Review of Armour's "The Packers, Private Car Lines and People"

|

|

Date Published: December 20, 2020

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

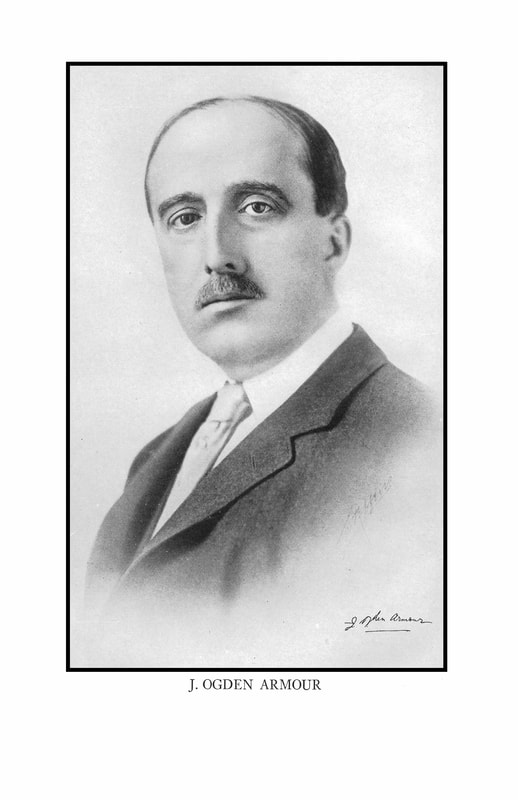

B. C. Forbes initiated this journey of mine with his analysis of Mr. J. Ogden Armour in his 1917 work, Men Who Are Making America—written a decade after this flurry of flaming media articles and political rhetoric. When I started this short project, all I knew was what I memorized for a multiple choice test in grade school: The Jungle was the force behind the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

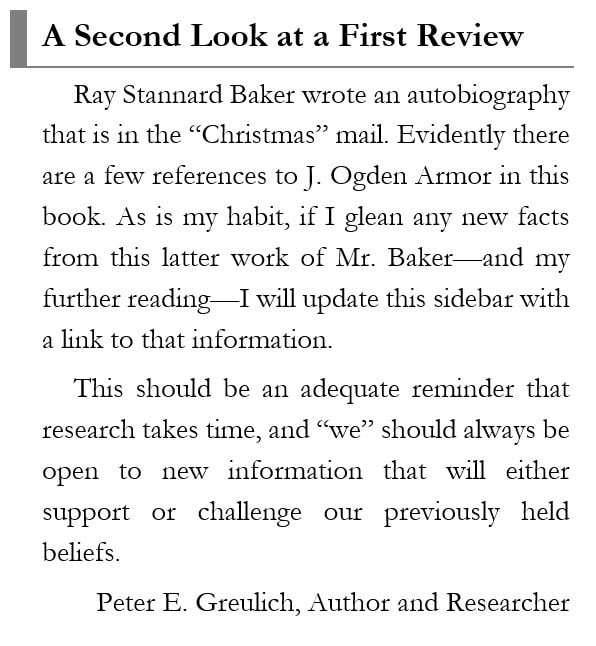

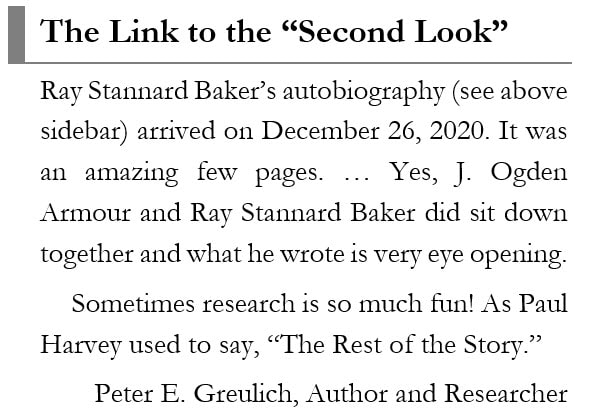

In 1906, J. Ogden Armour responded to multiple attacks on his industry and his company with the book, The Packers, the Private Car Lines and the People. Upton Sinclair’s fictional—supposedly based on fact—novel, The Jungle, provided the impetus, and a McClure’s Magazine journalist—whose talent I greatly respect—joined in the fray [In fact, his perspective started my practice of sometimes providing "A Second Look at a First Review."] So, my interest was piqued.

The Packers is a smartly written, factually-driven book. For his stand, Mr. Armour received the 20th Century equivalent of what we see all too often today on social media: character assassination, political and ministerial condemnation from their respective pulpits, the media piling on, and even death threats. To all of this he responded with a level, but strong and determined tone.

Let’s follow the latest book review format: (1) reviews of the day, (2) quotes from the book, and then (3) this author’s thoughts on this work of J. Ogden Armour.

In 1906, J. Ogden Armour responded to multiple attacks on his industry and his company with the book, The Packers, the Private Car Lines and the People. Upton Sinclair’s fictional—supposedly based on fact—novel, The Jungle, provided the impetus, and a McClure’s Magazine journalist—whose talent I greatly respect—joined in the fray [In fact, his perspective started my practice of sometimes providing "A Second Look at a First Review."] So, my interest was piqued.

The Packers is a smartly written, factually-driven book. For his stand, Mr. Armour received the 20th Century equivalent of what we see all too often today on social media: character assassination, political and ministerial condemnation from their respective pulpits, the media piling on, and even death threats. To all of this he responded with a level, but strong and determined tone.

Let’s follow the latest book review format: (1) reviews of the day, (2) quotes from the book, and then (3) this author’s thoughts on this work of J. Ogden Armour.

A Review of "The Packers, the Private Car Lines, and the People" by J. Ogden Armour

- Reviews of the Day: 1906–07

- Selected Quotes from The Packers

- This Author’s Thoughts on J. Ogden Armour and His Book

[Disclaimer: After completing my service with the U. S. Army in Germany, I worked at Iowa Beef “Packers” in Amarillo, Texas and Emporia, Kansas for a subcontractor named Packers Sanitation Services Inc. I was grateful that they hired veterans, grateful for the paycheck, and grateful for the life experience of working within the packing industry. It was tough washing blood and guts off walls and machinery, but it was a tremendous learning experience for a youth in his twenties. It did convince me to take advantage of my G. I. Bill and go back to school. I believe this experience flavors this article only slightly, but the reader should be aware.]

Reviews of the Day: 1906–07 (published in June 1906 by the Henry Altemus Company)

|

“Frankly admitting that he is writing in self-defense, Mr. J. Ogden Armour in ‘The Packers’ … has the advantage over hysterical alarmists of knowing what he is talking about. The details of the great business he treats of, the workings, the difficulties, the complications and the methods are all described. There may be difference of opinion as to the author’s view of matters, but his presentation of facts is clear.”

The New York Sun, June 16, 1906

“[In The Packers] Mr. Armour did not overestimate the value of inspection to the packing house interests. … One would think that from selfish reasons they would be concerning themselves with the need of immediate legislation. … So far as the cost of inspection is concerned, they are probably losing enough business every week to pay the inspectors for a year."

The Vicksburg Herald, June 19, 1906

|

“Those who are interested in getting at the packers’ side of the agitation over the so called beef trust and its methods will find this a valuable book. It should also be of interest to the general reader, in as much as its subject is one of the largest of our national industries.”

The Chicago Inter Ocean, June 23, 1906

“The most interesting chapter in the book is the fifteenth and last, because it deals by anticipation with the charges that have since the serial publication of the previous essays found their most relentless advocate in Mr. Upton Sinclair.”

The Nashville Tennessean, June 24, 1906

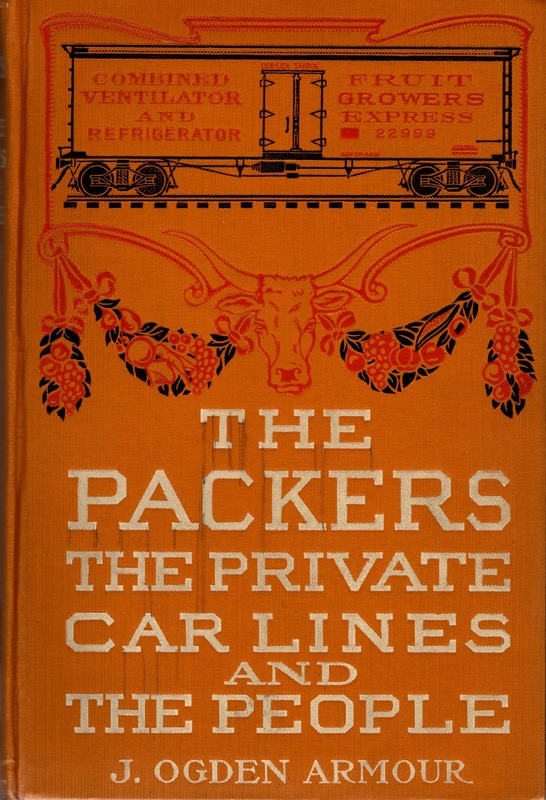

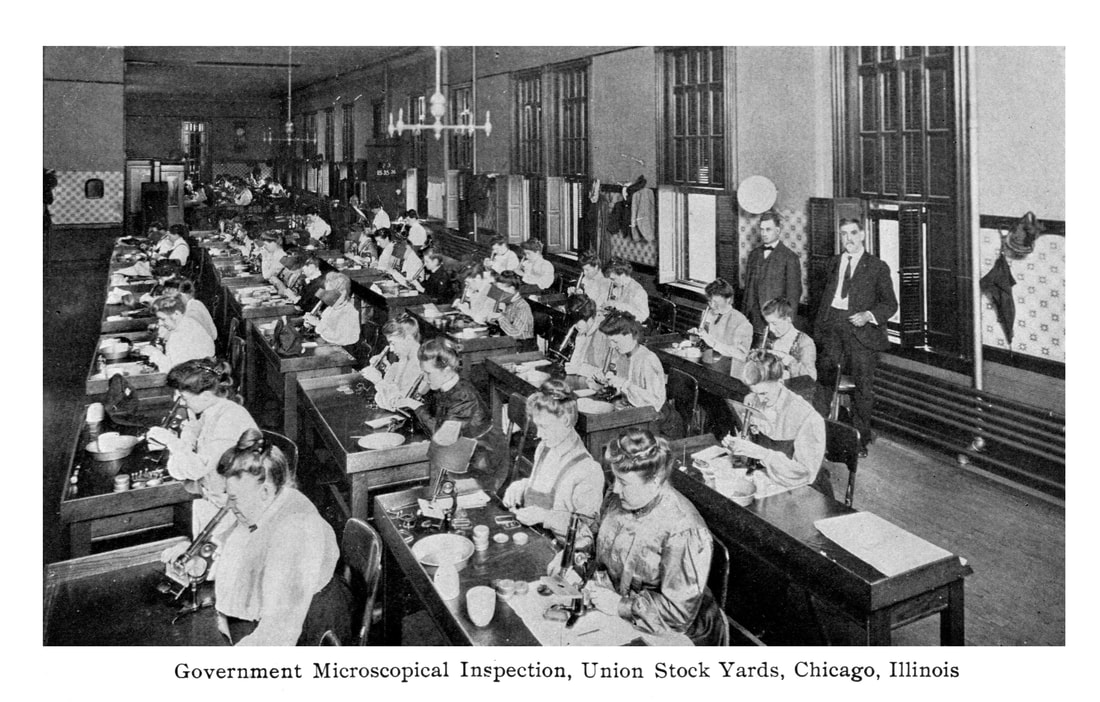

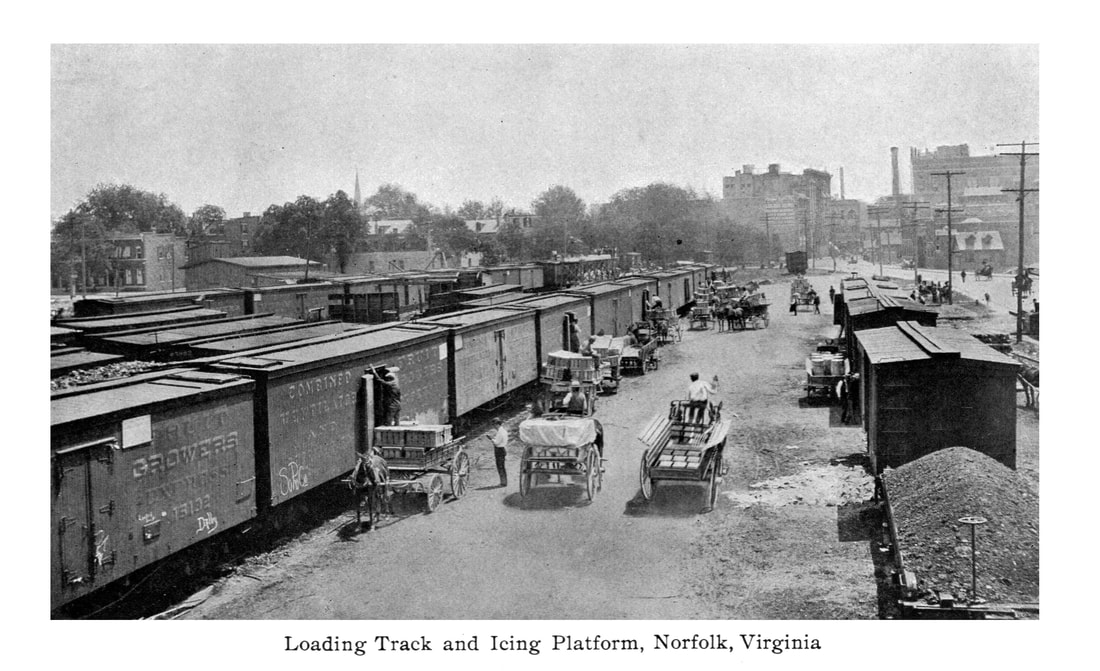

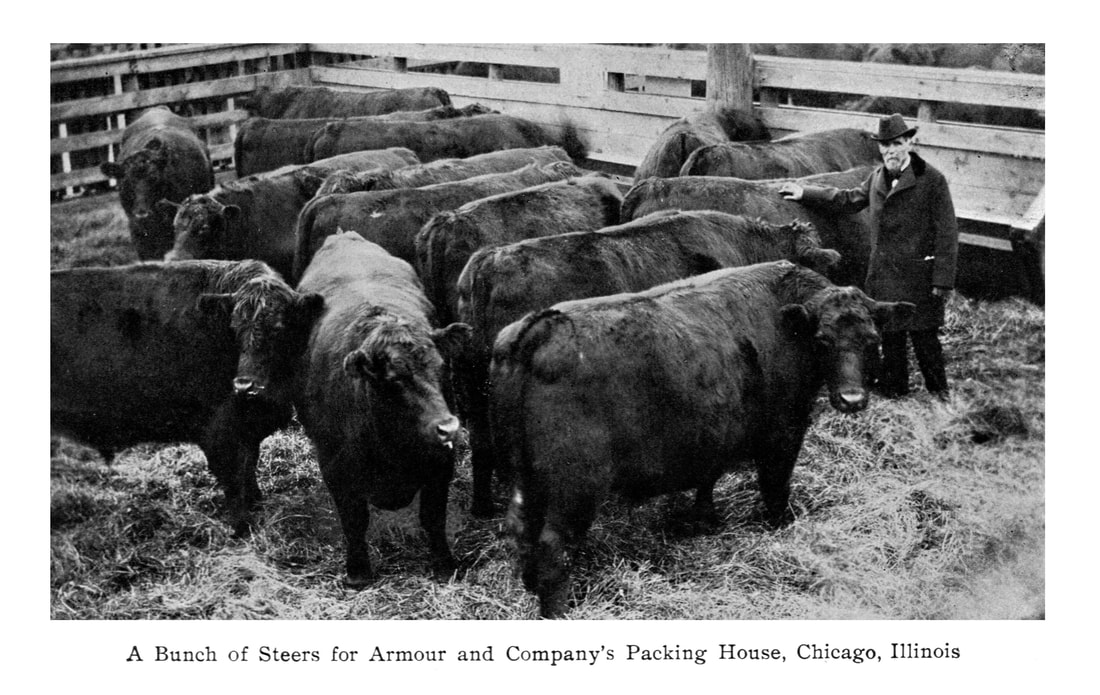

As usual in my reviews, I like to point out chapters that I think are outstanding or of the most significance, and I agree that the “fifteenth and last” chapter is the most interesting. The following picture is from that chapter.

Now, let’s look at some quotes extracted from the book.

Selected Quotes from The Packers

- This is one of my favorite passages from the book comparing the pioneers in the packing industry to that of an artist. From the 21st Century entrepreneurs I have had the pleasure of meeting, it describes them quite succinctly.

“The original packers were born into a commercial age. They were filled with the spirit of the times. They saw opportunities lying at their feet—opportunities to widen their own commercial field and that of all around them—opportunities to create new enterprises—opportunities, if you please, to make two blades of grass grow where but one grew before. Made as they were, they could no more smother their energies than the born artist can keep his fingers out of the paint box.

“They jumped in, and the pioneering, the creating, and the organizing achieved by them and men of their stamp, has played a large part in making this country the marvel of history in rapid development and commercial expansion [emphasis added].”

- And another wonderful quote on the purpose of “self-interest” in these driven pioneers—again applicable to today’s entrepreneurs.

“The business genius and commercial pioneering, the enterprising, organizing and executive abilities of the original packers have been among the most potent influences in building up the country. Why shouldn’t they be entitled to some credit for it?

“They were looking out for themselves when they were building those businesses. Of course they were. But that is no answer. If we examine the intimate personal annals of the heroes of history, we shall find but few who started upon their respective roads lighted only by the pure white flame of holy resolve to uplift humanity. "

“Blink at it as we may, there is a touch of self-interest in the best of men.” - Yet, he also understands the public’s concern with the possibility of being overcharged for what was quickly becoming in 1906 a staple, a necessity, on their tables—that which only a few years before was unavailable: fresh meats, fruits and vegetables.

“Those purchases which give pleasure are not the basic necessities of life; they are the luxuries, or at least the finer comforts. And it is human nature to think how many of these coveted things could be bought with the money which must be paid out for meat and the other articles of food. Thus the daily meat bill seems to stand constantly between the consumer and some coveted comfort, some article of beauty, some greatly desired luxury or pleasure.

“And because it does so stand—so far as the feelings of the purchaser are concerned—it provokes an unreasoning resentment of which the packer is invariably the convenient target.”

- He takes the position that much of the anger directed at the packers is the work of the “commission men” or “middlemen” who are being removed from the revenue picture to the benefit of the ranchers, farmers and packers.

“For assistance in this they [these commissioned middlemen] rely much upon that trait in human nature which always enables a falsehood to travel faster than the truth, and they have chosen an apt time for such a campaign—a time when the public mind has been poisoned by ‘yellow’ agitation against everything bearing the name of corporation, and by demagogic appeal for political effect.” - J. Ogden Armour spends significant time educating his reader on the differences between his industry and others. He summarizes the difference between transferring raw materials (such as oil, steel and coal) and “perishable” raw materials (like meats and fruits), J. Ogden Armour writes:

“The general run of manufacturers of any considerable size handle raw materials which are not perishable in the usual sense of the term. Even when their raw materials are perishable they become less so, if not practically imperishable, as soon as passed through the manufacturing process.

“The packer uses a material that is quite perishable, and a large part of his finished product—fresh meats—is highly perishable; so he is taking risk at both ends of his business.” - He also suggests that profit margins are more in alignment with the grocery store industry than the oil or steel industries. Grocers make their money by moving large volumes of goods at small profit margins.

“The industry exemplifies the ideal business theory of “quick returns and small profit.” It gathers the product of the millions of small producers throughout the Western Empire stretching from the Alleghenies to the Rocky Mountains, converts their product into merchantable commodities, and distributes them to the consumers of the whole round world.

“For the service it performs, it is none too well paid in the profit it makes—an average of less than two percent on the volume of business handled.”

With this final statement let’s start the review.

This Author’s Thoughts on J. Ogden Armour and His Book

|

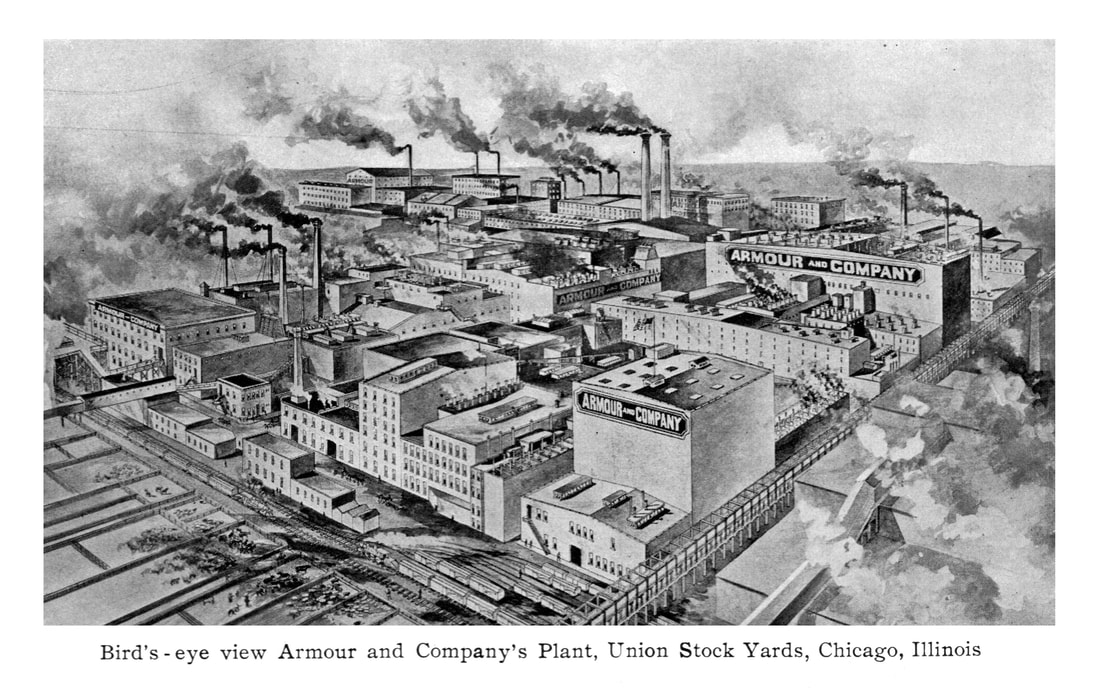

Personally, I was unaware of the immensity of the packer business. At the time of the writing of the book Mr. Armour quotes that his industry sold abroad $233,000,000 worth of meat animals (cattle, hog and sheep), meats (processed) and meat products. In comparison breadstuffs (wheat products) were only $154,000,000, iron and steel exports were only $90,000,000, and copper products only $85,000,000.

In many ways, reading the history behind this “Beef Trust” episode was the observation of the struggle between two individuals of unusual reasonableness [J. Ogden Armour and Ray Stannard Baker] and a public held spellbound by the work of a propagandist [Upton Sinclair]. Armour and Baker brought forth opposing cases of great fact and information, and one wonders if the two, if they could have gotten in a room together, might have sorted through their divergent observations. What does come across is that both cared about the industry and the American people. It is easy to believe that both would be amazed at the American and worldwide food distribution network which resulted from this period of American history. |

Mr. Ogden at several points in the book eloquently verbalizes what I constantly remind my readers, “Business environments can change overnight. Businesses must be prepared for such changes. Businesses could change almost as quickly, but human beings evolve over eons—such that writing about a “century of human evolution” seems like an oxymoron. This can delay change even at its very best, for extended periods of time. We still get into conflicts: we fight; we get angry; we state our facts with all the conviction possible; and yet, we still won’t sit together around a table and just talk to resolve our differences and find solutions.

|

Ray Stannard Baker paints a credible picture of misconduct on the part of Armour & Company. Although the titles of his articles were directed at the railroads—The Railroad Rate and The Railroads on Trial—Armour & Company and the packing industry were complicit in the controversy.

Some of Mr. Baker’s points would not be considered a problem today, such as filling the railroad cars with freight at below-cost rates rather than sending the cars back empty on the return leg of a round trip journey. This is common sense. The balance in his articles do capture the evolving picture of capitalism in the United States—the difference between the business environments of a father and his son: |

|

"[Philip D.] Armour, the father, lived in halcyon time when rights were chiefly emphasized, and force was more highly prized than justice. [J. Ogden] Armour, the son, has reached the day when the people are demanding what service rich men have done the people in return for their privileges and immunities.

For it is not only that Armour’s methods have grown more exacting, but that the people’s ideals of social responsibility have risen to a higher plane." |

Progressing as a society to a higher, socially responsible plane is of the greatest importance, but I also understand that was a gradual process with times of backsliding and frustrating compromises. Men and women must meet on the battleground of ideas and ideals. To me, this was a battleground well deserving of government intervention. This is one reason I read these older works. The struggles of yesteryear are still today’s struggles because human nature seems immutable within a century’s time and the media still taps humanity’s emotions—only now it is for “clicks,” not “subscriptions.”

As a referee between the perspectives of Upton Sinclair, Ray Stannard Baker and J. Ogden Armour I referred to what I consider one of the greatest single works of American History: Mark Sullivan’s Our Times. His section on “The Crusade for Pure Food” is an amazing read that cuts across all of this information and provides a cohesive believable historical timeline [too much to be presented here]. In a footnote, he positions the works of Upton Sinclair and Ray Stannard Baker of McClure’s Magazine.

The following footnote to history is a long read but well worth the insight for those who, like me, just remember The Jungle’s significance from a multiple-choice test with no context that was either never taught or, being taught, it was lost in the complexities and uncertain priorities of a hormone-driven, teenager’s mind.

As a referee between the perspectives of Upton Sinclair, Ray Stannard Baker and J. Ogden Armour I referred to what I consider one of the greatest single works of American History: Mark Sullivan’s Our Times. His section on “The Crusade for Pure Food” is an amazing read that cuts across all of this information and provides a cohesive believable historical timeline [too much to be presented here]. In a footnote, he positions the works of Upton Sinclair and Ray Stannard Baker of McClure’s Magazine.

The following footnote to history is a long read but well worth the insight for those who, like me, just remember The Jungle’s significance from a multiple-choice test with no context that was either never taught or, being taught, it was lost in the complexities and uncertain priorities of a hormone-driven, teenager’s mind.

In order that the reader of this volume may escape the error, practically universal, of classifying Sinclair and his Jungle with the “Muckrakers” who made much history during this period, it should be understood that The Jungle was a novel, fiction; and that these charges about conditions in the stockyards did not purport to have any more than the loose standard of accuracy that fiction demands for local color and background. Moreover, Sinclair as artist was so submerged by Sinclair as propagandist, that accuracy about background was even less compelling on him than on artists who are artists wholly.

As fiction, the charges in The Jungle are to be taken as faithful to the broad picture, the impression. Sinclair gave many of them as portions of the offhand conversation of stock-yard workers among themselves. He did not pretend to have seen these things, nor to have verified them, nor to have taken them from official records. There was truth in them, but not necessarily literal truth.

The “Muckrakers”—Lincoln Steffens, Miss Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker [who wrote the articles I refer to above], and others—were utterly different from Sinclair in their methods. They put out their product as fact and asked the public to accept it and test it as such. The Muckrakers spent months of investigation before printing a brief article of five or six thousand words [“brief” for their day … “unbearably long” for today’s attention deficit readers]. They investigated everything, confirmed everything. (Samuel S. McClure, who was editor of McClure’s Magazine when that periodical was the pioneer and the best of the muckraking publications, verifies my own recollection that a single magazine article by Lincoln Steffens or Miss Tarbell often represented six months of investigation and upward of three thousand dollars of expense, aside from the writer’s salary.)

The Muckrakers took their material from what they themselves saw, or from sworn testimony in lawsuits or in legislative investigations. They made it a point to talk with everybody who had important, first-hand information. Almost always they discussed their material with the man accused, or the head of the corporation they were investigating. Since most of the articles and books written by the Muckrakers would have been libelous if incorrect, the manuscripts were almost always subjected to scrutiny by lawyers.

The fictional character of Sinclair’s Jungle bothered President Roosevelt when he came to use it as the basis of a demand for pure-food legislation. While there was abundant truth in The Jungle (and more in some conditions Sinclair did not mention) to justify the legislation, it was embarrassing to be unable to find proof for some details of Sinclair’s charges.

For the public, the impressionistic impression, so to speak, that Sinclair conveyed was as much as was needed; the public made no meticulous inquiry into details but sensed strongly that there was something rotten in Packingtown, literally.

Mark Sullivan, Our Times

Of course, even after doing months of investigative work a person may still be biased in their perspective and in their presentation of the material. As I have learned, rereading my works, my bias is sometimes revealed in the usage of a single adjective. Sometimes, I struggle for hours over a single word’s removal or change to convey an idea without a bias. It is most difficult.

For me, much of this story comes down to the question of, “Do the ends justify the means.”

J. Ogden Armour is a fine book that focuses on “the ends” that were achieved in the United States of America through the centralization, modernization and usage of new technologies (the refrigerated private-car and investments in research and development of new animal byproducts). Little did I know how massive and important the meat and its byproducts industry was to our early history, dwarfing the steel, copper and breadstuff industries. It is also easy to understand how this centralization brought wealth to the farmers and ranchers of the west and higher degrees of sanitation for the American people in general.

For me, much of this story comes down to the question of, “Do the ends justify the means.”

J. Ogden Armour is a fine book that focuses on “the ends” that were achieved in the United States of America through the centralization, modernization and usage of new technologies (the refrigerated private-car and investments in research and development of new animal byproducts). Little did I know how massive and important the meat and its byproducts industry was to our early history, dwarfing the steel, copper and breadstuff industries. It is also easy to understand how this centralization brought wealth to the farmers and ranchers of the west and higher degrees of sanitation for the American people in general.

|

Maybe it could have been accomplished another way, but it is hard to see how, even now, looking back after more than a century. At the time, even though our republic was founded on a loose coupling of geographic territories, few businessmen seemed to believe there was true power in decentralization (Henry Ford and Alfred P. Sloan Jr. being two of the earliest advocates I have discovered). The case Mr. Ogden weaves so early in the founding of a new industry is a convincing one.

|

|

In the end, I applaud J. Ogden Armour for the purpose behind this book. He told his side of the story—the packers’ story. As many of the reviews of the book of the time recorded, Americans wanted to hear both sides. There is much credibility in both. In this case, personal brand matters and Ray Stannard Baker’s brand, for me, carries more weight and believability.

From what I can determine studying early American Capitalism, corporations were still in their early development and did not “open their books up” for inspection. |

The policy of “openness” came later with men like Judge Gary of the Steel Corporation as he attempted to work with Roosevelt and the country to prove that there could be such things as “good trusts.” His practices enabled the U. S. Steel Corporation to win its anti-trust suit in the Supreme Court.

This is a standard we have come to expect today with the changes implemented almost four decades later during the Great Depression: with further legislation in 1934–1935. Let’s close this review with his stated purpose, that I believe Mr. Ogden accomplished.

“The writing of the articles which have appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, and which forms the basis of this book, was undertaken with great reluctance. First, because of an entire lack of any disposition to thrust my views regarding any subject upon the public; second, because I was equally undisposed to assume to speak for anybody but myself. On the other hand, I could not deny the existence in the public mind of a feeling that the traditional corporation policy of silence under attack is sometimes a tacit confession to the truthfulness of the charges. …

“Finding myself the responsible head of a business founded by a father who had put into its upbuilding the best energies of a long, active life and a very considerable genius for affairs, found it increasingly difficult to keep silent … knowing those attacks to be unfair, unjust, untrue, and in most cases maliciously bitter. …

“I realized more keenly than ever how much more appropriately such an appeal to the common sense of the American people would be if made by my father … However, this being impossible, I put aside my own unwillingness, believing such a course to be dictated by my duty to the interests directly entrusted to my care, to the packing and private-car line industries in general, and finally to the American people.”

Although not as open as I would have liked Mr. Armour to be but, possibly, more open than the times required, it was a beginning that some truly great men followed. Men like Judge Elbert H. Gary of U. S. Steel Corporation, Alfred P. Sloan Jr. of General Motors Corporation, Gerard Swope and Owen D. Young of General Electric, and Henry Firestone of the Firestone Company.

Merryle Stanley Rukeyser made the following observation of Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM:

“The writing of the articles which have appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, and which forms the basis of this book, was undertaken with great reluctance. First, because of an entire lack of any disposition to thrust my views regarding any subject upon the public; second, because I was equally undisposed to assume to speak for anybody but myself. On the other hand, I could not deny the existence in the public mind of a feeling that the traditional corporation policy of silence under attack is sometimes a tacit confession to the truthfulness of the charges. …

“Finding myself the responsible head of a business founded by a father who had put into its upbuilding the best energies of a long, active life and a very considerable genius for affairs, found it increasingly difficult to keep silent … knowing those attacks to be unfair, unjust, untrue, and in most cases maliciously bitter. …

“I realized more keenly than ever how much more appropriately such an appeal to the common sense of the American people would be if made by my father … However, this being impossible, I put aside my own unwillingness, believing such a course to be dictated by my duty to the interests directly entrusted to my care, to the packing and private-car line industries in general, and finally to the American people.”

Although not as open as I would have liked Mr. Armour to be but, possibly, more open than the times required, it was a beginning that some truly great men followed. Men like Judge Elbert H. Gary of U. S. Steel Corporation, Alfred P. Sloan Jr. of General Motors Corporation, Gerard Swope and Owen D. Young of General Electric, and Henry Firestone of the Firestone Company.

Merryle Stanley Rukeyser made the following observation of Thomas J. Watson Sr., the traditional founder of IBM:

Watson insisted on sharing prosperity with employees, not only in wages and hours, but also in collateral fringe benefits, including cultural and leisure facilities. Watson knew that, unless he went out of his way to show that a big enterprise could be humane and considerate, it would become a psychological symbol of oppression and exploitation.

Merryle Stanley Rukeyser, “The Economic Outlook,” Kingsport News, June 26, 1956

It took time for the leading industrialists of the mid-20th Century to understand this quite simple concept. Hopefully, those who are leading in the early 21st Century won’t have to “relearn” this basic fundamental truth as expressed in the following written by Edmund Burke.

Ray Stannard Baker opened one of the railroad articles mentioned above with it.

Ray Stannard Baker opened one of the railroad articles mentioned above with it.

Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere. And the less of it there is within, the more there must be without.

In Stannard's book, he offers this insight that is as poignant as they come:

He [J. Ogden Armour], too, I thought, was a sort of slave to industry, with no union to protect him. In short, there he was, held in his place on the wheel as firmly as any Polish butcher who knifed hogs in the Armour packing house.

Amen, Edmund Burke and Baker!

Entrepreneurial lessons?

Cheers,

- Pete

Entrepreneurial lessons?

Cheers,

- Pete