Two Successful 20th Century Businesswomen

By Samuel Crowther in System, The Magazine of Business

|

|

Date Published: June 10, 2021

Date Modified: October 19, 2023 |

So many times, a son or daughter asks for advice on what it takes to succeed in business – or in life. The practices in this article are a hundred years old; yet, their value is timeless to those who desire to prove themselves to be the “best available person” for a job - or to the best wife or husband, mother or father, or sister or brother.

Consider the choice of discussions a parent has today when a son or daughter enters the business world but especially with a daughter: (1) use the role of victim to excuse away underachievement, or (2) discuss role models who achieved success through life’s hard-fought battles. This is the story of two women who succeeded in business in 1918.

It is a story to share with those who are more than priceless – those who call out “mom” or “dad” when they need advice.

Consider the choice of discussions a parent has today when a son or daughter enters the business world but especially with a daughter: (1) use the role of victim to excuse away underachievement, or (2) discuss role models who achieved success through life’s hard-fought battles. This is the story of two women who succeeded in business in 1918.

It is a story to share with those who are more than priceless – those who call out “mom” or “dad” when they need advice.

Two Successful Business Women

- Two Successful Business Women

- Have the “Right Stuff” and Sweat the "Small Stuff"

- Be Diligent and Learn from Mistakes

- Master the Art of Negotiation

- Delegate to Maintain Focus

- Expect Performance to Bring Promotions

[Paragraph headings have been added and minor edits performed by this author and are his sole responsibility.]

Two Successful Business Women

|

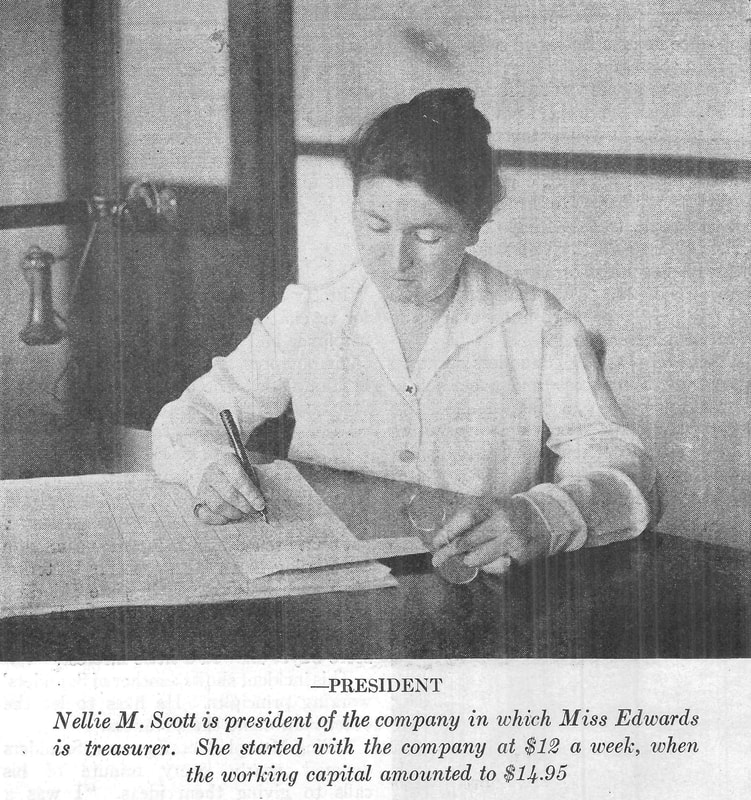

If you should get a check from the Bantam Ball Bearing Company you would find it signed "Nellie M. Scott, President – Ruth Edwards, Treasurer." Possibly you might conclude that the company, to save the time of the real executives, had, as is often the case, dummy officers, while the actual managers kept in the background and pulled the strings.

But if you happened into the busy little plant up in Connecticut, you would change your mind with celerity. For Miss Scott is a real president and Miss Edwards is a real treasurer. Both of the executives hold down their jobs for the sole reason that they were and are the best available people for them [emphasis added]; and both have made good in a striking way, as the surprising record of the company shows. Miss Scott helped found the company; Miss Edwards came in later, but both are alike in having started at the very bottom. |

Have the “Right Stuff” and Sweat the "Small Stuff"

W. S. Rogers, some years ago, casting about for a business that he could call his own, came upon an old barn-like structure at Bantam. It was equipped with a magnificent collection of unpaid bills and a small amount of worn machinery. But the bills were not his and the machinery could be; and then and there he decided to go on his own. The owners were glad to let him have the plant upon his promise to pay.

As a starter to an organization he wired to Detroit for Miss Scott to come on. He knew the young woman and her qualities, and he thought she had the nerve to stick. She had never worked, but she had taken a course at a business college. Such was her formal equipment. But Rogers knew she had the “stuff” – a level head, a keen eye, a capacity for managing people in a nice way, and a quick temper which acted as a high-speed motor, for it was under control.

Thereupon Miss Scott was inducted into the newly born company at a salary of $12 a week. Her duties were comprehensive; she was stenographer, bookkeeper, cost accountant, accountant, mail clerk, collector, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer. Mr. Rogers held the other offices and there is an open question as to who was shipping clerk—both Miss Scott and Rogers have plausible claims for the honor. There is no dispute, however, that in addition to her supposed offices Miss Scott did the sweeping and dusting.

As a starter to an organization he wired to Detroit for Miss Scott to come on. He knew the young woman and her qualities, and he thought she had the nerve to stick. She had never worked, but she had taken a course at a business college. Such was her formal equipment. But Rogers knew she had the “stuff” – a level head, a keen eye, a capacity for managing people in a nice way, and a quick temper which acted as a high-speed motor, for it was under control.

Thereupon Miss Scott was inducted into the newly born company at a salary of $12 a week. Her duties were comprehensive; she was stenographer, bookkeeper, cost accountant, accountant, mail clerk, collector, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer. Mr. Rogers held the other offices and there is an open question as to who was shipping clerk—both Miss Scott and Rogers have plausible claims for the honor. There is no dispute, however, that in addition to her supposed offices Miss Scott did the sweeping and dusting.

Be Diligent and Learn from Mistakes

Those were stirring times in the little company—it was then capitalized at only $25,000 and the cash capital on the first day the machinery started was $14.95. At the beginning of a month, Rogers and Miss Scott never knew where the end of the month would find them; they seldom had their payroll money more than a day in advance of pay day. But they always did pay their men and, if they could not find the money for material jobbers, they frankly laid their financial conditions before them and gained an extension.

The books were open to any person who had a right to look into them, and so accurate was Miss Scott's accounting that not a little of the credit for pulling the company through the early years is due to her; whenever bankers or creditors examined the books, they went away saying something to this effect: "Well, you know what you are doing all right. I'll take a chance with you."

Miss Scott knew nothing of mechanics or accounting when she started in; but she studied, and she looked; she seldom did anything wrong the second time, for when she did make a mistake, she wanted to know all about why and how she had made it. Her mistakes were not of judgment but due wholly to lack of knowledge of the subject matter.

The books were open to any person who had a right to look into them, and so accurate was Miss Scott's accounting that not a little of the credit for pulling the company through the early years is due to her; whenever bankers or creditors examined the books, they went away saying something to this effect: "Well, you know what you are doing all right. I'll take a chance with you."

Miss Scott knew nothing of mechanics or accounting when she started in; but she studied, and she looked; she seldom did anything wrong the second time, for when she did make a mistake, she wanted to know all about why and how she had made it. Her mistakes were not of judgment but due wholly to lack of knowledge of the subject matter.

Master the Art of Negotiation

As the business of the company grew, so did Miss Scott and it was not long before Rogers was giving to her the most important of the company's missions.

For instance, a big automobile company canceled a large contract by wire. Miss Scott took the next train to Michigan. She came back within a few days and, taking her desk, remarked to Rogers: "It is all right; they decided that they did not want to cancel." When Rogers next met the general manager of the automobile company the latter asked him, with a short laugh: “Why didn't you send someone out here that we could bluff?”

That is one of the strongest points about Miss Scott—you cannot bluff her. She always has the facts. She acts naturally and simply with the single thought in mind that if her facts are straight, then she is right, and she ought to have what she started out after. She knows what facts are and how to present them; when she finds that the other side is right, she is just as quick to concede the point.

The customers like her methods and the other executives, as well as the hands in the shop—all of whom are men—not only respect her but take her suggestions as readily as though she were a man. She now knows the proper mechanical method of the factory, she knows when a product is right and when it is not, she can put her finger very quickly on costs that are out of the way.

For instance, a big automobile company canceled a large contract by wire. Miss Scott took the next train to Michigan. She came back within a few days and, taking her desk, remarked to Rogers: "It is all right; they decided that they did not want to cancel." When Rogers next met the general manager of the automobile company the latter asked him, with a short laugh: “Why didn't you send someone out here that we could bluff?”

That is one of the strongest points about Miss Scott—you cannot bluff her. She always has the facts. She acts naturally and simply with the single thought in mind that if her facts are straight, then she is right, and she ought to have what she started out after. She knows what facts are and how to present them; when she finds that the other side is right, she is just as quick to concede the point.

The customers like her methods and the other executives, as well as the hands in the shop—all of whom are men—not only respect her but take her suggestions as readily as though she were a man. She now knows the proper mechanical method of the factory, she knows when a product is right and when it is not, she can put her finger very quickly on costs that are out of the way.

Delegate to Maintain Focus

|

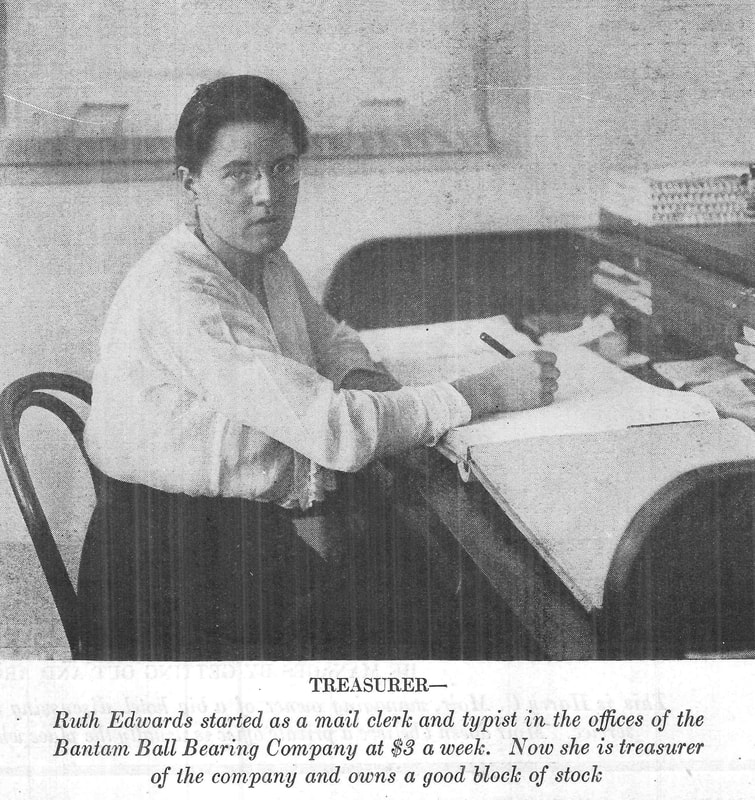

As the business grew Miss Scott had to delegate some of her duties. She engaged a young girl who lived in the town, Miss Ruth Edwards, for the task of opening mail and addressing envelops. Miss Edwards promised also to learn stenography if Miss Scott would teach her. For her services and her promises she received $3 a week. Miss Edwards quickly picked up stenography; then she started to help out Miss Scott with the bookkeeping and cost finding and within a few years she had ceased pounding the typewriter and was the official accountant for the company.

These two young women are almost opposites in disposition. Miss Scott is quick and volatile, while Miss Edwards gives the impression that nothing could disturb her. Between them they managed to keep the company on such an even keel that Rogers began less and less to look after any phase other than the engineering and designing. |

Expect Performance to Bring Promotions

He craftily shoved more and more work on the women and then watched. He satisfied himself that they were perfectly able to care for anything that might come up. Then he cast a bomb into their midst by presenting his resignation and asking for the resignation of all the officers. But he did not leave them long in the air. He addressed the directors somewhat in this fashion: "Miss Scott and Miss Edwards can run this business better than I can—maybe they do not know it. One of them ought to be president and the other treasurer; it will be enough for me to be chairman of the board of directors."

And thus, it came about that the company's checks are signed "Nellie M. Scott, President – Ruth Edwards, Treasurer." They are real executives drawing real and substantial salaries and each now owns a nice fat wad of stock in the company which she has done so much to build.

And thus, it came about that the company's checks are signed "Nellie M. Scott, President – Ruth Edwards, Treasurer." They are real executives drawing real and substantial salaries and each now owns a nice fat wad of stock in the company which she has done so much to build.