A Journalist Gets a Tax Story Wrong

Watson’s 1943 Tax “Problem”

- Why Did Watson’s Tax “Problem” Make National News?

- Drew Pearson “Goes All Washington” on Tom Watson

- The Short-Term Effects of the Article on Watson’s Reputation: Calumny

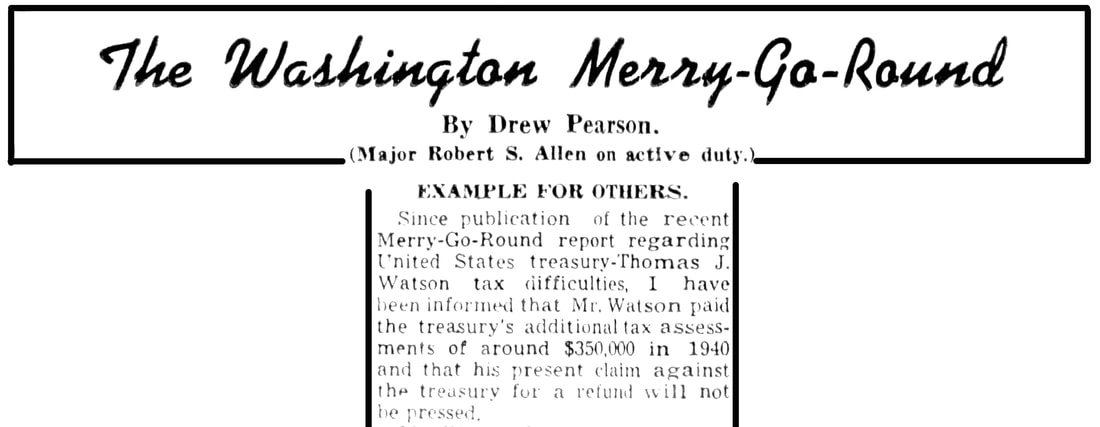

- Drew Pearson Publishes Retraction: Watson is “An Example for Others”

- IBM Business Machines Newspaper Carries the “Rest of the Story”

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

Why Did Watson’s Tax “Problem” Make National News?

|

On December 5, 1942, Tom Watson spoke at an IBM family event in Endicott, New York. He told some 1,400 employees that he did not believe that the high taxes resulting from the war effort would ruin the United States as some were claiming.

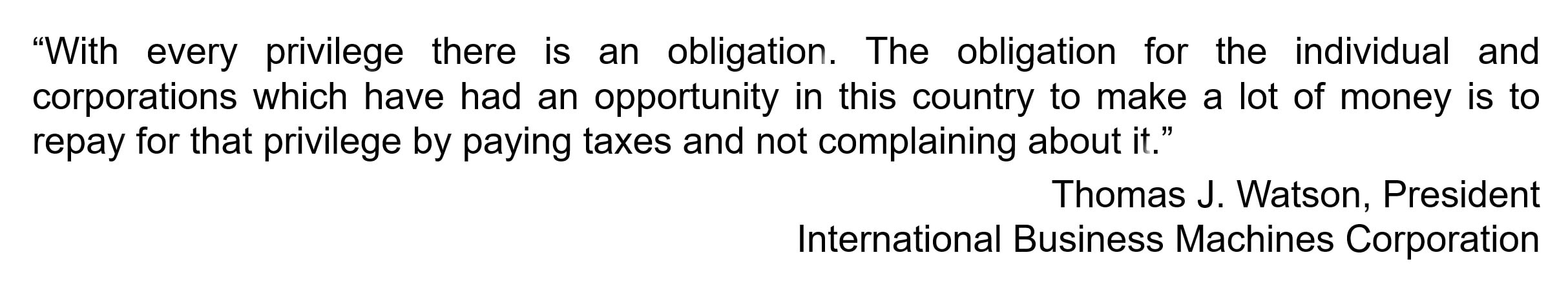

He said that taxes were a just levy on the high wages which the government at that time [World War II] permitted industrial employees to enjoy. He went on to say: “With every privilege there is also an obligation. So, the obligation for the individual and for the corporations which have had an opportunity in this country to make a lot of money is to repay for that privilege, by paying taxes and not complaining about it. … |

"I believe in high wages, and I know we have not hit the top yet. … [high wages] will come about through the genius of the people who invent machine tools for us to work with, and through the ability of men and women who handle those machines … that will give better results.”

The national press picked up on his speech and the following quote appeared in newspapers across the nation from mid-December into the early part of 1943.

Of course, what could possibly make better national news than catching a wealthy, internationally famous business figure—someone not of the “normal” class—in an “apparently” hypocritical statement?

Drew Pearson “Goes All Washington” on Tom Watson in his Syndicated Column

On April 16, 1943, Drew Pearson wrote the following about Tom Watson in his column The Washington Merry-Go-Round:

- Tom Watson is in tax trouble.

- The Treasury is demanding that he pay $350,000 in back taxes.

- Watson filed a petition contesting the tax claim.

- The “problem” arises from claiming a legal tax credit [Treasury ruling 116-A] because he was out of the country for 6 months—maybe.

Included in the article were several subjective, over-the-top, Washingtonian-style, statements such as: He had received more decorations than “most any man in America;” He had filed the tax petition only a “few hours” before the deadline; He “told” stockholders that he was “trying” to sell business machines on all his overseas excursions, and of course Pearson—like so many before and after him—reminded the world of Watson’s acceptance of the German Eagle in 1937. [He “forgot” to mention that Watson was the first of only two who returned their fascist medals in a very public manner.]

|

Surely this nationally-renowned journalist chose his words carefully. Drew Pearson cast an “aura” around the article, one that played on a reader’s emotions to manipulate perceptions based on information not relevant to the subject matter.

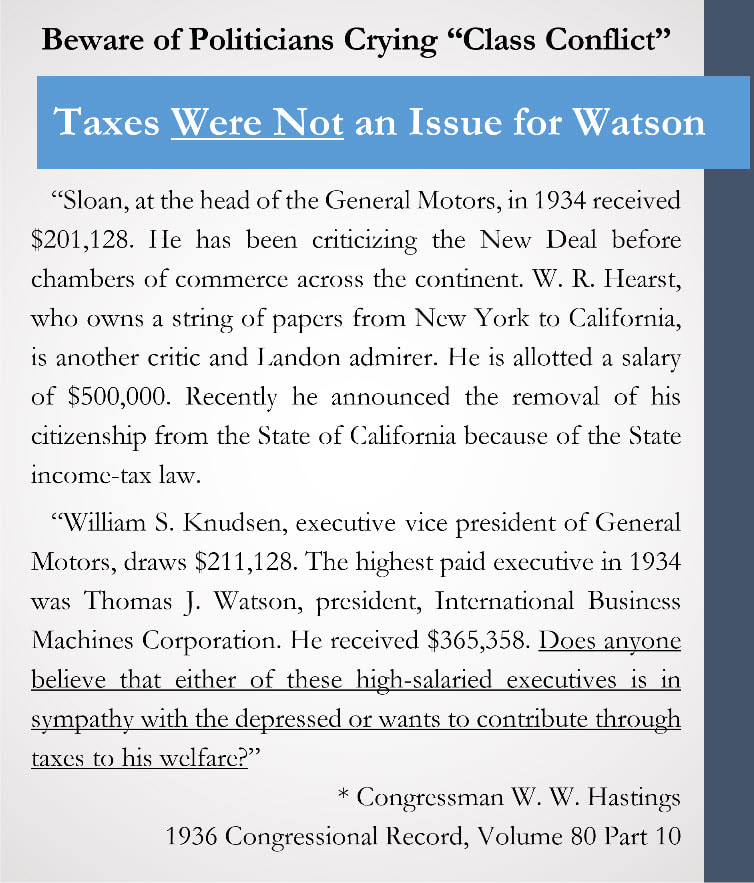

The article played to class conflict and notions of wealth privilege. These are concepts that should seem absurd in a country that advocates a meritocracy-based economic system—where individual effort, talent, and achievement are rewarded rather than inherited wealth, social position or class, or mere existence. If what Pearson wrote had been factual, it would have been quite damaging to Tom Watson’s long-term reputation. The article, though, proved incomplete and inaccurate. But before we get to Pearson’s retraction and our review, let’s consider an interchange between two intelligent, well-placed, political insiders concerning this article about Tom Watson. Henry Morgenthau Jr., the United States Secretary of the Treasury, kept detailed transcripts of his conversations. In this case, Mr. Morgenthau was ensuring that it wasn’t his office that had released personal tax information: an ethical and legal violation if it had. |

Beware of those who pander to "class conflict" for political gain or to incite emotions rather than solid thinking.

|

This conversation took place within a few days of the article’s publication—April 20, 1943. It was between the Secretary of the Treasury and Randolph Paul who, it appears, was a full-time employee of the U.S. Treasury Department.

It probably mirrored the dinner-time conversations of many across the nation.

It probably mirrored the dinner-time conversations of many across the nation.

Calumny: The Short-Term Effect of the Article on Watson’s Reputation

[This interchange has been shortened for clarity without changing the context of the conversation.]

Morgenthau: I’ve been studying the Drew Pearson–Watson matter, and in the file here which they’ve given me it said that you made an inquiry late in March about it.

Paul: Yeah. That’s right. I wanted to know about it because Pearson told me he was going to blast that story, so I asked what the truth was. Pearson got the story from Watson’s secretary.

Morgenthau: You know that as a fact?

Paul: He [Pearson] told me.

Morgenthau: Oh, he did tell you?

Paul: He talked with me about it, and I told him I couldn’t make any statement, and then I checked it in our own files thinking that if there was something untrue about it, I might be able to squash it. But I found that it was perfectly true. Drew has every item, and he told me he got them from this secretary who, incidentally, has made a claim with us.

Morgenthau: Yes.

Paul: We gave Drew no information. It wasn’t necessary.

Morgenthau: I see. That’s all I wanted to know.

Paul: Drew told me every detail. He had everything absolutely right, and he told me he got it from this man.

Morgenthau: Well, I’m sending word to Watson verbally that we here absolutely had nothing to do with it.

Paul: We had absolutely nothing to do with it.

Morgenthau: No.

Paul: The only thing I did when Drew told me he knew about it was to see if there was something about it, we might be able to persuade him not to publish it if it weren’t true.

Morgenthau: Because IBM turned themselves inside out to help us on War Bonds. [This is another story that this author has partially researched. If/when completed, he will provide a link to the article here at a later date.]

Paul: I see. Well, it’s a pretty bad, nasty story on Watson.

Morgenthau: I think on Watson’s, yes, I agree with you.

Paul: Have you seen the file?

Morgenthau: No.

Paul: I went into his correspondence. I was kind of interested. He’d been corresponding with the Duke of Windsor and all kinds of stuff like that. He got an Order of Merit from Hitler. He was playing around there, and I have a notion – I haven’t looked into this; this is a point Pearson hasn’t made. I have a notion that he probably deducted his expense – a lot of those expenses for being over and playing around with Hitler. [Further information is provided on this topic later in this article.]

Morgenthau: Really?

Paul: Well, I – I imagine that’s true, in addition to the fact that he tried to finagle the days he was out of this country. [Further information is provided on this topic later in this article.]

Morgenthau: Well, I think where the man showed very bad judgment was, he paid his tax and then, as I gather, two days before the time expires, he files a refund. And then, on the other hand, he comes out with a public announcement of how he’s taking less salary and all that. [Information on Watson’s salary reductions here]

Paul: That’s right. Well, what I told Wenchel to do was to see that the Bureau denied his claim as promptly as possible … his claim of refund, so that the time would start in which he could bring his suit … let him bring his suit now … he’ll never have the nerve to do it.

Morgenthau: Well, I - I can’t understand these men – I mean, in the first place, a man like Watson getting $700,000 a year. … then he tries to best the Government on his tax. … and then he pays it, and then he goes to work and files a refund which, if it goes before the Tax Appeal Board, that’s all public, isn’t it?

Paul: No, it’s a suit. Yeah, that’s the point [and] the reason why he paid it because he didn’t dare bring a suit at this time during the war. Now by filing a refund claim he has two years in which to bring his suit, two years from the time that the claim is denied. He can’t go before the Board any more. The Board doesn’t have jurisdiction. … But if he had filed an appeal before the Board, it would have become public property. So, to avoid that, he files a refund claim, which is confidential, extending his time to bring his suit. And he thinks, of course, that he can bring the suit after this present war situation is clearer.

Morgenthau: I see. And he has two years in which to do it.

Paul: Yeah. That’s right. I wanted to know about it because Pearson told me he was going to blast that story, so I asked what the truth was. Pearson got the story from Watson’s secretary.

Morgenthau: You know that as a fact?

Paul: He [Pearson] told me.

Morgenthau: Oh, he did tell you?

Paul: He talked with me about it, and I told him I couldn’t make any statement, and then I checked it in our own files thinking that if there was something untrue about it, I might be able to squash it. But I found that it was perfectly true. Drew has every item, and he told me he got them from this secretary who, incidentally, has made a claim with us.

Morgenthau: Yes.

Paul: We gave Drew no information. It wasn’t necessary.

Morgenthau: I see. That’s all I wanted to know.

Paul: Drew told me every detail. He had everything absolutely right, and he told me he got it from this man.

Morgenthau: Well, I’m sending word to Watson verbally that we here absolutely had nothing to do with it.

Paul: We had absolutely nothing to do with it.

Morgenthau: No.

Paul: The only thing I did when Drew told me he knew about it was to see if there was something about it, we might be able to persuade him not to publish it if it weren’t true.

Morgenthau: Because IBM turned themselves inside out to help us on War Bonds. [This is another story that this author has partially researched. If/when completed, he will provide a link to the article here at a later date.]

Paul: I see. Well, it’s a pretty bad, nasty story on Watson.

Morgenthau: I think on Watson’s, yes, I agree with you.

Paul: Have you seen the file?

Morgenthau: No.

Paul: I went into his correspondence. I was kind of interested. He’d been corresponding with the Duke of Windsor and all kinds of stuff like that. He got an Order of Merit from Hitler. He was playing around there, and I have a notion – I haven’t looked into this; this is a point Pearson hasn’t made. I have a notion that he probably deducted his expense – a lot of those expenses for being over and playing around with Hitler. [Further information is provided on this topic later in this article.]

Morgenthau: Really?

Paul: Well, I – I imagine that’s true, in addition to the fact that he tried to finagle the days he was out of this country. [Further information is provided on this topic later in this article.]

Morgenthau: Well, I think where the man showed very bad judgment was, he paid his tax and then, as I gather, two days before the time expires, he files a refund. And then, on the other hand, he comes out with a public announcement of how he’s taking less salary and all that. [Information on Watson’s salary reductions here]

Paul: That’s right. Well, what I told Wenchel to do was to see that the Bureau denied his claim as promptly as possible … his claim of refund, so that the time would start in which he could bring his suit … let him bring his suit now … he’ll never have the nerve to do it.

Morgenthau: Well, I - I can’t understand these men – I mean, in the first place, a man like Watson getting $700,000 a year. … then he tries to best the Government on his tax. … and then he pays it, and then he goes to work and files a refund which, if it goes before the Tax Appeal Board, that’s all public, isn’t it?

Paul: No, it’s a suit. Yeah, that’s the point [and] the reason why he paid it because he didn’t dare bring a suit at this time during the war. Now by filing a refund claim he has two years in which to bring his suit, two years from the time that the claim is denied. He can’t go before the Board any more. The Board doesn’t have jurisdiction. … But if he had filed an appeal before the Board, it would have become public property. So, to avoid that, he files a refund claim, which is confidential, extending his time to bring his suit. And he thinks, of course, that he can bring the suit after this present war situation is clearer.

Morgenthau: I see. And he has two years in which to do it.

|

Paul: Two years from the time that the claim is denied. That’s why I told them to deny the claim promptly so as to start his time running.

Morgenthau: Can you understand these big rich people? Paul: They have marvelous powers of rationalization. [A historical insight—picture provided: Henry Morgenthau Jr. came to trust Tom Watson over the next few years. Consider that four years after this article Morgenthau Jr. asked Watson to be the first chairman of the first national organization of Christians formed to support the United Jewish Appeal (UJA): The National Christian Committee for the United Jewish Appeal. The reason the former Secretary of the Treasury chose Tom Watson was because Tom Watson "epitomized the humanitarian spirit of America."] |

Obviously Henry Morgenthau Jr. came to know Tom Watson well. He asked Watson Sr. to chair the first Christin Committee for the United Jewish Appeal.

|

Drew Pearson Publishes a Retraction: Watson is an “Example for Others”

Drew Pearson’s retraction was timely, simple and straightforward. Watson Sr. had already paid the treasury’s additional tax assessment of $350,000 in 1940—three years prior to Pearson’s original column. Watson’s claim for a refund was filed on advice of tax counsel and was based on precedents that had been set by the tax court which indicated that his original tax returns were correct. Even so, Watson had not pursued the claim.

Drew Pearson’s short retraction carried the following headings around the nation: “Example for Others” and “Example for Big Taxpayers.”

Drew Pearson’s short retraction carried the following headings around the nation: “Example for Others” and “Example for Big Taxpayers.”

A quick search did find one other rather humorous retraction of Drew Pearson’s. When the journalist questioned Henry Ford’s health, the automobile octogenarian—to prove his health—challenged the journalist to a footrace and a retraction was quickly printed; but the search produced no retractions involving such reputation-damaging information as contained in this Watson Sr. article. In fact, when challenged, the journalist appears to have become rather combative in print … even with the President of the United States and his staff. This was how he made his living: stirring up controversies.

Watson must have presented a compelling case … or, humorously, challenged the journalist to a footrace. Watson was just then sneaking up on seventy, and he would have surely been as “light of foot” as the old car magnate.

Watson must have presented a compelling case … or, humorously, challenged the journalist to a footrace. Watson was just then sneaking up on seventy, and he would have surely been as “light of foot” as the old car magnate.

IBM Business Machines Newspaper Carries the “Rest of the Story"

After reprinting Drew Pearson’s April 29th retraction, the IBM Business Machines newspaper of April 30, 1943, Volume 25 Number 16 carried the following information which was written by M. G. Connally, tax counsel for Thomas J. Watson Sr. It contained the information provided Drew Pearson that prompted the journalist to write his retraction.

“The above article refers to a previous item which appeared in the Washington Merry-Go-Round to the effect that Mr. Watson was indebted to the government for additional income tax of $350,000.

“As Tax Counsel for Mr. Watson, I prepared his tax returns in accordance with the laws, rules, and regulations in effect at the time. In 1940, a ruling which I had followed in the preparation of Mr. Watson's returns for 1937, 1938 and 1939 was changed and the change made retroactive, resulting in proposed additional assessments of $335,418.10 for the three years.

“The change in the Treasury Department ruling and the proposed additional assessments were called to Mr. Watson's attention, and he accepted the assessments and paid the amounts due on November 27, 1940. The revenue agent, in the copy of his report furnished the taxpayer, stated that no criticism applied to Mr. Watson or me, as his tax representative, in connection with the additional assessments which resulted merely from the [retroactive] change in ruling.

“I told Mr. Watson that I wanted to keep his case open because I considered the change in ruling incorrect and believed it would be revoked as a result of litigation in cases of other taxpayers, and that the benefit of any such action would automatically apply in his case.

“Mr. Watson stated to me at the time that he would never bring any legal action against the Government for recovery of taxes. Later, when I informed Mr. Watson that in two cases involving similar questions, the United States Tax Court had decided in favor of the taxpayers, he said that nevertheless his position was unchanged, and, on his instructions, the claims for a refund were withdrawn.” [emphasis added]

This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

“Strength of character is the one basic trait which will be found in all people who achieve greatness. When I say character, I do not mean reputation. Character is what you really are and what you know you are. Reputation, on the other hand, is what people think you are, which does not necessarily bear any resemblance to what you really are.”

Tom Watson, First Methodist Episcopal Church, 1932

|

Tom Watson knew who he was. In this instance, he stood up for who he was. He was a man who paid his taxes without complaining. He obviously presented enough facts to convince Drew Pearson—a man who made his living observing and writing about individuals of dubious character, doubtful integrity, and great duplicity of thought. Tom Watson passed Drew Pearson’s test and a retraction was printed.

As far as I can find, this was—at a minimum—a rarity in Pearson’s time as a columnist … if not a lone, solitary occurrence. |

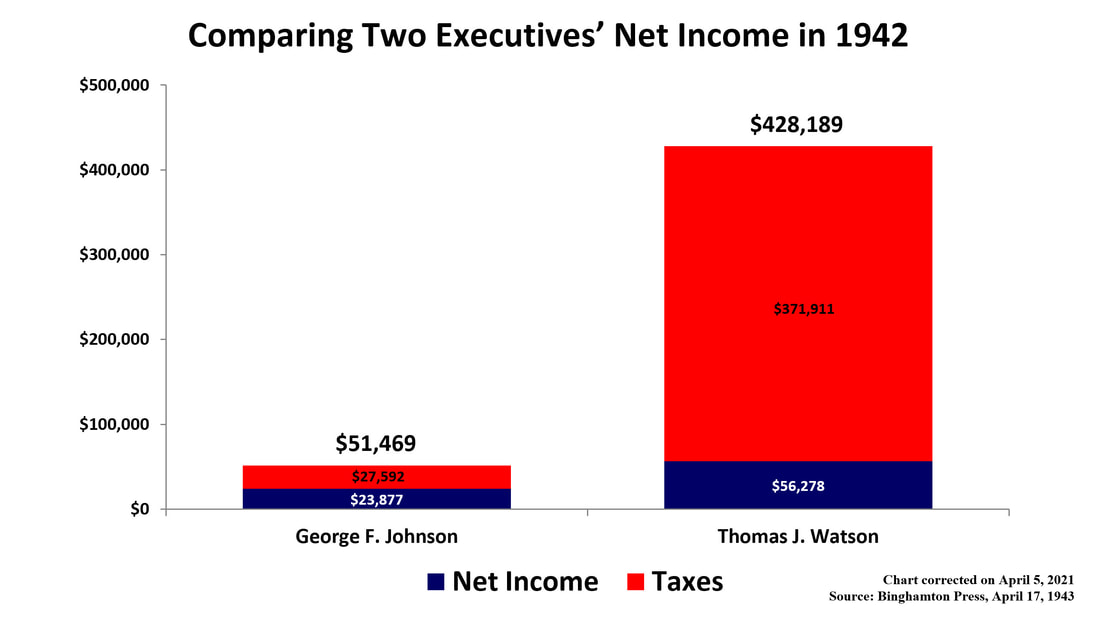

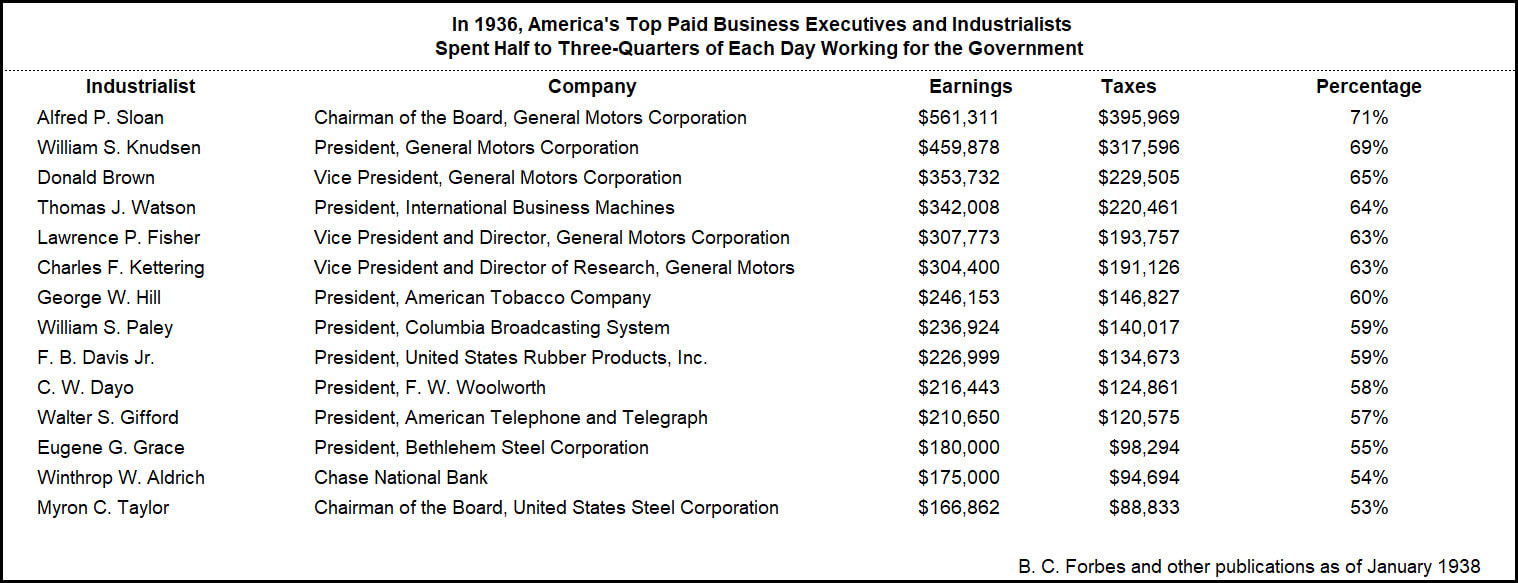

Finally, to put 1937 taxes in perspective, a chart is provided below with data from 1936 showing the taxation rates of the lead industrialists in America. These were the taxes that Tom Watson believed it was their duty to pay: in the range of 50 to 70 percent.

Pearson showed great integrity in printing the retraction.

History should thank him for setting the record straight.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

History should thank him for setting the record straight.

Cheers,

- Peter E.

P.S. If you have further details or find additional information around this story, feel free to contact us. We encourage discussion and interaction, and we enjoy integrating new information as it becomes available. We are always grateful for the donation of pre-1957 IBM newspapers, documents, pamphlets or pictures. They assist greatly in producing factual articles such as this to ensure history remembers Tom Watson correctly.

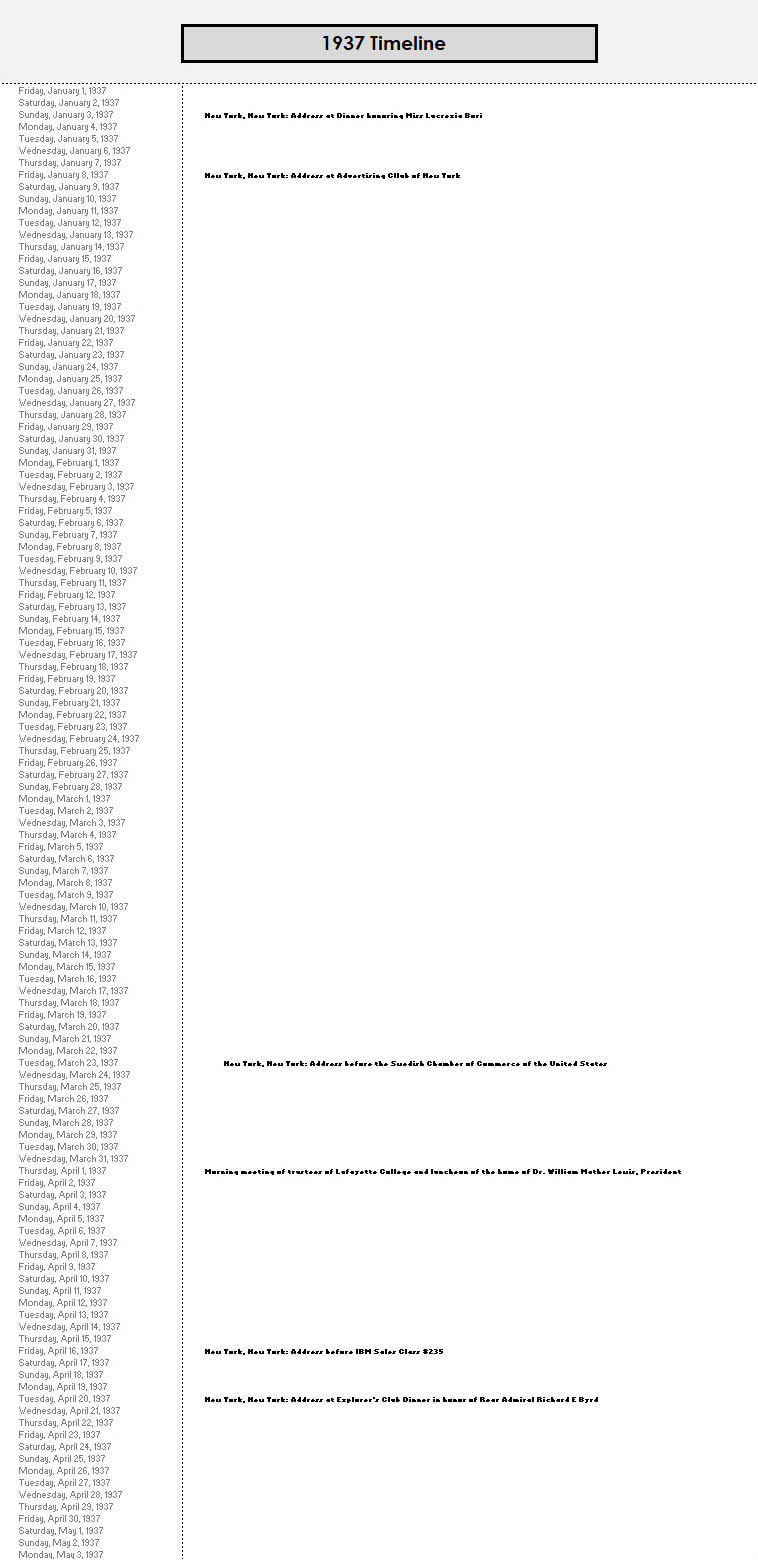

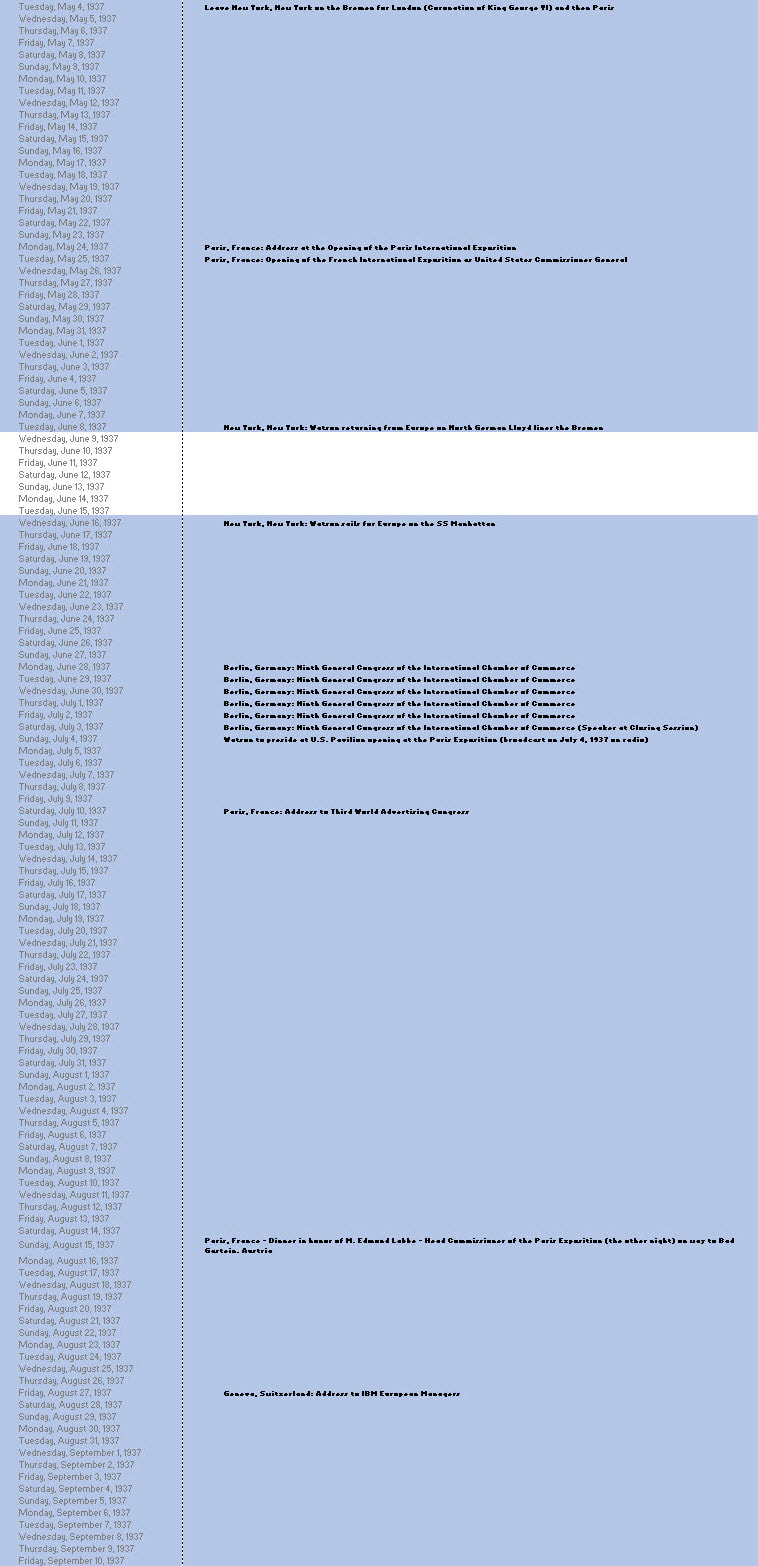

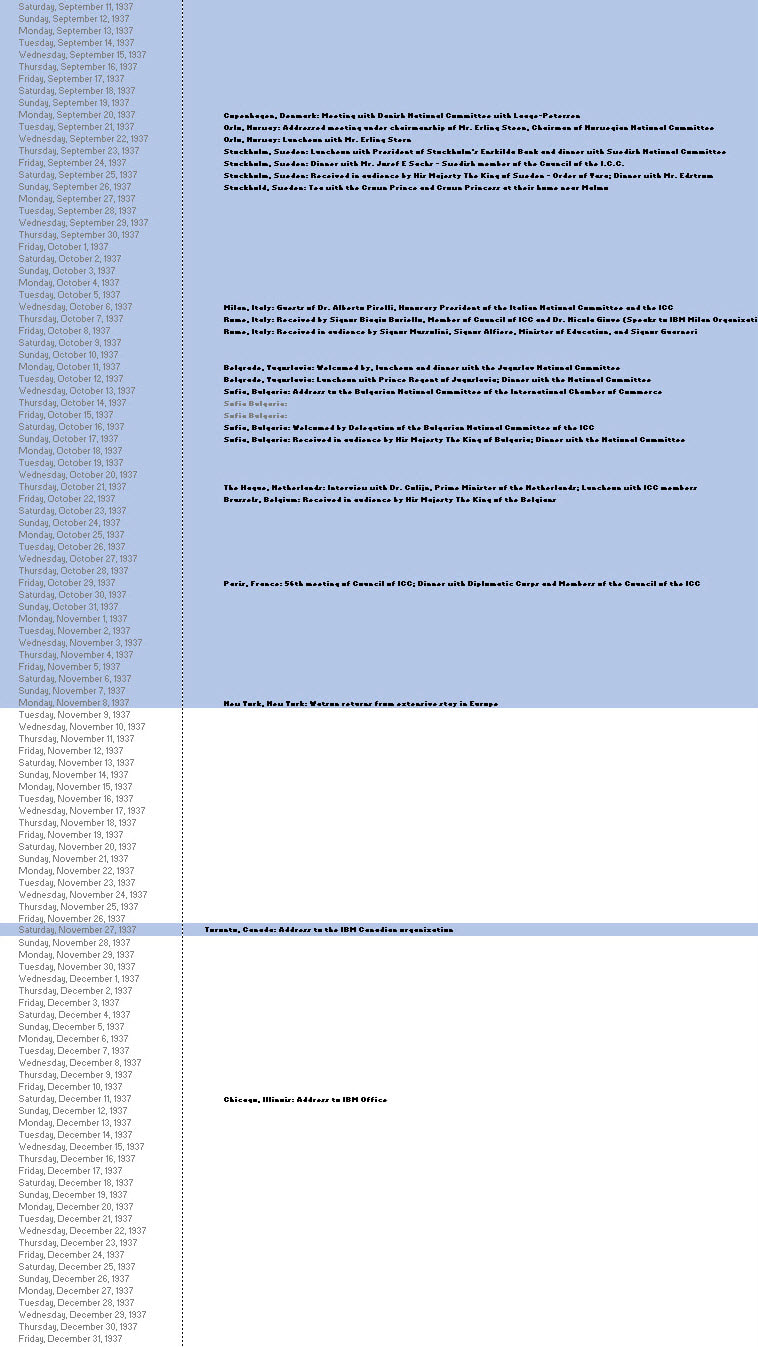

Tom Watson’s 1937 Out-of-Country Itineraries

In the retraction, there was no mention of the six-month out-of-country issue that was highlighted in the original article and mentioned by Randolph Paul. It took this author some time to determine Tom Watson’s out-of-country comings and goings, but it was achievable.

For travel to Europe, it was common practice in the 1937 timeframe to publish the comings and goings of well-known personalities in articles about “Ocean Travelers.” Reporters from major newspapers like The New York Times met arriving and departing passengers on the docks to conduct interviews which were then integrated into current articles.

A review was performed of newspapers to document Tom Watson’s excursions. The following is a conservative estimate of his international travels as any car or train travel to/from Canada or Mexico would be hard to document—especially if Watson only visited the local offices which he did frequently. Here are his 1937 out-of-country excursions.

For travel to Europe, it was common practice in the 1937 timeframe to publish the comings and goings of well-known personalities in articles about “Ocean Travelers.” Reporters from major newspapers like The New York Times met arriving and departing passengers on the docks to conduct interviews which were then integrated into current articles.

A review was performed of newspapers to document Tom Watson’s excursions. The following is a conservative estimate of his international travels as any car or train travel to/from Canada or Mexico would be hard to document—especially if Watson only visited the local offices which he did frequently. Here are his 1937 out-of-country excursions.

|

Thomas J. Watson Sr.’s 1937 European and Canadian Itineraries |

- Out-of-Country Excursions Are in Blue

Using this information, it was easy to document that Tom Watson spent 182 days in Europe on two separate journeys: one itinerary of 36 days and a second itinerary of 146 days. On November 27, 1937, Tom Watson addressed the IBM Canadian organization. There is no doubt that he was physically in Toronto, Canada for at least one day. The speech he delivered on that day is in the book Human Relations published in 1948.

So, make that 183 days—more than half a year. M. G. Connally was right to recommend the six-month overseas tax considerations and filing a claim against the retroactive tax change—to do otherwise could have been considered malpractice. Of course, since Tom Watson never pursued the refund claim, this point is mute and is probably why the actual time out-of-country was omitted from the retraction. It is included here to document he was entitled to the refund that he never took.

|

Thomas J. Watson Sr.: An American Ambassador |

And Tom Watson wasn’t sitting on the Riviera sipping wine, gambling, and enjoying the sun.

Consider these 1937 European itinerary facts:

Consider these 1937 European itinerary facts:

- On his first European trip Tom Watson attended the coronation of King George VI; he attended the French International Exposition in Paris as a United States’ Commissioner General—a Presidential appointment; and he took part in 75th birthday commemoration of Aristide Briand at the University of Paris.

- On his second European trip, he visited thirteen European countries. He was in Berlin long enough to attend and be elected the President of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). After assuming the presidency of the ICC, he journeyed to eight European capitals: Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Rome, Belgrade, Sofia, Brussels, and the Hague. As the head of the ICC, he received three medals—a common European practice, in the name of “World Peace through World Trade.” These three countries, two years later, were both friends and a foe: Sweden and Yugoslavia, and Germany.

At a critical time in 1937, Watson was cementing United States’ relationships with the English, the French, the Belgians, the Swedes, the Norwegians, the Yugoslavians and more … essentially all European countries. In 1938, he was even more active. He served as an ambassador of good will for the American people who after The Great War were loathed to become entangled in yet another European War. He was selling his company, but he was first and foremost America’s Ambassador of Peace. Unfortunately, the dictators and emperors of the world didn’t listen.

So, he eventually became Democracy’s Man O’ War.

So, he eventually became Democracy’s Man O’ War.

Watson’s 1943 Tax “Problem” Timeline

- April 16, 1943 The Washington Merry-Go-Round “In Tax Trouble”

- Tax difficulties arose during 1937.

- Out of the country for 6 months + a few hours.

- April 20, 1943 Morgenthau–Paul conversation

- Morgenthau is confirming that Pearson’s tax information didn’t come from the treasury department.

- Wealth bias shows through—assumed guilty until proven innocent.

- April 29, 1943 The Washington Merry-Go-Round “Example for Big Taxpayers”

- “In fairness to Mr. Watson, I think these additional facts should be known, and that it might be a healthy thing for some other big taxpayers to know about and follow his example.”

- Watson paid the treasury’s additional taxes of $350,000 in 1940 three years before Drew Pearson’s article about “Watson’s tax trouble.”

- Watson is not pressing refund claim.

- This is as close to an open apology as most journalists will make—a retraction and publication of the corrected facts to fix an error that threatened the reputation of a good man. This is how a man of integrity like Pearson ensures he avoids historical calumny, but it is up to future researches to put together the details and print the whole story.

- April 30, 1943 IBM Business Machines Newspaper

- IBM Business Machines reprints the April 29, 1943 retraction by Drew Pearson along with M. G. Connally’s detailed explanation.