Lou Gerstner wrote, "People truly do what you inspect, not what you expect." … Lest we forget, these "inspection pages" exist because chief executives are "people" too.

Arvind Krishna: 2020-23 IBM Employment Security

- Arvind Krishna's 2020-23 IBM Employment Numbers

- Evaluating Arvind Krishna's 2020-23 IBM Employment Security

Too many authors, historians, and corporate executives do not understand the difference between "job" security and "employment" security. The 20th Century IBM absolutely never promised "job" security. An individual's "job" was only secure as long as they performed. Opportunities were always available to try a new job, but fail at a "new job" and a person would not necessarily be fired, just returned to their previous job where they had performed.

When executives failed, this job change was sometimes called a "lateral move." This, though, gave an individual a chance to recover: to once again perform at a job they were good at and, given some time, more maturity, and additional training, to try again or to try another job that was more suited to their skills. It is easy to understand the critical nature of addressing poor performance, especially at the executive level. Tom Watson Sr. and Jr. both practiced "lateral moves" with their executives to address poor performance.

As for employees, first-line managers were pushed to their limits to determine if a person in a particular job was failing because of desire or ability. If it was desire, management was expected to create an environment that was conducive to support or inspire employee self-motivation. If it was ability, management was expected to put training in place or consider moving the individual to an area where their abilities would be the best match for a job.

This was a heavy burden on first-line management, but it was part of the management "job." If a person couldn't do this particular job, they could expect to be removed from management and moved back to where they had once performed. Peter E. Greulich covers a time when he was given such an ultimatum by his Administration Manager in "A View from Beneath the Dancing Elephant."

If an employee had the desire and the ability to perform, and they performed in their job they were secure in their "employment." If a particular type of "job" ended, they could expect to be offered another job (yes, possibly in another part of the country) and retrained if necessary, but they were again expected to perform to the highest standards in the new job. If an employee did not desire to work at the company or lacked the ability to perform . . . most of the time they would leave of their own volition because few are truly happy in a job they don't desire to do and/or have the ability to perform at. There were always the few, though, that had to be fired. This too was part of the management "job."

These concepts were the foundation for building and maintaining a "tradition" of full employment. It is a common misperception that IBM had a "policy" of full employment. Procter and Gamble had such a "policy." IBM never did. But it was one of the company's strongest of traditions because it was based on the employees' trust that management would do everything possible before considering the "nuclear options" of layoffs—referred to in the 21st Century IBM as right-sizing, resource actions, or workforce rebalancing.

In the 21st Century, IBM is practicing employment "insecurity." It doesn't matter what job or how well a person performs in any particular job, layoffs, right-sizing, resource actions, or workforce rebalancing threatens an individual's employment security. An instance of how IBM's most profitable division with some of the highest-performing individuals in the corporation were impacted in the 21st Century by a resource action is available on this website: [Read: How an R.A. Day Kills Productivity].

Let's take a look at Arvind Krishna's performance in this area from 2020 to 2023, and place it within the context of the 21st Century IBM employment practices since 2011 and 1999.

When executives failed, this job change was sometimes called a "lateral move." This, though, gave an individual a chance to recover: to once again perform at a job they were good at and, given some time, more maturity, and additional training, to try again or to try another job that was more suited to their skills. It is easy to understand the critical nature of addressing poor performance, especially at the executive level. Tom Watson Sr. and Jr. both practiced "lateral moves" with their executives to address poor performance.

As for employees, first-line managers were pushed to their limits to determine if a person in a particular job was failing because of desire or ability. If it was desire, management was expected to create an environment that was conducive to support or inspire employee self-motivation. If it was ability, management was expected to put training in place or consider moving the individual to an area where their abilities would be the best match for a job.

This was a heavy burden on first-line management, but it was part of the management "job." If a person couldn't do this particular job, they could expect to be removed from management and moved back to where they had once performed. Peter E. Greulich covers a time when he was given such an ultimatum by his Administration Manager in "A View from Beneath the Dancing Elephant."

If an employee had the desire and the ability to perform, and they performed in their job they were secure in their "employment." If a particular type of "job" ended, they could expect to be offered another job (yes, possibly in another part of the country) and retrained if necessary, but they were again expected to perform to the highest standards in the new job. If an employee did not desire to work at the company or lacked the ability to perform . . . most of the time they would leave of their own volition because few are truly happy in a job they don't desire to do and/or have the ability to perform at. There were always the few, though, that had to be fired. This too was part of the management "job."

These concepts were the foundation for building and maintaining a "tradition" of full employment. It is a common misperception that IBM had a "policy" of full employment. Procter and Gamble had such a "policy." IBM never did. But it was one of the company's strongest of traditions because it was based on the employees' trust that management would do everything possible before considering the "nuclear options" of layoffs—referred to in the 21st Century IBM as right-sizing, resource actions, or workforce rebalancing.

In the 21st Century, IBM is practicing employment "insecurity." It doesn't matter what job or how well a person performs in any particular job, layoffs, right-sizing, resource actions, or workforce rebalancing threatens an individual's employment security. An instance of how IBM's most profitable division with some of the highest-performing individuals in the corporation were impacted in the 21st Century by a resource action is available on this website: [Read: How an R.A. Day Kills Productivity].

Let's take a look at Arvind Krishna's performance in this area from 2020 to 2023, and place it within the context of the 21st Century IBM employment practices since 2011 and 1999.

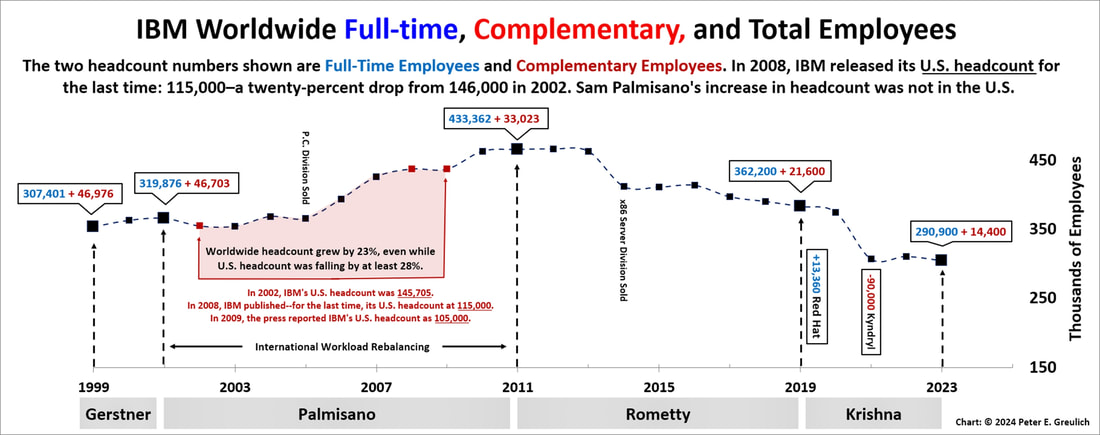

Arvind Krishna's IBM Employment Numbers

- Krishna 2019–23 Employment

- Full-time employees: Down 19.7% from 362,200 in 2019 to 290.900 in 2023

- Full-time complementary employees: Down 33.3% from 21,600 in 2019 to 14,400 in 2023 *

- Total worldwide full-time employee headcount: Down 20.5% from 383,800 in 2019 to 305,300 in 2023

- Krishna & Rometty 2011–23 Employment

- Full-time employees: Down 32.9% from 433,362 in 2011 to 290,900 in 2023

- Full-time complementary employees: Down 56.4% from 33,023 in 2011 to 14,400 in 2023 *

- Total worldwide full-time employee headcount: Down 34.5% from 466,385 in 2011 to 305,300 in 2023

- Krishna, Rometty, Palmisano & Gerstner 1999–2023 Employment: Up 5.9%

- Full-time employees: Down 5.4% from 307,401 in 1999 to 290,900 in 2023

- Full-time complementary employees: Down 69.3% from 46,976 in 1999 to 14,400 in 2023 *

- Total worldwide full-time employee headcount: Down 13.8% from 354,377 in 1999 to 305,300 in 2023

It is important to note that these are "worldwide" headcount numbers as IBM does not offer any geography specific headcount numbers like most other corporations around the world. This means for example that during Palmisano's tenure although employment numbers increased he was using "worldwide" resource balancing to ensure he made his yearly earnings-per-share numbers. So, there were significant, heart-wrenching reductions in the United States and Europe while work was transferred to lower-wage, but also lower productivity geographies. It was during this transition that IBM stopped publishing its employment numbers. No one today knows just how many IBM employees are left in the United States of America.

IBM last released its geographic and United States headcount numbers in its 2007 and 2008 Annual Reports.

Samuel J. Palmisano was less than transparent on his methodology of increasing earnings-per-share with U.S. and Europe workforce reductions. Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty and Arvind Krishna have continued to be opaque in this matter through the latest annual reports. So, it is impossible to provide accurate information about how these reductions may have impacted the United States, Europe, or any other geography.

How many employees still remain in the United States or Europe is a closely guarded secret held somewhere in IBM's Human Resources Department.

Reach out to me if you have the specifics: [link to contact information]

IBM last released its geographic and United States headcount numbers in its 2007 and 2008 Annual Reports.

- In IBM's 2007 Annual Report it provided the following information for the last time on employment in India: "The company has been adding resources aggressively in emerging markets . . . India experienced the largest growth, up 22,200 to approximately 74,000 employees at year end."

- In IBM's 2008 Annual Report it provided the following information for the last time on U.S. employment: "The U.S. remained the largest country, with 115,000 employees, while resources increased in Asia Pacific and Latin America and were essentially flat in Europe. The company continues to add resources aggressively in emerging markets, particularly in the BRIC countries-Brazil, Russia, India and China-where employment totals approximately 113,000."

Samuel J. Palmisano was less than transparent on his methodology of increasing earnings-per-share with U.S. and Europe workforce reductions. Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty and Arvind Krishna have continued to be opaque in this matter through the latest annual reports. So, it is impossible to provide accurate information about how these reductions may have impacted the United States, Europe, or any other geography.

How many employees still remain in the United States or Europe is a closely guarded secret held somewhere in IBM's Human Resources Department.

Reach out to me if you have the specifics: [link to contact information]

Being of service or caring about stakeholders other than customers—especially when it concerns employees, is sometimes called paternalism. When Watson Jr. talked about employment security, he did not view it as paternalistic but instead as a means of increasing employee loyalty, goodwill, and diligence on the job. These character traits in an employee improved an employee's productivity. It was just a good business practice.

Watson Sr. summarized best this father-and-son view of paternalism and employment security when he told his banking peers, “In attempting to counsel or advise those whom we employ, we must not adopt a paternal attitude. … When independent thought and action should be the order of the day, employees resent an attitude of paternalism. It is a well-known fact, however, that an employee’s efficiency suffers if his mind is ill at ease, and that worry over financial troubles is one of the most powerful sources for the destruction of mental peace.”

Employee efficiency suffers when employees constantly worry about their employment security.

Watson Sr. summarized best this father-and-son view of paternalism and employment security when he told his banking peers, “In attempting to counsel or advise those whom we employ, we must not adopt a paternal attitude. … When independent thought and action should be the order of the day, employees resent an attitude of paternalism. It is a well-known fact, however, that an employee’s efficiency suffers if his mind is ill at ease, and that worry over financial troubles is one of the most powerful sources for the destruction of mental peace.”

Employee efficiency suffers when employees constantly worry about their employment security.

* A complementary employee (with an "e" not an "i") came into existence during the IBM Crisis of 1992-93. It is defined in IBM's 2021 Annual Report as: "The complementary workforce is an approximation of equivalent full-time employees hired under temporary, part-time and limited-term employment arrangements to meet specific business needs in a flexible and cost-effective manner."

Evaluating Arvind Krishna's First-Year Employment Security

- How has Arvind Krishna performed in protecting or improving IBM's brand?

It seems that JUST Capital's positioning of IBM in its overall rankings since Arvind took over the corner office captures and documents the deteriorating perception of the IBM brand in the marketplace. IBM's brand has dropped in every JUST Capital survey over the last four years: falling from 11th to 60th place in the rankings:

- 2020 Results: 11th Place Overall - Arvind Krishna

- 2021 Results: 19th Place Overall - Arvind Krishna

- 2022 Results: 48th Place Overall - Arvind Krishna

- 2023 Results: 60th Place Overall - Arvind Krishna

The reason we don't use "Forbes' Best Employers" Yearly Listing is here: [Challenging Forbes Best Employers' List].

- How has Arvind Krishna performed in the area of employment security?

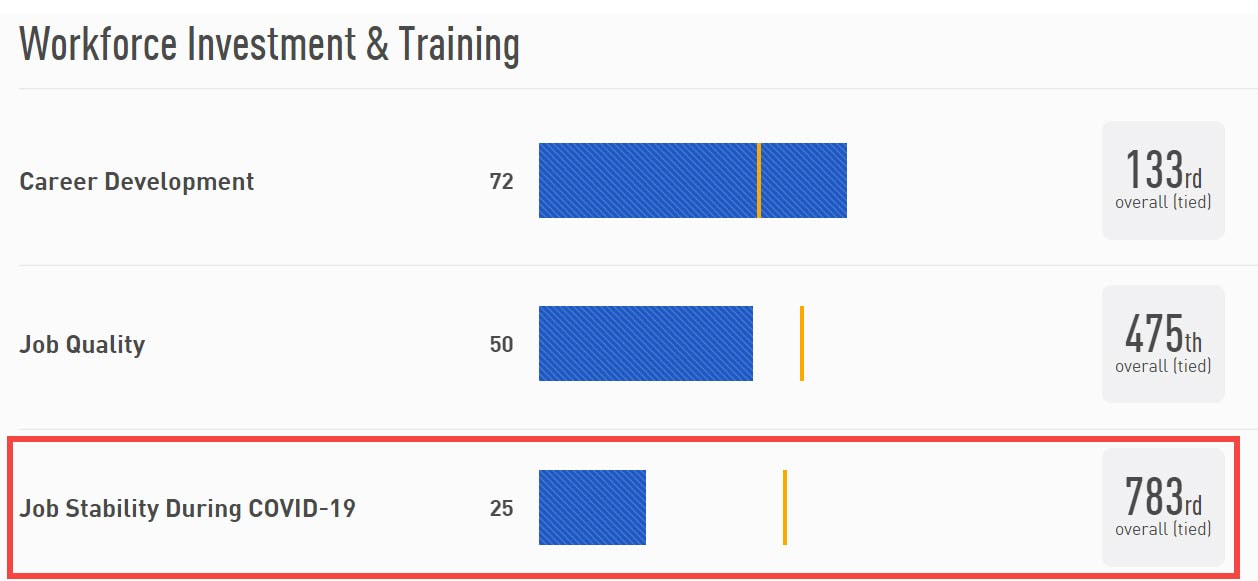

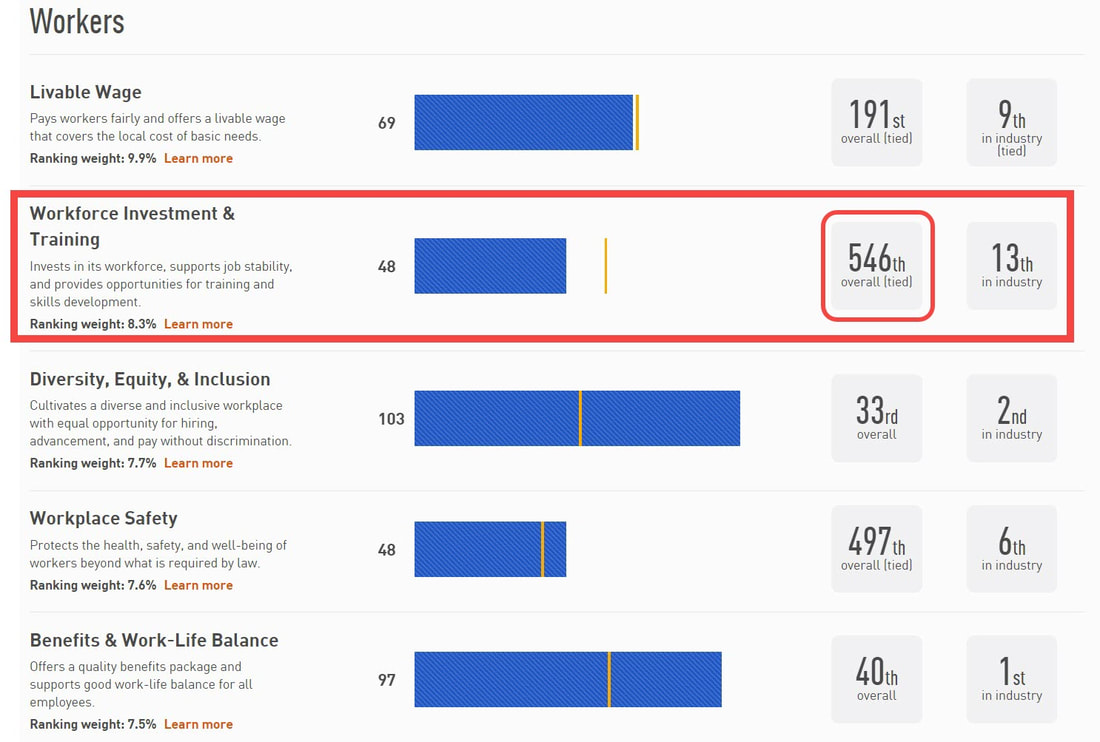

Information in the following charts is from JUST Capital's 2022 Overall Rankings information, unless otherwise noted. The latest information is not available to this detailed level, but as a reader may assume the details must have only gotten worse with IBM's dropping from 11th to 60th place in this timeframe.

|

As shown in the chart, JUST Capital gathered information in 2021 about IBM's "Workforce Investment and Training." The corporation placed 783rd for "Job Stability," 475th for "Job Quality," and 133rd for "Career Development."

In 2022, JUST Capital gathered information again. Unfortunately it modified its metrics and removed any measurement for "job stability."

This is what it wrote in its methodology report. |

In 2021, IBM was 783rd in employment security as described at the beginning of this article.

|

Invests in worker development: [changes from 2020 to 2021]

- 2020: Invests in its workforce, supports job stability, and provides opportunities for training and skills development.

- 2021: Invests in its workforce by providing training, education, and career development opportunities.

- Rationale: This concept is broader than simply training, as such the language should be more inclusive of education and career development. Removed “job stability” from language because JUST is not tracking layoffs.

I can't imagine too many U.S. employees that wouldn't support JUST Capital tracking layoffs and make it a major measurement as it did once in 2021. This only seems so . . . JUST.

|

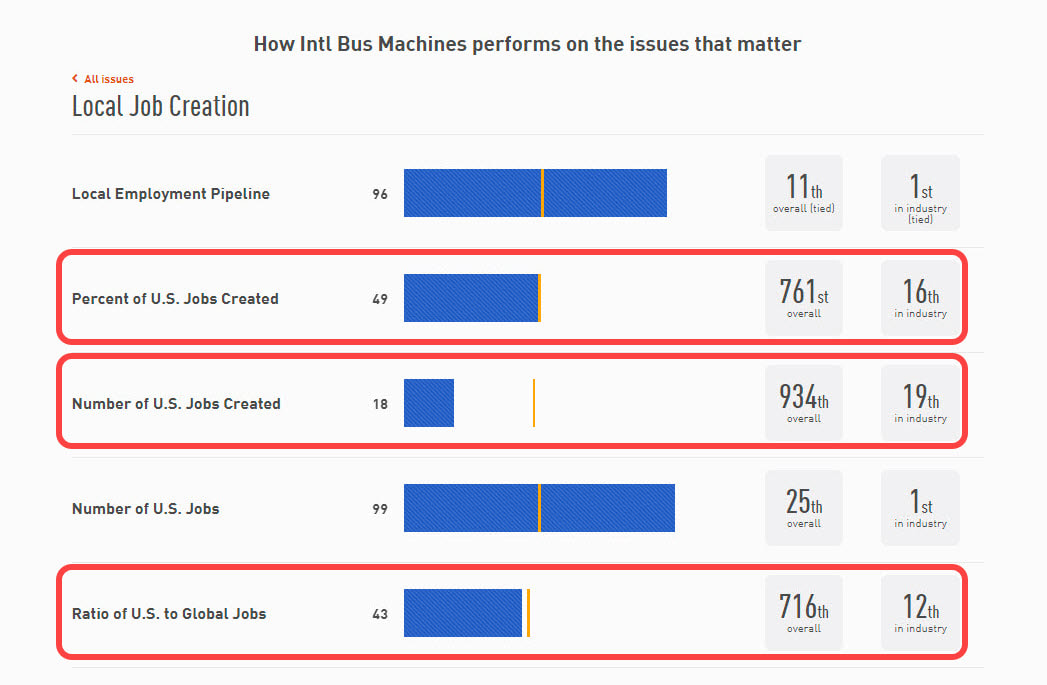

Arvind Krishna is as opaque as his predecessors. Unlike many of his counterparts, the corporation will not release its U.S. employment numbers. The reason may be that the information would be very embarrassing: In 2022, IBM ranked (1) 934th in "Number of U.S. Jobs Created," (2) 761st in "Percent of U.S. Jobs Created," and (3) 716th in "Ratio of U.S. to Global Jobs."

Employees that flippantly call IBM, "India Business Machines" are probably being more accurate than they can possibly guess. The 25th rank in "Number of U.S. Jobs" will probably drop quickly in the coming years. |

After taking the chief executive job in April, it only took Arvind Krishna a few months to announce employment cuts in the United States and by the end of 2020 he put in place a major shift of IBM's workforce out of Europe and Israel. Workforce reduction expenses that had averaged $487 million from 2005 to 2019 doubled to $956 million in 2020 and $752 million in 2021.

Amazingly the corporation believes that workforce reductions improve productivity. It published the following in its 2021 Annual Report: "In response to changing business needs, the company periodically takes workforce reduction actions to improve productivity." Short-term profit productivity maybe, but long-term sales and profit productivity has been flat or fallen throughout IBM's 21st Century [Read: Arvind Krishna's Sales and Profit Productivity].

The corner offices' failure to acknowledge this single fact explains its troubling inability to transform.

Amazingly the corporation believes that workforce reductions improve productivity. It published the following in its 2021 Annual Report: "In response to changing business needs, the company periodically takes workforce reduction actions to improve productivity." Short-term profit productivity maybe, but long-term sales and profit productivity has been flat or fallen throughout IBM's 21st Century [Read: Arvind Krishna's Sales and Profit Productivity].

The corner offices' failure to acknowledge this single fact explains its troubling inability to transform.

|

The overall 2022 JUST Capital categories for "issues

that matter to workers." |

It is very unfortunate that JUST Capital is no longer focusing on employment security because employment isn't about a single individual but about the employee's family and their common economic security and futures.

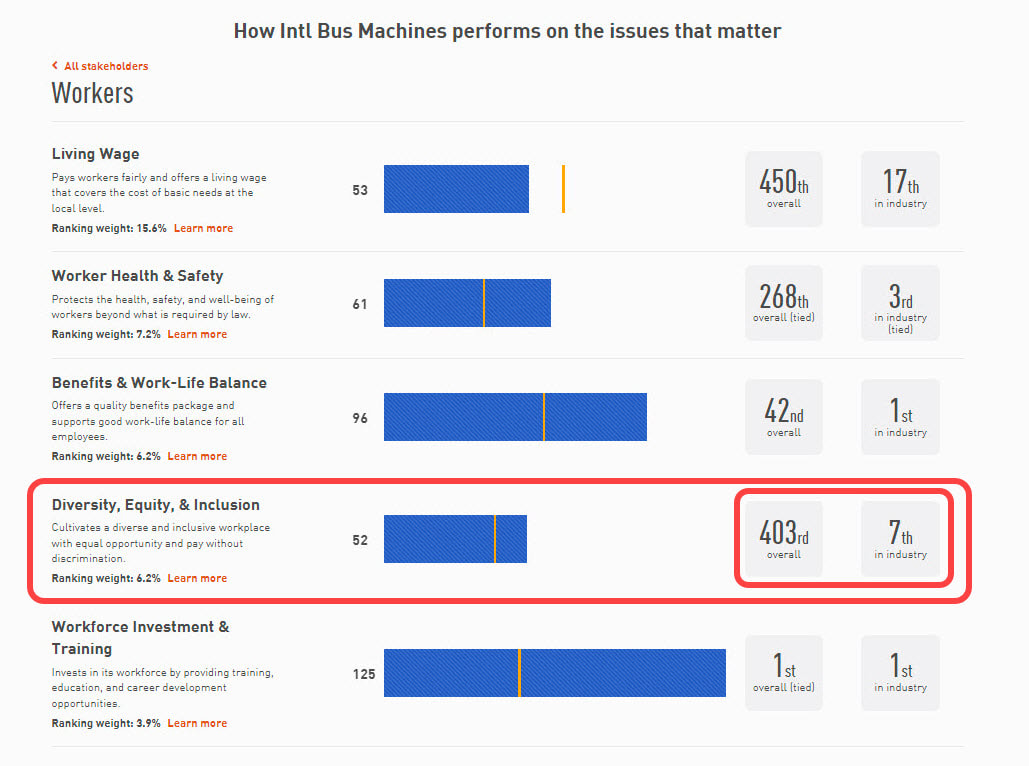

Fortunately, there are still enough areas measured for the reader to form their own conclusion. It does take some digging into the data, but they are there. IBM was ranked as follows:

|

* It is important to note that "job stability" was removed from the "Workforce Investment & Training" category in which IBM the year previously was ranked 546th. [See Footnote #1: Image provided]

Probably one of the most ironic statements in IBM's 2021 Annual report considering JUST Capital's ranking of IBM in the area of "Diversity, Equity & Inclusion" as 403rd across all industries and 7th in the Computer Services Industry with only twenty companies, is that they wrote the following after noting the corporation's progress on diversity and inclusion: "These efforts—and others—were recently recognized by JUST Capital, which named IBM the most just company in our industry."

Arvind Krishna and his staff, like many other researchers and analysts, just didn't look into the details. As we say in Texas, "The devil's in the details," and this award might have been better mentioned in an area in which IBM overachieved, not underachieved.

Who researches the details behind these corporate awards [Read: Challenging Forbes' 2020 World's Best Employer List]?

Arvind Krishna and his staff, like many other researchers and analysts, just didn't look into the details. As we say in Texas, "The devil's in the details," and this award might have been better mentioned in an area in which IBM overachieved, not underachieved.

Who researches the details behind these corporate awards [Read: Challenging Forbes' 2020 World's Best Employer List]?

|

[Footnote #1]: Kudos to JUST Capital for providing the detailed information behind its ratings and also providing the updates each year to its methodology changes.

It is concerning, though, that in one year IBM rose from 546th to 1st in "Workforce Investment & Training." This is difficult to explain, even with the change in wording to omit "job security" from the category. It leaves one wondering if JUST Capital examines its own detailed year-over-year data enough. Then again, no human system is perfect, is it? |

Issues that workers care about from JUST Capital in 2021.

|