NCR 101: The Art of the Corporate Restart

|

|

Date Published: June 8, 2021

Date Modified: June 29, 2024 |

Several of America’s greatest 20th Century industrialists mastered the art of the restart.

Thomas J. Watson Sr., traditional founder of IBM, lived for four years under the threat of imprisonment for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act; his restart founded a corporation that not only required gentlemanly dress on the outside but an employee of unquestionable business integrity on the inside.

George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company, had his moment of awakening looking out over a major distributor’s warehouse full of his company’s spoiled product; his restart, after more than 470 experiments to fix the problem, added a fifth principle to his business rules of engagement: control of the alternative.

This is the story of John H. Patterson's "restart" at the National Cash Register Company (NCR).

Thomas J. Watson Sr., traditional founder of IBM, lived for four years under the threat of imprisonment for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act; his restart founded a corporation that not only required gentlemanly dress on the outside but an employee of unquestionable business integrity on the inside.

George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company, had his moment of awakening looking out over a major distributor’s warehouse full of his company’s spoiled product; his restart, after more than 470 experiments to fix the problem, added a fifth principle to his business rules of engagement: control of the alternative.

This is the story of John H. Patterson's "restart" at the National Cash Register Company (NCR).

NCR 101: The Art of the Restart

- Never Blindly Follow the Crowd

- A Failure Is an Opportunity to Succeed

- Getting a New Perspective Helps

- Some Will Call It Crazy

- Authors Opinion: Restarting Corporate America

Never Blindly Follow the Crowd

|

John H. Patterson, founder of the National Cash Register Corporation (NCR), had his restart moment too. When he started the NCR Corporation, he viewed his workers like many of the industrialists of his day. He believed that people were to be hired at the “lowest possible wage, worked as hard as they could be worked, and then fired when anyone felt like firing them.”

These labor practices brought him to the edge of corporate failure. He erected a monument of scrap metal to this mistaken belief and posted signs in his factories of only two words to declare the lesson learned: “It Pays.” It is an object lesson as applicable today as it was then. |

John H. Patterson - Wikimedia

|

A Failure Is an Opportunity to Succeed

NCR had just shipped its first large international export of cash registers to England. The necessary changes were made to transition the machines from counting dollars and cents to tracking pounds and pennies. They were to be an extraordinary overseas testament to the benefits of the cash register: reduce theft and provide business owners with more control over their cash. But the registers failed to add properly—a major failing in a high-powered adding machine. Overseas sales clerks were accused of theft and fired. Store owners lost control of their money, and because of poor workmanship, Patterson’s machines came home. With his usual flair for the dramatic, he amassed the useless machines in a pile and enclosed them within a locked, glass enclosure as a memorial “for all time.”

It was a monument of junk dedicated to preventing another business failure.

It was a monument of junk dedicated to preventing another business failure.

Getting a New Perspective Helps

At the time, he did not know what the problem was, but he knew he needed to see things differently. He meant to face his corporation’s problems head-on. He moved his desk out of the corner office and placed it on the factory floor. With this new perspective, he immediately saw the problem: the factory was no fit place to work. His factory took the heart out of a man.

Samuel Crowther writes that what happened next gave rise to the modern-day factory floor—a place where human beings worked in comfort and with self-respect to produce products through the highest of efficiencies.

Samuel Crowther writes that what happened next gave rise to the modern-day factory floor—a place where human beings worked in comfort and with self-respect to produce products through the highest of efficiencies.

Observing and Listening Are the First Steps

|

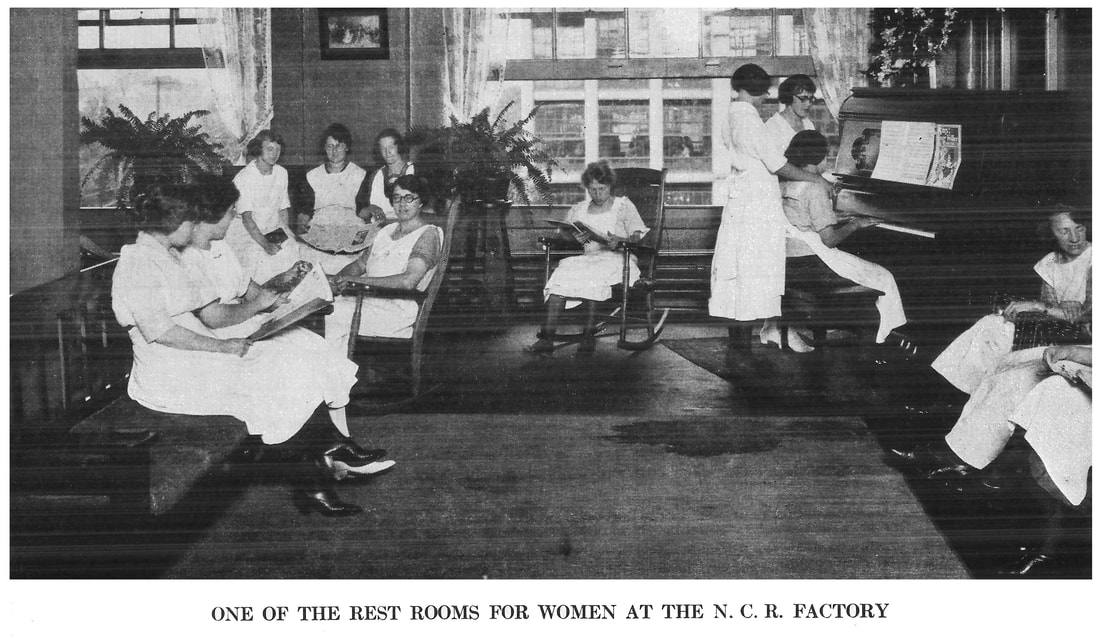

John H. Patterson implemented "rest" rooms for women

|

From his new vantage point, Patterson resolved daily problems in his characteristic flamboyant style: one man commented that the place was too dirty—that night the factory was cleaned inside and out; one night-worker grumbled that, unlike the day shift, the night shift had to wash in dirty water—the chief executive stayed all night overseeing the installation of new wash basins; one man complained that the foremen had lockers while the employees did not—the company installed lockers for all its workers.

|

Patterson then built “rest” rooms and arranged for the employees to take two baths a week on company time because their homes had no bathing facilities; he installed a lunch room so people could eat in peace instead of in the midst of the ever-pounding machinery; he replaced stools with chairs for back support.

Some Will Call It Crazy

Although architects said it was structurally impossible, he built his new factory with more exterior glass than any of its day because he believed men and women would work better in light than in the dark. Finally, even though he wasn’t making money at the time, he raised wages. As a result, his peers chided him and called him a fool. They deemed him crazy. To which he commented:

“ It is an epithet which I prize highly, for I take it as a compliment to a vision that is denied to many unfortunates. … There are advantages in being crazy!”

[Henry Ford was also "crazy." Read about it: here]

John Patterson hung signs in his factories that proclaimed, “It Pays.” His employees knew what the sign meant: it was simple business math to invest three cents in a free lunch and clean bathrooms to get back five cents’ worth of work. It was a change that had a factory-, nation-, and world-wide effect; because it did pay.

Sometimes—to become a great leader, an individual must move their "desk" out of the corner office onto the "shop floor" to discover what “it” may be.

Peter F. Drucker, long after this slice-of-life story named the process "Management by Wandering Around" (MBWA).

Just do it!

“ It is an epithet which I prize highly, for I take it as a compliment to a vision that is denied to many unfortunates. … There are advantages in being crazy!”

[Henry Ford was also "crazy." Read about it: here]

John Patterson hung signs in his factories that proclaimed, “It Pays.” His employees knew what the sign meant: it was simple business math to invest three cents in a free lunch and clean bathrooms to get back five cents’ worth of work. It was a change that had a factory-, nation-, and world-wide effect; because it did pay.

Sometimes—to become a great leader, an individual must move their "desk" out of the corner office onto the "shop floor" to discover what “it” may be.

Peter F. Drucker, long after this slice-of-life story named the process "Management by Wandering Around" (MBWA).

Just do it!

Author's Opinion: Restarting Corporate America

The citizens of the United States of America are fortunate that working conditions have moved beyond what John Patterson found on his factory floor in the late 19th Century. Workplaces are expected to be safe and clean.

|

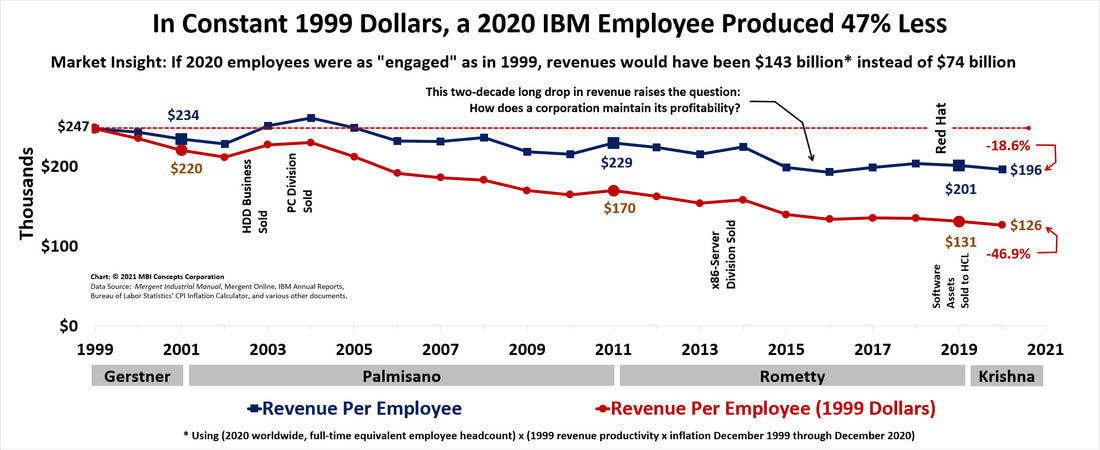

Americans no longer need a workplace benefit to maintain personal hygiene, but too many American corporations view their knowledge workers as interchangeable cogs in a giant, corporate-process machine with so little value that they can be swapped out without consideration of the long-term costs—a continual drop in revenue and profit productivity.

Such corporations need to change their perspectives before they find themselves peddling products of so little value that they can no longer retain a customer much less create one. |

IBM's sales productivity is in a two-decade decline

|

Corporate America once again needs a restart—or in IBM’s case a kick start—because although the value of Peter F. Drucker’s knowledge worker is still relevant, the best-of-the-best are evolving to provide higher value. They are reaching out through new communication vehicles, such as social media, to expand their value through engagements with other like-minded individuals. American corporations need to not only encourage these networks that fire the passion, enthusiasm and engagement of the individual, but also develop processes and advance belief systems that encourage such teams to find common cause in the service of their stakeholders: customers, fellow-employees, shareholders and society.

The Responsibility of the Chief Executive

Chief executives need to master the art of a Patterson Restart. They need to seek new perspectives by figuratively moving their desks out onto their knowledge-industry production floors. Tom Peters called it MBWA—management by wandering around. It is the responsibility of the corner office to release the potential of their knowledge-industry workplaces. This will require leaders that can master the art of the restart: increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of their employees by being constantly aware of their needs in an ever-evolving workplace.

The art of the restart is about actively pursuing these perspectives and taking action.

We need more crazy chief executives.

The art of the restart is about actively pursuing these perspectives and taking action.

We need more crazy chief executives.