A Review of Lincoln Steffen's "Autobiography"

|

|

Date Published: July 6, 2021

Date Modified: June 30, 2024 |

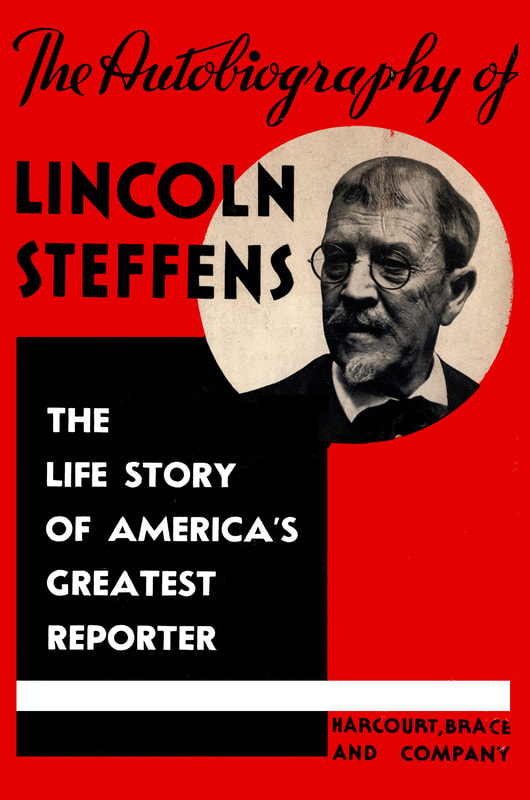

First impressions are sometimes difficult to shake. When this book arrived and before I even opened it, I thought: “That cover seems pretty brazen.” In the boldest of types, across the front cover was, “The Life Story of America’s Greatest Reporter.” Although I try to not judge a book by its cover, by the time I read the last page of this autobiography my closing thought was, “Greatest? Maybe, in his own mind!” "Stef" worked across the desk from two of the greatest: Ida M. Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker! Talk about challenging company for comparisons.

I would hate to disagree with Carl Sandburg who wrote on the inside cover, “A human wizard wrote this book. It hasn’t a garrulous page.” Unfortunately, I know multiple synonyms for garrulous to describe this work: talkative, chatty, loquacious, repetitive and effusive.

Nothing can take away from what Lincoln Steffens accomplished in his exposure of grit, grime, and crime in early American local and state politics … except his own ego that is contained within this book, but lacks containment.

Most reviewers of the day disagree with this evaluation of mine … that's why I include them.

I would hate to disagree with Carl Sandburg who wrote on the inside cover, “A human wizard wrote this book. It hasn’t a garrulous page.” Unfortunately, I know multiple synonyms for garrulous to describe this work: talkative, chatty, loquacious, repetitive and effusive.

Nothing can take away from what Lincoln Steffens accomplished in his exposure of grit, grime, and crime in early American local and state politics … except his own ego that is contained within this book, but lacks containment.

Most reviewers of the day disagree with this evaluation of mine … that's why I include them.

Peter E. Greulich, 2021

A Review of Lincoln Steffens' Autobiography

- Reviews of the Day: March through December 1931

- Insights from Lincoln Steffens' Autobiography

- This Author’s Thoughts on Lincoln Steffens' Autobiography

Reviews of the Day: March through December 1931

|

“It is pleasant to find after reading his just issued autobiography that one feels that the admiration and perhaps [my] early adoration was not misplaced. Steffens exposed crime—he was the muckraker par excellence, and yet he always at the same time could enter somewhat into the criminal’s psychology as well. He pointed to the social rather than the individual implications [emphasis added].

“I have read somewhere that there is a Talmudical tradition that when a Jew was executed in ancient Jewish times, the rabbi would chant: ‘Forgive us the murder that we have committed.’ You felt something of the same spirit in Steffens.” David Schwartz, The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, 1931

“Lincoln Steffens, born in California made himself one of the two or three greatest reporters in the world more than thirty years ago. He was the first popular writer to expose political corruption and graft in American cities and elsewhere. … I have read no book in years which is so stimulating. Everybody who is in the least concerned with the future of himself, his children, or his country ought to read it [emphasis added].”

Frank Parker Stockbridge, Today and Tomorrow, 1931

|

“The book is more than a brilliant treatise on government. It is the sensitively and often beautifully written record of an honest mind at work on the crazy world in which we live. One has a suspicion that some of his latest conclusions are wrong. But they are never dull [emphasis added].”

Dexter M. Keezer, Ex Libris, 1931

“In his portrayal of crime and criminals the public mind was greatly influenced to believe that there is no integrity nor patriotism left among the common people. It is to be hoped that Mr. Lincoln Steffens will live long enough to realize that the fundamental principles upon which our nation has been founded are in the main correct: that not all new things are good and not all old things are bad; that the criminal is the exception and not the rule, and that the great majority of our people are law-abiding, patriotic, useful citizens.”

Mining Congress Journal, Steffens Autobiography, 1931

Insights of Lincoln Steffens from his Autobiography

“In short, what I got out of my second period in Wall Street was this perception: that everything I looked into in organized society was really a dictatorship, in this sense, that it was an organization of the privileged for the control of privileges, of the sources of privilege, and of the thoughts and acts of the unprivileged.”

Lincoln Steffens, "Chapter 32: Wall Street Again"

|

“My book [The Boston 1915 Plan] was a disappointment to everybody, and my theory is that it had no relation to any kind of thinking that was being done at that time. It was an attempt to muckrake our American ideals—not our bad conduct but our virtues—as a sign and as a continuing cause of our evils.

“In a country and in an era in which (1) good people believed that bad people caused the evil which good people, if elected to power, would cure, and (2) the more scientific minds held that bad economics caused both the evils and the ideals, there was no public, there were no publishers, for my thesis that there were two sources of evil and that one of the two was our ideals.” Lincoln Steffens, "Chapter 35: The Muck I Raked in Boston"

|

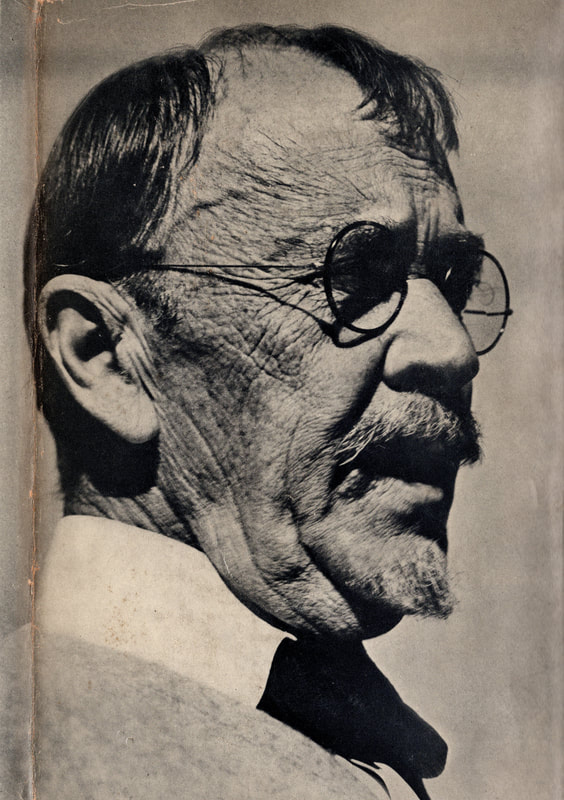

Picture from back cover of Autobiography

|

“I could see that one trouble with our education was that it did not teach us what was not known, not enough of the unsolved problems of the sciences, of the arts, and of life. It did not aim, apparently, to make us keen with educated, intelligent curiosity about the unknown, not eager to do the undone; it taught most of us only what was known.

“It gave us positive knowledge when there was no certain knowledge, and worst of all, when we did not particularly want it. We were not curious as students, and we are not curious enough now as men and women. It seemed to me, as I thought and talked it over with others, that curiosity was the beginning and the end of education, and that if one could arouse that in the minds of college students, they might reverse their relations with their teachers. The students would be asking questions, not the professors; the students would be learning instead of the teacher teaching.

“No systematic efforts were made in the colleges I knew, to stimulate first the wish to know, before handing out required knowledge. If this were done, if the students could be sent into the classroom eager to know all about some subject, then the professor’s pleasant business would be to offer carefully, not with any certainty, the little uncertain knowledge he has; then to point off at the unsolved problems in that science, with cautious statements of the assumptions and theories with which the researchers were working; and finally, when the students are ready for more, for the unknown, to drill them in the methods of modern research.”

“It gave us positive knowledge when there was no certain knowledge, and worst of all, when we did not particularly want it. We were not curious as students, and we are not curious enough now as men and women. It seemed to me, as I thought and talked it over with others, that curiosity was the beginning and the end of education, and that if one could arouse that in the minds of college students, they might reverse their relations with their teachers. The students would be asking questions, not the professors; the students would be learning instead of the teacher teaching.

“No systematic efforts were made in the colleges I knew, to stimulate first the wish to know, before handing out required knowledge. If this were done, if the students could be sent into the classroom eager to know all about some subject, then the professor’s pleasant business would be to offer carefully, not with any certainty, the little uncertain knowledge he has; then to point off at the unsolved problems in that science, with cautious statements of the assumptions and theories with which the researchers were working; and finally, when the students are ready for more, for the unknown, to drill them in the methods of modern research.”

Lincoln Steffens, "Part II: Experimenting with Philanthropy and Education"

“What they [the Bolsheviks] were doing is another question, and it is important. Lenin and his successors, the Bolsheviks, were sweeping away a culture, an organization of society, which they named capitalism and hated as a failure which threw up a few rich, many poor, and all grasping, cowardly, mean.

“Their theory was that human nature can be, if not changed, then so cultivated and selected by economic conditions that the more desirable parts will survive, the undesirable instincts be discouraged. They were founding on the revolution, on the cleared bottom of society, a new system without any incentives to or possibilities of riches and poverty, graft, war, injustice, tyranny.

“They were abolishing private property and making labor the owner and governor of all things and all men.”

“Their theory was that human nature can be, if not changed, then so cultivated and selected by economic conditions that the more desirable parts will survive, the undesirable instincts be discouraged. They were founding on the revolution, on the cleared bottom of society, a new system without any incentives to or possibilities of riches and poverty, graft, war, injustice, tyranny.

“They were abolishing private property and making labor the owner and governor of all things and all men.”

Lincoln Steffens, "Chapter XX: Mussolini"

A Personal Thought from this Author on Revolution

I am not sure I could ever get to where Steffens arrived at: to believe in revolution—or any type of war—as a path to final peace. Required for the defense of peace? Absolutely!

Ida M. Tarbell wrote of her findings when studying the French disposition to revolution:

"The heaviest blow to my self-confidence … was my loss of faith in revolution as a divine weapon. Not since I discovered the world not to have been made in six days of twenty-four hours each, had I been so intellectually and spiritually upset. I had held a revolution as a noble and sacred instrument, destroying evil and leaving men free to be wise and good and just.

"Now it seemed to me not something that men used, but something that used men for its own mysterious end and left behind the same relative proportion of good and evil as it started with."

As you will read, I agree with Miss Tarbell not Lincoln Steffens.

With that insight, now for my book review.

Ida M. Tarbell wrote of her findings when studying the French disposition to revolution:

"The heaviest blow to my self-confidence … was my loss of faith in revolution as a divine weapon. Not since I discovered the world not to have been made in six days of twenty-four hours each, had I been so intellectually and spiritually upset. I had held a revolution as a noble and sacred instrument, destroying evil and leaving men free to be wise and good and just.

"Now it seemed to me not something that men used, but something that used men for its own mysterious end and left behind the same relative proportion of good and evil as it started with."

As you will read, I agree with Miss Tarbell not Lincoln Steffens.

With that insight, now for my book review.

This Author’s Thoughts on Lincoln Steffens' Autobiography

"Human reason has little influence on one who believes he is inspired"

Ida M. Tarbell, All in the Day’s Work

This quote of Ida M. Tarbell’s was not said of Lincoln Steffens, but it seems applicable to this work of his. My feeling from reading the reviews was that few of the authors actually made it to the end of the book. They were lovers of the early “Muckraker Steffens” and ignored what he had become by the end of his book and life: “Propagandist Steffens.” Unlike many of his reviewers who loved, “The Early Life of Lincoln Steffens,” I skipped the early life and went directly to his joining the staff of McClure's Magazine. Even then, it was hard getting though this erudite, overly-wordy, overly-pompous, 884-page tome.

As the reader gets deeper into the book, that which S.S. McClures feared might happen to Lincoln Steffens actually comes to pass:

As the reader gets deeper into the book, that which S.S. McClures feared might happen to Lincoln Steffens actually comes to pass:

|

"I [Lincoln Steffens] felt that his [McClure’s] concern was for our journalism. He feared that, as a doctrinaire, I would degenerate from a reporter into a propagandist … I was not afraid myself. I liked to change my mind.

"There was a risk in theorizing. I had witnessed, close up, the fatal, comic effect upon professors and students of hypotheses which had become unconscious convictions." By the end of the book Lincoln Steffens had a closed mind. He was a propagandist … almost to an extreme that he could not recognize within himself. Anyone that dared disagree with him was not his equal. His journey was a journey of truth that he saw being achieved in both the Bolshevik Russia and the factories of Henry Ford. Only propaganda can unify those two economic theories of life, right to property and work, and Lincoln Steffens tries to reconcile them. Of the reviews, the one that best reached the description of my feelings about the book was that “Lincoln Steffens tells us what he told great men, not what they told him.” |

Unlike Mark Sullivan, Steffens is constantly in the way of a better story. And, unfortunately, he tells all these men pretty much the same thing: the “system” is the problem. Of course, any individual would love to be excused from their unethical behavior by “the system made me do it. I am just an honest cog in a dishonest wheel.”

It is an autobiography, but Mr. Steffens ego always presents itself as saying the correct thing—and it being accepted by every recipient, reaches unbelievable proportions. One wonders how many of these powerful bosses of the day, after talking to him—after he believed he had so “enlightened” them—turned to their secretaries and said, “What a pompous, intellectual ass!”

"Intelligentsia are intellectuals who form an artistic, social, or political vanguard or elite."

It is an autobiography, but Mr. Steffens ego always presents itself as saying the correct thing—and it being accepted by every recipient, reaches unbelievable proportions. One wonders how many of these powerful bosses of the day, after talking to him—after he believed he had so “enlightened” them—turned to their secretaries and said, “What a pompous, intellectual ass!”

"Intelligentsia are intellectuals who form an artistic, social, or political vanguard or elite."

Merriam-Webster

|

The word intelligentsia comes to mind reading this autobiography—specifically, an elitist. Having risen from the “working ranks,” I do not use this term with any positive connotations. Words like isolation, elitism, detached from reality, and unworkable ideas, come to mind. By my definition, their heads are usually so far in the clouds, that they can’t see the realities of the men and women who toil the soil at their feet: in this case, even peasants would like to own the land they work.

This may seem harsh and actually off the mark as you start this book. Steffens seems to always write about the people and the common man, but it is when you get to the last few chapters and Lincoln Steffens describes his time in Russia during the revolution—describing the wandering masses in misery, and compares it to the United States with its wealth—maybe not evenly distributed but producing affordable cars: "It seemed to me, fresh from Europe where nothing new is doing, that Henry Ford, the industrial leader in a land of industrial pioneering, was a prophet without words, a reformer without politics, a legislator, statesman—a radical. I understood why the Bolshevik leaders of Russia admired, coveted, studied him. "He was a labor leader, for example, with no sentiment at all about the workers, handling labor as he did raw material, he learned by experience to stand for high wages. … It [his car] was good enough for common use; it had to be cheap enough for everybody to have one. That is what “use” meant to this man whose head was working like a red’s—a Bolshevik’s [emphasis added]." |

I tried finding any comment by Henry Ford on these few pages from the autobiography, but he appears to have been silent. Mr. Steffens is not mentioned in the three books published by Henry Ford in conjunction with Samuel Crowther. Ford’s last book, Moving Forward was published in the same year as this autobiography, so timing played into that. Mr. Steffens even writes about Henry Ford’s conflict with his shareholders which I covered separately in my own research prior to reading this book.

Lincoln Steffens gets the details right, but to make it “Russian and Revolutionary” was a leap, it appears, that only Mr. Steffens could take.

"He [Henry Ford] bought them [the shareholders] out. … he did what his followers will all have to do some day; he abolished his stockholders to remove an obstacle to progress. He still had to pile up profits into a surplus, but this was to protect himself against the banks, which were after him as they are after all industry and business. Also he needed, in this stage of our civilization, a surplus as an experimental fund to finance, himself, the big changes he saw ahead. … This was Russian and Revolutionary [emphasis added]."

One way to explain the acceptance of this book in 1931 is to consider the timing. It was on the downward side of the Great Depression with a trough that was still two years away. Disillusionment with capitalism was growing. Anarchy, socialism, communism and fascism were all being proposed as better alternative systems than capitalism as an economic institution or democracy as a political institution.

Ultimately, Mr. Steffens seems to see every moral, political and economic conflict resolved through revolution. I am glad he was wrong, or else we would not have the great country we have today—so many countries have tried revolution since 1931. Although, he appears to have had a friendship with Owen D. Young, CEO of General Electric he only mentions the man in passing—running one of the great industrialist institutions of his day. Mr. Steffens never develops this relationship, and only writes flatteringly that, “big business was absorbing science, the scientific attitude and the scientific method. Cocksureness, unconscious ignorance, were giving way to experiment.”

This is a theme that Ida M. Tarbell picked up in one of her books. It is also important to note that Ida M. Tarbell had a much different observation of American Industry and its evolution through a “silent” revolution:

Lincoln Steffens gets the details right, but to make it “Russian and Revolutionary” was a leap, it appears, that only Mr. Steffens could take.

"He [Henry Ford] bought them [the shareholders] out. … he did what his followers will all have to do some day; he abolished his stockholders to remove an obstacle to progress. He still had to pile up profits into a surplus, but this was to protect himself against the banks, which were after him as they are after all industry and business. Also he needed, in this stage of our civilization, a surplus as an experimental fund to finance, himself, the big changes he saw ahead. … This was Russian and Revolutionary [emphasis added]."

One way to explain the acceptance of this book in 1931 is to consider the timing. It was on the downward side of the Great Depression with a trough that was still two years away. Disillusionment with capitalism was growing. Anarchy, socialism, communism and fascism were all being proposed as better alternative systems than capitalism as an economic institution or democracy as a political institution.

Ultimately, Mr. Steffens seems to see every moral, political and economic conflict resolved through revolution. I am glad he was wrong, or else we would not have the great country we have today—so many countries have tried revolution since 1931. Although, he appears to have had a friendship with Owen D. Young, CEO of General Electric he only mentions the man in passing—running one of the great industrialist institutions of his day. Mr. Steffens never develops this relationship, and only writes flatteringly that, “big business was absorbing science, the scientific attitude and the scientific method. Cocksureness, unconscious ignorance, were giving way to experiment.”

This is a theme that Ida M. Tarbell picked up in one of her books. It is also important to note that Ida M. Tarbell had a much different observation of American Industry and its evolution through a “silent” revolution:

However great the lack of efficiency and justice in American industry, it is undergoing a silent revolution. This revolution is centered in industrial management. Back of it lies a belated realization that the responsibility for the weaknesses and unrest of our industrial life does not rest with the American workman, but with his employer.

The stability of this new movement lies in the fact that management is summoning to its aid great forces which it has hitherto believed to have little or no part in its function. It has summoned science, and growing numbers of American business managers are holding that there is no task which men perform which should not be studied scientifically.

The new management employs not only science but humanity, and by humanity I do not mean merely or chiefly sympathy but rather a larger thing, the recognition that all men, regardless of race, origin or experience, have powers for greater things than has been believed. I doubt, indeed, if there has been any economic and social gain in the last fifty years which equals· this growing conviction of the Powers of the Common Man.

Ida M. Tarbell, New Ideals in Business

The individuals and businesses that Miss Tarbell wrote about, Lincoln Steffens either never mentions or only mentions in passing with no insights offered [Edward A. Filene is one exception with a chapter dedicated to their interactions in Boston. Mr. Filene, though, never mentions Lincoln Steffens in his work that was released the same year: [Successful Living in the Machine Age.].

Her work was undertaken after Mr. Steffens left the American. Maybe he should have stayed centered on gathering more complete facts, rather than turning to dogma and propaganda. Here is what he wrote of himself when he expressed his theories to a group of businessmen traveling Europe:

"I could not … point out the facts and the views to these commercial-political tourists and let them take or leave what they saw. I had to mix it all in. A propagandist, I tried to force them to get it or acknowledge that they were what Sinclair Lewis called them later, much later—Babbitts [a person—especially a business or professional man—who conforms unthinkingly to prevailing middle-class standards]."

Let’s close out this review with one of the observations that Lincoln Steffens made late in his life about his “death”—made during the year that this autobiography was released and five years before his physical death. [See Footnote #1]

Her work was undertaken after Mr. Steffens left the American. Maybe he should have stayed centered on gathering more complete facts, rather than turning to dogma and propaganda. Here is what he wrote of himself when he expressed his theories to a group of businessmen traveling Europe:

"I could not … point out the facts and the views to these commercial-political tourists and let them take or leave what they saw. I had to mix it all in. A propagandist, I tried to force them to get it or acknowledge that they were what Sinclair Lewis called them later, much later—Babbitts [a person—especially a business or professional man—who conforms unthinkingly to prevailing middle-class standards]."

Let’s close out this review with one of the observations that Lincoln Steffens made late in his life about his “death”—made during the year that this autobiography was released and five years before his physical death. [See Footnote #1]

"I have been practicing the art of dying for ten years. My death has been gradual, but it has finally come. Dying is an art like painting or writing. When I decided to die, ten years ago, I gave up all my responsibilities. I arranged my affairs in proper order. I wrote my will. Today I am as free as only a dead man can be. I don’t have to write a line for money.

"My opinions are my own. I can sit back on the fence and watch the waves with a smile. … Now that I am dead I can voice honest opinions. … Only dead persons and fools speak the truth. I am a radical—as red as anyone. … I believe that America will eventually turn and follow the ideas that are now being carried out in Soviet Russia [by this time under Stalin, not Lenin]. What chance would I have to say that if I were alive?"

When I first read this I laughed and thought, “Sounds like my retirement.” History, though, does assign responsibility—even to the dead and retired—for their words and actions. Followers, of course, can and will misinterpret their words or fail to understand their intent, but that becomes evident with time and open discussion in free-speech, listening-is-an-obligation, societies. In the Christian world, one only has to think of the effect of propaganda on true spirituality: In the Inquisition anyone who didn’t think alike was evil and must be tortured to change their beliefs or killed if they wouldn't.

Sometimes in reading this work of Lincoln Steffens, I believed, as Stannard Baker wrote, he was truly bright but caught a messianic complex cold late in life. Deluded messiahs speak without fear of the effect of their words after their "deaths." False messiahs are propagandists for mindless causes – soothsayers rather than effective tellers of truths.

"Stef," always has a cute turn of a phrase, a very unique outlook on life, but he was as dogmatic—as propagandistic—as any false messiah. And he had his followers and worshipers—of which, I am neither. Now that I am retired I can also voice the honest opinions of … the dead … the fool … and the retired.

I haven’t given up my responsibilities. I’ll hang onto those until I physically die because …

Truths lacking deep roots in responsibility, usually aren’t truths …

They’re weeds.

Cheers,

- Pete

Postscript: So, I have read the autobiographies of the “Lives of the Three Mucketeers.” I would rate Ida M. Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker on par with each other for maintaining a standard of excellence in their writings. Miss Tarbell would be significantly higher than Stannard Baker, but both are top performers. Lincoln Steffens autobiography was laborious to read, wandering, and offered little to nothing beyond the writings of his fellow two muckrakers.

"My opinions are my own. I can sit back on the fence and watch the waves with a smile. … Now that I am dead I can voice honest opinions. … Only dead persons and fools speak the truth. I am a radical—as red as anyone. … I believe that America will eventually turn and follow the ideas that are now being carried out in Soviet Russia [by this time under Stalin, not Lenin]. What chance would I have to say that if I were alive?"

When I first read this I laughed and thought, “Sounds like my retirement.” History, though, does assign responsibility—even to the dead and retired—for their words and actions. Followers, of course, can and will misinterpret their words or fail to understand their intent, but that becomes evident with time and open discussion in free-speech, listening-is-an-obligation, societies. In the Christian world, one only has to think of the effect of propaganda on true spirituality: In the Inquisition anyone who didn’t think alike was evil and must be tortured to change their beliefs or killed if they wouldn't.

Sometimes in reading this work of Lincoln Steffens, I believed, as Stannard Baker wrote, he was truly bright but caught a messianic complex cold late in life. Deluded messiahs speak without fear of the effect of their words after their "deaths." False messiahs are propagandists for mindless causes – soothsayers rather than effective tellers of truths.

"Stef," always has a cute turn of a phrase, a very unique outlook on life, but he was as dogmatic—as propagandistic—as any false messiah. And he had his followers and worshipers—of which, I am neither. Now that I am retired I can also voice the honest opinions of … the dead … the fool … and the retired.

I haven’t given up my responsibilities. I’ll hang onto those until I physically die because …

Truths lacking deep roots in responsibility, usually aren’t truths …

They’re weeds.

Cheers,

- Pete

Postscript: So, I have read the autobiographies of the “Lives of the Three Mucketeers.” I would rate Ida M. Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker on par with each other for maintaining a standard of excellence in their writings. Miss Tarbell would be significantly higher than Stannard Baker, but both are top performers. Lincoln Steffens autobiography was laborious to read, wandering, and offered little to nothing beyond the writings of his fellow two muckrakers.

[Footnote #1] It appears that the edition of Lincoln Steffens autobiography I read was a one-volume edition sold at half the price of the two-volume edition. It was released sometime in late (October) 1931. This later, one-volume edition was supposedly printed with no omission of pictures or any change in text by Harcourt, Brace and Company.