A Review of David Loth's "Swope of G.E."

|

|

Date Published: June 24, 2021

Date Modified: January 6, 2024 |

The author, David Loth, does an excellent job in this work emphasizing the strengths of a chief executive without pulling any punches on an executive's weaknesses and their effects on the men close to him.

His analysis is one of the best I have read of any biographer documenting the dual sided nature of a chief executive who is driven to succeed. In many ways he articulated in this work an old saying popularized by Herbert Hoover: “If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.”

His analysis is one of the best I have read of any biographer documenting the dual sided nature of a chief executive who is driven to succeed. In many ways he articulated in this work an old saying popularized by Herbert Hoover: “If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.”

A Review of "Swope of General Electric (G.E.)" by David Loth

- Reviews of the Day: 1958

- Overview of "Swope of G.E."

- This Author’s Thoughts and Perceptions

Reviews of the Day: 1958

|

"Swope’s story fits well into the classic mold of successful executive biography. … But it also has an important social dimension rarely found in stories of business success. Swope became General Electric’s president in 1922. …

"While many of his colleagues were seeking economic recovery through exhortations of confidence, he was despairing of President Hoover’s inaction and advocating a control scheme comparable to NRA [National Recovery Act]. … Although mindful that his identification with the New Deal might cost General Electric some business, Swope considered it his duty to speak up for social insurance and the National Labor Board. … "One wonders if the “Swopes” of today can reach the corporate top … if there are many men like Gerard Swope in American Business today." |

Armand W. Reeder, Between Book Ends, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 1, 1958

Overview of "Swope of G.E."

The author, David Loth, does an excellent job in this work emphasizing the strengths of a chief executive without pulling any punches on his weaknesses and their effects on the men close to him. His analysis was one of the best I have read of any biographer documenting the dual sided nature of a chief executive who is driven to succeed. In many ways he articulated in this work an old saying popularized by Herbert Hoover: “If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.”

A chief executive driven by a concern for his employees and business stability is the toughest of taskmasters. To such an individual, failure is not an option because too many employees’ livelihoods depend on success. In a wonderful observation about the diversity of views in Swope’s followers, the author observes that there were different types of men who surfaced in his interviews:

"There are those who hate to be driven, and those who glory in it, bragging about what a tough guy they work for. Depending upon which type was talking about him, Swope was a ruthless machine with no human compassion or a great leader of men.

"But unlike many severe taskmasters, he never ranted or swore or abused people."

Gerard Swope, though, might be forgiven if he did use a few choice words of motivation, because he took over during some tough times for General Electric.

A chief executive driven by a concern for his employees and business stability is the toughest of taskmasters. To such an individual, failure is not an option because too many employees’ livelihoods depend on success. In a wonderful observation about the diversity of views in Swope’s followers, the author observes that there were different types of men who surfaced in his interviews:

"There are those who hate to be driven, and those who glory in it, bragging about what a tough guy they work for. Depending upon which type was talking about him, Swope was a ruthless machine with no human compassion or a great leader of men.

"But unlike many severe taskmasters, he never ranted or swore or abused people."

Gerard Swope, though, might be forgiven if he did use a few choice words of motivation, because he took over during some tough times for General Electric.

|

Swope Takes Charge During Tough Times

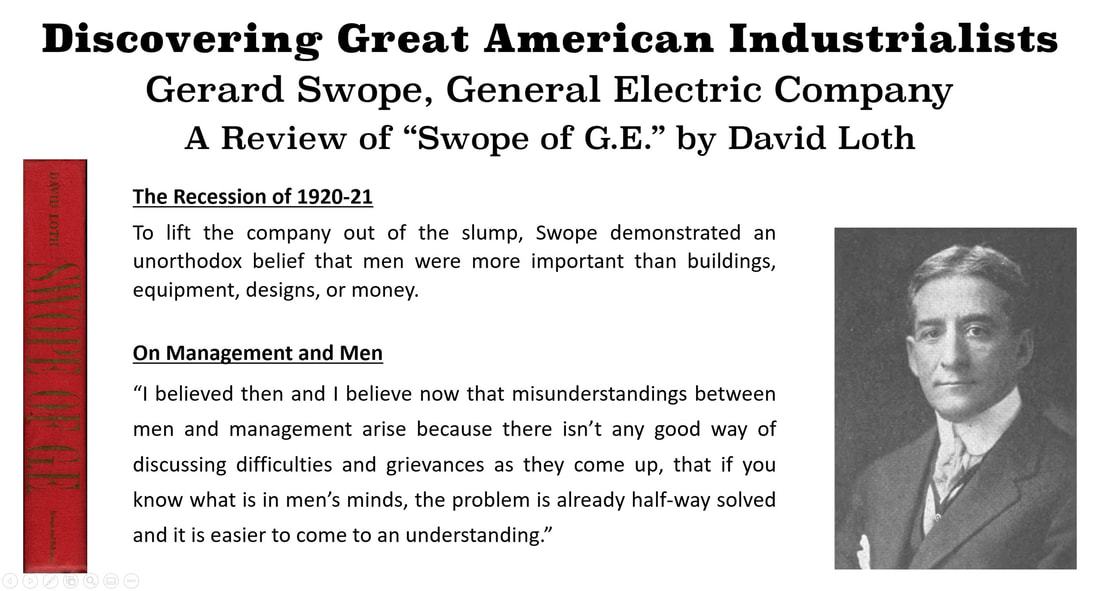

Gerard Swope took over General Electric in 1922 when it had, in two short years, lost almost 50% of its customers. During the Recession of 1920-21, the company’s orders dropped from $318,000,000 in 1920 to $179,000,000 in 1921. It was $45,000,000 in debt—equivalent to two years of net income. Plants were running at a fraction of their capacity. The corporation was in dire straits.

Many in the country felt that the recession was a proof point that “corporate growth had passed the point of maximum efficiency” and that medium-sized companies could out-produce and undersell the “clumsier giants.” Swope had other ideas. He brought the company back with a belief in the importance of the common worker within the giant organization, but he had to stay focused. Here is one of the quotes from Gerard Swope as he took over G.E. from its first chief executive, Charles A. Coffin: "Management today defines its own responsibilities. It depends on the personal factor of the president … It depends on whether he [or she] is selfish and narrow, or broad and has a sense of stewardship." [emphasis added] Swope Was about Stewardship

|

Mr. Swope worked most of his adult life demonstrating his sense of “stewardship.” Swope implemented corporate-wide unemployment insurance at GE and advocated transferable, industry-wide, unemployment insurance during the Great Depression.

With his Swope Plan he encouraged cross-country, industry-wide safety nets for employees during tough economic times. When he realized that industry was failing to live up to what he considered one of its major responsibilities to employees, he advised FDR in the specifics of implementing the government’s social security safety net. He felt it was a needed step to stabilize the economy by restoring consumer confidence.

As I read the book, I had similar thoughts as Armand W. Reeder, of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, who, as captured above, summed up his review of Swope of GE: "One wonders if the “Swopes” of today can reach the corporate top, and furthermore if there are many men like Gerard Swope in American Business today."

As I read the book, I had similar thoughts as Armand W. Reeder, of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, who, as captured above, summed up his review of Swope of GE: "One wonders if the “Swopes” of today can reach the corporate top, and furthermore if there are many men like Gerard Swope in American Business today."

Of course, in 1958 Tom Watson Jr. of IBM was just getting started wasn't he?

The exceptions do make an impression, don't they?

The exceptions do make an impression, don't they?

This Author's Thoughts and Perceptions

Swope Was an Industrialist and American Citizen

The book is an amazing read and I would place it in the top five biographies I have read of American industrialists. It not only revealed the leadership skills of a great industrialist, but his concerns for his fellow man and the society in which he lived.

In most books, I invariably find one chapter that is a standout. In this work I found three: A Managerial Revolution, Men and Motives, and Secrets of Management. This still doesn’t quite capture the quality of the material, though, as these were the superlatives of chapters which were all outstanding. The others such as “The New Deal” would have been highlighted in most any other work, as insights flowed from every chapter.

The book provides wonderful insights into the Recession of 1920-21 and into the Great Depression and shows that many influential businessmen supported FDR and his New Deal. Swope in his “Swope Plan” proposed that industry should live up to its obligations to its employees, but he was pragmatic. This proved impossible under Hoover, and when the chance presented itself to take his ideas directly to President Roosevelt, he stood tall.

The President during a one-on-one luncheon asked Swope for his advice on what sound economic systems should look like for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance and disability benefits. Swope was ready. He did not need any notes. He had been presenting his “Swope Plan” so often that the facts were memorized. Furthermore, because pension plans and unemployment insurance were already in operation at General Electric, he spoke about practical implementations arrived at through failed and successful experimentations.

He outlined his plan to the Commander in Chief, and as he did, he observed “the President’s enthusiasm mounting” until “he caught the fire of the idea.”

Swope Concerned Himself with Facts

Gerard Swope, like Tom Watson Sr., was a man who studied facts. So many times, we believe that chief executives just “shoot from the hip.” Swope, again like Watson, had teams within G.E. that gathered information and data for him. At one time when he was comparing business size with stability, he had his team pull together statistics on the survival rates of corporations. When the figures came to him, he commented, “Twenty million companies have come into being, and almost the same number have disappeared.”

From the study, it was determined that, at the time, there were only twenty companies older than General Electric which traced its roots back to the General Edison Company founded in 1878. The major companies were Du Pont, 1802; Western Union, 1851; Waltham Watch, 1854; Wanamaker, 1861; Pullman 1867; Western Electric, 1869, and Singer Sewing Machine, 1873.

The book is an amazing read and I would place it in the top five biographies I have read of American industrialists. It not only revealed the leadership skills of a great industrialist, but his concerns for his fellow man and the society in which he lived.

In most books, I invariably find one chapter that is a standout. In this work I found three: A Managerial Revolution, Men and Motives, and Secrets of Management. This still doesn’t quite capture the quality of the material, though, as these were the superlatives of chapters which were all outstanding. The others such as “The New Deal” would have been highlighted in most any other work, as insights flowed from every chapter.

The book provides wonderful insights into the Recession of 1920-21 and into the Great Depression and shows that many influential businessmen supported FDR and his New Deal. Swope in his “Swope Plan” proposed that industry should live up to its obligations to its employees, but he was pragmatic. This proved impossible under Hoover, and when the chance presented itself to take his ideas directly to President Roosevelt, he stood tall.

The President during a one-on-one luncheon asked Swope for his advice on what sound economic systems should look like for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance and disability benefits. Swope was ready. He did not need any notes. He had been presenting his “Swope Plan” so often that the facts were memorized. Furthermore, because pension plans and unemployment insurance were already in operation at General Electric, he spoke about practical implementations arrived at through failed and successful experimentations.

He outlined his plan to the Commander in Chief, and as he did, he observed “the President’s enthusiasm mounting” until “he caught the fire of the idea.”

Swope Concerned Himself with Facts

Gerard Swope, like Tom Watson Sr., was a man who studied facts. So many times, we believe that chief executives just “shoot from the hip.” Swope, again like Watson, had teams within G.E. that gathered information and data for him. At one time when he was comparing business size with stability, he had his team pull together statistics on the survival rates of corporations. When the figures came to him, he commented, “Twenty million companies have come into being, and almost the same number have disappeared.”

From the study, it was determined that, at the time, there were only twenty companies older than General Electric which traced its roots back to the General Edison Company founded in 1878. The major companies were Du Pont, 1802; Western Union, 1851; Waltham Watch, 1854; Wanamaker, 1861; Pullman 1867; Western Electric, 1869, and Singer Sewing Machine, 1873.

Boards of Directors Need to Step Up

The more things change, the more they remain the same. Even today, I wonder if the type of chief executives we need in authority are making it to the top of America’s greatest corporations or if those that are there—now both men and women—are of the highest character type: those who aren’t selfish and narrow but broad in their outlook with a sense of stewardship.

Maybe it will take a Recession/Depression to weed out the weak and instruct the willing in the right way to run a business over the longer term, just like the Recession of 1920-21 did in this instance to General Electric and other American brand names such as General Motors, Firestone, IBM and Goodyear. The failures of some of America’s greatest brands in the 21st Century like Sears, Roebuck & Company would suggest corporations have been negligent in how they promote, install and then fail to fire poor leadership.

The twenty-first century board of directors have been negligent in their responsibilities, not so much to their shareholders but to the businesses they ultimately should be serving. They are failing to remove poor chief executives with fundamental character flaws.

IBM is an example of one such corporation. The sales and profit productivities of its employees have been in a two-decade decline, yet its board fails to act. There is only one ending for such companies if they don’t reverse the falling enthusiasm, engagement and passion of their employees: failure.

Just as Gerard Swope engaged his employees during difficult times, IBM needs a leader who can once again engage its workforce.

Maybe it will take a Recession/Depression to weed out the weak and instruct the willing in the right way to run a business over the longer term, just like the Recession of 1920-21 did in this instance to General Electric and other American brand names such as General Motors, Firestone, IBM and Goodyear. The failures of some of America’s greatest brands in the 21st Century like Sears, Roebuck & Company would suggest corporations have been negligent in how they promote, install and then fail to fire poor leadership.

The twenty-first century board of directors have been negligent in their responsibilities, not so much to their shareholders but to the businesses they ultimately should be serving. They are failing to remove poor chief executives with fundamental character flaws.

IBM is an example of one such corporation. The sales and profit productivities of its employees have been in a two-decade decline, yet its board fails to act. There is only one ending for such companies if they don’t reverse the falling enthusiasm, engagement and passion of their employees: failure.

Just as Gerard Swope engaged his employees during difficult times, IBM needs a leader who can once again engage its workforce.

A Desire to Read more about Swope's Fellow Industrialists

|

The one critique of the book is the tendency of the author to make Gerard Swope, not just an outstanding individual in his own right, but an individual standing alone when there were many standing with him. Although it is dramatic writing to make a single individual strong enough to overcome all odds, it is more realistic and ultimately closer to reality that there were many who were like-minded and supported each other during the Great Depression.

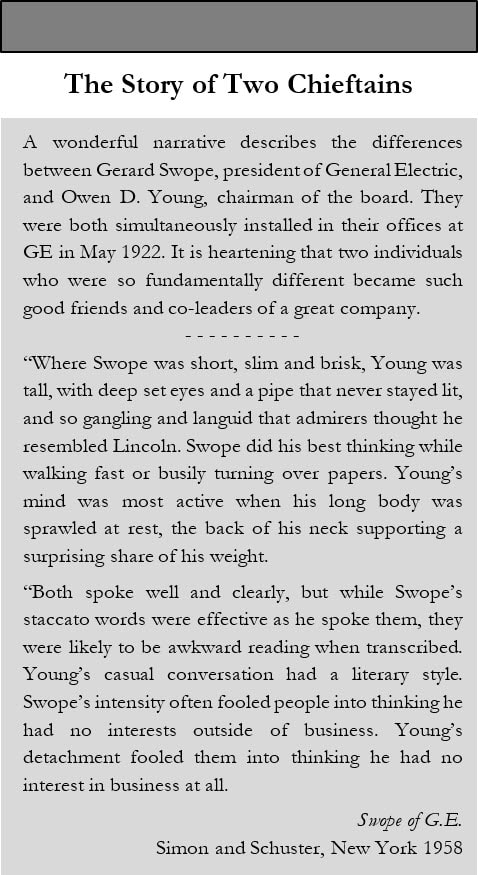

I have found this same tendency within myself and other IBM employees. We personalize Watson Sr.’s leadership to something like “the one and only” who created a family atmosphere. Research is documenting that these industrialists did not stand alone. There was a consolidated effort by many business leaders who knew and supported each other to ensure their corporations lived up to their obligations to all stakeholders: customers, employees, shareholders and society. It is a lengthy list of those who worked within and outside of their corporations to instill an awareness of the obligations of business. Men and women such as Edward A. Filene of Wm. Filene’s Sons & Company, Thomas J. Watson Sr. of IBM, Owen D. Young of General Electric, Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck & Company, Elbert H. Gary of U.S. Steel, Harvey S. Firestone of Firestone Tire Company, John H. Patterson of NCR Corporation, George Eastman of Eastman Kodak, and Dorothy Shaver of Lord & Taylor.

The list includes one of Gerard Swope’s classmates at MIT: Alfred P. Sloan Jr. |

Thoughts: On Autobiographies

Reading this biography drove home one of the fallacies of autobiographies like Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? by Lou Gerstner. Individuals will make observations to an independent author they might rarely say directly to a chief executive. Reading such an honest and open biography as Swope of GE exposed some of the flaws in autobiographies: chief executives are people too and may never admit or even be cognizant of their shortcomings.

Lou, of course, did not write such perspectives in his self-evaluation, and there are 10's of thousands of IBMers who are suffering today in retirement because of his pension decisions of 1995 and 1999.

They will never forgive him and have only been given a voice through A View from Beneath the Dancing Elephant.

Lou, of course, did not write such perspectives in his self-evaluation, and there are 10's of thousands of IBMers who are suffering today in retirement because of his pension decisions of 1995 and 1999.

They will never forgive him and have only been given a voice through A View from Beneath the Dancing Elephant.

Perspective: Amazing Point of Similarity between General Electric and IBM

When Gerard Swope gave up his G.E. presidency in 1938 to Charles Wilson, his successor took the immediate step that Watson Jr. took at IBM eighteen years later in 1956: they both moved from monarchial, centralized organizations to decentralized operations. Swope initially protested this decentralization, but finally agreed that he had delegated power and abided by “Electric Charlie’s” decision.

The following is the last paragraph from Swope of GE and implies that decentralization was the right course:

One day recently Wilson was explaining that the great significance of his predecessor in American life was that he “introduced the new concepts of management into industry which made it click.” Someone remarked that General Electric had its most spectacular expansion in Wilson’s own presidency. The big man nodded. “But it was on Gerard Swope’s foundation,” he said. “Wilson couldn’t have done it.”

So, it was for Watson Jr. standing on Watson Sr.’s foundation: “Junior” couldn’t have done it alone.

It took two men in both corporations to achieve what was achieved.

They were all men of their times.

The following is the last paragraph from Swope of GE and implies that decentralization was the right course:

One day recently Wilson was explaining that the great significance of his predecessor in American life was that he “introduced the new concepts of management into industry which made it click.” Someone remarked that General Electric had its most spectacular expansion in Wilson’s own presidency. The big man nodded. “But it was on Gerard Swope’s foundation,” he said. “Wilson couldn’t have done it.”

So, it was for Watson Jr. standing on Watson Sr.’s foundation: “Junior” couldn’t have done it alone.

It took two men in both corporations to achieve what was achieved.

They were all men of their times.

“We are like dwarfs sitting on the shoulders of giants. We see more … not because our sight is superior or because we are taller than they, but because they raise us up, and by their great stature add to ours.”

[Footnote #1] Wikipedia says that Swope served as President of General Electric through 1945. This biography says the following: "Swope delivered it [their resignations] for both of them [Swope and Young] on his seventy-second birthday." Swope was born on December 1, 1872. So although there may have been a delay in processing, Swope [and Young] would have considered himself done on the day he handed in his resignation for the second time: December 1, 1944.