A Study of "William Cooper Procter: Businessman"

|

|

Date Published: June 24, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

Much of this material is the intertwining of two different perspectives on William Cooper Procter: one presents the man as seen through his personal letters over a period of twenty-seven years (from 1907 through 1934) to his niece Mary E. Johnston, and one is a summation of Mr. Procter’s business career at Procter & Gamble by his successor Richard R. Deupree.

It is also supported by additional research into the workings of Procter & Gamble Company gathered from A. W. Shaw’s, System: The Magazine of Business.

Enjoy!

It is also supported by additional research into the workings of Procter & Gamble Company gathered from A. W. Shaw’s, System: The Magazine of Business.

Enjoy!

Introduction

|

Combining Business and Personal Insights of Richard Dupree and Mary Johnston, respectively |

|

Much of this material is the intertwining of two different perspectives on William Cooper Procter: one presents the man as seen through his letters over a period of twenty-seven years (from 1907 through 1934) to his niece Mary E. Johnston, and one is a summation of Mr. Procter’s career at Procter & Gamble by his successor Richard R. Deupree. It is also supported by material concerning the workings of Procter & Gamble from A. W. Shaw’s System: The Magazine of Business.

Mr. Deupree was a long-term employee of Procter & Gamble and can be considered a credible evaluator of Mr. Procter. He was the fourth chief executive of Procter & Gamble and its first chief executive without the Procter surname: (1) William Procter (founder), (2) William A. Procter (son), (3) William “Cooper” Procter (grandson), and (4) Richard R. Deupree.

In America’s Fifty Foremost Business Leaders, B. C. Forbes described Mr. Dupree as “a ‘man of the people,’ with no trace of ‘stuffed-shirtishness’ to his personality.” That comes across in his presentation to The Newcomen Society of England concerning Mr. Procter. |

|

The humanness of “Cooper” Procter comes through in The Letters of William Cooper Procter. Even the tensions of the age come through, such as the growing women’s movement.

His niece takes him to task over his opposition to married women being employed outside of their homes. She writes to him that such a belief was of “Stone Age Mentality.” Maybe not “Stone Age,” but surely a belief that was quickly changing beneath his feet as he wrote the words.

At one point he writes of the suffragette movement, “While I am opposed to women suffrage, I believe it is coming, and it is hardly worthwhile fighting only to delay it.” This is an openness extracted from a personal interaction—between two individuals who cared about each other—and not an autobiography cleaned up to put forward the best image of a man decades after his passing. |

Before getting upset, we all have to look at our fathers/mothers and grandfathers/grandmothers and remember that although our environment may change quickly, human nature evolves over centuries or eons. … Our goal should be that each succeeding generation always moves forward a little, rarely stands still and never regresses.

Although he was not supportive of the suffragette movement, he did not believe in standing in its way either. I am sure that this movement caused many family disputes around the country, but it is obvious that while the niece and uncle disagreed, they still loved and kept up personal communications with each other—which many times were blunt.

|

And although he stood aside on this one issue, from all the material presented he did not stand aside when it came to the welfare of his company, customers, shareholders, or employees—who at the time included unmarried women.

His policies benefited all his stakeholders—men and women—equally. This chief executive focused on supporting this social community to build a successful, resilient company. So, after a few quotes concerning Mr. Procter from his successor—Richard Deupree, let’s start with Mr. Procter's focus on the primary stakeholder every business should consider first …

… its customers.

|

Women working at P. & G. in 1915

|

The Business Life of "William Cooper Procter: Industrial Statesman"

- Quotes of the Successor—Richard R. Deupree, on William C. Procter

- William C Procter's Focus on Stakeholders

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

Quotes of the Successor—Richard R. Deupree, on William C. Procter

On Changing Products as Needed

“New methods of illumination reduced the need for candles [P&G's main source of income], while improved sanitation, and the introduction of plumbing increased the demand for soap. In 1883, William Cooper Procter’s first year as an employee, the company launched a nationwide advertising campaign to promote the sale of Ivory Soap. … with the slogan, ‘It Floats’”

On Research and Development in 1870

“A long-established tradition of Procter & Gamble was … high quality, consistently maintained; … widespread advertising of products under brand names … emphasizing the importance of quality; … [and] as early as the seventies [1870s] a corner of the factory’s machine shop had been partitioned off for the use of a chemist.” *

“New methods of illumination reduced the need for candles [P&G's main source of income], while improved sanitation, and the introduction of plumbing increased the demand for soap. In 1883, William Cooper Procter’s first year as an employee, the company launched a nationwide advertising campaign to promote the sale of Ivory Soap. … with the slogan, ‘It Floats’”

On Research and Development in 1870

“A long-established tradition of Procter & Gamble was … high quality, consistently maintained; … widespread advertising of products under brand names … emphasizing the importance of quality; … [and] as early as the seventies [1870s] a corner of the factory’s machine shop had been partitioned off for the use of a chemist.” *

Richard R. Deupree, 1951

The Newcomen Society of England

William Cooper Procter: Industrial Statesman

The Newcomen Society of England

William Cooper Procter: Industrial Statesman

* Editor's note: Several early industrialists saw a need for and invested in research and development.

William C. Procter's Focus on Stakeholders

|

A Focus on the Customer |

|

Over one hundred and thirty years ago, on October 6, 1887, Mr. Procter presented his employees with their first profit sharing payment. It was coined the “Dividend Day Speech,” and it started a semi-annual company tradition that, in many ways, appears quite similar to IBM’s Family Days.

In his speech, he went straight to the point: without customers there could be no profits to share. “The first job we have is to turn out quality merchandise that consumers will buy and keep on buying. If we produce it efficiently and economically, we will earn a profit, in which you will share. "But profits can’t be distributed unless they are earned. And if the company is to take care of its equipment, expand normally, and remain in a sound financial position, part of the earnings must be plowed back into the business. “That will safeguard your future, as well as the company’s.” |

William Cooper Procter, “William Cooper Procter: Industrial Statesman”

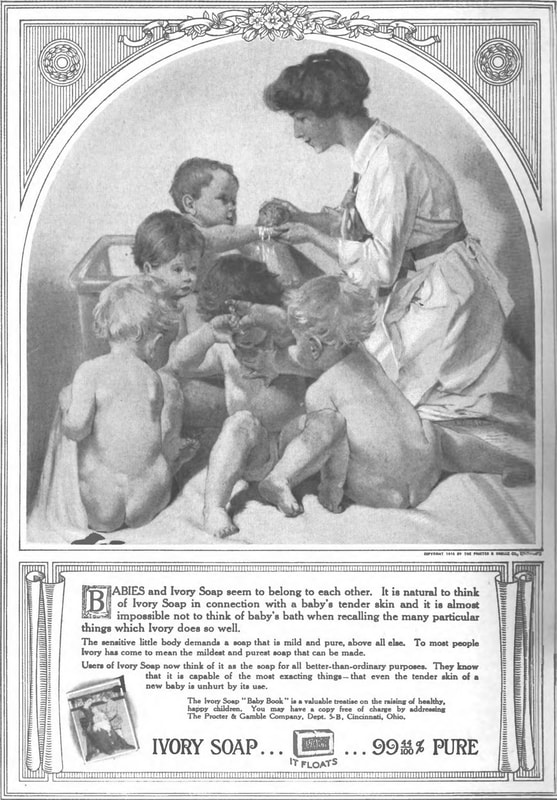

Ivory Soap was the product that put Procter & Gamble on the business map. As the electric light spread across the country, this product’s revenue transitioned the corporation from its dependency on candle revenue to soap and other oil/fat byproducts (Crisco being its next big hit).

The corporation focused on the customer, and before branding became a marketing discipline, Ivory Soap was one of America’s first and strongest consumer brands: As seen in the advertisement from 1915, Ivory Soap was a product that was 99 44/100 percent pure, “It Floats,” and was safe enough to use on children.

The corporation focused on the customer, and before branding became a marketing discipline, Ivory Soap was one of America’s first and strongest consumer brands: As seen in the advertisement from 1915, Ivory Soap was a product that was 99 44/100 percent pure, “It Floats,” and was safe enough to use on children.

Maybe by understanding this, it is easier to acknowledge why Mr. Procter showed only “incidental concern” for the passage of the Food and Drug Act by Teddy Roosevelt in 1906. He was already applying the “intent of the law” within his own company.

Although other corporations needed government oversight, his did not, because …

Although other corporations needed government oversight, his did not, because …

… this chief executive understood the value of a trusted brand.

|

A Concern for Shareholders |

It is rare to get a clear glimpse into the thoughts an ethical chief executive, but it seems that difficult times like the Recession of 1920–21 can be personality unmasking events. In September 1922, Mr. Procter thought he saw a light at the end of this recession’s economic tunnel:

“I think everything is working out all right, but the business and organization was in bad shape two or three years ago. … I had the burden of protecting the livelihood of many people and was always conscious of it [emphasis added]. I have been accused of all kinds of selfishness and hardness without being able to reply, when as a matter of fact, my fault has been just the opposite.

“I had no personal benefit or interest to gain; my outside investments being ample—even if Procter & Gamble met disaster. I considered the interests and feelings of others longer than I should have done as I jeopardized the interest of the company in doing so.

“It hurt more than you have any idea during the past few years, but thank heavens, it is behind me.”

“I think everything is working out all right, but the business and organization was in bad shape two or three years ago. … I had the burden of protecting the livelihood of many people and was always conscious of it [emphasis added]. I have been accused of all kinds of selfishness and hardness without being able to reply, when as a matter of fact, my fault has been just the opposite.

“I had no personal benefit or interest to gain; my outside investments being ample—even if Procter & Gamble met disaster. I considered the interests and feelings of others longer than I should have done as I jeopardized the interest of the company in doing so.

“It hurt more than you have any idea during the past few years, but thank heavens, it is behind me.”

William Cooper Procter to Mary E. Johnston, September 30, 1922

Yes, Chief Executive Officers are people with feelings too, and what he thought was behind him—that everything was working out all right—turned out to be not true. William Cooper Procter would continue to face trying times and, with them, supreme questions of ethics.

In the following letter to Miss Johnston, Mr. Procter shows the struggles he had when he believed business conditions warranted the cancellation of dividends moving into January 1923. This was another company, similar to General Motors, General Electric, Firestone Tire Company, and International Business Machines, that felt the effects of the Recession of 1920–21.

In January 1923, he wrote the following to his niece. [To add context, I have taken the liberty of adding additional notes.]:

“The question of the stock dividend has to be answered next July [1923].

“It [the dividend] cannot be continued. … Of course, it is going to adversely affect the value of the stock. Every person is going to be sore and say they were misled. My close friends will be hurt because I did not tell them earlier so they could sell out before the decline. [At this point in stock market history, insider trading was not illegal. It would have been legal for him to warn his friends, and it was an all-to-common practice. Although legal, it violated the ethical mores of many besides Mr. Cooper. Two other chief executives who believed and acted similarly were Thomas J. Watson Sr., IBM President, and Elbert H. Gary, United States Steel Corporation President.]

“My own judgment and prestige will suffer; I cannot help it, and in the long run, the present plan … will work for the advantage of the average stockholder who held his stock as an investment and not as a speculation. … No one can accuse me of unloading my own stock or speculating in it. Notwithstanding all this, however, I know I am going to have a tough time this summer. … It is going to be mean, and I am afraid widespread.

“I wish I could decide on the right thing to do and the best way to put it to the stockholders, for then, I could try to forget it. But now, I must think of it. Therefore, this extra week here [vacationing] is going to be a lifesaver; until I do decide, I cannot talk to any person—not even Herbert French—as it would be unfair to let it leak out so some could take advantage of it at the expense of others [At this time, Mr. Procter was 61 years old].”

In the following letter to Miss Johnston, Mr. Procter shows the struggles he had when he believed business conditions warranted the cancellation of dividends moving into January 1923. This was another company, similar to General Motors, General Electric, Firestone Tire Company, and International Business Machines, that felt the effects of the Recession of 1920–21.

In January 1923, he wrote the following to his niece. [To add context, I have taken the liberty of adding additional notes.]:

“The question of the stock dividend has to be answered next July [1923].

“It [the dividend] cannot be continued. … Of course, it is going to adversely affect the value of the stock. Every person is going to be sore and say they were misled. My close friends will be hurt because I did not tell them earlier so they could sell out before the decline. [At this point in stock market history, insider trading was not illegal. It would have been legal for him to warn his friends, and it was an all-to-common practice. Although legal, it violated the ethical mores of many besides Mr. Cooper. Two other chief executives who believed and acted similarly were Thomas J. Watson Sr., IBM President, and Elbert H. Gary, United States Steel Corporation President.]

“My own judgment and prestige will suffer; I cannot help it, and in the long run, the present plan … will work for the advantage of the average stockholder who held his stock as an investment and not as a speculation. … No one can accuse me of unloading my own stock or speculating in it. Notwithstanding all this, however, I know I am going to have a tough time this summer. … It is going to be mean, and I am afraid widespread.

“I wish I could decide on the right thing to do and the best way to put it to the stockholders, for then, I could try to forget it. But now, I must think of it. Therefore, this extra week here [vacationing] is going to be a lifesaver; until I do decide, I cannot talk to any person—not even Herbert French—as it would be unfair to let it leak out so some could take advantage of it at the expense of others [At this time, Mr. Procter was 61 years old].”

William Cooper Procter, Letter to Mary Johnston, January 1923

Fortunately, the business turned up as sharply as it had turned down, but not until these letters provided a wonderful glimpse into the mind of a concerned chief executive, and his desire to treat his shareholders fairly and uniformly.

Treating shareholders properly wasn’t just a financial concern …

Treating shareholders properly wasn’t just a financial concern …

… it was an ethical issue of his day that he stood above.

|

A Dedication to a Long-Term, Employer–Employee Relationship |

Mr. Procter’s concerns for the welfare of his employees extended well beyond what follows, but his desire to share the profits of his corporation both directly in cash and stocks, and in one leading edge benefit, that was so needed in his day, should suffice for the purposes of reviewing these books.

- Guaranteed Employment

|

In the 20th Century IBM was known for its tradition or practice of full employment.

I have written much on the corporation’s failure to abide by this practice in the 21st Century, and the effect resource actions have on the productivity of the individual which has been reflected in IBM's two-decade-long, macro-level drop in sales and profit productivity. |

Newspaper headline from 1923 concerning P&G.

|

I have also always written that IBM’s full-employment practice was just that … a practice … not a policy. Unlike IBM, William Cooper Procter implemented a full-employment “policy.” He formally announced it, stood by it and practiced it. Understanding the lengths he went to for a policy of “guaranteed employment,” helps define what it takes to implement such a “policy” not just stand by a “practice” or “tradition.”

Mr. Procter wanted to implement guaranteed employment, but he needed to change his company’s selling processes to accomplish this task. He saw the complexities behind the problem clearly and proceeded carefully. He established a Department of Economic Research to study business trends as a basis for long-range planning. He initiated studies: to anticipate demand and to explore the acquisition, shipping and storage of raw materials; to stabilize existing markets while exploring new markets through research and development; and to implement sales quotas that encouraged a continuous, smooth flow of products between his company and his customers through demand-generation advertising.

This was an amazing piece of analysis for a late 19th and early 20th Century industrialist, much of which could not be contained in the short presentation given by Richard Deupree and, as far as I know, has not been documented in detail anywhere. Here are three examples of the internal changes he made:

After, implementing these multiple new policies, Mr. Procter then started an 18 month trial period to “prove the plan,” until on August 1, 1923, Procter & Gamble implemented “Guaranteed Employment.” It promised 48 weeks of full-time work each calendar year to all employees with 6 months of service who also participated in the profit-sharing plan [See Footnote #1].

Mr. Procter discussed the corporation’s achievement of a “straight horizontal line” of employment with the press:

“Five years ago the sales curve showed a series of mountains and gorges. Today, through cooperation between the sales and manufacturing departments, the tops of the peaks on our business curve have been shoveled down to fill up the valleys.

“The shipping curve is a succession of gentle waves; the manufacturing and employment curves are straight horizontal lines.”

Mr. Procter wanted to implement guaranteed employment, but he needed to change his company’s selling processes to accomplish this task. He saw the complexities behind the problem clearly and proceeded carefully. He established a Department of Economic Research to study business trends as a basis for long-range planning. He initiated studies: to anticipate demand and to explore the acquisition, shipping and storage of raw materials; to stabilize existing markets while exploring new markets through research and development; and to implement sales quotas that encouraged a continuous, smooth flow of products between his company and his customers through demand-generation advertising.

This was an amazing piece of analysis for a late 19th and early 20th Century industrialist, much of which could not be contained in the short presentation given by Richard Deupree and, as far as I know, has not been documented in detail anywhere. Here are three examples of the internal changes he made:

- Changes to Direct Selling: Procter & Gamble began selling direct to jobbers (resellers) and retailers. This meant that the corporation could bypass the middleman in many of its transactions who caused the variability in demand as they stocked up or reduced inventory in anticipation of a growing or contracting economy.

- Just-in-Time Inventory: The Recession of 1920–21 was a wake up call for the company. It had built up a supply of high-priced raw materials when the recession hit and in one year wrote off losses equivalent to the total earnings of the previous five years: $30 to $35 million. This led the company to implement a multitude of changes, one being just-in-time inventory. Although, it wouldn’t be called this until the mid-to-late 20th Century, the company implemented a process to ensure that a “shipment of cans” for Crisco arrived just in time to “be filled,” saving on the cost of storage.

- Employees’ Conference Committee: This committee provided for employee representation on the company’s board of directors. Once a year a representative employee from each plant was elected to serve on the board and to attend all official meetings. (This is an excerpt from a press article. Although the Employees' Conference Committee was mentioned in Mr. Deupree's speech, this aspect of the Committee was not highlighted.)

After, implementing these multiple new policies, Mr. Procter then started an 18 month trial period to “prove the plan,” until on August 1, 1923, Procter & Gamble implemented “Guaranteed Employment.” It promised 48 weeks of full-time work each calendar year to all employees with 6 months of service who also participated in the profit-sharing plan [See Footnote #1].

Mr. Procter discussed the corporation’s achievement of a “straight horizontal line” of employment with the press:

“Five years ago the sales curve showed a series of mountains and gorges. Today, through cooperation between the sales and manufacturing departments, the tops of the peaks on our business curve have been shoveled down to fill up the valleys.

“The shipping curve is a succession of gentle waves; the manufacturing and employment curves are straight horizontal lines.”

|

Seven years later, in the very heart of the Great Depression, Mr. Procter called the plan the “most productive move that this successful company has ever made.” …

… William Cooper Procter had implemented a full-employment policy.

- A Philosophy of Shared Profits

Of course, as you read above, profits depend on finding a customer, retaining a customer and selling more to a satisfied customer. This is productive corporate selling which is especially applicable in the consumer market. It isn’t just a sales’ responsibility for this process, but every member of the corporate team. It was with this in mind that Mr. Procter initiated profit sharing within the Procter & Gamble Company in 1887. He told his employees at the first “Dividend Day” that their first job was “to turn out quality merchandise that consumers will buy and keep on buying.” By the time of his death, the corporation had shared profits for more than 43 years. The journey included a few twists and turns because the goal of profit sharing wasn’t just to share money, but to get a return on that money in employee loyalty and encourage employee long-term savings [see sidebar]. |

This Author's Thoughts and Perceptions

Ensuring an Equitable Distribution of Profits Between Stakeholders

During this time Mr. Procter had to balance investments wisely between his stakeholder communities as he transitioned the company from manufacturing soap—almost like it was made in home kettles—to an automated, massive production line with a hundred “kettles,” each one of which was three stories high, heated by steam coils, and filled with 175,000 pounds of fats/oils, caustic soda solution, and salts. He performed a wonderful balancing act over almost five decades. He ensured that profits from employee productivity improvements rose ever upward to meet the investing requirements of the business.

William Cooper Procter then safeguarded the future of his corporation, the products of his customers, the dividends paid to his shareholders, and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of his employees, by …

William Cooper Procter then safeguarded the future of his corporation, the products of his customers, the dividends paid to his shareholders, and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of his employees, by …

… investing in the corporation’s products, processes and people, expanding into new markets, and maintaining a sound financial position.

William Cooper Procter believed in business-first: investing in making people more productive, processes more effective and products more valuable.

His story should be told.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

His story should be told.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

[Footnote #1] At the announcement of the plan, Mr. Procter highlighted two reasons for these criteria: “six months employment for the company to know whether the man is the type of man the company wishes to continue in its service, and the profit-sharing basis as an evidence that the man wishes to become a permanent employee of the company.” He also highlighted the profit-sharing participation rate at the time: “95% of those eligible for profit-sharing are profit-sharers.” [“Employees Guaranteed 48 Weeks Work Yearly,” The Asheville Citizen-Times, February 1, 1931]