Explaining IBM's 20th Century Productivity Stall and 21st Century Productivity Fall

- The Precedent for the Golden Rule in American Business

- The Effect of IBM's Retirement Decisions

- Summary: The Golden Rule in Business

- Author's Comment: New Ideas, Fresh Thoughts from Old Minds

The Precedent for the Golden Rule in American Business History

|

"Money is important; but the practice of the golden rule in making money—as in every other aspect of human relations—is the most substantial asset of civilized man."

J. C. Penney, "Fifty Years with the Golden Rule "

"The simple rule to follow in all human relations is the golden rule. This rule applies to all human relations, great as well as small."

Thomas J. Watson Sr., President of IBM

"If you ask me with reference to business what is right in principle, I answer that the golden rule supplies all that a man of business needs. … What is right in business requires, in highly complicated situations, that the golden rule be applied by men of great understanding and knowledge, as well as conscience."

Owen D. Young, Chairman of the Board of GE

There were many other well-recognized industrialists who led long-lived corporations and applied the golden rule to their businesses—it is a lengthy list.

|

Ida M. Tarbell, best remembered as the muckraker who brought down Standard Oil Corporation, included an entire chapter on the golden rule in her autobiography "All in a Day’s Work." After dissecting John D. Rockefeller Sr.’s corporation, she began a new quest to discover if the golden rule had practical applications in business. She published the results of her four-year effort (1910-1914) in a book entitled "New Ideals in Business." In the concluding paragraph she writes of the businesses she visited:

"He [the businessman] is seeing a significance and a possibility in humanizing his relations that he formerly did not dream. He is developing the inspiring consciousness that it is possible for him to be not a mere manufacturer of things for personal profit, but as well a maker of men and women for society’s profit."

From IBM's productivity climb for more than eight decades, it seems the early 20th Century IBM leaders knew their stuff.

If Owen D. Young were to evaluate Gerstner, Palmisano, Rometty and Krishna, he would say that they have failed as "men [and women] of great understanding, knowledge and conscience."

"He [the businessman] is seeing a significance and a possibility in humanizing his relations that he formerly did not dream. He is developing the inspiring consciousness that it is possible for him to be not a mere manufacturer of things for personal profit, but as well a maker of men and women for society’s profit."

From IBM's productivity climb for more than eight decades, it seems the early 20th Century IBM leaders knew their stuff.

If Owen D. Young were to evaluate Gerstner, Palmisano, Rometty and Krishna, he would say that they have failed as "men [and women] of great understanding, knowledge and conscience."

The Effect of IBM's Human Relations' Decisions

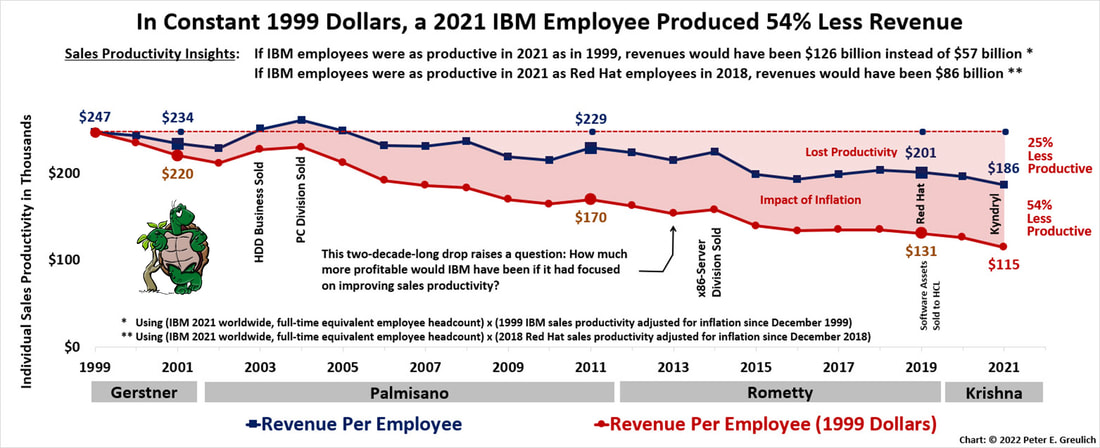

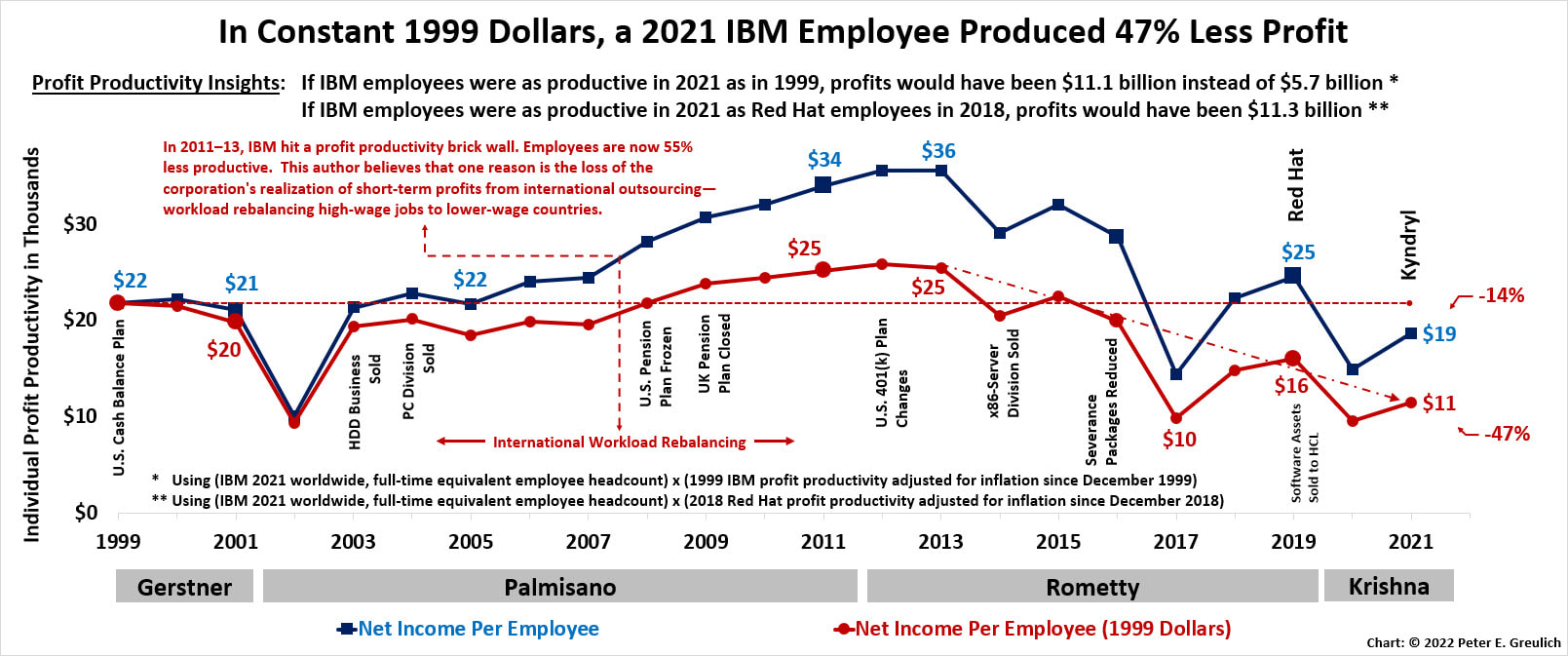

At the end of 2021, every single 21st Century IBM employee produced 25% less revenue and when adjusted for inflation, 54% less; every single 21st Century IBM employee produced 14% less profit and when adjusted for inflation, 47% less.

The revenue and profit productivity "tortoises" had overtaken the Gerstner-Palmisano-Rometty-Krishna profit hare. The "Productivity Insights" on each of the charts below get across the impact of these productivity losses on revenue and profits. It seems to be a lost message in the 21st Century but productivity matters!

Or as Tom Watson used to say, "Employee enthusiasm matters."

The revenue and profit productivity "tortoises" had overtaken the Gerstner-Palmisano-Rometty-Krishna profit hare. The "Productivity Insights" on each of the charts below get across the impact of these productivity losses on revenue and profits. It seems to be a lost message in the 21st Century but productivity matters!

Or as Tom Watson used to say, "Employee enthusiasm matters."

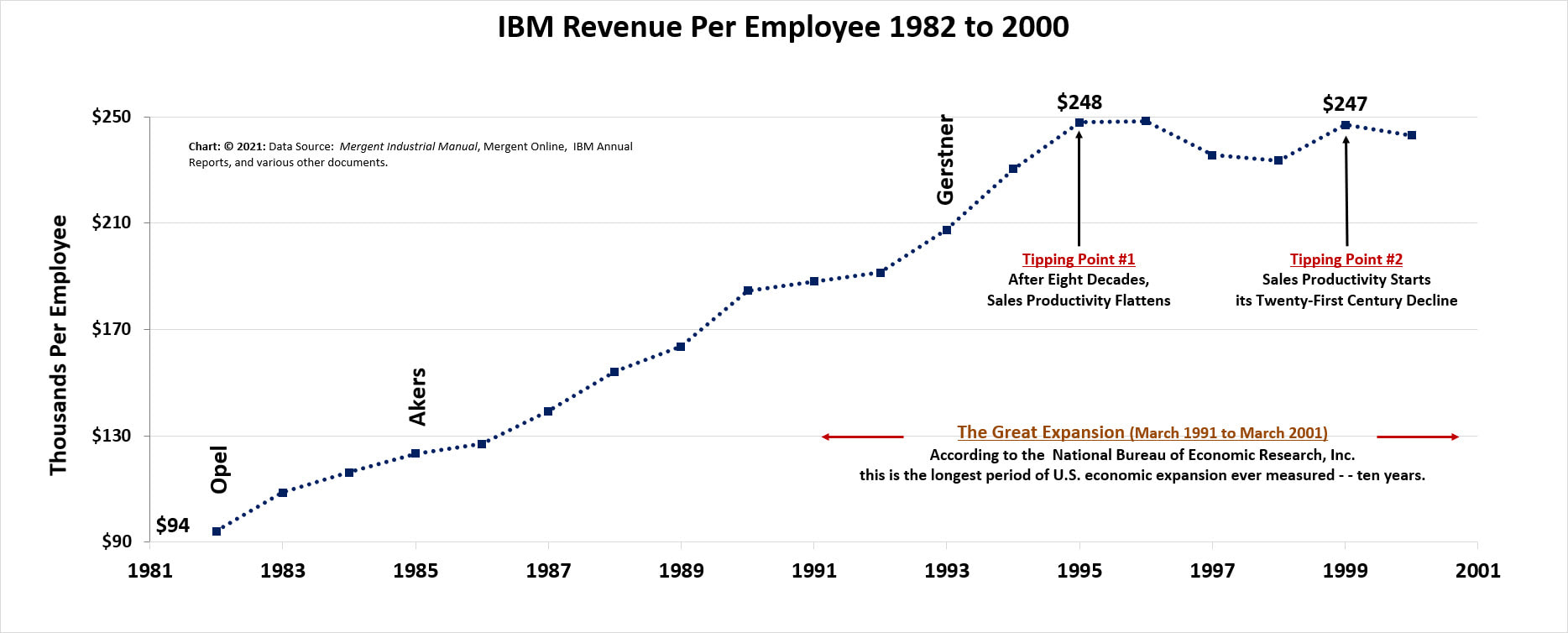

IBM's Revenue-Per-Employee Deterioration since 1999 Documents a Long-Term Fall in Employee Productivity and Enthusiasm

IBM's Profit-Per-Employee Deterioration since 1999 Documents a Long-Term Fall in Employee Productivity and Enthusiasm

IBM's macro-productivity problem is one indication of a long-term deterioration in the corporation’s employee enthusiasm, engagement and passion. For eight decades IBM’s sales productivity was in a continuous climb. In 1995 it flattened—a stall. In 1999, it started a two-decade decline—a fall.

This "stall and fall" in employee productivity started during "The Great Expansion." This was a ten-year period that the National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. (NBER) said was "the longest period of U.S. economic expansion ever measured." [Also See Footnote #2]

The tipping point for productivity was Louis V. Gerstner’s Pension Decision of 1999. Although by 1995 many employees had concluded that they could no longer trust the words of their corner office, this was the single change that sent the final, undeniable message to all U.S. employees. Let’s review the facts surrounding the 1999 decision that too many have forgotten, and which IBM’s chief executive failed to include in his self-evaluation Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?

In 1999, Louis V. Gerstner’s salary and bonus increased 8% to $14.8 million; he exercised stock options for an additional $87,000,000; real estate holdings were sold off and reengineering projects sent $9,500,000,000 to the bottom line; sales reached a record high of $87,548,000,000; sales productivity peaked at $247,048 per employee; the stock underwent two 2-for-1 stock splits; in 1995, the company restarted yearly dividend increases and over the next five years sent $3,700,000,000 to shareholders; stock buybacks which began in 1995 overwhelmed any other investment reaching a total of $32,000,000,000 over this five year period with net income an almost equally strong $29,740,000,000.

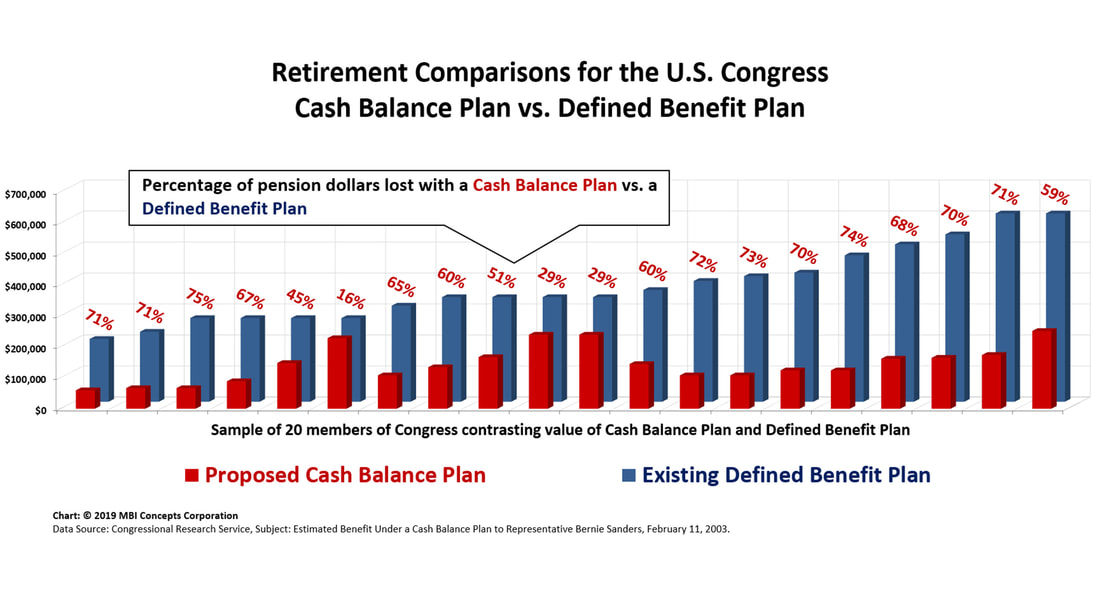

Everything pointed to the fact that IBM was back, and yet, Lou Gerstner drastically cut the retirement benefits of the very individuals who had worked by his side since 1993 to save the corporation. The size of these cuts is hard to comprehend but a congressional report requested by Bernie Sanders helps visualize the effects of these pension conversions on Lou’s coworkers.

If a similar conversion (Cash Balance Plan) had been made in congressional retirement benefits, the individual losses would have ranged from 16% to 75%, with seventy-five percent of the congressmen’s retirements in the study being reduced by sixty percent or more. This retirement change affected 140,000 U.S. IBM employees. At the time, this was half (45.5%) of the corporation’s full-time, worldwide population.

Sales productivity which flattened in 1995, now started to decline.

In 1999, Louis V. Gerstner’s salary and bonus increased 8% to $14.8 million; he exercised stock options for an additional $87,000,000; real estate holdings were sold off and reengineering projects sent $9,500,000,000 to the bottom line; sales reached a record high of $87,548,000,000; sales productivity peaked at $247,048 per employee; the stock underwent two 2-for-1 stock splits; in 1995, the company restarted yearly dividend increases and over the next five years sent $3,700,000,000 to shareholders; stock buybacks which began in 1995 overwhelmed any other investment reaching a total of $32,000,000,000 over this five year period with net income an almost equally strong $29,740,000,000.

Everything pointed to the fact that IBM was back, and yet, Lou Gerstner drastically cut the retirement benefits of the very individuals who had worked by his side since 1993 to save the corporation. The size of these cuts is hard to comprehend but a congressional report requested by Bernie Sanders helps visualize the effects of these pension conversions on Lou’s coworkers.

If a similar conversion (Cash Balance Plan) had been made in congressional retirement benefits, the individual losses would have ranged from 16% to 75%, with seventy-five percent of the congressmen’s retirements in the study being reduced by sixty percent or more. This retirement change affected 140,000 U.S. IBM employees. At the time, this was half (45.5%) of the corporation’s full-time, worldwide population.

Sales productivity which flattened in 1995, now started to decline.

In 2008, Samuel J. Palmisano froze this plan to drive additional profits to the bottom line, increase already record profits, and reach a summit of stock buybacks: The combined years of 2007 and 2008 were the largest back-to-back stock repurchases in the corporation’s history to that time: $29,346,000,000.

In 2009, Sam then closed the U. K. pension plan (pension “scheme” in their parlance), and over the next two years set the corporation’s all-time, back-to-back, historical stock buyback record: $30,453,000,000. Meanwhile, in 1999 inflation adjusted dollars, sales productivity kept declining.

In 2012, Virginia M. Rometty went after the replacement for this defined-benefit plan that is the lifeblood of the next generation’s retirements. To drive more profits to the bottom line, she inserted fine print into the existing 401(k) retirement agreements: (1) the company only makes one lump-sum, matching payment to employee accounts on December 31 so that the corporate matching dollars are no longer dollar-cost averaged into the market throughout the entire year which increases investment risk, and (2) anyone who leaves prior to December 15—for any reason other than a formal retirement—will not receive this lump sum company match for that year. As a result, she came close to matching Palmisano’s two-year, share buyback records: $27,672,000,000. And sales productivity, in 1999 inflation adjusted dollars, continued its fall.

Immediately after the 401(k) modification, stock repurchases fell by seventy-five percent and remained comparatively anorexic as the once fatted calves—old and new worldwide retirement plans—have little left to contribute to these chief executive officers’ paper repurchasing scheme [Although IBM still has money approved to make further stock buybacks, Arvind Krishna has so far not used these "preapproved" funds].

And with productivity in a constant fall, there was no way to drive higher profits.

Ultimately, productivity improvements are the root of profits.

In 2009, Sam then closed the U. K. pension plan (pension “scheme” in their parlance), and over the next two years set the corporation’s all-time, back-to-back, historical stock buyback record: $30,453,000,000. Meanwhile, in 1999 inflation adjusted dollars, sales productivity kept declining.

In 2012, Virginia M. Rometty went after the replacement for this defined-benefit plan that is the lifeblood of the next generation’s retirements. To drive more profits to the bottom line, she inserted fine print into the existing 401(k) retirement agreements: (1) the company only makes one lump-sum, matching payment to employee accounts on December 31 so that the corporate matching dollars are no longer dollar-cost averaged into the market throughout the entire year which increases investment risk, and (2) anyone who leaves prior to December 15—for any reason other than a formal retirement—will not receive this lump sum company match for that year. As a result, she came close to matching Palmisano’s two-year, share buyback records: $27,672,000,000. And sales productivity, in 1999 inflation adjusted dollars, continued its fall.

Immediately after the 401(k) modification, stock repurchases fell by seventy-five percent and remained comparatively anorexic as the once fatted calves—old and new worldwide retirement plans—have little left to contribute to these chief executive officers’ paper repurchasing scheme [Although IBM still has money approved to make further stock buybacks, Arvind Krishna has so far not used these "preapproved" funds].

And with productivity in a constant fall, there was no way to drive higher profits.

Ultimately, productivity improvements are the root of profits.

Summary: The Golden Rule in Business

|

America’s greatest, twentieth-century business leaders were hands-on artisans whose results speak for themselves. They took pride in building corporations held to the highest of ethical standards. They interweaved the threads of fairness, equality and justice into the very fabric of their corporations. Their golden-rule driven, human relation looms took thousands of high-powered, individualistic natures and produced cooperative work families.

Employees trusted their corner offices, and customers, shareholders and societies trusted the corporation’s employees. This is the essence of properly decentralized organizations.

|

Great CEO's weave the basics of the Golden Rule into their corporations.

|

Obviously, the actions of Lou, Sam, Ginni and Arvind have not been cut from the same cloth.

Author’s Comment: New Ideas, Fresh Thoughts from Old Minds

Surviving IBM’s Financial Crisis of 1992-93 and experiencing the Cultural Crisis of 1995-99 were two life-experiences that, if evaluated properly, gives this old man an advantage over newer generations. The new generations in IBM—which includes many physically older men—can read about these near-death experiences in books, but I lived them. We old men are full of such “life experiences” which are much different from reading about them in history books written by historians who believe truth is better found in emotional detachment. From emotional, deeply ingrained experiences though, old men and women sometimes arrive at better conclusions more quickly because those life experiences help us anticipate tomorrow’s possible effects from today’s cause.

But when I joined IBM in 1980, I was the “new” generation, and I absolutely never forget it.

I worked around men who had more corporate experience in their little finger than I had seen in my entire life. Yet, some of my most memorable experiences taught me that old men can reach wrong conclusions. “We” are fallible. This humbles this old man today, but, even back then, I learned to listen. While, the problems we faced in 1992-93 and 1995-99 were rarely identical to the elders of my time, many were similar, and the way they wrestled a problem to the ground was wisdom I craved. From the individuals I respected, I remember hearing words like perseverance, passion, respect, determination, fairness, service, justice, hard work, equality, family and humility.

This is why I study corporate history. It is, specifically, why I dig diligently into IBM’s history. I am an old man digging into even older men’s thoughts, trials and tribulations. The best of these old men and women constantly pointed out to their new generations that conditions and environments were always different and ever changing; but I have found great similarities in the way Watson Sr., Harvey S. Firestone, Henry Ford, Alfred P. Sloan, Owen D. Young, Gerard Sloan, Dorothy Shaver and others weathered more and greater economic and political storms than most generations. Many times, reading their thoughts as an old man, I feel like a “snot-nosed” kid from the Texas Panhandle again … sitting at the feet of greatness.

One of these industrialists’ basic beliefs was the golden rule. They felt that as it was applicable to individuals, so it should be applied to their corporations. IBM’s history is an alive, squirming, protozoan-like mess of good and bad judgement calls awaiting the revelations of the researcher’s microscopic evaluation. Are conditions today the same? No. Are they similar in many ways? Yes. Does the way the corporation survived the Financial Crisis of 1992‑93 and brought on itself the Cultural Crisis of 1995-99 apply today: Absolutely … if these times are properly researched and documented from multiple perspectives—the views from beneath as well atop the elephant, so to speak.

But when I joined IBM in 1980, I was the “new” generation, and I absolutely never forget it.

I worked around men who had more corporate experience in their little finger than I had seen in my entire life. Yet, some of my most memorable experiences taught me that old men can reach wrong conclusions. “We” are fallible. This humbles this old man today, but, even back then, I learned to listen. While, the problems we faced in 1992-93 and 1995-99 were rarely identical to the elders of my time, many were similar, and the way they wrestled a problem to the ground was wisdom I craved. From the individuals I respected, I remember hearing words like perseverance, passion, respect, determination, fairness, service, justice, hard work, equality, family and humility.

This is why I study corporate history. It is, specifically, why I dig diligently into IBM’s history. I am an old man digging into even older men’s thoughts, trials and tribulations. The best of these old men and women constantly pointed out to their new generations that conditions and environments were always different and ever changing; but I have found great similarities in the way Watson Sr., Harvey S. Firestone, Henry Ford, Alfred P. Sloan, Owen D. Young, Gerard Sloan, Dorothy Shaver and others weathered more and greater economic and political storms than most generations. Many times, reading their thoughts as an old man, I feel like a “snot-nosed” kid from the Texas Panhandle again … sitting at the feet of greatness.

One of these industrialists’ basic beliefs was the golden rule. They felt that as it was applicable to individuals, so it should be applied to their corporations. IBM’s history is an alive, squirming, protozoan-like mess of good and bad judgement calls awaiting the revelations of the researcher’s microscopic evaluation. Are conditions today the same? No. Are they similar in many ways? Yes. Does the way the corporation survived the Financial Crisis of 1992‑93 and brought on itself the Cultural Crisis of 1995-99 apply today: Absolutely … if these times are properly researched and documented from multiple perspectives—the views from beneath as well atop the elephant, so to speak.

IBM: A House Afire with Great People Trying to Save It

In A View from Beneath the Dancing Elephant I use an analogy to describe how almost every IBMer felt going through the Crisis of 1992-93. It describes the difference between those who see a place of business as a house—an economic construct of people, processes and products through which they earn a living; and those who experience a place of business as a home—a social construct of individuals who earn a living together as a work family.

To those considering employment at IBM, you will find the corporation still full of amazing individuals who are top shelf in every way. To join IBM is to join amazing teams, but there is a problem and, as indicated above, the problem is the corner office. Many of these great individuals are fighting the good fight within the upper stories of their corporate home. They smell the danger in the symptomatic, smothering smoke and are stuffing wet towels underneath the doors in an attempt to keep the danger at bay. They see things that are “downright terrible” and try to right them as best they can, but the supportive two-by-fours beneath their feet are crumbling away in an arsonist’s firestorm ignited by finance and fanned by poor human resource practices.

Because our perspectives and our positions within and outside the corporation differ, our rules of engagement are different. I am able to write openly of the danger to the employees in the blaze moving up the structure. This sometimes causes conflict. Sometimes in writing about what is wrong with the corner office, I forget to mention those who are fighting to save the company from within—just as I once did in the mid-and late-90s. I absolutely know that their motives are good, but I fear the fire may not be recognized soon enough.

If it continues to blaze, too many great individuals will lose their jobs either from smoke inhalation or when the entire superstructure collapses. So, I keep yelling “Fire!” because there is a great danger to the corporation, and I always support my position with fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after … well, you get the idea.

To those considering employment at IBM, you will find the corporation still full of amazing individuals who are top shelf in every way. To join IBM is to join amazing teams, but there is a problem and, as indicated above, the problem is the corner office. Many of these great individuals are fighting the good fight within the upper stories of their corporate home. They smell the danger in the symptomatic, smothering smoke and are stuffing wet towels underneath the doors in an attempt to keep the danger at bay. They see things that are “downright terrible” and try to right them as best they can, but the supportive two-by-fours beneath their feet are crumbling away in an arsonist’s firestorm ignited by finance and fanned by poor human resource practices.

Because our perspectives and our positions within and outside the corporation differ, our rules of engagement are different. I am able to write openly of the danger to the employees in the blaze moving up the structure. This sometimes causes conflict. Sometimes in writing about what is wrong with the corner office, I forget to mention those who are fighting to save the company from within—just as I once did in the mid-and late-90s. I absolutely know that their motives are good, but I fear the fire may not be recognized soon enough.

If it continues to blaze, too many great individuals will lose their jobs either from smoke inhalation or when the entire superstructure collapses. So, I keep yelling “Fire!” because there is a great danger to the corporation, and I always support my position with fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after fact after … well, you get the idea.

Hope Is in the Sweet Smell of Success Rooted in the Fertilizing Manure of Failure

|

Although I am now a member of the physically older generation who enjoys reading and writing about the experiences of older and definitely wiser men and women than me, I hope that until the day I die I will remain a member of an ever-learning, ever-renewing generation: men and women who discover fresh thoughts dug from history’s dung heap of failures and who clip new ideas from history’s sweet-smelling, flower-packed fields of success.

In my research I am finding the tallest, brightest and most exquisite flowers of success are deeply rooted in and growing atop the fertilizing manure of past failures. |

The flower of success is many times rooted in failure's manure

|

So, as with individuals—such as me, corporations can learn from their mistakes and be stronger because of them. The golden rule is still a valid rule for business engagement. In this respect, IBM should rediscover one of its past beliefs and reestablish the golden rule as a substantial asset on its balance sheet.

I write articles such as these, remaining forever hopeful that it will. Enjoy these business articles.

Cheers,

- Pete

I write articles such as these, remaining forever hopeful that it will. Enjoy these business articles.

Cheers,

- Pete

[Footnote #1] When James C. Penney published Fifty Years with the Golden Rule in 1950, he wrote that he named his first store the "Golden Rule Store." He shared the following: "For me it [the Golden Rule] had the creative meaning of one of the most fundamental laws that can be expressed in words. We speak of it as having come down to us from the Sermon on the Mount. Of its real origin little is known. We find it specifically stated in the literature of eleven religions."

Mr. Penney and many of the retailers and industrialists of his day believed the Golden Rule was a universal truth.

[Footnote #2] Louis V. Gerstner in Who Says Elephants Can't Dance? fails to mention this quite significant fact. He actually became chief executive officer as it began and left as it was ending.

Mr. Penney and many of the retailers and industrialists of his day believed the Golden Rule was a universal truth.

[Footnote #2] Louis V. Gerstner in Who Says Elephants Can't Dance? fails to mention this quite significant fact. He actually became chief executive officer as it began and left as it was ending.