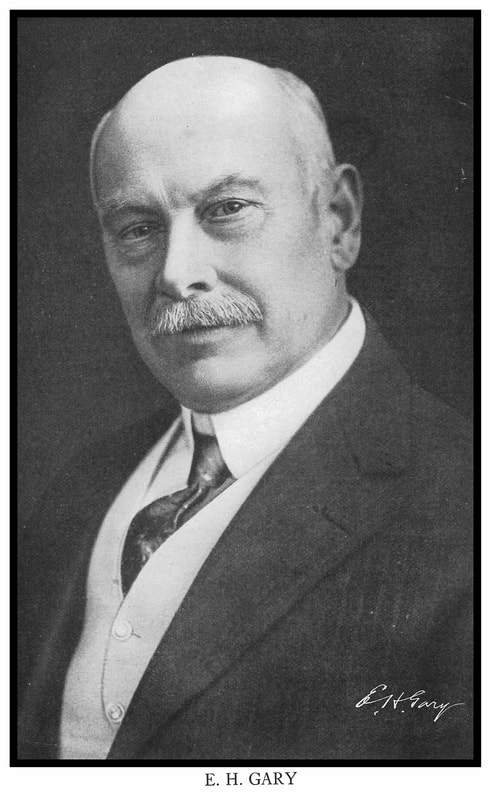

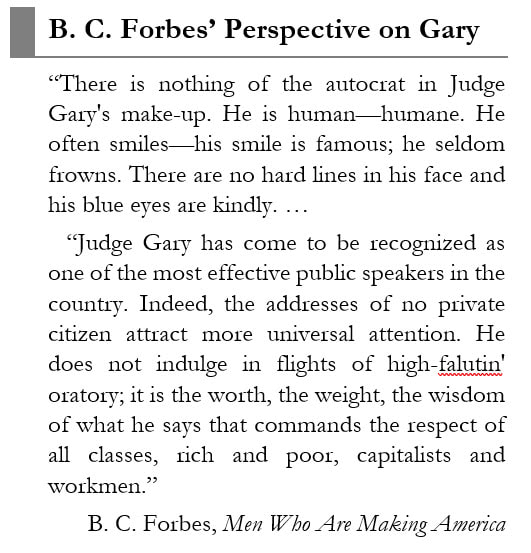

Confront is also a rather strong word. I believe that at least one of the individuals would have liked to have submitted his two cents—a different perspective. This approach would have been in the character of Judge Elbert H. Gary, Chief Executive Officer of the United States Steel Corporation: he appears to have been a non-confrontational and rather soft spoken individual, given to allowing men time to digest their thoughts. Mr. Baruch might have considered following the statement above with this paragraph: |

Many have gone before me. Their memoirs, biographies and autobiographies have put forth their stories, and history is the story of many individuals’ interactions. Where there is some overlap, such as in my dealings with Judge Elbert H. Gary, I have tried to address the stories in his biography as best I can, and put forth to the public not only what I observed—both supportive or contradictory—within the context of what was written before me. Most of those I write about in these memoirs are not alive. They cannot confront this writer, so, I will attempt to add context around what others have written.

Of course, it is obvious that in a room full of individuals with difficult topics to discuss there will always be many viewpoints. Mine should be considered just one more perspective—in most cases it is possibly the last words of one who attended these events.

May historians dig deeper and in the future bring more enlightenment.

In this respect, though, he fails the readers of his autobiographies, and he fails to provide what could have been a more complete, updated and thorough understanding of the history of Corporate America. This article is to highlight one such failure with one man for which there is much more substantial and, at times, contradictory evidence. Mr. Baruch seems to have failed in his evaluation of Judge Elbert H. Gary.

Given that the two sources of events sited in this article were written in 1925 and 1939, The Life of Elbert H. Gary: The Story of Steel and All in the Day’s Work, respectively, Mr. Baruch had plenty of information and time to digest these facts and add his perspective.

He failed, though, to elaborate, and instead, he seemed to let generalizations rule.

Given that the two sources of events sited in this article were written in 1925 and 1939, The Life of Elbert H. Gary: The Story of Steel and All in the Day’s Work, respectively, Mr. Baruch had plenty of information and time to digest these facts and add his perspective.

He failed, though, to elaborate, and instead, he seemed to let generalizations rule.

Bernard Baruch’s Two Interactions with Judge Elbert H. Gary

|

Mr. Baruch through his two books offers some views of Judge Elbert H. Gary. In My Own Story his first not-so-delicate brush stroke describes his perception of Judge Gary:

In Gary, Morgan surely found a personage as different from Schwab or Gates as day is from night. And as different from Morgan, too, for that matter. If Elbert Gary ever had any fun in his life, I don't know how he did it. The description making Gary as different from Schwab “as day is from night” was not meant in a complimentary sense. Of course, this was a personal insight, but it seems to flow over into his overall analysis and perceptions of Judge Gary in The Public Years.

|

His perception surfaces during some especially tough negotiations over price controls at the start of World War I. The best way to describe the interaction was that Baruch saw the negotiations between government and industry as black and white, while Gary was trying to find a middle ground between the government and his entire industry which had obligations to all its stakeholders as well as society—for him, solutions were found in many negotiated shades of gray after long discussions which were followed by time to think.

Bernard M. Baruch’s perspective:

The need to control steel prices became urgent. The first step came in the summer of 1917 when, as Chairman of the Raw Materials Committee, I went to Judge Elbert H. Gary, the redoubtable head of the United States Steel Corporation, to ask him to cut the price of ship plates ordered by the Navy and Shipping Board. … Four-and-one-quarter cents was the price Gary had asked for the ship plates.

I knew it to be far too high. …

He then goes on to elaborate how he went about finding a price that would have worked for U.S. Steel Corporation, which was one of the largest, integrated steel producers in the world, but also a price which would have meant that the smaller vendors—who still had 60% of the steel business—produce at a loss and be unable to pay wages or build new facilities the government needed to meet urgent wartime production schedules.

He summarized a complex situation and a tense meeting with this generalization:

He summarized a complex situation and a tense meeting with this generalization:

"Ford, Gary, and Dodge typified the problem which WIB [War Industries Board] faced in educating American businessmen to the new facts of life. They had not made the transition in their thinking from Main Street to Washington, and their values were still the values of the marketplace. |

He also added this as a comment leaving a tone of suspicion around the steel industry in general and Judge Gary in particular:

"The steel industry accepted these new prices in good faith, and they remained almost unchanged till the end of the war. It has been estimated that this regulation of steel prices saved the government more than a billion dollars. The steel industry also did a superb job of production; but there is no question that profits, especially of the great integrated companies, were still excessive [emphasis added]."

|

No facts were presented for the last statement emphasized by this author above. Mr. Baruch expects his reader to accept this statement as fact without supporting evidence. This author questioned Mr. Baruch's "no question that profits ... were still excessive."

Baruch’s perspective seems completely out of character with the man described by Ida M. Tarbell in two of her books: The Life of Elbert H. Gary: The Story of Steel published in 1925 and her autobiography, All in the Day’s Work: An Autobiography, published in 1939. Of the two individuals, Miss Tarbell’s account of Judge Gary, during this same time period—even some of the same early meetings—she supports with direct information and quotes from other leaders of other commissions, committees and government agencies—of which there were many. |

Read a Review of Ida Tarbell's "The Life of Elbert H. Gary."

|

Evidently, they had formed a much different opinion of Judge Elbert H. Gary from Bernard M. Baruch, and Miss Tarbell did due diligence including this information in her works.

Additional Insights into the Character and Efforts of Judge Elbert H. Gary

Ida Tarbell writes that upon working through a complicated matter with the Navy Department [mentioned above by Mr. Baruch], the Secretary of the Navy Daniels spoke “warmly of the help he received from the Corporation, saying that in early negotiations Judge Gary “showed the patience of a statesman who understood that you must give time to allow the mental column to close up.”

R. S. Brookings, Chairman of the Price-Fixing Committee, who worked constantly with Gary wrote:

R. S. Brookings, Chairman of the Price-Fixing Committee, who worked constantly with Gary wrote:

As Chairman of the Price Fixing Committee it was my privilege to be very closely associated during the war with Judge Gary, who was spokesman for the entire steel industry. As steel was the keystone of our war needs and maximum production at a fair price was no easy problem, I have only the greatest admiration for the fairness and skill with which Judge Gary met the views of the Government and at the same time, reconciled and satisfied the great variety of interests which he represented [emphasis added].

Mr. Replogle, cited in Mr. Baruch’s information above said at a gather of the steel committees:

In the early stages of the game, when we were in great distress for some material for General Pershing, we came to Judge Gary [Chief Executive Officer of U.S. Steel Corporation] and Mr. Farrell [President of U. S. Steel Corporation]; and despite the fact that they were loaded up, they turned in—they had taken seventy per cent of all the Government orders placed at that time, which was far in excess of their capacity, and yet they absolutely took that [work] without question and gave General Pershing the material when and as he needed it.

Miss Tarbell even goes so far as to document the earnings of the U.S. Steel Corporation showing the impact of the government’s wartime policy on prices. It is hard to say that the steel company was profiteering as gross earnings went up by 56% but the bottom line, net income after taxes went down by 16%. The corporation was not only contributing its production to the government for the war effort but, through taxation, was a major contributor to this mighty struggle between nations, their military and their economies.

This was during a time when great funds were being expended to build new facilities to support the war effort as discussed in the following abbreviated story.

This was during a time when great funds were being expended to build new facilities to support the war effort as discussed in the following abbreviated story.

Extraordinary tasks were put upon the Corporation—tasks in which they had had no experience—which demanded huge sums of money and which would be dropped at the end of the war, such as building ships [emphasis added].

They were asked in the summer of 1917 to assist in meeting what was realized as one of the most formidable weaknesses of the [war] situation. ‘‘We did not wish to go into the business of building ships,” Judge Gary told his stockholders at their next meeting. “It was entirely out of our line; but we were approached by Government representatives to see if we could assist in building ships at a time when they were so much needed. And after making a careful study of the situation we decided we could build them at least as cheaply as anyone else, and at least as rapidly as anyone else, that we could get into the business as soon as anyone else, and that we could build a style and character of ship that would be practical, efficient and satisfactory to the Government.”

Two plants were started, one on the Hackensack River, the other at Mobile, Alabama. When Judge Gary talked to his stockholders [later] he told them, “amid applause” [from shareholders], that the first ship was to be launched in May—nine months after they broke ground—and that, beginning in July, the Corporation’s two plants would furnish a complete ship every ten days.

This was followed with details in Miss Tarbell’s book about building a munitions facility to produce “Twelve 14-inch 50-caliber guns—or equivalent—and of 40,000 shells per month.” Judge Gary sent the contract to the federal government as follows:

The contract provided that the Corporation should take entire charge of the design, construction, and operation of the plant, subject to approval of general plans by the Secretary of War, and that it should be reimbursed for only the exact cost of outlays made directly for the work which, in accordance with the offer of the Corporation, included no compensation for the service of its officials, experts, or its general organization in supervising the work; nor for the interest upon considerable sums advanced for the payment of labor, material, and other construction expenditures [emphasis added].

Some final facts seem to highlight Mr. Baruch’s failure to fully comprehend the hesitancy Judge Gary showed in making concessions to the government on requested pricing actions. Price concessions that U. S. Steel Corporation could have easily made, would have put others out of business. Those other firms within his industry—which he represented in meetings with the government—which were smaller and less integrated, could not afford such low prices or else they would have missed payroll or been unable to expand facilities as needed by the government.

Judge Gary even went so far as to help his “competitors” and utilized good business judgement to compensate for bad government decisions, or decisions by individuals who lacked industry-specific knowledge.

Miss Tarbell documented:

Judge Gary even went so far as to help his “competitors” and utilized good business judgement to compensate for bad government decisions, or decisions by individuals who lacked industry-specific knowledge.

Miss Tarbell documented:

He [Judge Gary] never failed to help a competitor. Frequently a concern found itself short of materials required for an order allotted and to be delivered by a certain date. Mr. Farrell, under Judge Gary's instructions, supplied them, whether it was billets or nuts, and at a price below his own cost if the other concern stood to lose on the contract, as was sometimes the case. They must be allowed to make a little money if they were to carry on [emphasis added].

Such transactions were frequent throughout the war.

There were voluntary acts of foresight which prevented disasters. For example, the Washington purchasing bureau refused to provide extra supplies of manganese. It [the government believed] would not be needed. Judge Gary and Mr. Farrell knew better, and the Corporation laid in 600,000 tons. When the shortage came, they sold to their competitors at the price they had paid. The close of the war found them with 200,000 tons on hand.

This author in thinking over this last set of situations and appropriate and ofttimes benevolent actions by Judge Gary and his associates believes that if the U.S. Steel Corporation had a “predatory intent” it could have easily used the war situation to consolidate its power over the industry. It could have forced its smaller competitors out of business with its industry foresight and pricing actions agreed to by the government.

Judge Gary seemed to have the first, best interest of his nation and his industry at heart, not his corporation and certainly not any “unenlightened, personal self-interest.”

Judge Gary seemed to have the first, best interest of his nation and his industry at heart, not his corporation and certainly not any “unenlightened, personal self-interest.”

The Author’s Evolving Thoughts on Bernard M. Baruch and His Autobiographies

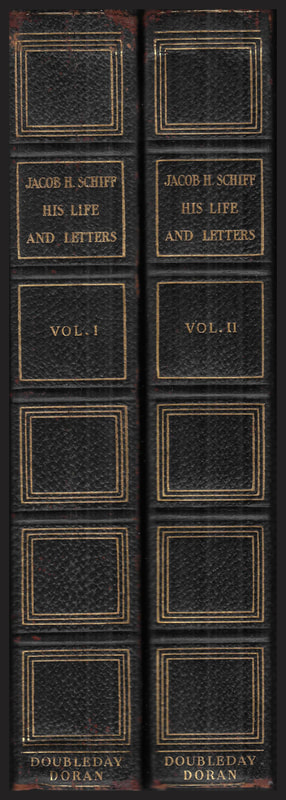

After reading Bernard M. Baruch’s works, I then read the life of Jacob H. Schiff. This is a two volume set entitled: Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters. Both men were “capitalists.” There was a very real difference, though, between the two men. They were on different ends of the capitalist spectrum.

|

Schiff “built things” with his capital and the capital of his investors, probably what most industrialists would have called a good capitalist. This comes across very strongly in Schiff’s biographical work. Baruch comes across in his autobiography as more on the speculative side of capitalism—closer to a Wall Street player. Henry Ford not the most gentile in this area probably captured the extremes of these two players in this quote of his about “shareholders.”

He wrote: Stockholders … ought to be only those who are active in the business and who will regard the company as an instrument of service rather than as a machine for making money. Henry Ford, My Life and Work

|

Read Review

|

Jacob H. Schiff saw his part in society as an instrument of service. Although service was at the heart of Bernard M. Baruch also, his story in My Own Story, places him firmly in the area of speculator in capitalism—a machine for making money, not a builder of capitalism—one who is active in the business and considers a business as an instrument of service.

Is there something wrong with speculation? I think on that question, many good men will differ. Even Baruch himself knew that speculation could go too far. He called it gambling. How many arguments start over—or how many reasonable men dodge their responsibilities with—semantics?

It would have been interesting to have compared the perspective of Schiff and Baruch on Judge Gary, but there is no mention of Gary in Jacob Schiff’s two-volume biography, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters.

I learned from this experience to be careful referencing “authoritative sources.” I believe that all men are human, and that Baruch either never read, failed to read, or for some other (so far) undiscovered reason failed to consider the additional published works that discussed Judge Gary.

But isn’t this human? Yes, but disappointingly so for Bernard Baruch, a man who was obviously so well spoken and so highly perceived by the public and by many of his peers. I expected more and … I need to be more careful in my own writings.

This is my lesson learned concerning this second thoughts on a first review: humility.

Cheers,

- Pete

Is there something wrong with speculation? I think on that question, many good men will differ. Even Baruch himself knew that speculation could go too far. He called it gambling. How many arguments start over—or how many reasonable men dodge their responsibilities with—semantics?

It would have been interesting to have compared the perspective of Schiff and Baruch on Judge Gary, but there is no mention of Gary in Jacob Schiff’s two-volume biography, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters.

I learned from this experience to be careful referencing “authoritative sources.” I believe that all men are human, and that Baruch either never read, failed to read, or for some other (so far) undiscovered reason failed to consider the additional published works that discussed Judge Gary.

But isn’t this human? Yes, but disappointingly so for Bernard Baruch, a man who was obviously so well spoken and so highly perceived by the public and by many of his peers. I expected more and … I need to be more careful in my own writings.

This is my lesson learned concerning this second thoughts on a first review: humility.

Cheers,

- Pete

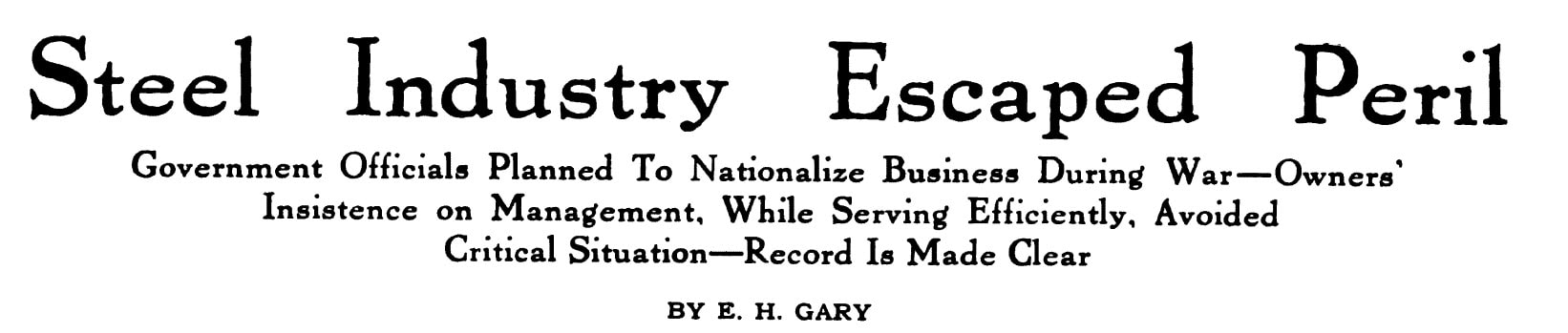

Postscript: There was a conflict in the press between Bernard M. Baruch and Elbert H. Gary. Mr. Baruch took exception to an accounting by Judge Gary at a steel conference that the government at one time during World War I intended to nationalize the steel industry. This was actually supported by what Baruch wrote later in his memoir, The Public Years.

The speech by Judge Gary that Mr. Baruch took exception to seems quite balanced in its nature while still expressing the viewpoint of a whole industry of owners toward the proposition: they fought it.

But as Gary stated:

The speech by Judge Gary that Mr. Baruch took exception to seems quite balanced in its nature while still expressing the viewpoint of a whole industry of owners toward the proposition: they fought it.

But as Gary stated:

It is only fair to say that, after a long experience with the war industries board, all in all the steel committee could not, nor had any inclination to, challenge the wisdom, fairness and inclinations of this board, from Mr. Baruch down. We did not always agree with them. Quite the contrary. Some of us thought at the time some decisions were wrong and unjust, but considering everything, we now believe they were justified in their conclusions.

Select the image to download Judge Gary's speech. It is hard to see why Mr. Baruch took exception to it. Let me know if, after reading it, you perceive it otherwise!