THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition: Preface

|

|

Date Published: June 4, 2021

Date Modified: January 6, 2024 |

A preface, which is included in the front matter of a book, is the chance for the author to speak directly to his or her reader about why the book was written, what it's about, and why it's important. In the case of a new edition of a book, it is also where the author will explain what has been changed, added or updated.

This is the Preface for THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition.

This is the Preface for THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition.

Preface to THINK Again!: The Rometty Edition

- What Has Changed

- What Hasn't Changed

- An Observation from Yesterday about Today

- A Personal Response to Personal Attacks

What Has Changed?

|

This preface was added. Charts, graphs, and data points throughout the book have been updated with current information through the end of 2019. A chapter has been added to capture the performance of IBM’s first female chief executive officer, Virginia M. (Ginni) Rometty. This additional chapter focuses on the former chief executive’s key performance metrics such as goodwill, revenue and profit generation, sales and profit productivity, and shareholder risk and returns.

The book examines her acquisition strategy and includes insights into her bet-the-business decision to acquire Red Hat. Arvind Krishna and James M. (Jim) Whitehurst, her successors, will grapple with this 2018 decision just as Rometty struggled with her predecessor’s promise to double earnings per share by 2015 — a commitment she finally, in late 2014, admitted was unattainable. The 2020 coronavirus situation did not impact her results. |

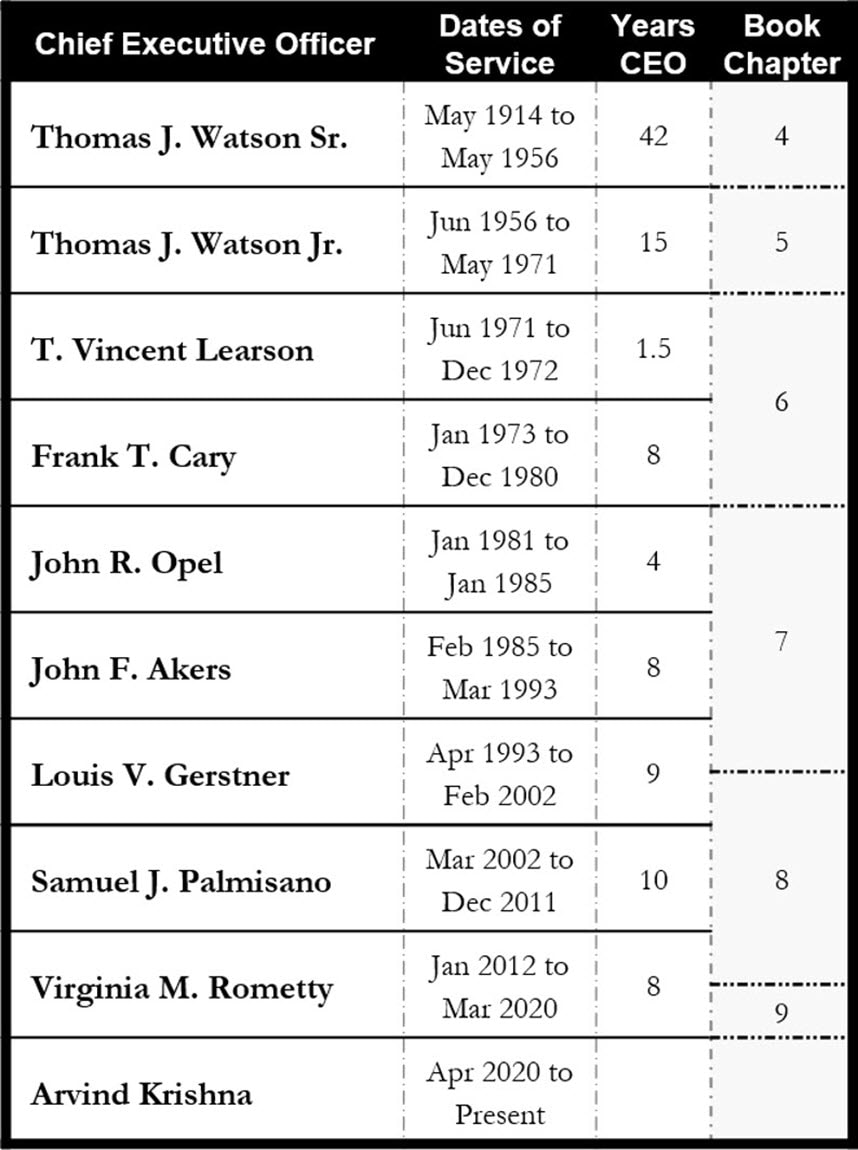

Arvind Krishna is IBM's tenth chief executive.

|

What Hasn’t Changed?

In many ways THINK Again! was prescient. Sales productivity continued its decline. Profit productivity extended its fall. Goodwill grew ever larger, and shareholder risk grew more perilous. The corporation’s falling revenue indicated that customers found fewer reasons to buy, and shareholders who invested in the corporation’s stock suffered significant losses when compared with low-risk mutual funds. Three years of additional data only reinforced the inexorable downward course of these trendlines.

Samuel J. (Sam) Palmisano and Rometty’s disastrous divestiture strategy continued to confirm that John F. Akers’ “Baby Blues” strategy would have doomed the company in the previous century. Louis V. (Lou) Gerstner should be rightfully proud of his “first” and “most important” strategic decision at the time: to keep the corporation together.

But, instead of facing another financial crisis, as the company did in 1992–93, it is ensnared in an ever-worsening cultural crisis. Lou’s financial approach is not what is needed… or even possible. There aren’t any more real estate assets to sell off, pension funds to raid or freeze, 401(k) vesting rights to defer, organizations of the size of the PC or x86-Server Divisions to divest, or high-paying jobs left in the United States or Europe to offshore — all of which propped up this century’s corporate bottom line.

To turn the company around, it will take a person with the internal characteristics highlighted in the last chapter of this book — a chapter that is unchanged. It will take an exceptional person of character to reverse the effects of a two-decades-long cultural travesty and restore employee productivity. As one critic of the first release of this book wrote: It will take a “Jimmy Stewart” type.

Yep, that is the type — not in externals, but internals.

Samuel J. (Sam) Palmisano and Rometty’s disastrous divestiture strategy continued to confirm that John F. Akers’ “Baby Blues” strategy would have doomed the company in the previous century. Louis V. (Lou) Gerstner should be rightfully proud of his “first” and “most important” strategic decision at the time: to keep the corporation together.

But, instead of facing another financial crisis, as the company did in 1992–93, it is ensnared in an ever-worsening cultural crisis. Lou’s financial approach is not what is needed… or even possible. There aren’t any more real estate assets to sell off, pension funds to raid or freeze, 401(k) vesting rights to defer, organizations of the size of the PC or x86-Server Divisions to divest, or high-paying jobs left in the United States or Europe to offshore — all of which propped up this century’s corporate bottom line.

To turn the company around, it will take a person with the internal characteristics highlighted in the last chapter of this book — a chapter that is unchanged. It will take an exceptional person of character to reverse the effects of a two-decades-long cultural travesty and restore employee productivity. As one critic of the first release of this book wrote: It will take a “Jimmy Stewart” type.

Yep, that is the type — not in externals, but internals.

What Isn’t in this Book?

There are no forecasts on how Arvind Krishna (the insider) as the new chief executive officer or Jim Whitehurst (the outsider) as the new president will perform.

These two leaders deserve time to formulate their strategies, but they can learn from their predecessors’ successes and failures: remove incompetent executives — especially when they are at the highest levels of the corporation; reject strategies that prioritize short-term results over the long-term health of the business; never stoke market expectations; quit strategic roadmaps that inspire employees to call themselves roadkill; never manage to a stock price; and, when action is necessary, act quickly and decisively.

They should share power. The history of General Electric (G.E.) contains the example of two excellent leaders who shared power elegantly: Owen D. Young and Gerard Swope.

These two leaders deserve time to formulate their strategies, but they can learn from their predecessors’ successes and failures: remove incompetent executives — especially when they are at the highest levels of the corporation; reject strategies that prioritize short-term results over the long-term health of the business; never stoke market expectations; quit strategic roadmaps that inspire employees to call themselves roadkill; never manage to a stock price; and, when action is necessary, act quickly and decisively.

They should share power. The history of General Electric (G.E.) contains the example of two excellent leaders who shared power elegantly: Owen D. Young and Gerard Swope.

An Observation from Yesterday about Tomorrow

For the first time since Frank T. Cary and John R. Opel, the company has two chief executives who may share power for an extended period of time. [See Footnote #1] There is an example from American corporate history that these two executives should emulate.

A similar change in power structure took place at G.E. in the midst of the Recession of 1920–21 when Charles A. Coffin — the only chief executive officer the workers had ever known — orchestrated his retirement. The author of Swope of G.E. wrote that the nervous system of the company quivered “like the strings of Paderewski’s piano” as the men “fretted impotently” about what Gerard Swope as president and Owen D. Young as chief executive officer “might do to them and their jobs.” [See Footnote #2]

When Owen Young was asked about how he and Gerard Swope would work together, he gave a simple answer: “One of us will be the captain and the other navigator.” Swope, as president, responded, “I will do all the work — I like it.” Theirs was a synergistic match, and G.E. righted itself under their leadership. They turned the downward trajectory of the corporation’s earnings upward and, after more than two decades sharing the top positions at G.E., they contributed many outstanding, leadership principles that were woven into the fabric of the world’s largest corporations — even IBM.

Unfortunately, IBM’s cultural nervous system has been desensitized to the edge of impotency by two decades of constant attacks on job security: “right-sizing” initiated by Lou Gerstner, quarterly “resource actions” dictated by Sam Palmisano, and incessant “workload rebalancing” imposed by Ginni Rometty. These processes carried different labels, but all of them were euphemisms for a single word: layoffs. These executives shared one consistent notion: in the pursuit of ever higher earnings per share, job security was toast. The result has been falling sales and profit productivity.

The board of directors must ensure that Krishna and Whitehurst are as successful as Swope and Young. If these two new chief executives delay, do not move decisively, or fail to find a way to negate each other’s weaknesses and amplify each other’s strengths, the board of directors must act without hesitation. They must act, not in the best interest of the shareholders, but in the common interest of the corporation’s stakeholders: its customers, employees, stockholders, and the societies they coinhabit.

This stakeholder ecosystem has always been a major theme of this book. In order to maximize the earnings of any single investor, all the corporate investors — stakeholders — must coexist in a supportive, self-sustaining ecosystem. Daniel Quinn Mills, professor emeritus at Harvard Business School, highlights this in his Foreword [available here]:

The author tells us that shareholder wealth can only be maximized in the long term by balancing the interests of the major stakeholders of a firm. Thus, what is generally treated as an either/or choice — shareholder or stakeholder value maximization — is, in reality, a necessary combination in which both objectives are achieved and complement one another.

This is a striking conclusion.

A similar change in power structure took place at G.E. in the midst of the Recession of 1920–21 when Charles A. Coffin — the only chief executive officer the workers had ever known — orchestrated his retirement. The author of Swope of G.E. wrote that the nervous system of the company quivered “like the strings of Paderewski’s piano” as the men “fretted impotently” about what Gerard Swope as president and Owen D. Young as chief executive officer “might do to them and their jobs.” [See Footnote #2]

When Owen Young was asked about how he and Gerard Swope would work together, he gave a simple answer: “One of us will be the captain and the other navigator.” Swope, as president, responded, “I will do all the work — I like it.” Theirs was a synergistic match, and G.E. righted itself under their leadership. They turned the downward trajectory of the corporation’s earnings upward and, after more than two decades sharing the top positions at G.E., they contributed many outstanding, leadership principles that were woven into the fabric of the world’s largest corporations — even IBM.

Unfortunately, IBM’s cultural nervous system has been desensitized to the edge of impotency by two decades of constant attacks on job security: “right-sizing” initiated by Lou Gerstner, quarterly “resource actions” dictated by Sam Palmisano, and incessant “workload rebalancing” imposed by Ginni Rometty. These processes carried different labels, but all of them were euphemisms for a single word: layoffs. These executives shared one consistent notion: in the pursuit of ever higher earnings per share, job security was toast. The result has been falling sales and profit productivity.

The board of directors must ensure that Krishna and Whitehurst are as successful as Swope and Young. If these two new chief executives delay, do not move decisively, or fail to find a way to negate each other’s weaknesses and amplify each other’s strengths, the board of directors must act without hesitation. They must act, not in the best interest of the shareholders, but in the common interest of the corporation’s stakeholders: its customers, employees, stockholders, and the societies they coinhabit.

This stakeholder ecosystem has always been a major theme of this book. In order to maximize the earnings of any single investor, all the corporate investors — stakeholders — must coexist in a supportive, self-sustaining ecosystem. Daniel Quinn Mills, professor emeritus at Harvard Business School, highlights this in his Foreword [available here]:

The author tells us that shareholder wealth can only be maximized in the long term by balancing the interests of the major stakeholders of a firm. Thus, what is generally treated as an either/or choice — shareholder or stakeholder value maximization — is, in reality, a necessary combination in which both objectives are achieved and complement one another.

This is a striking conclusion.

A Personal Response to Personal Attacks

Ida M. Tarbell, one of America’s greatest journalists, in her autobiography responded to those who typecast her into the role of muckraker. She wrote of the muckraking profession — one that she helped define:

The truth of the matter was that the muckraking school was stupid. It had lost the passion for facts in a passion for subscriptions.

Ida M. Tarbell, All in the Day’s Work

If this great researcher responded to criticism to ensure that history understood her motivations… may I impose on you for a moment?

The company’s executive team would like its employees, business partners and journalists to ignore the facts in this book. They wave off these facts as the product of a “disgruntled employee.” I have seen this typecasting generalization used so often that a response seems appropriate.

I served in the military from 1971 to 1974. I worked for several large and small companies before IBM. I put my heart and soul into every organization until it was time to move to the next act in my life, but my long-term passion — my deepest heartfelt passion — still burns for the twentieth-century IBM. It was this leadership that was determined to build a company to last forever. They built a great company on three simple, memorable beliefs: respect for the individual, service to the customer, and the pursuit of excellence. We old-timers referred to these foundational beliefs as Respect, Service, and Excellence.

I believe that the young at heart as well as those young in years will find hope in the early history of IBM. We lived and worked in a business environment that they too seem to desire but are unable to find. They are not that different from the men and women I worked alongside… or those who came before us… or those who will come after us.

Ultimately, we are more alike than we are different.

Cheers,

- Pete

The company’s executive team would like its employees, business partners and journalists to ignore the facts in this book. They wave off these facts as the product of a “disgruntled employee.” I have seen this typecasting generalization used so often that a response seems appropriate.

I served in the military from 1971 to 1974. I worked for several large and small companies before IBM. I put my heart and soul into every organization until it was time to move to the next act in my life, but my long-term passion — my deepest heartfelt passion — still burns for the twentieth-century IBM. It was this leadership that was determined to build a company to last forever. They built a great company on three simple, memorable beliefs: respect for the individual, service to the customer, and the pursuit of excellence. We old-timers referred to these foundational beliefs as Respect, Service, and Excellence.

I believe that the young at heart as well as those young in years will find hope in the early history of IBM. We lived and worked in a business environment that they too seem to desire but are unable to find. They are not that different from the men and women I worked alongside… or those who came before us… or those who will come after us.

Ultimately, we are more alike than we are different.

Cheers,

- Pete

[Footnote #1] Frank Cary and John Opel shared the top positions for six years (1974 to 1980). John Opel and John Akers shared the top positions for two years (1983 to 1985). Lou Gerstner and Sam Palmisano shared the positions for less than two years (July 2000 to March 2002). Sam Palmisano and Ginni Rometty never shared power.

[Footnote #2] Gerard Swope and Owen Young took over General Electric in 1922 when it had, in two short years, lost almost 50% of its customers. During the Recession of 1920–21, the company’s orders dropped from $318,000,000 in 1920 to $179,000,000 in 1921. It was $45,000,000 in debt — equivalent to two years of net income. Plants were running at a fraction of their capacity. The corporation was in dire straits.

[Footnote #2] Gerard Swope and Owen Young took over General Electric in 1922 when it had, in two short years, lost almost 50% of its customers. During the Recession of 1920–21, the company’s orders dropped from $318,000,000 in 1920 to $179,000,000 in 1921. It was $45,000,000 in debt — equivalent to two years of net income. Plants were running at a fraction of their capacity. The corporation was in dire straits.