Lou Gerstner wrote, "People truly do what you inspect, not what you expect." … Lest we forget, these "inspection pages" exist because chief executives are "people" too.

Evaluating Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty's Performance

- The Corporation Ginni Inherited

- The Bag Ginni Was Left Holding

- Examining the Bag for Contents and Context

- Profit and Revenue Growth with a Revenue Growth Trendline

- Evaluating Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty's Performance

- The Corporation Needed a Salesperson-in-Chief

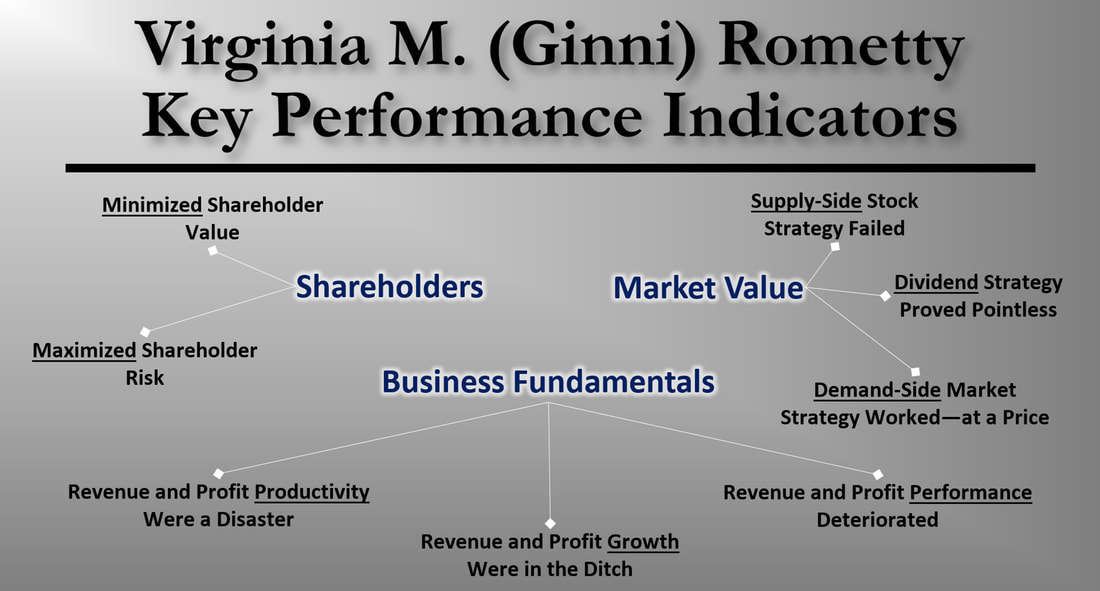

- A Few Key Performance Indicators Shareholders Should Consider

- Virginia M. Rometty's Results for Eight Critical KPIs

The Corporation Ginni Inherited

- The Bag Ginni Was Left Holding

It is poor management to evaluate an individual without context. When a salesman takes over a new territory, if that territory only produced 10% of its assigned quota the year before, and the new salesman makes 50% of an unchanged quota, this could be a “4” or a “1” performance. Without context it is hard to know. (A performance rating of a “4” is someone that needs to be thrown a life preserver before they drown, and a “1” is an individual that not only swims independently but occasionally walks on water distributing life preservers.)

So, let’s start with a few facts, not to win the former chief executive any pity points because she was around for these activities, but to set the context.

So, let’s start with a few facts, not to win the former chief executive any pity points because she was around for these activities, but to set the context.

- Examining the Bag for Contents and Context

In 2007, Samuel J. Palmisano decided to run his corporation, not by intelligent, real-time management insights, but by a financial plan. He called this plan, a roadmap. All internal decisions were put on financial autopilot with an earnings-per-share target that overruled management judgement. Employees came to refer to themselves as roadkill in the face of these roadmaps (2007–10 and 2011–15). This plan—although an extreme—was just the logical extension and final empowerment of a pre-existing financial autocracy implemented by Louis V. Gerstner.

As Mr. Palmisano turned the company over to Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty in 2011, he committed the company, the new chief executive, and the employees to a second five-year roadmap.

As Mr. Palmisano turned the company over to Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty in 2011, he committed the company, the new chief executive, and the employees to a second five-year roadmap.

|

Mr. Palmisano also systematized the movement of work that was performed by highly motivated, highly productive and therefore highly paid individuals to lower-wage countries. A long-term analysis has documented that this corporate process called “workload rebalancing” also carries the long-term effect of reducing employee productivity and corporate competitiveness.

Lower wages, less empowerment, and higher centralization has reduced employee enthusiasm, engagement and passion. It became a race between providing the market with quick-hitting, short-term, exaggerated profits, while ignoring the effects of the slower-evolving, inexorable deterioration in employee productivity. Of course, the key to winning this game is in the timing: place your bets and take your winnings off the table before the productivity tortoise catches up with the profit hare. Sam Palmisano also continued his one-upmanship of Lou Gerstner in a share buyback frenzy. Mr. Gerstner averaged $6.3 billion in share repurchases per year; Sam Palmisano averaged $9.9 billion per year. Over seventeen years, it was an amazing investment prioritization of $143 billion into paper instead of into the business’ people, processes, and products. |

As is apparent from the sidebar provided, Harvey Firestone, of Firestone Tire Company, would not have implemented roadmaps because he understood where the rubber meets the road: Executives should operate a business, not execute a plan. Many of our early American Industrialists agreed with Harvey.

Both Lou Gerstner and Sam Palmisano partially funded these stock buybacks by extracting value from their hundred-year-old corporation – one proof point: employees’ pension plans around the world.

- Profit and Revenue Growth with a Revenue Growth Trendline

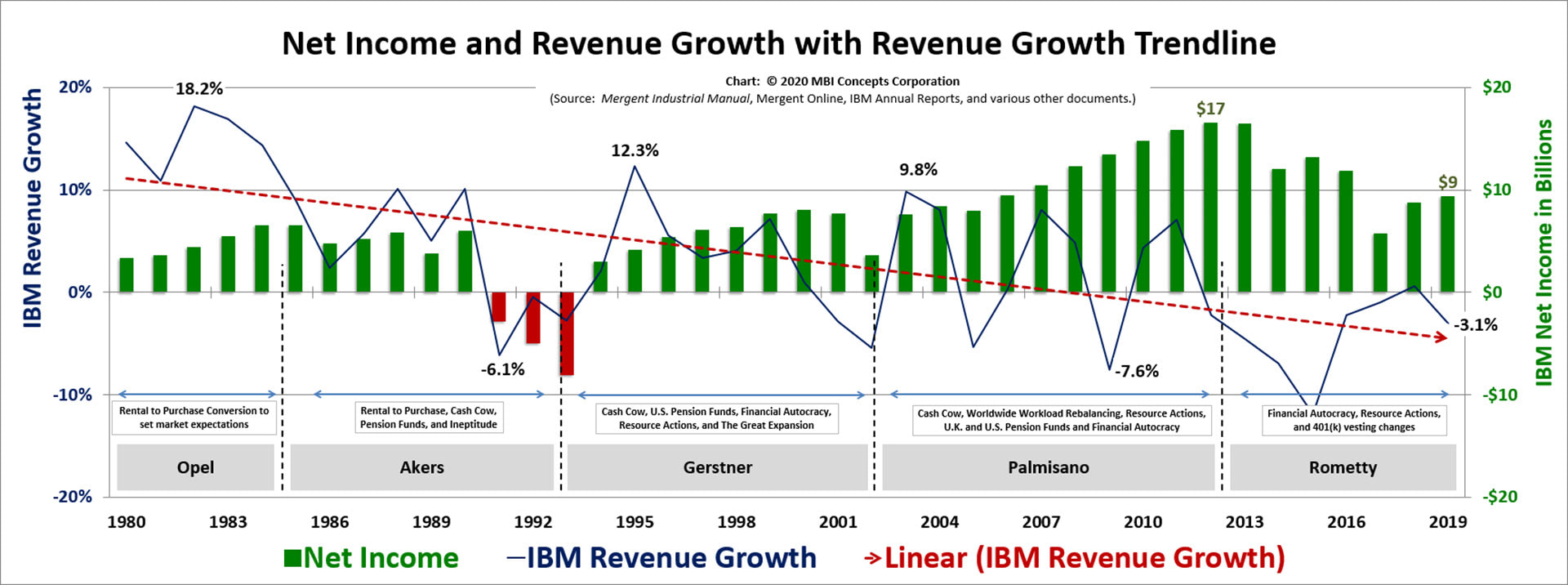

IBM had been having its value extracted for decades.

The trend line above documents IBM’s four-decade decline in revenue growth.

In the mid-’80s, John Opel set a growth expectation in the market place such that the press wrote about “The $100 Billion IBM by 1990” and “The $180 Billion IBM by 1994.” Laughable? Today, yes! Most analysts at the time believed his financially engineered results. They didn’t understand IBM enough to comprehend the big picture: the chief executive was quite simply pulling in revenue and profits from the out years by selling off the company’s leased hardware base, and then talking big about the results. It seems that when chief executives “talk big” markets move, and the shareholders, who were a little slow on the uptake, bought into the story until 1993 when—in a single year—a third of them sold their stock.

Of course, this downward trend in revenue growth could be the result of the difficulty of driving a higher growth percentage on an ever-larger revenue base. Although Watson Jr. proved differently during his time as chief executive, growth numbers may be subject to diminishing returns. Sometimes there are no conspiracies, just simple explanations. That is why after showing the shareholders their returns on a quarter of a trillion-dollar investment, we will continue Virginia M. Rometty’s evaluation with productivity numbers—specifically, revenue per employee and net income per employee.

Tracking employee productivity determines if a chief executive and her board are adding to the wealth of a corporation or feeding off it, maintaining the status quo or losing control. Mrs. Rometty’s most fundamental choice in 2012, as she became IBM’s Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer, was between being her own chief executive or being more of the same. She chose the latter.

Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty never understood that the individuals in her salesforce who gave their customers one hundred percent could carry only twenty-five percent of the burden. They needed a chief executive officer who, as a saleswoman-in-chief, could build an organization to provide the other seventy-five percent that makes selling possible.

In the mid-’80s, John Opel set a growth expectation in the market place such that the press wrote about “The $100 Billion IBM by 1990” and “The $180 Billion IBM by 1994.” Laughable? Today, yes! Most analysts at the time believed his financially engineered results. They didn’t understand IBM enough to comprehend the big picture: the chief executive was quite simply pulling in revenue and profits from the out years by selling off the company’s leased hardware base, and then talking big about the results. It seems that when chief executives “talk big” markets move, and the shareholders, who were a little slow on the uptake, bought into the story until 1993 when—in a single year—a third of them sold their stock.

Of course, this downward trend in revenue growth could be the result of the difficulty of driving a higher growth percentage on an ever-larger revenue base. Although Watson Jr. proved differently during his time as chief executive, growth numbers may be subject to diminishing returns. Sometimes there are no conspiracies, just simple explanations. That is why after showing the shareholders their returns on a quarter of a trillion-dollar investment, we will continue Virginia M. Rometty’s evaluation with productivity numbers—specifically, revenue per employee and net income per employee.

Tracking employee productivity determines if a chief executive and her board are adding to the wealth of a corporation or feeding off it, maintaining the status quo or losing control. Mrs. Rometty’s most fundamental choice in 2012, as she became IBM’s Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer, was between being her own chief executive or being more of the same. She chose the latter.

Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty never understood that the individuals in her salesforce who gave their customers one hundred percent could carry only twenty-five percent of the burden. They needed a chief executive officer who, as a saleswoman-in-chief, could build an organization to provide the other seventy-five percent that makes selling possible.

Evaluating Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty's Performance

- The Corporation Needed a Salesperson-in-Chief

There will be little doubt after reviewing the detailed data that Ginni Rometty’s tenure is not that of a chief executive presiding over a difficult transition—some have compared her to a captain turning a battleship. Instead, she disregarded all the warning signs of imminent disaster—more comparable to a destroyer’s commander who maintains course and speed while headed towards an iceberg.

In those areas where the law requires transparency, her record is as follows: year-over-year revenue growth was negative and profit growth was, at best, erratic; sales productivity was down 12% and profit productivity was down 28%; revenues were down 28% and profit was down 41%; and the company lost almost half of its market value—44%.

Employee engagement and customer satisfaction, two areas where ethics demands transparency, but the law does not, were, at a minimum, unmentionably low and most likely uncompetitive. Even as executives spent more money on share repurchases, employees waved off the opportunity to purchase their corporation’s shares at a discount.

Warren Buffett invested, took a look around, and left. Shareholders who stuck around lost money and saw risk rise astronomically. Strong, high-performing employees lost employment, and profitable, loyal customers lost a trusted vendor. Supportive societies that had sheltered the company for more than eight decades suffered from economic disinvestment as the company invested in paper instead of in people, processes, and products.

In those areas where the law requires transparency, her record is as follows: year-over-year revenue growth was negative and profit growth was, at best, erratic; sales productivity was down 12% and profit productivity was down 28%; revenues were down 28% and profit was down 41%; and the company lost almost half of its market value—44%.

Employee engagement and customer satisfaction, two areas where ethics demands transparency, but the law does not, were, at a minimum, unmentionably low and most likely uncompetitive. Even as executives spent more money on share repurchases, employees waved off the opportunity to purchase their corporation’s shares at a discount.

Warren Buffett invested, took a look around, and left. Shareholders who stuck around lost money and saw risk rise astronomically. Strong, high-performing employees lost employment, and profitable, loyal customers lost a trusted vendor. Supportive societies that had sheltered the company for more than eight decades suffered from economic disinvestment as the company invested in paper instead of in people, processes, and products.

|

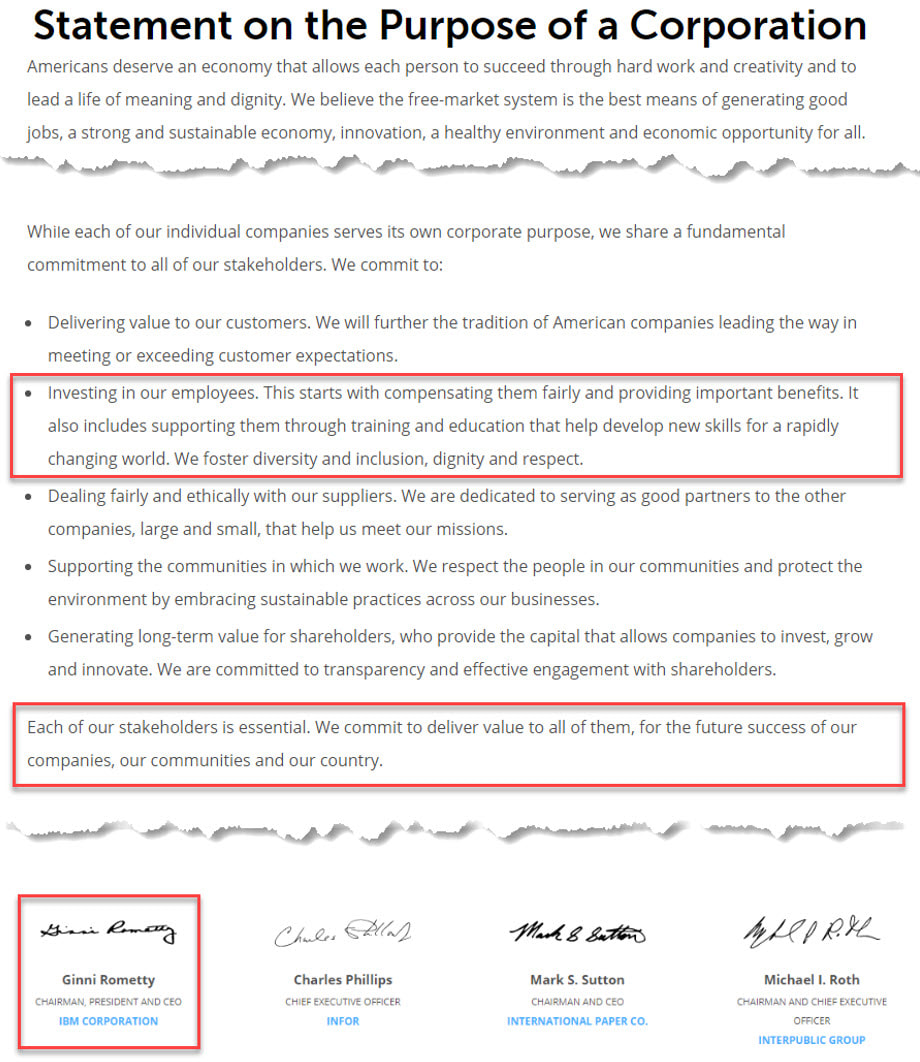

Even though Ginni Rometty signed the document to the right, she never invested properly to build a stable, self-sustaining stakeholder ecosystem:

|

- A Few Key Performance Indicators Shareholders Should Consider

The first few decades of the twenty-first century have been sold as the sovereign domain of shareholders. Many interpret this to mean that shareholder returns should be, can be, or—some even imply through their actions—can only be maximized at the expense of the other corporate stakeholders. This is a fallacy of thought which the greatest industrialists of early 20th Century America took exception to in their corporate policies. The early industrialists that built the foundation upon which the United States rests today, understood the necessity that their economic system supported a self-sustaining stakeholder ecosystem.

An evaluation of the history of IBM confirms that shareholder primacy is a strategic impossibility to maximize long-term corporate results. The performance information that is presented on this site, is extracted from THINK Again!: IBM CAN Maximize Shareholder Value – The Rometty Edition. It should dispel any notion that IBM’s shareholders have benefited from the corporation’s lack of focus on its customers, employees, and the stakeholders’ shared societies. Over the last two decades but especially over the last eight years with Rometty, shareholders have suffered in kind with all other stakeholders.

It is unlikely that Ginni Rometty (or the board of directors) ever saw the charts that are presented here reflecting her performance in her eight years in the corner office. She surrounded herself with individuals who were replicas of each other in one significant way: to their core they were yes-men and -women, and this expectation filtered down into every level of the organization. Even first-line managers have become little more than cat’s-paws for the human resource organization’s implementation of workload rebalancing. No one publicly challenges the supremacy of the corporation’s financial goals or its chosen way to achieve its ends. [See Footnote #1]

In a new century that has been all about the supremacy of the shareholder—IBM shareholders did not prosper over the last eight years. Will investors prosper in the coming years? No one knows, but it will be an uphill battle if the past is an educational tool to evaluate the corporation’s present course and speed. Are there major icebergs in its path? This author believes that IBM’s history indicates that there are, and it needs major course corrections in its investment strategies to stop its growing 21st Century irrelevance.

Let's leave you with a thought from the past:

An evaluation of the history of IBM confirms that shareholder primacy is a strategic impossibility to maximize long-term corporate results. The performance information that is presented on this site, is extracted from THINK Again!: IBM CAN Maximize Shareholder Value – The Rometty Edition. It should dispel any notion that IBM’s shareholders have benefited from the corporation’s lack of focus on its customers, employees, and the stakeholders’ shared societies. Over the last two decades but especially over the last eight years with Rometty, shareholders have suffered in kind with all other stakeholders.

It is unlikely that Ginni Rometty (or the board of directors) ever saw the charts that are presented here reflecting her performance in her eight years in the corner office. She surrounded herself with individuals who were replicas of each other in one significant way: to their core they were yes-men and -women, and this expectation filtered down into every level of the organization. Even first-line managers have become little more than cat’s-paws for the human resource organization’s implementation of workload rebalancing. No one publicly challenges the supremacy of the corporation’s financial goals or its chosen way to achieve its ends. [See Footnote #1]

In a new century that has been all about the supremacy of the shareholder—IBM shareholders did not prosper over the last eight years. Will investors prosper in the coming years? No one knows, but it will be an uphill battle if the past is an educational tool to evaluate the corporation’s present course and speed. Are there major icebergs in its path? This author believes that IBM’s history indicates that there are, and it needs major course corrections in its investment strategies to stop its growing 21st Century irrelevance.

Let's leave you with a thought from the past:

Wealth can no more be safely created and permanently held by the mere shuffling of securities, than character can be created by shuffling cards.

John Wanamaker, Golden Jubilee, 1911

Maybe we need more character in our chief executives if we are to create more dependable societal wealth.

Cheers,

- Pete

- Pete

Here are Ginni's results.

Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty's Results for Eight Critical KPIs

|

Shareholder Key Performance Indicators |

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #1:

|

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #2:

|

|

Market Value Key Performance Indicators |

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #3:

|

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #4:

|

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #5:

|

|

Business Fundamentals Key Performance Indicators |

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #6:

|

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #7:

|

|

Questions answered by key performance indicator (KPI) #8:

|

|

[Footnote #1]: “Cat’s-paw” is a fascinating legal term used in a document signed December 20, 2019, by Judge Andrew W. Austin, United States magistrate judge in the case of Jonathan Langley vs. International Business Machines Corporation.

The legal system recognizes that an employee may experience discriminatory intent, not necessarily at the hands of the alleged decision maker—who may have acted without any age-based animus, but instead, from a person who was acting as the “cat’s-paw” for an entity—who did have a discriminatory intent. |

This term, extracted from Aesop’s fable of “The Monkey and the Cat,” is much more interesting and descriptive than just calling IBM’s first-line management what it has become: pawns—individuals who are manipulated by human resources to achieve the distorted financial ends of the corporation no matter the human cost. This age discrimination case was settled out of court in early 2020 by “joint stipulation,” and it is surmised that IBM paid to avoid an embarrassing discovery process that had become almost unavoidable otherwise.

Just like every other state, Texas has its good and bad judges. Judge Andrew W. Austin is one of the good ones.

Just like every other state, Texas has its good and bad judges. Judge Andrew W. Austin is one of the good ones.