Review of "Alexander Graham Bell: The Man Who Contracted Space"

|

|

Date Published: March 29, 2020

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

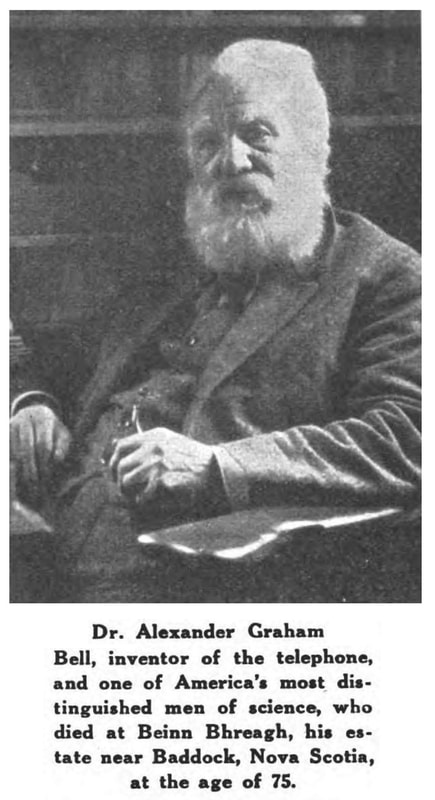

Genius as he was, Graham Bell was wholly incapable of applying any one of his own conceptions to a practical end. To Bell, the search for knowledge was the only really absorbing thing in the world. Goals were never as important to him as his progress toward them. His wife, always his closest companion, lamented that “he never wanted to finish anything,” and that “he would be tinkering with the telephone yet if I hadn’t taken it away from him.”

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

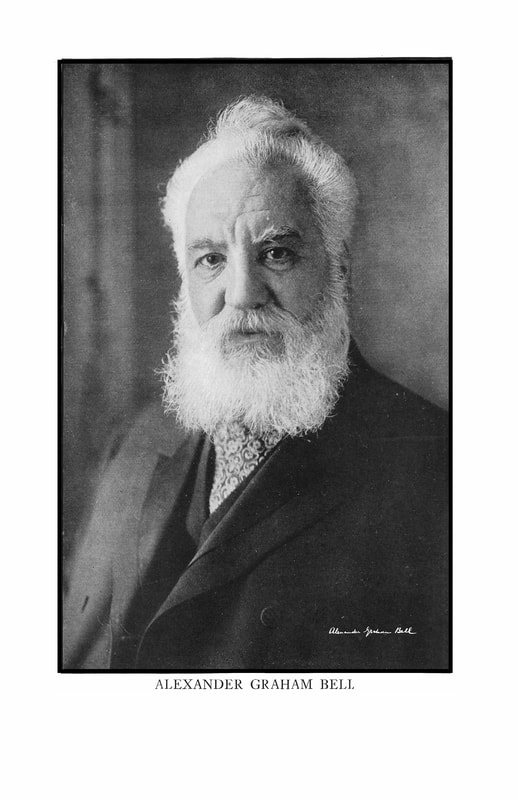

A Review of "Alexander Graham Bell" by Catherine Mackenzie

- Reviews of the Memoir When Published in 1928

- Insights Gained from this Work

- Final Thoughts of this Author

- Comparing Three Great American Inventors

A Review of "Alexander Graham Bell: The Man Who Contracted Space"

Reviews of the Memoir When Published in 1928

“This is the first authoritative life of one of America’s greatest inventors, written by one who was closely associated with him during the last eight years of his life.

"Naturally, in the course of the long hours thus spent, Miss Mackenzie heard from his own lips many reminiscences of his long life and labors and multiple interests. Many of these she has used in writing his biography, in addition to the store of facts and incidents gleaned from the many volumes of Mr. Bell’s own typewritten record, which Miss Mackenzie had edited for him.

There is every reason to believe that here is as authentic a biography as it is humanly possible to produce.”

"Naturally, in the course of the long hours thus spent, Miss Mackenzie heard from his own lips many reminiscences of his long life and labors and multiple interests. Many of these she has used in writing his biography, in addition to the store of facts and incidents gleaned from the many volumes of Mr. Bell’s own typewritten record, which Miss Mackenzie had edited for him.

There is every reason to believe that here is as authentic a biography as it is humanly possible to produce.”

The Jacksonville Daily Journal, May 18, 1928

|

It seems that every reviewer was impressed with the fact that Catherine Mackenzie was with Mr. Bell for the last years of his life and had open access to his innumerable notes. Many called it the first “authoritative work” on the life of one of America’s greatest inventors. Graham Bell was fastidious in his writing and retention of accurate notes for posterity. Because of this long, open relationship between author and subject, one reviewer commented that this biography was, for all intent and purposes, an autobiography. Miss Mackenzie was with her subject for the last eight years of his life and was closely associated with him “in every phase of his many activities.” Six years after his death she published this work. She dedicated more than a decade of her life studying the inventor’s life and habits.

All reviewers were captivated by the story of Mr. Bell’s attendance at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, where, were it not for Dom Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil, who noticed Alexander Graham Bell and his new invention in an obscure corner of an education exhibit, history would have been written quite differently. Because of a chance glance, and a moment of recognition between an emperor and a teacher of elocution to the deaf, the telephone was pulled from more than twenty-acres of exhibits and highlighted as “one of the sensations of the Centennial.” To the Brazilian Emperor and the centennial’s judges, Alexander Graham Bell recited over his new invention, “To be, or not to be, that is the question …” This day was a “to be” day for this young man with a new idea. |

Forbes, April 15, 1922

|

Some reviewers relished the detailed analysis that Miss Mackenzie gave to the long, tedious and bitter fights that Mr. Bell suffered over his patent rights. She proved what she declared openly in the book: “Probably no inventor ever lived who could and did show a clearer title to his invention.” There were ultimately close to 600 lawsuits, and in every instance the courts sustained Graham Bell as the original inventor. Five of these suits went to the Supreme Court and all five decisions ended in Bell’s favor. Unfortunately, the constant attention drawn to such a large number of lawsuits damaged Bell’s public reputation.

His true character was rarely captured in print. Of this, Miss Mackenzie wrote:

"The search for truth was the one really important thing in Bell’s life. It is the irony of his story that the malicious charges of fraud, widespread against him during the long and determined effort to wrest the telephone from him, were in complete contradiction to everything essential in his character.

"Honest, courageous, scornful of double-dealing, the incontrovertible evidence of his prior invention, and his repeated vindication by the courts as 'an honest man with clean hands,' were for years unavailing to quell these charges.

"They have persisted, ghosts of their once lusty selves."

His true character was rarely captured in print. Of this, Miss Mackenzie wrote:

"The search for truth was the one really important thing in Bell’s life. It is the irony of his story that the malicious charges of fraud, widespread against him during the long and determined effort to wrest the telephone from him, were in complete contradiction to everything essential in his character.

"Honest, courageous, scornful of double-dealing, the incontrovertible evidence of his prior invention, and his repeated vindication by the courts as 'an honest man with clean hands,' were for years unavailing to quell these charges.

"They have persisted, ghosts of their once lusty selves."

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

It is easy to understand why Alexander Graham Bell, more than once, wanted to walk away from his invention and let others take it. Truth, in the face of greed, never endures easily. It takes brave men to wither the storms of maliciousness driven by avarice to profit off another individual’s hard work. This is clearly laid out in this biography of Alexander Graham Bell.

Insights Gained from this Work

- Sometimes a weakness can become your greatest strength

Sometimes the specialized, engineering mind may prevent an individual from seeing all the possible solutions. The creative inventor thinks outside the box for solutions to a problem. In the case of electronic speech, Alexander Graham Bell wasn’t looking outside the box so much as he was standing outside the box looking in—he knew next to nothing about electricity. The telephone had to be seen as an instrument of speech not a construct of electricity.

"Bell knew next to nothing about electricity. He was a specialist in speech, and his idea had grown out of his expert knowledge of the voice, its physical mechanism, and of sound. “If Bell had known anything about electricity,” Moses G. Farmer [a fellow inventor] said a year later, “he would never have invented the telephone.” …

"Bell, alone of the many experimenters in the field, had hit upon this fundamental principle of electric speech in his ignorance of electricity and in his knowledge of sound."

- Your greatest strength can be your greatest weakness

This great inventor always tested out even the most basic of scientific premises. Although this gave him a wide and deep understanding of basic principles, it also slowed down his work and limited his possible achievements.

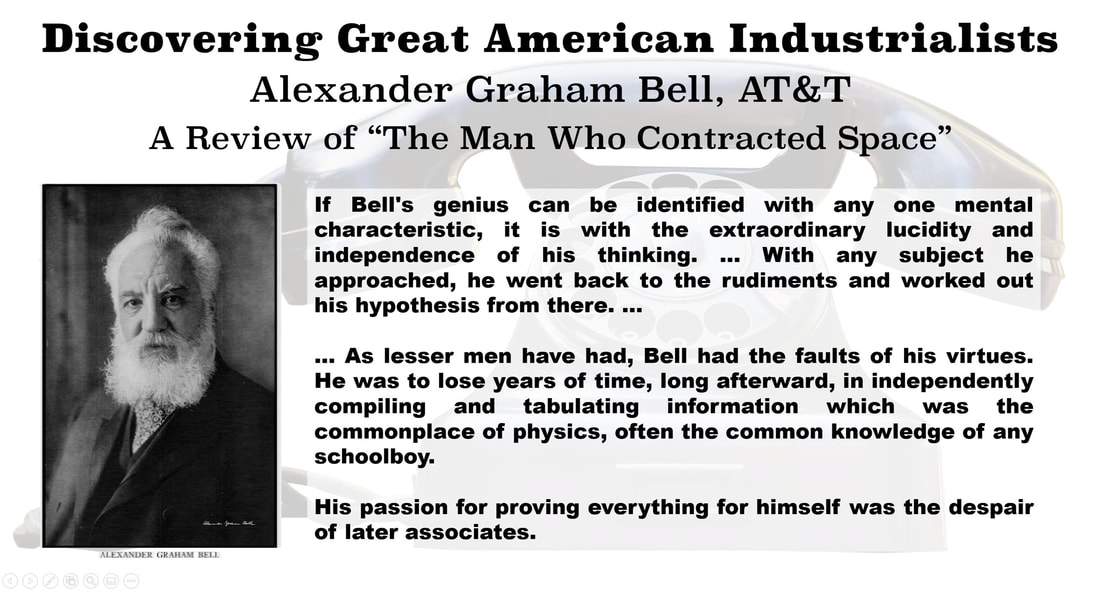

"If Bell’s genius can be identified with any one mental characteristic, it is with the extraordinary lucidity and independence of his thinking. … With any subject he approached, he went back to the rudiments and worked out his hypothesis from there. Once he had the facts or first principles, he formed his own conclusion. And when he had formed it, he stuck to it with the tenacity of ten men.

"As lesser men have had, Bell had the faults of his virtues. He was to lose years of time, long afterward, in independently compiling and tabulating information, which was the commonplace of physics, often the common knowledge of any schoolboy.

"His passion for proving everything for himself was the despair of later associates."

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

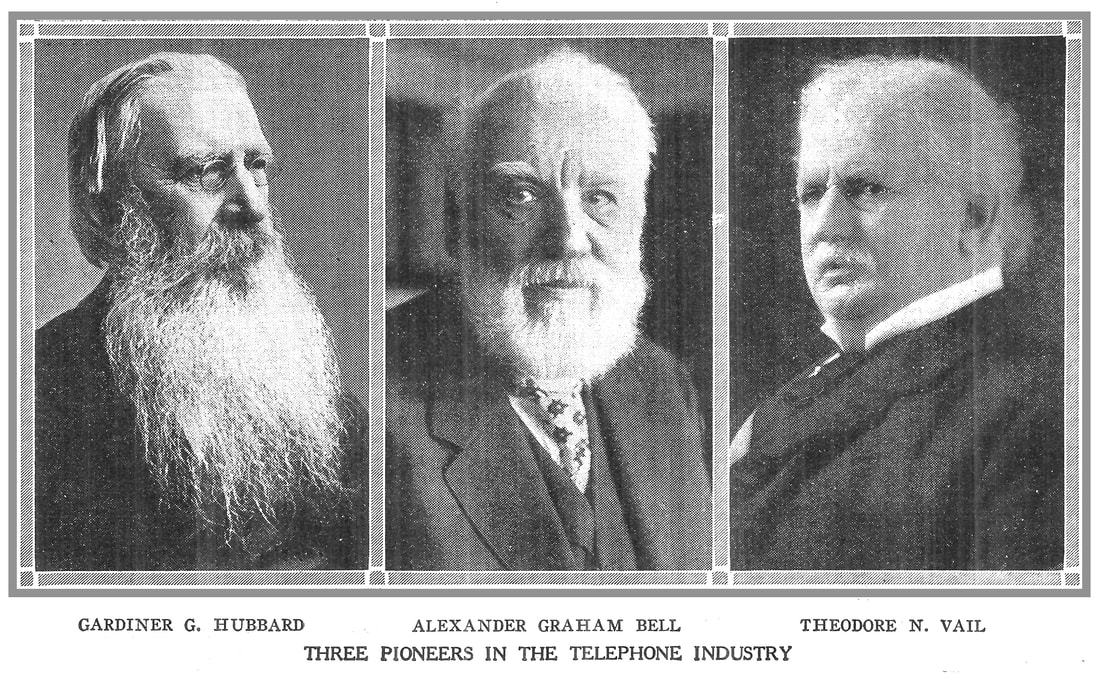

- A capitalist's investment built a whole industry and he was due a return

As highlighted above, Graham Bell was not an industrialist. He wasn’t a capitalist either. When he needed funding to start and grow the business, those funds came from Thomas Sanders, the merchant father of one of Alexander Graham Bell’s deaf students. It was an example of how a merchant – turned capitalist – funded and kept a business on its feet. He was due an appropriate return on his assumed risk that no one else, at the time, could or would take.

|

"Thomas Sanders was keeping the Bell telephone on its financial feet in the United States. He was the only one of the associates who had any money at that time, and although he was not a man of great means he had a substantial business, and that priceless ingredient of business—credit. … He now threw the whole weight of his personal and financial influence back of the telephone.

"As months passed and increasingly large bills were run up for manufacturing and other expenses, Sanders met them out of his personal funds until that source was exhausted, and then he borrowed on his own note. … "Sanders eventually advanced upwards of a hundred thousand dollars, imperiling his business and facing ruin, before he received a penny from the telephone in return." Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

|

- Laugh out loud moment

Miss Mackenzie writing of the times when the Bell family sailed for Canada from England related an incident in London between Bishop Wilberforce and a Professor Huxley on the topic of evolution.

"Bishop Wilberforce asked of Professor Huxley whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey. Huxley followed with a famous retort, “I am not ashamed to have a monkey for an ancestor, but I would be ashamed to be connected with a man who uses great gifts to obscure the truth.”

- Sometimes just being a fighter isn’t enough – friends provide support

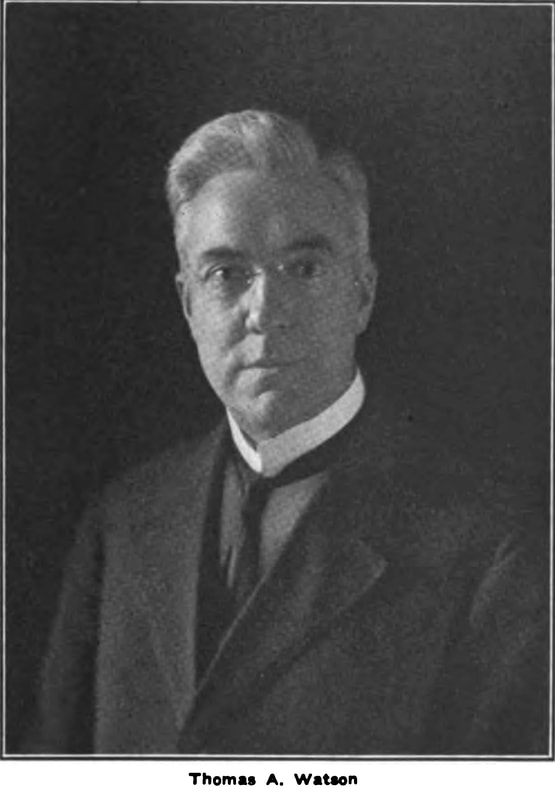

History does little to remember Watson as more than a gopher on the other end of the first telephone call who heard, “Mr. Watson – Come here – I want to see you.” This biography brings home that this man should be remembered as more. If not for Mr. Watson, Bell would be remembered as an obscure inventive tinkerer rather than the founder of a new industry that challenged and eventually displaced the telegraph.

Bell was an inventive genius, but that would never have been enough for him to have secured a place in posterity. Those around him supported and raised him up—especially Watson. Miss Mackenzie captures a time when Bell was in utter despair over the court battles:

|

"Bell was a fighter, but he fought fair, and the chicanery he had encountered in his efforts to establish the telephone … perplexed and then angered him. The whole sorry business was nauseous to a man of Bell’s rigid honesty. … He would go back to his profession, to a field he knew. … His expenses had been heavy. He had a wife and child on his hands, he was harassed with debts, and he was out of funds. …

"Watson was dispatched. …" Watson [found Bell], “even more dissatisfied with the telephone than his letters had indicated. He told me that he wasn’t going to have anything more to do with it but was going to take up teaching again as soon as he could get a position. Watson succeeded in convincing Bell that the telephone had an assured future in the United States." And it surely did! |

Electrical Review, Jan 11, 1913

|

- Even the greats are still human

All human beings make mistakes and have weaknesses that prevent them from achieving more. Graham Bell was no exception. His coping mechanism in facing obstacles was to go to bed feigning illness.

"This was genuine illness, yet, in the circumstances, it was one of Bell’s most characteristic gestures. Illness was always his defense. It defended him alike from the pleas of duty and from uncongenial social demands.

"When he was angry or bored, he went to bed. It saved argument."

Shouldn’t it be accepted that all human beings have weaknesses?

- The final joke on them all

After all the suits, court battles and trips to the Supreme Court, it seems that Mr. Bell had a laugh at the expense of those who would attempt to profit from the inventive work of others. Graham Bell was not only responsible for sending voice over wires, but the first prototype of the photophone—the wireless transmission of voice by light. Bell sealed up all his records of the invention of the photophone and deposited them with the Smithsonian Institution for preservation.

An amusing story came of the incident.

"Somehow the news leaked out that Alexander Graham Bell had deposited a sealed package in the Smithsonian Institution, and the rumor grew that its contents concerned an invention for seeing by telegraph. Somewhere a news paragraph appeared to this effect and was widely copied. … Instantly furious inventors wrote to the papers on two sides of the Atlantic, each claiming the invention as his own, denouncing Bell as a fraud and his alleged discovery as a theft!

"Of course, he had not discovered any method of seeing by telegraph, and neither had they.

"Forty years and more were to elapse before any one did see by electricity."

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

Final Thoughts of this Author

|

Men Who Are Making America, 1919

|

As much as this work is about Alexander Graham Bell, it is also an excellent example of how no man is an island unto himself. Graham Bell needed his wife, his extended family, Thomas A. Watson (highlighted above) and others to achieve success. This is not to take anything away from Mr. Bell, for the question must always be asked, “Can any man truly standalone without encouragement and support from others?”

This is one of the best passages about the value that Watson consistently brought to the table. Bell was peculiarly helpless in doing anything with his hands. Yet Watson gave more than his services as a skilled mechanic to the invention of the telephone. He had an unusually quick intelligence, and his imagination, enthusiasm, and loyalty were assets as valuable to the temperamental Bell as were industry and skill. Watson’s serenity, sympathy, and zeal were added to Bell’s genius in an auspicious hour. Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

|

Throughout the book Bell’s dependence on others becomes obvious and is well explained. Yet, nothing should be taken away from him as the following passage documents how much he and his wife and children withstood prior to profiting from his invention.

Sharp reality began to wear through the brave stuff of his fancy: the reality of unpaid rent; of pitiful little personal loans that left stinging marks in pride untouched by frayed cuffs and shabby coats; the realization that to his world he was not at all the romantic figure of penniless genius of his mind’s eye, but only a ‘tiresome young man who neglected profitable inventions to pursue chimerical ideas.’

Sharp reality began to wear through the brave stuff of his fancy: the reality of unpaid rent; of pitiful little personal loans that left stinging marks in pride untouched by frayed cuffs and shabby coats; the realization that to his world he was not at all the romantic figure of penniless genius of his mind’s eye, but only a ‘tiresome young man who neglected profitable inventions to pursue chimerical ideas.’

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell

In this case his chimerical idea—the telephone—returned a rich reward to the man … his family … and his society which at times treated him with disdain. This book is a good read for those who need to understand that sometimes greatness only arrives after years of great adversity, and that greatness is rarely achieved without help.

Comparing Three Great American Inventors

Comparing three great inventors of the day, Carl W. Ackerman in his Biography of George Eastman wrote the following of Thomas Alva Edison, George Eastman and Alexander Graham Bell: [the order in which the men are mentioned has been reversed for a better flow with this review]:

Eastman, Edison, and Bell differed from each other in their business viewpoints.

Eastman, Edison, and Bell differed from each other in their business viewpoints.

- Eastman … was fascinated by the business possibilities of photography. We noted … his early letters to large-scale production at low costs. … He went to England before he started manufacturing … [going] after the European as well as the home market. Finally, his reference to extensive advertising shows that … he had established … fundamental business principles upon which he was to build his concern.

- Edison … was a wizard with little interest in those [early] days in the commercial possibilities of his inventions, one of which he put away on a shelf for several years, unconcerned with its market potentiality. What Edison lacked in business acumen, however, others supplied. In his tribute to Coffin [President of General Electric Corporation], the first business genius in the electrical world, Edison declared: “He was one of the greatest among the men who have so greatly contributed to the surprising increase in the wealth and prosperity of the United States.”

Carl W. Ackerman, George Eastman, 1930

|

American Review, October 1921

|

Eastman was first and foremost a businessman, then a manufacturer and then an inventor. Edison was first and foremost an inventor who, later in life, learned the value of patenting and building a business on those patents. Alexander Graham Bell, in comparison, was different. Catherine Mackenzie wrote this of the inventor only a few years before Mr. Ackerman wrote his observations of the three inventors above, possibly drawing on Catherine’s own earlier observation:

Genius as he was, Graham Bell was wholly incapable of applying any one of his own conceptions to a practical end. To Bell, the search for knowledge was the only really absorbing thing in the world. Goals were never as important to him as his progress toward them. His wife, always his closest companion, lamented that “he never wanted to finish anything,” and that “he would be tinkering with the telephone yet if I hadn’t taken it away from him.”

Genius as he was, Graham Bell was wholly incapable of applying any one of his own conceptions to a practical end. To Bell, the search for knowledge was the only really absorbing thing in the world. Goals were never as important to him as his progress toward them. His wife, always his closest companion, lamented that “he never wanted to finish anything,” and that “he would be tinkering with the telephone yet if I hadn’t taken it away from him.”

Catherine Mackenzie, Alexander Graham Bell